Чарльз Дарвин

Life and Letters of Charles Darwin — Volume 2

My dear Gray, yours most sincerely, C. DARWIN.

P.S. — Several clergymen go far with me. Rev. L. Jenyns, a very good naturalist. Henslow will go a very little way with me, and is not shocked with me. He has just been visiting me.

[With regard to the attitude of the more liberal representatives of the Church, the following letter (already referred to) from Charles Kingsley is of interest:]

C. KINGSLEY TO CHARLES DARWIN. Eversley Rectory, Winchfield, November 18th, 1859.

Dear Sir,

I have to thank you for the unexpected honour of your book. That the Naturalist whom, of all naturalists living, I most wish to know and to learn from, should have sent a scientist like me his book, encourages me at least to observe more carefully, and perhaps more slowly.

I am so poorly (in brain), that I fear I cannot read your book just now as I ought. All I have seen of it AWES me; both with the heap of facts and the prestige of your name, and also with the clear intuition, that if you be right, I must give up much that I have believed and written.

In that I care little. Let God be true, and every man a liar! Let us know what IS, and, as old Socrates has it, epesthai to logo — follow up the villainous shifty fox of an argument, into whatsoever unexpected bogs and brakes he may lead us, if we do but run into him at last.

From two common superstitions, at least, I shall be free while judging of your books: —

1. I have long since, from watching the crossing of domesticated animals and plants, learnt to disbelieve the dogma of the permanence of species.

2. I have gradually learnt to see that it is just as noble a conception of Deity, to believe that he created primal forms capable of self development into all forms needful pro tempore and pro loco, as to believe that He required a fresh act of intervention to supply the lacunas which He Himself had made. I question whether the former be not the loftier thought.

Be it as it may, I shall prize your book, both for itself, and as a proof that you are aware of the existence of such a person as

Your faithful servant, C. KINGSLEY.

[My father's old friend, the Rev. J. Brodie Innes, of Milton Brodie, who was for many years Vicar of Down, writes in the same spirit:

"We never attacked each other. Before I knew Mr. Darwin I had adopted, and publicly expressed, the principle that the study of natural history, geology, and science in general, should be pursued without reference to the Bible. That the Book of Nature and Scripture came from the same Divine source, ran in parallel lines, and when properly understood would never cross...

"His views on this subject were very much to the same effect from his side. Of course any conversations we may have had on purely religious subjects are as sacredly private now as in his life; but the quaint conclusion of one may be given. We had been speaking of the apparent contradiction of some supposed discoveries with the Book of Genesis; he said, 'you are (it would have been more correct to say you ought to be) a theologian, I am a naturalist, the lines are separate. I endeavour to discover facts without considering what is said in the Book of Genesis. I do not attack Moses, and I think Moses can take care of himself.' To the same effect he wrote more recently, 'I cannot remember that I ever published a word directly against religion or the clergy; but if you were to read a little pamphlet which I received a couple of days ago by a clergyman, you would laugh, and admit that I had some excuse for bitterness. After abusing me for two or three pages, in language sufficiently plain and emphatic to have satisfied any reasonable man, he sums up by saying that he has vainly searched the English language to find terms to express his contempt for me and all Darwinians.' In another letter, after I had left Down, he writes, 'We often differed, but you are one of those rare mortals from whom one can differ and yet feel no shade of animosity, and that is a thing [of] which I should feel very proud, if any one could say [it] of me.'

"On my last visit to Down, Mr. Darwin said, at his dinner-table, 'Brodie Innes and I have been fast friends for thirty years, and we never thoroughly agreed on any subject but once, and then we stared hard at each other, and thought one of us must be very ill.'"]

CHARLES DARWIN TO C. LYELL. Down, February 23rd [1860].

My dear Lyell,

That is a splendid answer of the father of Judge Crompton. How curious that the Judge should have hit on exactly the same points as yourself. It shows me what a capital lawyer you would have made, how many unjust acts you would have made appear just! But how much grander a field has science been than the law, though the latter might have made you Lord Kinnordy. I will, if there be another edition, enlarge on gradation in the eye, and on all forms coming from one prototype, so as to try and make both less glaringly improbable...

With respect to Bronn's objection that it cannot be shown how life arises, and likewise to a certain extent Asa Gray's remark that natural selection is not a vera causa, I was much interested by finding accidentally in Brewster's 'Life of Newton,' that Leibnitz objected to the law of gravity because Newton could not show what gravity itself is. As it has chanced, I have used in letters this very same argument, little knowing that any one had really thus objected to the law of gravity. Newton answers by saying that it is philosophy to make out the movements of a clock, though you do not know why the weight descends to the ground. Leibnitz further objected that the law of gravity was opposed to Natural Religion! Is this not curious? I really think I shall use the facts for some introductory remarks for my bigger book.

... You ask (I see) why we do not have monstrosities in higher animals; but when they live they are almost always sterile (even giants and dwarfs are GENERALLY sterile), and we do not know that Harvey's monster would have bred. There is I believe only one case on record of a peloric flower being fertile, and I cannot remember whether this reproduced itself.

To recur to the eye. I really think it would have been dishonest, not to have faced the difficulty; and worse (as Talleyrand would have said), it would have been impolitic I think, for it would have been thrown in my teeth, as H. Holland threw the bones of the ear, till Huxley shut him up by showing what a fine gradation occurred amongst living creatures.

I thank you much for your most pleasant letter.

Yours affectionately, C. DARWIN.

P.S. — I send a letter by Herbert Spencer, which you can read or not as you think fit. He puts, to my mind, the philosophy of the argument better than almost any one, at the close of the letter. I could make nothing of Dana's idealistic notions about species; but then, as Wollaston says, I have not a metaphysical head.

By the way, I have thrown at Wollaston's head, a paper by Alexander Jordan, who demonstrates metaphysically that all our cultivated races are Go-created species.

Wollaston misrepresents accidentally, to a wonderful extent, some passages in my book. He reviewed, without relooking at certain passages.

CHARLES DARWIN TO C. LYELL. Down, February 25th [1860].

... I cannot help wondering at your zeal about my book. I declare to heaven you seem to care as much about my book as I do myself. You have no right to be so eminently unselfish! I have taken off my spit [i.e. file] a letter of Ramsay's, as every geologist convert I think very important. By the way, I saw some time ago a letter from H.D. Rogers (Professor of Geology in the University of Glasgow. Born in the United States 1809, died 1866.) to Huxley, in which he goes very far with us...

CHARLES DARWIN TO J.D. HOOKER. Down, Saturday, March 3rd, [1860].

My dear Hooker,

What a day's work you had on that Thursday! I was not able to go to London till Monday, and then I was a fool for going, for, on Tuesday night, I had an attack of fever (with a touch of pleurisy), which came on like a lion, but went off as a lamb, but has shattered me a good bit.

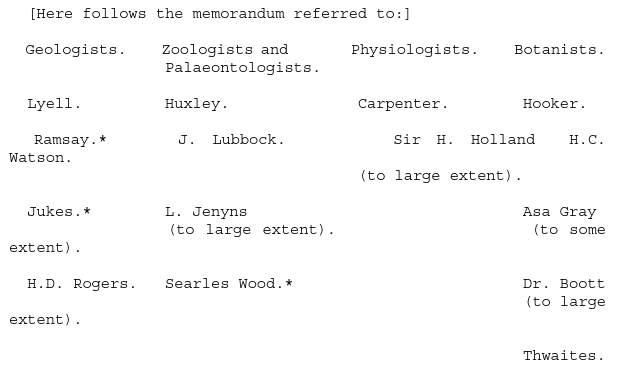

I was much interested by your last note... I think you expect too much in regard to change of opinion on the subject of Species. One large class of men, more especially I suspect of naturalists, never will care about ANY general question, of which old Gray, of the British Museum, may be taken as a type; and secondly, nearly all men past a moderate age, either in actual years or in mind, are, I am fully convinced, incapable of looking at facts under a new point of view. Seriously, I am astonished and rejoiced at the progress which the subject has made; look at the enclosed memorandum. (See table of names below.) — says my book will be forgotten in ten years, perhaps so; but, with such a list, I feel convinced the subject will not. The outsiders, as you say, are strong.

You say that you think that Bentham is touched, "but, like a wise man, holds his tongue." Perhaps you only mean that he cannot decide, otherwise I should think such silence the reverse of magnanimity; for if others behaved the same way, how would opinion ever progress? It is a dereliction of actual duty. (In a subsequent letter to Sir J.D. Hooker (March 12th, 1860), my father wrote, "I now quite understand Bentham's silence.")

I am so glad to hear about Thwaites. (Dr. G.J.K. Thwaites, who was born in 1811, established a reputation in this country as an expert microscopist, and an acute observer, working especially at cryptogamic botany. On his appointment as Director of the Botanic Gardens at Peradenyia, Ceylon, Dr. Thwaites devoted himself to the flora of Ceylon. As a result of this he has left numerous and valuable collections, a description of which he embodied in his 'Enumeratio Plantarum Zeylaniae' (1864). Dr. Thwaites was a fellow of the Linnean Society, but beyond the above facts little seems to have been recorded of his life. His death occurred in Ceylon on September 11th, 1882, in his seventy-second year. "Athenaeum", October 14th, 1882, page 500.)... I have had an astounding letter from Dr. Boott (The letter is enthusiastically laudatory, and obviously full of genuine feeling.); it might be turned into ridicule against him and me, so I will not send it to any one. He writes in a noble spirit of love of truth.

I wonder what Lindley thinks; probably too busy to read or think on the question.

I am vexed about Bentham's reticence, for it would have been of real value to know what parts appeared weakest to a man of his powers of observation.

Farewell, my dear Hooker, yours affectionately, C. DARWIN.

P.S. — Is not Harvey in the class of men who do not at all care for generalities? I remember your saying you could not get him to write on Distribution. I have found his works very unfruitful in every respect.

Joseph Beete Jukes, M.A., F.R.S., 1811-1869. He was educated at Cambridge, and from 1842 to 1846 he acted as naturalist to H.M.S. "Fly", on an exploring expedition in Australia and New Guinea. He was afterwards appointed Director of the Geological Survey of Ireland. He was the author of many papers, and of more than one good hand-book of geology.

Searles Valentine Wood, February 14, 1798-1880. Chiefly known for his work on the Mollusca of the 'Crag.')

[The following letter is of interest in connection with the mention of Mr. Bentham in the last letter:]

G. BENTHAM TO FRANCIS DARWIN. 25 Wilton Place, S.W., May 30th, 1882.

My dear Sir,

In compliance with your note which I received last night, I send herewith the letters I have from your father. I should have done so on seeing the general request published in the papers, but that I did not think there were any among them which could be of any use to you. Highly flattered as I was by the kind and friendly notice with which Mr. Darwin occasionally honoured me, I was never admitted into his intimacy, and he therefore never made any communications to me in relation to his views and labours. I have been throughout one of his most sincere admirers, and fully adopted his theories and conclusions, notwithstanding the severe pain and disappointment they at first occasioned me. On the day that his celebrated paper was read at the Linnean Society, July 1st, 1858, a long paper of mine had been set down for reading, in which, in commenting on the British Flora, I had collected a number of observations and facts illustrating what I then believed to be a fixity in species, however difficult it might be to assign their limits, and showing a tendency of abnormal forms produced by cultivation or otherwise, to withdraw within those original limits when left to themselves. Most fortunately my paper had to give way to Mr. Darwin's and when once that was read, I felt bound to defer mine for reconsideration; I began to entertain doubts on the subject, and on the appearance of the 'Origin of Species,' I was forced, however reluctantly, to give up my long-cherished convictions, the results of much labour and study, and I cancelled all that part of my paper which urged original fixity, and published only portions of the remainder in another form, chiefly in the 'Natural History Review.' I have since acknowledged on various occasions my full adoption of Mr. Darwin's views, and chiefly in my Presidential Address of 1863, and in my thirteenth and last address, issued in the form of a report to the British Association at its meeting at Belfast in 1874.

I prize so highly the letters that I have of Mr. Darwin's, that I should feel obliged by your returning them to me when you have done with them. Unfortunately I have not kept the envelopes, and Mr. Darwin usually only dated them by the month not by the year, so that they are not in any chronological order.

Yours very sincerely, GEORGE BENTHAM.

CHARLES DARWIN TO C. LYELL. Down [March] 12th [1860].

My dear Lyell,

Thinking over what we talked about, the high state of intellectual development of the old Grecians with the little or no subsequent improvement, being an apparent difficulty, it has just occurred to me that in fact the case harmonises perfectly with our views. The case would be a decided difficulty on the Lamarckian or Vestigian doctrine of necessary progression, but on the view which I hold of progression depending on the conditions, it is no objection at all, and harmonises with the other facts of progression in the corporeal structure of other animals. For in a state of anarchy, or despotism, or bad government, or after irruption of barbarians, force, strength, or ferocity, and not intellect, would be apt to gain the day.

We have so enjoyed your and Lady Lyell's visit.

Good-night. C. DARWIN.

P.S. — By an odd chance (for I had not alluded even to the subject) the ladies attacked me this evening, and threw the high state of old Grecians into my teeth, as an unanswerable difficulty, but by good chance I had my answer all pat, and silenced them. Hence I have thought it worth scribbling to you...

CHARLES DARWIN TO J. PRESTWICH. (Now Professor of Geology in the University of Oxford.) Down, March 12th [1860].

... At some future time, when you have a little leisure, and when you have read my 'Origin of Species,' I should esteem it a SINGULAR favour if you would send me any general criticisms. I do not mean of unreasonable length, but such as you could include in a letter. I have always admired your various memoirs so much that I should be eminently glad to receive your opinion, which might be of real service to me.

Pray do not suppose that I expect to CONVERT or PERVERT you; if I could stagger you in ever so slight a degree I should be satisfied; nor fear to annoy me by severe criticisms, for I have had some hearty kicks from some of my best friends. If it would not be disagreeable to you to send me your opinion, I certainly should be truly obliged...

CHARLES DARWIN TO ASA GRAY. Down, April 3rd [1860].

... I remember well the time when the thought of the eye made me cold all over, but I have got over this stage of the complaint, and now small trifling particulars of structure often make me very uncomfortable. The sight of a feather in a peacock's tail, whenever I gaze at it, makes me sick!..

You may like to hear about reviews on my book. Sedgwick (as I and Lyell feel CERTAIN from internal evidence) has reviewed me savagely and unfairly in the "Spectator". (See the quotations which follow the present letter.) The notice includes much abuse, and is hardly fair in several respects. He would actually lead any one, who was ignorant of geology, to suppose that I had invented the great gaps between successive geological formations, instead of its being an almost universally admitted dogma. But my dear old friend Sedgwick, with his noble heart, is old, and is rabid with indignation. It is hard to please every one; you may remember that in my last letter I asked you to leave out about the Weald denudation: I told Jukes this (who is head man of the Irish geological survey), and he blamed me much, for he believed every word of it, and thought it not at all exaggerated! In fact, geologists have no means of gauging the infinitude of past time. There has been one prodigy of a review, namely, an OPPOSED one (by Pictet (Francois Jules Pictet, in the 'Archives des Sciences de la Bibliotheque Universelle,' Mars 1860. The article is written in a courteous and considerate tone, and concludes by saying that the 'Origin' will be of real value to naturalists, especially if they are not led away by its seductive arguments to believe in the dangerous doctrine of modification. A passage which seems to have struck my father as being valuable, and opposite which he has made double pencil marks and written the word "good," is worth quoting: "La theorie de M. Darwin s'accorde mal avec l'histoire des types a formes bien tranchees et definies qui paraissent n'avoir vecu que pendant un temps limite. On en pourrait citer des centaines d'exemples, tel que les reptiles volants, les ichthyosaures, les belemnites, les ammonites, etc." Pictet was born in 1809, died 1872; he was Professor of Anatomy and Zoology at Geneva.), the palaeontologist, in the Bib. Universelle of Geneva) which is PERFECTLY fair and just, and I agree to every word he says; our only difference being that he attaches less weight to arguments in favour, and more to arguments opposed, than I do. Of all the opposed reviews, I think this the only quite fair one, and I never expected to see one. Please observe that I do not class your review by any means as opposed, though you think so yourself! It has done me MUCH too good service ever to appear in that rank in my eyes. But I fear I shall weary you with so much about my book. I should rather think there was a good chance of my becoming the most egotistical man in all Europe! What a proud pre-eminence! Well, you have helped to make me so and therefore you must forgive me if you can.

My dear Gray, ever yours most gratefully, C. DARWIN.

[In a letter to Sir Charles Lyell reference is made to Sedgwick's review in the "Spectator", March 24:

"I now feel certain that Sedgwick is the author of the article in the "Spectator". No one else could use such abusive terms. And what a misrepresentation of my notions! Any ignoramus would suppose that I had FIRST broached the doctrine, that the breaks between successive formations marked long intervals of time. It is very unfair. But poor dear old Sedgwick seems rabid on the question. "Demoralised understanding!" If ever I talk with him I will tell him that I never could believe that an inquisitor could be a good man: but now I know that a man may roast another, and yet have as kind and noble a heart as Sedgwick's."

The following passages are taken from the review:

"I need hardly go on any further with these objections. But I cannot conclude without expressing my detestation of the theory, because of its unflinching materialism; — because it has deserted the inductive track, the only track that leads to physical truth; — because it utterly repudiates final causes, and thereby indicates a demoralised understanding on the part of its advocates."

"Not that I believe that Darwin is an atheist; though I cannot but regard his materialism as atheistical. I think it untrue, because opposed to the obvious course of nature, and the very opposite of inductive truth. And I think it intensely mischievous."

"Each series of facts is laced together by a series of assumptions, and repetitions of the one false principle. You cannot make a good rope out of a string of air bubbles."

"But any startling and (supposed) novel paradox, maintained very boldly and with something of imposing plausibility, produces in some minds a kind of pleasing excitement which predisposes them in its favour; and if they are unused to careful reflection, and averse to the labour of accurate investigation, they will be likely to conclude that what is (apparently) ORIGINAL, must be a production of original GENIUS, and that anything very much opposed to prevailing notions must be a grand DISCOVERY, — in short, that whatever comes from the 'bottom of a well' must be the 'truth' supposed to be hidden there."

In a review in the December number of 'Macmillan's Magazine,' 1860, Fawcett vigorously defended my father from the charge of employing a false method of reasoning; a charge which occurs in Sedgwick's review, and was made at the time ad nauseam, in such phrases as: "This is not the true Baconian method." Fawcett repeated his defence at the meeting of the British Association in 1861. (See an interesting letter from my father in Mr. Stephen's 'Life of Henry Fawcett,' 1886, page 101.)]

CHARLES DARWIN TO W.B CARPENTER. Down, April 6th [1860].

My dear Carpenter,

I have this minute finished your review in the 'Med. Chirurg. Review.' (April 1860.) You must let me express my admiration at this most able essay, and I hope to God it will be largely read, for it must produce a great effect. I ought not, however, to express such warm admiration, for you give my book, I fear, far too much praise. But you have gratified me extremely; and though I hope I do not care very much for the approbation of the non-scientific readers, I cannot say that this is at all so with respect to such few men as yourself. I have not a criticism to make, for I object to not a word; and I admire all, so that I cannot pick out one part as better than the rest. It is all so well balanced. But it is impossible not to be struck with your extent of knowledge in geology, botany, and zoology. The extracts which you give from Hooker seem to me EXCELLENTLY chosen, and most forcible. I am so much pleased in what you say also about Lyell. In fact I am in a fit of enthusiasm, and had better write no more. With cordial thanks,

Yours very sincerely, C. DARWIN.

CHARLES DARWIN TO C. LYELL. Down, April 10th [1860].

My dear Lyell,

Thank you much for your note of the 4th; I am very glad to hear that you are at Torquay. I should have amused myself earlier by writing to you, but I have had Hooker and Huxley staying here, and they have fully occupied my time, as a little of anything is a full dose for me... There has been a plethora of reviews, and I am really quite sick of myself. There is a very long review by Carpenter in the 'Medical and Chirurg. Review,' very good and well balanced, but not brilliant. He discusses Hooker's books at as great length as mine, and makes excellent extracts; but I could not get Hooker to feel the least interest in being praised.

Carpenter speaks of you in thoroughly proper terms. There is a BRILLIANT review by Huxley ('Westminster Review,' April 1860.), with capital hits, but I do not know that he much advances the subject. I THINK I have convinced him that he has hardly allowed weight enough to the case of varieties of plants being in some degrees sterile.

To diverge from reviews: Asa Gray sends me from Wyman (who will write), a good case of all the pigs being black in the Everglades of Virginia. On asking about the cause, it seems (I have got capital analogous cases) that when the BLACK pigs eat a certain nut their bones become red, and they suffer to a certain extent, but that the WHITE pigs lose their hoofs and perish, "and we aid by SELECTION, for we kill most of the young white pigs." This was said by men who could hardly read. By the way, it is a great blow to me that you cannot admit the potency of natural selection. The more I think of it, the less I doubt its power for great and small changes. I have just read the 'Edinburgh' ('Edinburgh Review,' April 1860.), which without doubt is by — . It is extremely malignant, clever, and I fear will be very damaging. He is atrociously severe on Huxley's lecture, and very bitter against Hooker. So we three ENJOYED it together. Not that I really enjoyed it, for it made me uncomfortable for one night; but I have got quite over it to-day. It requires much study to appreciate all the bitter spite of many of the remarks against me; indeed I did not discover all myself. It scandalously misrepresents many parts. He misquotes some passages, altering words within inverted commas...

It is painful to be hated in the intense degree with which — hates me.

Now for a curious thing about my book, and then I have done. In last Saturday's "Gardeners' Chronicle" (April 7th, 1860.), a Mr. Patrick Matthew publishes a long extract from his work on 'Naval Timber and Arboriculture,' published in 1831, in which he briefly but completely anticipates the theory of Natural Selection. I have ordered the book, as some few passages are rather obscure, but it is certainly, I think, a complete but not developed anticipation! Erasmus always said that surely this would be shown to be the case some day. Anyhow, one may be excused in not having discovered the fact in a work on Naval Timber.

I heartily hope that your Torquay work may be successful. Give my kindest remembrances to Falconer, and I hope he is pretty well. Hooker and Huxley (with Mrs. Huxley) were extremely pleasant. But poor dear Hooker is tired to death of my book, and it is a marvel and a prodigy if you are not worse tired — if that be possible. Farewell, my dear Lyell,

Yours affectionately, C. DARWIN.

CHARLES DARWIN TO J.D. HOOKER. Down, [April 13th, 1860].

My dear Hooker,

Questions of priority so often lead to odious quarrels, that I should esteem it a great favour if you would read the enclosed. ((My father wrote ("Gardeners' Chronicle", 1860, page 362, April 21st): "I have been much interested by Mr. Patrick Matthew's communication in the number of your paper dated April 7th. I freely acknowledge that Mr. Matthew has anticipated by many years the explanation which I have offered of the origin of species, under the name of natural selection. I think that no one will feel surprised that neither I, nor apparently any other naturalist, had heard of Mr. Matthew's views, considering how briefly they are given, and that they appeared in the appendix to a work on Naval Timber and Arboriculture. I can do no more than offer my apologies to Mr. Matthew for my entire ignorance of this publication. If any other edition of my work is called for, I will insert to the foregoing effect." In spite of my father's recognition of his claims, Mr. Matthew remained unsatisfied, and complained that an article in the 'Saturday Analyst and Leader' was "scarcely fair in alluding to Mr. Darwin as the parent of the origin of species, seeing that I published the whole that Mr. Darwin attempts to prove, more than twenty-nine years ago." — "Saturday Analyst and Leader", November 24, 1860.) If you think it proper that I should send it (and of this there can hardly be any question), and if you think it full and ample enough, please alter the date to the day on which you post it, and let that be soon. The case in the "Gardeners' Chronicle" seems a LITTLE stronger than in Mr. Matthew's book, for the passages are therein scattered in three places; but it would be mere hair-splitting to notice that. If you object to my letter, please return it; but I do not expect that you will, but I thought that you would not object to run your eye over it. My dear Hooker, it is a great thing for me to have so good, true, and old a friend as you. I owe much for science to my friends.

Many thanks for Huxley's lecture. The latter part seemed to be grandly eloquent.

... I have gone over [the 'Edinburgh'] review again, and compared passages, and I am astonished at the misrepresentations. But I am glad I resolved not to answer. Perhaps it is selfish, but to answer and think more on the subject is too unpleasant. I am so sorry that Huxley by my means has been thus atrociously attacked. I do not suppose you much care about the gratuitous attack on you.

Lyell in his letter remarked that you seemed to him as if you were overworked. Do, pray, be cautious, and remember how many and many a man has done this — who thought it absurd till too late. I have often thought the same. You know that you were bad enough before your Indian journey.

CHARLES DARWIN TO C. LYELL. Down, April [1860].

My dear Lyell,

I was very glad to get your nice long letter from Torquay. A press of letters prevented me writing to Wells. I was particularly glad to hear what you thought about not noticing [the 'Edinburgh'] review. Hooker and Huxley thought it a sort of duty to point out the alteration of quoted citations, and there is truth in this remark; but I so hated the thought that I resolved not to do so. I shall come up to London on Saturday the 14th, for Sir B. Brodie's party, as I have an accumulation of things to do in London, and will (if I do not hear to the contrary) call about a quarter before ten on Sunday morning, and sit with you at breakfast, but will not sit long, and so take up much of your time. I must say one more word about our quasi-theological controversy about natural selection, and let me have your opinion when we meet in London. Do you consider that the successive variations in the size of the crop of the Pouter Pigeon, which man has accumulated to please his caprice, have been due to "the creative and sustaining powers of Brahma?" In the sense that an omnipotent and omniscient Deity must order and know everything, this must be admitted; yet, in honest truth, I can hardly admit it. It seems preposterous that a maker of a universe should care about the crop of a pigeon solely to please man's silly fancies. But if you agree with me in thinking such an interposition of the Deity uncalled for, I can see no reason whatever for believing in such interpositions in the case of natural beings, in which strange and admirable peculiarities have been naturally selected for the creature's own benefit. Imagine a Pouter in a state of nature wading into the water and then, being buoyed up by its inflated crop, sailing about in search of food. What admiration this would have excited — adaptation to the laws of hydrostatic pressure, etc. etc. For the life of me I cannot see any difficulty in natural selection producing the most exquisite structure, IF SUCH STRUCTURE CAN BE ARRIVED AT BY GRADATION, and I know from experience how hard it is to name any structure towards which at least some gradations are not known.