Various

The Illustrated London Reading Book

THE ROOKERY

Is that a rookery, papa?

Mr. S. It is. Do you hear what a cawing the birds make?

F. Yes; and I see them hopping about among the boughs. Pray, are not rooks the same with crows?

Mr. S. They are a species of crow. But they differ from the carrion crow and raven, in not feeding upon dead flesh, but upon corn and other seeds and grass, though, indeed, they pick up beetles and other insects and worms. See what a number of them have alighted on yonder ploughed field, almost blackening it over. They are searching for grubs and worms. The men in the field do not molest them, for they do a great deal of service by destroying grubs, which, if suffered to grow to winged insects, would injure the trees and plants.

F. Do all rooks live in rookeries?

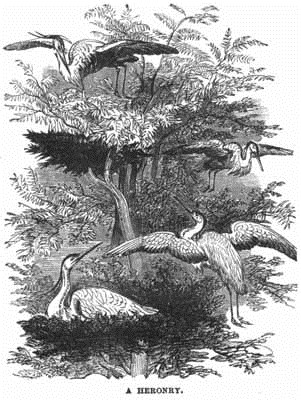

Mr. S. It is their nature to associate together, and they build in numbers of the same, or adjoining trees. They have no objection to the neighbourhood of man, but readily take to a plantation of tall trees, though it be close to a house; and this is commonly called a rookery. They will even fix their habitations on trees in the midst of towns.

F. I think a rookery is a sort of town itself.

Mr. S. It is—a village in the air, peopled with numerous inhabitants; and nothing can be more amusing than to view them all in motion, flying to and fro, and busied in their several occupations. The spring is their busiest time. Early in the year they begin to repair their nests, or build new ones.

F. Do they all work together, or every one for itself?

Mr. S. Each pair, after they have coupled, builds its own nest; and, instead of helping, they are very apt to steal the materials from one another. If both birds go out at once in search of sticks, they often find at their return the work all destroyed, and the materials carried off. However, I have met with a story which shows that they are not without some sense of the criminality of thieving. There was in a rookery a lazy pair of rooks, who never went out to get sticks for themselves, but made a practice of watching when their neighbours were abroad, and helping themselves from their nests. They had served most of the community in this manner, and by these means had just finished their own nest; when all the other rooks, in a rage, fell upon them at once, pulled their nest in pieces, beat them soundly, and drove them from their society.

F. But why do they live together, if they do not help one another?

Mr. S. They probably receive pleasure from the company of their own kind, as men and various other creatures do. Then, though they do not assist one another in building, they are mutually serviceable in many ways. If a large bird of prey hovers about a rookery for the purpose of carrying away the young ones, they all unite to drive him away. And when they are feeding in a flock, several are placed as sentinels upon the trees all round, to give the alarm if any danger approaches.

F. Do rooks always keep to the same trees?

Mr. S. Yes; they are much attached to them, and when the trees happen to be cut down, they seem greatly distressed, and keep hovering about them as they are falling, and will scarcely desert them when they lie on the ground.

F. I suppose they feel as we should if our town was burned down, or overthrown by an earthquake.

Mr. S. No doubt. The societies of animals greatly resemble those of men; and that of rooks is like those of men in the savage state, such as the communities of the North American Indians. It is a sort of league for mutual aid and defence, but in which every one is left to do as he pleases, without any obligation to employ himself for the whole body. Others unite in a manner resembling more civilised societies of men. This is the case with the heavers. They perform great public works by the united efforts of the whole community—such as damming up streams and constructing mounds for their habitations. As these are works of great art and labour, some of them probably act under the direction of others, and are compelled to work, whether they will or not. Many curious stories are told to this purpose by those who have observed them in their remotest haunts, where they exercise their full sagacity.

F. But are they all true?

Mr. S. That is more than I can answer for; yet what we certainly know of the economy of bees may justify us in believing extraordinary things of the sagacity of animals. The society of bees goes further than that of beavers, and in some respects beyond most among men themselves. They not only inhabit a common dwelling, and perform great works in common, but they lay up a store of provision, which is the property of the whole community, and is not used except at certain seasons and under certain regulations. A bee-hive is a true image of a commonwealth, where no member acts for himself alone, but for the whole body.

Evenings at Home.

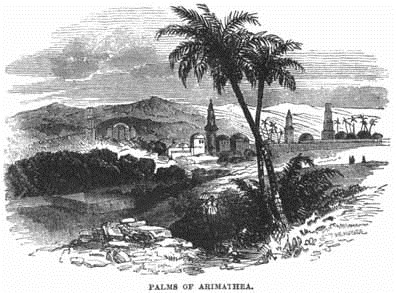

PALMS

These beautiful trees may be ranked among the noblest specimens of vegetation; and their tall, slender, unbranched stems, crowned by elegant feathery foliage, composed of a cluster of gigantic leaves, render them, although of several varieties, different in appearance from all other trees. In some kinds of palm the stem is irregularly thick; in others, slender as a reed. It is scaly in one species, and prickly in another. In the Palma real, in Cuba, the stem swells out like a spindle in the middle. At the summit of these stems, which in some cases attain an altitude of upwards of 180 feet, a crown of leaves, either feathery or fan-shaped (for there is not a great variety in their general form), spreads out on all sides, the leaves being frequently from twelve to fifteen feet in length. In some species the foliage is of a dark green and shining surface, like that of a laurel or holly; in others, silvery on the under-side, as in the willow; and there is one species of palm with a fan-shaped leaf, adorned with concentric blue and yellow rings, like the "eyes" of a peacock's tail.

The flowers of most of the palms are as beautiful as the trees. Those of the Palma real are of a brilliant white, rendering them visible from a great distance; but, generally, the blossoms are of a pale yellow. To these succeed very different forms of fruit: in one species it consists of a cluster of egg-shaped berries, sometimes seventy or eighty in number, of a brilliant purple and gold colour, which form a wholesome food.

South America contains the finest specimens, as well as the most numerous varieties of palm: in Asia the tree is not very common; and of the African palms but little is yet known, with the exception of the date palm, the most important to man of the whole tribe, though far less beautiful than the other species.

THE PALM-TREE

It waved not through an Eastern sky,

Beside a fount of Araby;

It was not fann'd by Southern breeze

In some green isle of Indian seas;

Nor did its graceful shadow sleep

O'er stream of Afric, lone and deep.

But fair the exiled Palm-tree grew,

'Midst foliage of no kindred hue:

Through the laburnum's dropping gold

Rose the light shaft of Orient mould;

And Europe's violets, faintly sweet,

Purpled the moss-beds at its feet.

Strange look'd it there!–the willow stream'd

Where silv'ry waters near it gleam'd;

The lime-bough lured the honey-bee

To murmur by the Desert's tree,

And showers of snowy roses made

A lustre in its fan-like shade.

There came an eve of festal hours—

Rich music fill'd that garden's bowers;

Lamps, that from flow'ring branches hung,

On sparks of dew soft colours flung;

And bright forms glanced—a fairy show,

Under the blossoms to and fro.

But one, a lone one, 'midst the throng,

Seem'd reckless all of dance or song:

He was a youth of dusky mien,

Whereon the Indian sun had been;

Of crested brow, and long black hair—

A stranger, like the Palm-tree, there.

And slowly, sadly, moved his plumes,

Glittering athwart the leafy glooms:

He pass'd the pale green olives by,

Nor won the chesnut flowers his eye;

But when to that sole Palm he came,

Then shot a rapture through his frame.

To him, to him its rustling spoke;

The silence of his soul it broke.

It whisper'd of his own bright isle,

That lit the ocean with a smile.

Aye to his ear that native tone

Had something of the sea-wave's moan.

His mother's cabin-home, that lay

Where feathery cocoos fringe the bay;

The dashing of his brethren's oar,

The conch-note heard along the shore—

All through his wak'ning bosom swept:

He clasp'd his country's tree, and wept.

Oh! scorn him not. The strength whereby

The patriot girds himself to die;

The unconquerable power which fills

The foeman battling on his hills:

These have one fountain deep and clear,

The same whence gush'd that child-like tear!—

Mrs. Hemans.

A CHAPTER ON DOGS

Newfoundland Dogs are employed in drawing sledges laden with fish, wood, and other articles, and from their strength and docility are of considerable importance. The courage, devotion, and skill of this noble animal in the rescue of persons from drowning is well known; and on the banks of the Seine, at Paris, these qualities have been applied to a singular purpose. Ten Newfoundland dogs are there trained to act as servants to the Humane Society; and the rapidity with which they cross and re-cross the river, and come and go, at the voice of their trainer, is described as being most interesting to witness. Handsome kennels have been erected for their dwellings on the bridges.

DALMATIAN DOG

There is a breed of very handsome dogs called by this name, of a white colour, thickly spotted with black: it is classed among the hounds. This species is said to have been brought from India, and is not remarkable for either fine scent or intelligence. The Dalmatian Dog is generally kept in our country as an appendage to the carriage, and is bred up in the stable with the horses; it consequently seldom receives that kind of training which is calculated to call forth any good qualities it may possess.

TERRIER

The Terrier is a valuable dog in the house and farm, keeping both domains free from intruders, either in the shape of thieves or vermin. The mischief effected by rats is almost incredible; it has been said that, in some cases, in the article of corn, these little animals consume a quantity in food equal in value to the rent of the farm. Here the terrier is a most valuable assistant, in helping the farmer to rid himself of his enemies. The Scotch Terrier is very common in the greater part of the Western Islands of Scotland, and some of the species are greatly admired. Her Majesty Queen Victoria possesses one from Islay—a faithful, affectionate creature, yet with all the spirit and determination that belong to his breed.

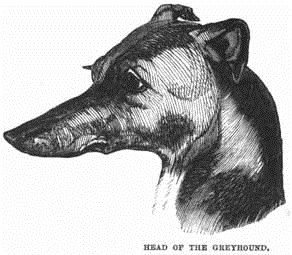

THE GREYHOUND

The modern smooth-haired Greyhound of England is a very elegant dog, not surpassed in speed and endurance by that of any other country. Hunting the deer with a kind of greyhound of a larger size was formerly a favourite diversion; and Queen Elizabeth was gratified by seeing, on one occasion, from a turret, sixteen deer pulled down by greyhounds upon the lawn at Cowdry Park, in Sussex.

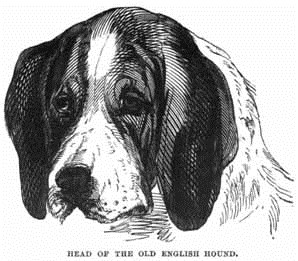

OLD ENGLISH HOUND

The dog we now call the Staghound appears to answer better than any other to the description given to us of the old English Hound, which was so much valued when the country was less enclosed, and the numerous and extensive forests were the harbours of the wild deer. This hound, with the harrier, were for many centuries the only hunting dogs.

SHEPHERD'S DOG

Instinct and education combine to fit this dog for our service: the pointer will act without any great degree of instruction, and the setter will crouch; but the Sheep Dog, especially if he has the example of an older one, will, almost without the teaching of his master, become everything he could wish, and be obedient to every order, even to the slightest motion of the hand. If the 's dog be but with his master, he appears to be perfectly content, rarely mingling with his kind, and generally shunning the advances of strangers; but the moment duty calls, his eye brightens, he springs up with eagerness, and exhibits a sagacity, fidelity, and devotion rarely equalled even by man himself.

BULL-DOG

Of all dogs, none surpass in obstinacy and ferocity the Bull-dog. The head is broad and thick, the lower jaw generally projects so that the under teeth advance beyond the upper, the eyes are scowling, and the whole expression calculated to inspire terror. It is remarkable for the pertinacity with which it maintains its hold of any animal it may have seized, and is, therefore, much used in the barbarous practice of bull-baiting, so common in some countries, and but lately abolished in England.

LORD BACON

In those prescient views by which the genius of Lord Bacon has often anticipated the institutions and the discoveries of succeeding times, there was one important object which even his foresight does not appear to have contemplated. Lord Bacon did not foresee that the English language would one day be capable of embalming all that philosophy can discover, or poetry can invent; that his country would at length possess a national literature of its own, and that it would exult in classical compositions, which might be appreciated with the finest models of antiquity. His taste was far unequal to his invention. So little did he esteem the language of his country, that his favourite works were composed in Latin; and he was anxious to have what he had written in English preserved in that "universal language which may last as long as books last."

It would have surprised Bacon to have been told that the most learned men in Europe have studied English authors to learn to think and to write. Our philosopher was surely somewhat mortified, when, in his dedication of the Essays, he observed, that, "Of all my other works, my Essays have been most current; for that, as it seems, they come home to men's business and bosoms." It is too much to hope to find in a vast and profound inventor, a writer also who bestows immortality on his language. The English language is the only object, in his great survey of art and of nature, which owes nothing of its excellence to the genius of Bacon.

He had reason, indeed, to be mortified at the reception of his philosophical works; and Dr. Rowley, even, some years after the death of his illustrious master, had occasion to observe, "His fame is greater, and sounds louder in foreign parts abroad than at home in his own nation; thereby verifying that Divine sentence, 'A Prophet is not without honour, save in his own country and in his own house,'" Even the men of genius, who ought to have comprehended this new source of knowledge thus opened to them, reluctantly entered into it: so repugnant are we to give up ancient errors, which time and habit have made a part of ourselves.

D'Israeli.

THE LILIES OF THE FIELD

Flowers! when the Saviour's calm, benignant eye

Fell on your gentle beauty; when from you

That heavenly lesson for all hearts he drew.

Eternal, universal as the sky;

Then in the bosom of your purity

A voice He set, as in a temple shrine,

That Life's quick travellers ne'er might pass you by

Unwarn'd of that sweet oracle divine.

And though too oft its low, celestial sound

By the harsh notes of work-day care is drown'd,

And the loud steps of vain, unlist'ning haste,

Yet the great lesson hath no tone of power,

Mightier to reach the soul in thought's hush'd hour,

Than yours, meek lilies, chosen thus, and graced.

Mrs. Hemans.

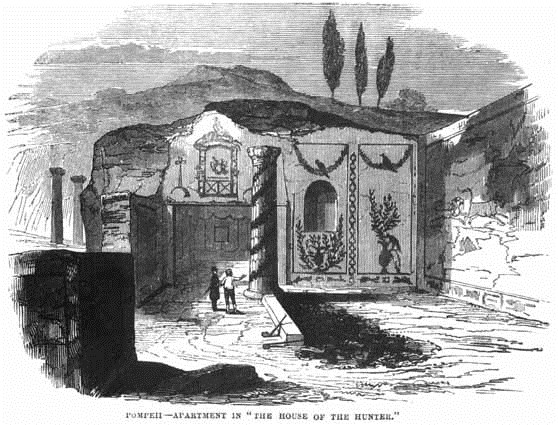

POMPEII

The earliest and one of the most fatal eruptions of Mount Vesuvius that is mentioned in history took place in the year 79, during the reign of the Emperor Titus. All Campagna was filled with consternation, and the country was overwhelmed with devastation in every direction; towns, villages, palaces, and their inhabitants were consumed by molten lava, and hidden from the sight by showers of volcanic stones, cinders, and ashes.

Pompeii had suffered severely from an earthquake sixteen years before, but had been rebuilt and adorned with many a stately building, particularly a magnificent theatre, where thousands were assembled to see the gladiators when this tremendous visitation burst upon the devoted city, and buried it to a considerable depth with the fiery materials thrown from the crater. "Day was turned to night," says a classic author, "and night into darkness; an inexpressible quantity of dust and ashes was poured out, deluging land, sea, and air, and burying two entire cities, Pompeii and Herculaneum, whilst the people were sitting in the theatre."

Many parts of Pompeii have, at various times, been excavated, so as to allow visitors to examine the houses and streets; and in February, 1846, the house of the Hunter was finally cleared, as it appears in the Engraving. This is an interesting dwelling, and was very likely the residence of a man of wealth, fond of the chase. A painting on the right occupies one side of the large room, and here are represented wild animals, the lion chasing a bull, &c. The upper part of the house is raised, where stands a gaily-painted column—red and yellow in festoons; behind which, and over a doorway, is a fresco painting of a summer-house perhaps a representation of some country-seat of the proprietor, on either side are hunting-horns. The most beautiful painting in this room represents a Vulcan at his forge, assisted by three dusky, aged figures. In the niche of the outward room a small statue was found, in terra cotta (baked clay). The architecture of this house is singularly rich in decoration, and the paintings, particularly those of the birds and vases, very bright vivid.

At this time, too, some very perfect skeletons were discovered in a house near the theatre, and near the hand of one of them were found thirty-seven pieces of silver and two gold coins; some of the former were attached to the handle of a key. The unhappy beings who were perished may have been the inmates of the dwelling. We know, from the account written by Pliny, that the young and active had plenty of time for escape, and this is the reason why so few skeletons have been found in Pompeii.

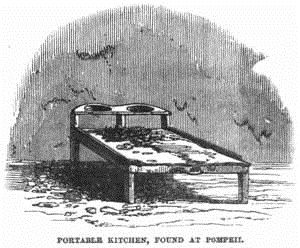

In a place excavated at the expense of the Empress of Russia was found a portable kitchen (represented above), made of iron, with two round holes for boiling pots. The tabular top received the fire for placing other utensils upon, and by a handle in the front it could be moved when necessary.

THE NIGHTINGALE AND GLOWWORM

A Nightingale that all day long

Had cheer'd the village with his song,

Nor yet at eve his note suspended,

Nor yet when even-tide was ended—

Began to feel, as well he might,

The keen demands of appetite:

When, looking eagerly around,

He spied, far off upon the ground,

A something shining in the dark,

And knew the glowworm by his spark:

So stooping down from hawthorn top,

He thought to put him in his crop.

The worm, aware of his intent,

Harangued him thus, right eloquent:—

"Did you admire my lamp," quoth he,

"As much as I your minstrelsy,

You would abhor to do me wrong,

As much as I to spoil your song;

For 'twas the self-same power Divine

Taught you to sing and me to shine,

That you with music, I with light,

Might beautify and cheer the night."

The songster heard his short oration,

And, warbling out his approbation,

Released him, as my story tells,

And found a supper somewhere else.

Cowper.

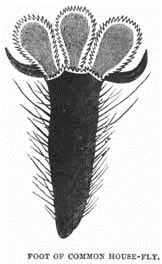

THE INVISIBLE WORLD REVEALED BY THE MICROSCOPE

A fact not less startling than would be the realisation of the imaginings of Shakespeare and of Milton, or of the speculations of Locke and of Bacon, admits of easy demonstration, namely, that the air, the earth, and the waters teem with numberless myriads of creatures, which are as unknown and as unapproachable to the great mass of mankind, as are the inhabitants of another planet. It may, indeed, be questioned, whether, if the telescope could bring within the reach of our observation the living things that dwell in the worlds around us, life would be there displayed in forms more diversified, in organisms more marvellous, under conditions more unlike those in which animal existence appears to our unassisted senses, than may be discovered in the leaves of every forest, in the flowers of every garden, and in the waters of every rivulet, by that noblest instrument of natural philosophy, the Microscope.

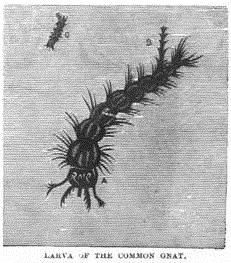

Larva of the Common Gnat.

A. The body and head of the larva (magnified).

B. The respiratory apparatus, situated in the tail.

C. Natural size.

To an intelligent person, who has previously obtained a general idea of the nature of the Objects about to be submitted to his inspection, a group of living animalcules, seen under a powerful microscope for the first time, presents a scene of extraordinary interest, and never fails to call forth an expression of amazement and admiration. This statement admits of an easy illustration: for example, from some water containing aquatic plants, collected from a pond on Clapham Common, I select a small twig, to which are attached a few delicate flakes, apparently of slime or jelly; some minute fibres, standing erect here and there on the twig, are also dimly visible to the naked eye. This twig, with a drop or two of the water, we will put between two thin plates of glass, and place under the field of view of a microscope, having lenses that magnify the image of an object 200 times in linear dimensions.

Upon looking through the instrument, we find the fluid swarming with animals of various shapes and magnitudes. Some are darting through the water with great rapidity, while others are pursuing and devouring creatures more infinitesimal than themselves. Many are attached to the twig by long delicate threads, several have their bodies inclosed in a transparent tube, from one end of which the animal partly protrudes and then recedes, while others are covered by an elegant shell or case. The minutest kinds, many of which are so small that millions might be contained in a single drop of water, appear like mere animated globules, free, single, and of various colours, sporting about in every direction. Numerous species resemble pearly or opaline cups or vases, fringed round the margin with delicate fibres, that are in constant oscillation. Some of these are attached by spiral tendrils; others are united by a slender stem to one common trunk, appearing like a bunch of hare-bells; others are of a globular form, and grouped together in a definite pattern, on a tabular or spherical membranous case, for a certain period of their existence, and ultimately become detached and locomotive, while many are permanently clustered together, and die if separated from the parent mass. They have no organs of progressive motion, similar to those of beasts, birds, or fishes; and though many species are destitute of eyes, yet possess an accurate perception of the presence of other bodies, and pursue and capture their prey with unerring purpose.

Mantell's Thoughts on Animalcules.

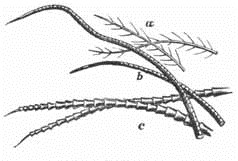

Hair, Greatly Magnified.

A. Hairs of the Bat.

B. Of the Mole.

C. Of the Mouse.