Various

The Illustrated London Reading Book

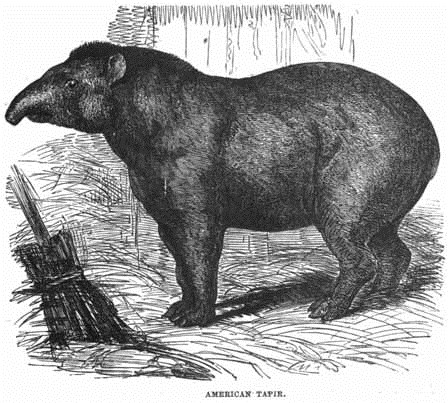

THE AMERICAN TAPIR

There are but three known species of the Tapir, two of which—the Peccary and the Tapir—are natives of South America, the other of Sumatra and Malacca. Its anatomy is much like that of the rhinoceros, while in general form the tapir reminds us of the hog. It is a massive and powerful animal, and its fondness for the water is almost as strong as that displayed by the hippopotamus. It swims and dives admirably, and will remain submerged for many minutes, rising to the surface for breath, and then again plunging in. When hunted or wounded, it always, if possible, makes for the water; and in its nightly wanderings will traverse rivers and lakes in search of food, or for pleasure. The female is very attentive to her young one, leading it about on the land, and accustoming it at an early period to enter the water, where it plunges and plays before its parent, who seems to act as its instructress, the male taking no share in the work.

The tapir is very common in the warm regions of South America, where it inhabits the forests, leading a solitary life, and seldom stirring from its retreat during the day, which it passes in a state of tranquil slumber. During the night, its season of activity, it wanders forth in search of food, which consists of water-melons, gourds, young shoots of brushwood, &c.; but, like the hog, it is not very particular in its diet. Its senses of smell and hearing are extremely acute, and serve to give timely notice of the approach of enemies. Defended by its tough thick hide, it is capable of forcing its way through the thick underwood in any direction it pleases: when thus driving onwards, it carries its head low, and, as it were, ploughs its course.

The most formidable enemy of this animal, if we except man, is the jaguar; and it is asserted that when that tiger of the American forest throws itself upon the tapir, the latter rushes through the most dense and tangled underwood, bruising its enemy, and generally succeeds in dislodging him.

The snout of the tapir greatly reminds one of the trunk of the elephant; for although it is not so long, it is very flexible, and the animal makes excellent use of it as a crook to draw down twigs to the mouth, or grasp fruit or bunches of herbage: it has nostrils at the extremity, but there is no finger-like appendage.

In its disposition the tapir is peaceful and quiet, and, unless hard pressed, never attempts to attack either man or beast; when, however, the hunter's dogs surround it, it defends itself very vigorously with its teeth, inflicting terrible wounds, and uttering a cry like a shrill kind of whistle, which is in strange contrast with the massive bulk of the animal.

The Indian tapir greatly resembles its American relative; it feeds on vegetables, and is very partial to the sugar-cane. It is larger than the American, and the snout is longer and more like the trunk of the elephant. The most striking difference, however, between the eastern and western animal is in colour. Instead of being the uniform dusky-bay tint of the American, the Indian is strangely particoloured. The head, neck, fore-limbs, and fore-quarters are quite black; the body then becomes suddenly white or greyish-white, and so continues to about half-way over the hind-quarters, when the black again commences abruptly, spreading over the legs. The animal, in fact, looks just as if it were covered round the body with a white horse-cloth.

Though the flesh of both the Indian and American tapir is dry and disagreeable as an article of food, still the animal might be domesticated with advantage, and employed as a beast of burthen, its docility and great strength being strong recommendations.

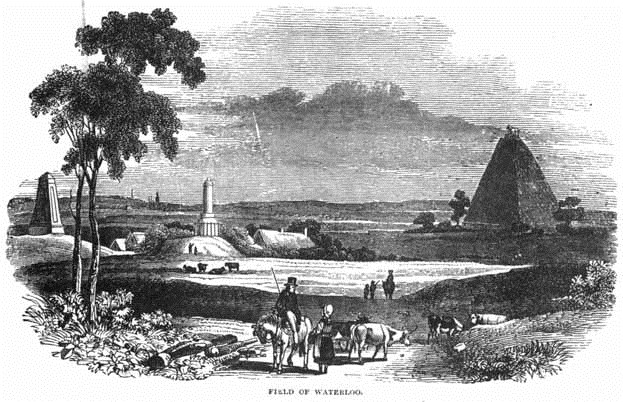

THE FIELD OF WATERLOO

Waterloo is a considerable village of Belgium, containing about 1600 inhabitants; and the Field of Waterloo, so celebrated as the scene of the battle between two of the greatest generals who ever lived, is about two miles from it. It was very far from a strong position to be chosen for this purpose, but, no doubt, was the best the country afforded. A gently rising ground, not steep enough in any part to prevent a rush of infantry at double-quick time, except in the dell on the left of the road, near the farm of La Haye Sainte; and along the crest of the hill a scrubby hedge and low bank fencing a narrow country road. This was all, except La Haye Sainte and Hougoumont. This chateau, or country-seat, one of those continental residences which unite in them something of the nature of a castle and a farm-house, was the residence of a Belgic gentleman. It stands on a little eminence near the main road leading from Brussels to Nivelles. The buildings consisted of an old tower and a chapel, and a number of offices, partly surrounded by a farm-yard. The garden was enclosed by a high and strong wall; round the garden was a wood or orchard, which was enclosed by a thick hedge, concealing the wall. The position of the place was deemed so important by the Duke of Wellington, that he took possession of the Château of Goumont, as it was called, on the 17th of June, and the troops were soon busily preparing for the approaching contest, by perforating the walls, making loop-holes for the fire of the musketry, and erecting scaffolding for the purpose of firing from the top.

The importance of this place was also so well appreciated by Bonaparte, that the battle of the 18th began by his attacking Hougoumont. This name, which was bestowed upon it by the mistake of our great commander, has quite superseded the real one of Château Goumont. The ruins are among the most interesting of all the points connected with this memorable place, for the struggle there was perhaps the fiercest. The battered walls, the dismantled and fire-stained chapel, which remained standing through all the attack, still may be seen among the wreck of its once beautiful garden; while huge blackened beams, which have fallen upon the crumbling heaps of stone and plaster, are lying in all directions.

On the field of battle are two interesting monuments: one, to the memory of the Hon. Sir Alexander Gordon, brother to the Earl of Aberdeen, who there terminated a short but glorious career, at the age of twenty-nine, and "fell in the blaze of his fame;" the other, to some brave officers of the German Legion, who likewise died under circumstances of peculiar distinction. There is also, on an enormous mound, a colossal lion of bronze, erected by the Belgians to the honour of the Prince of Orange, who was wounded at, or near, to the spot.

Against the walls of the church of the village of Waterloo are many beautiful marble tablets, with the most affecting inscriptions, records of men of various countries, who expired on that solemn and memorable occasion in supporting a common cause. Many of these brave men were buried in a cemetery at a short distance from the village.

THE TWO OWLS AND THE SPARROW

Two formal Owls together sat,

Conferring thus in solemn chat:

"How is the modern taste decay'd!

Where's the respect to wisdom paid?

Our worth the Grecian sages knew;

They gave our sires the honour due:

They weigh'd the dignity of fowls,

And pry'd into the depth of Owls.

Athens, the seat of earned fame,

With gen'ral voice revered our name;

On merit title was conferr'd,

And all adored th' Athenian bird."

"Brother, you reason well," replies

The solemn mate, with half-shut eyes:

"Right: Athens was the seat of learning,

And truly wisdom is discerning.

Besides, on Pallas' helm we sit,

The type and ornament of wit:

But now, alas! we're quite neglected,

And a pert Sparrow's more respected."

A Sparrow, who was lodged beside,

O'erhears them sooth each other's pride.

And thus he nimbly vents his heat:

"Who meets a fool must find conceit.

I grant you were at Athens graced,

And on Minerva's helm were placed;

But ev'ry bird that wings the sky,

Except an Owl, can tell you why.

From hence they taught their schools to know

How false we judge by outward show;

That we should never looks esteem,

Since fools as wise as you might seem.

Would you contempt and scorn avoid,

Let your vain-glory be destroy'd:

Humble your arrogance of thought,

Pursue the ways by Nature taught:

So shall you find delicious fare,

And grateful farmers praise your care;

So shall sleek mice your chase reward,

And no keen cat find more regard."

Gay.

THE BEETLE

See the beetle that crawls in your way,

And runs to escape from your feet;

His house is a hole in the clay,

And the bright morning dew is his meat.

But if you more closely behold

This insect you think is so mean,

You will find him all spangled with gold,

And shining with crimson and green.

Tho' the peacock's bright plumage we prize,

As he spreads out his tail to the sun,

The beetle we should not despise,

Nor over him carelessly run.

They both the same Maker declare—

They both the same wisdom display,

The same beauties in common they share—

Both are equally happy and gay.

And remember that while you would fear

The beautiful peacock to kill,

You would tread on the poor beetle here,

And think you were doing no ill.

But though 'tis so humble, be sure,

As mangled and bleeding it lies,

A pain as severe 'twill endure,

As if 'twere a giant that dies.

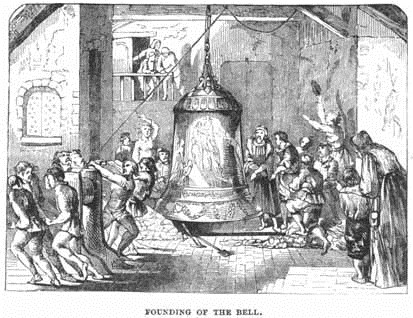

THE FOUNDING OF THE BELL

Hark! how the furnace pants and roars,

Hark! how the molten metal pours,

As, bursting from its iron doors,

It glitters in the sun.

Now through the ready mould it flows,

Seething and hissing as it goes,

And filling every crevice up,

As the red vintage fills the cup—

Hurra! the work is done!

Unswathe him now. Take off each stay

That binds him to his couch of clay,

And let him struggle into day!

Let chain and pulley run,

With yielding crank and steady rope,

Until he rise from rim to cope,

In rounded beauty, ribb'd in strength,

Without a flaw in all his length—

Hurra! the work is done!

The clapper on his giant side

Shall ring no peal for blushing bride,

For birth, or death, or new-year tide,

Or festival begun!

A nation's joy alone shall be

The signal for his revelry;

And for a nation's woes alone

His melancholy tongue shall moan—

Hurra! the work is done!

Borne on the gale, deep-toned and clear,

His long, loud summons shall we hear,

When statesmen to their country dear

Their mortal race have run;

When mighty Monarchs yield their breath,

And patriots sleep the sleep of death,

Then shall he raise his voice of gloom,

And peal a requiem o'er their tomb—

Hurra! the work is done!

Should foemen lift their haughty hand,

And dare invade us where we stand,

Fast by the altars of our land

We'll gather every one;

And he shall ring the loud alarm,

To call the multitudes to arm,

From distant field and forest brown,

And teeming alleys of the town—

Hurra! the work is done!

And as the solemn boom they hear,

Old men shall grasp the idle spear,

Laid by to rust for many a year,

And to the struggle run:

Young men shall leave their toils or books,

Or turn to swords their pruning-hooks;

And maids have sweetest smiles for those

Who battle with their country's foes—

Hurra! the work is done!

And when the cannon's iron throat

Shall bear the news to dells remote,

And trumpet blast resound the note—

That victory is won;

When down the wind the banner drops,

And bonfires blaze on mountain tops,

His sides shall glow with fierce delight,

And ring glad peals from morn to night—

Hurra! the work is done!

But of such themes forbear to tell—

May never War awake this bell

To sound the tocsin or the knell—

Hush'd be the alarum gun.

Sheath'd be the sword! and may his voice

But call the nations to rejoice

That War his tatter'd flag has furl'd,

And vanish'd from a wiser world—

Hurra! the work is done!

Still may he ring when struggles cease—

Still may he ring for joy's increase,

For progress in the arts of peace,

And friendly trophies won;

When rival nations join their hands,

When plenty crowns the happy lands,

When Knowledge gives new blessings birth,

And Freedom reigns o'er all the earth—

Hurra! the work is done!

Mackay.

NAPOLEON

With his passions, and in spite of his errors, Napoleon was, taking him all in all, the greatest warrior of modern times. He carried into battle a stoical courage, a profoundly calculated tenacity, a mind fertile in sudden inspirations, which, by unlooked-for resources, disconcerted the plans of his enemy. Let us beware of attributing a long series of success to the organic power of the masses which he set in motion. The most experienced eye could scarcely discover in them any thing but elements of disorder. Still less, let it be said, that he was a successful captain because he was a mighty Monarch. Of all his campaigns, the most memorable are the campaign of the Adige, where the general of yesterday, commanding an army by no means numerous, and at first badly appointed, placed himself at once above Turenne, and on a level with Frederick; and the campaign in France in 1814, when, reduced to a handful of harrassed troops, he combated a force of ten times their number. The last flashes of Imperial lightning still dazzled the eyes of our enemies; and it was a fine sight to see the bounds of the old lion, tracked, hunted down, beset—presenting a lively picture of the days of his youth, when his powers developed themselves in the fields of carnage.

Napoleon possessed, in an eminent degree, the faculties requisite for the profession of arms; temperate and robust; watching and sleeping at pleasure; appearing unawares where he was least expected: he did not disregard details, to which important results are sometimes attached. The hand which had just traced rules for the government of many millions of men, would frequently rectify an incorrect statement of the situation of a regiment, or write down whence two hundred conscripts were to be obtained, and from what magazine their shoes were to be taken. A patient, and an easy interlocutor, he was a home questioner, and he could listen—a rare talent in the grandees of the earth. He carried with him into battle a cool and impassable courage. Never was mind so deeply meditative, more fertile in rapid and sudden illuminations. On becoming Emperor he ceased not to be the soldier. If his activity decreased with the progress of age, that was owing to the decrease of his physical powers. In games of mingled calculation and hazard the greater the advantages which a man seeks to obtain the greater risks he must run. It is precisely this that renders the deceitful science of conquerors so calamitous to nations.

Napoleon, though naturally adventurous, was not deficient in consistency or method; and he wasted neither his soldiers nor his treasures where the authority of his name sufficed. What he could obtain by negotiations or by artifice, he required not by force of arms. The sword, although drawn from the scabbard, was not stained with blood unless it was impossible to attain the end in view by a manoeuvre. Always ready to fight, he chose habitually the occasion and the ground: out of fifty battles which he fought, he was the assailant in at least forty. Other generals have equalled him in the art of disposing troops on the ground; some have given battle as well as he did—we could mention several who have received it better; but in the manner of directing an offensive campaign he has surpassed all. The wars in Spain and Russia prove nothing in disparagement of his genius. It is not by the rules of Montecuculi and Turenne, manoeuvring on the Renchen, that we ought to judge of such enterprises: the first warred to such or such winter quarters; the other to subdue the world. It frequently behoved him not merely to gain a battle, but to gain it in such a manner as to astound Europe and to produce gigantic results. Thus political views were incessantly interfering with the strategic genius; and to appreciate him properly, we must not confine ourselves within the limits of the art of war. This art is not composed exclusively of technical details; it has also its philosophy.

To find in this elevated region a rival of Napoleon, we must go back to the times when the feudal institutions had not yet broken the unity of the ancient nations. The founders of religion alone have exercised over their disciples an authority comparable with that which made him the absolute master of his army. This moral power became fatal to him, because he strove to avail himself of it even against the ascendancy of material force, and because it led him to despise positive rules, the long violation of which will not remain unpunished. When pride was bringing Napoleon towards his fall, he happened to say, "France has more need of me than I have of France." He spoke the truth: but why had he become necessary? Because he had committed the destiny of France to the chances of an interminable war: because, in spite of the resources of his genius, that war, rendered daily more hazardous by his staking the whole of his force and by the boldness of his movements, risked, in every campaign, in every battle, the fruits of twenty years of triumph: because his government was so modelled that with him every thing must be swept away, and that a reaction, proportioned to the violence of the action, must burst forth at once both within and without. But Napoleon saw, without illusion, to the bottom of things. The nation, wholly occupied in prosecuting the designs of its chief, had previously not had time to form any plans for itself. The day on which it should have ceased to be stunned by the din of arms, it would have called itself to account for its servile obedience. It is better, thought he, for an absolute prince to fight foreign armies than to have to struggle against the energy of the citizens. Despotism had been organized for making war; war was continued to uphold despotism. The die was cast—France must either conquer Europe, or Europe subdue France. Napoleon fell—he fell, because with the men of the nineteenth century he attempted the work of an Attila and a Genghis Khan; because he gave the reins to an imagination directly contrary to the spirit of his age; with which, nevertheless, his reason was perfectly acquainted; because he would not pause on the day when he felt conscious of his inability to succeed. Nature has fixed a boundary, beyond which extravagant enterprises cannot be carried with prudence. This boundary the Emperor reached in Spain, and overleaped in Russia. Had he then escaped destruction, his inflexible presumption would have caused him to find elsewhere a Bayleu and a Moscow.

General Foy.

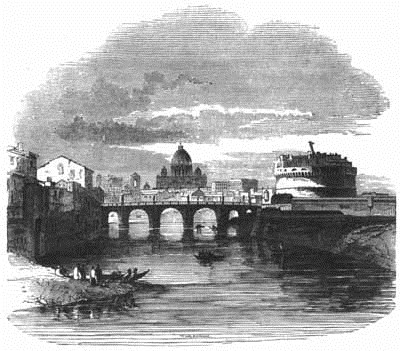

ROME

I am in Rome! Oft as the morning ray

Visits these eyes, waking at once, I cry,

Whence this excess of joy? What has befallen me?

And from within a thrilling voice replies—

Thou art in Rome! A thousand busy thoughts

Rush on my mind—a thousand images;

And I spring up as girt to run a race!

Thou art in Rome! the city that so long

Reign'd absolute—the mistress of the world!

The mighty vision that the Prophet saw

And trembled; that from nothing, from the least,

The lowliest village (what, but here and there

A reed-roof'd cabin by a river side?)

Grew into everything; and, year by year,

Patiently, fearlessly working her way

O'er brook and field, o'er continent and sea;

Not like the merchant with his merchandise,

Or traveller with staff and scrip exploring;

But hand to hand and foot to foot, through hosts,

Through nations numberless in battle array,

Each behind each; each, when the other fell,

Up, and in arms—at length subdued them all.

Thou art in Rome! the city where the Gauls,

Entering at sun-rise through her open gates,

And through her streets silent and desolate

Marching to slay, thought they saw gods, not men;

The city, that by temperance, fortitude,

And love of glory tower'd above the clouds,

Then fell—but, falling, kept the highest seat,

And in her loveliness, her pomp of woe,

Where now she dwells, withdrawn into the wild,

Still o'er the mind maintains, from age to age,

Its empire undiminish'd. There, as though

Grandeur attracted grandeur, are beheld

All things that strike, ennoble; from the depths

Of Egypt, from the classic fields of Greece—

Her groves, her temples—all things that inspire

Wonder, delight! Who would not say the forms.

Most perfect most divine, had by consent

Flock'd thither to abide eternally

Within those silent chambers where they dwell

In happy intercourse?

Rogers.