Various

Appletons' Popular Science Monthly, November 1898

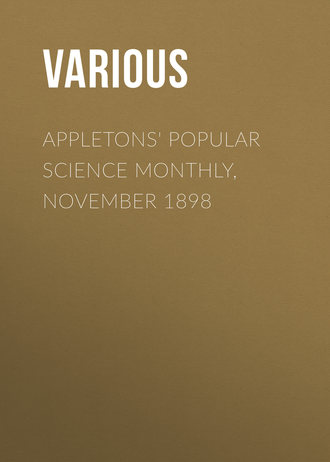

A Florida Sisal Hemp Plant.

Thus far I have only considered spinning fibers. More than one half of the raw fibers imported in the United States are employed in the manufacture of rope and small twine, or bagging for baling the cotton crop. Cordage is manufactured chiefly from the Manila and Sisal hemps, the former derived from the Philippine Islands, the latter from Yucatan. Some jute is also used in this industry, though the fiber is more largely employed in bagging; and some common hemp, such as is grown in Kentucky, is also used.

We can not produce Manila hemp in the United States, and this substance will always hold its own for marine cordage. Jute will grow to perfection in many of the Southern States, but it is doubtful if we can produce it at a price low enough to compete with the cheaper grades of the imported India fiber. Rough flax and common hemp might be used in lieu of jute, in bagging manufacture, but the question of competition is still a factor. Sisal hemp, which has been imported to the value of seven million dollars a year, when prices were high, will grow in southern Florida, and the plant has been the subject of exhaustive study and experiment. This plant was first grown in the United States on Indian Key, Florida, about 1836, a few plants having been introduced from Mexico by Dr. Henry Perrine, and from this early attempt at cultivation the species has spread over southern Florida, the remains of former small experimental tracts being found at many points, though uncared for.

Pineapple Field in Florida.

The high prices of cordage fibers in 1890 and 1891, brought about by the schemes of certain cordage concerns, called attention to the necessity of producing, if possible, a portion of the supply of these hard fibers within our own borders. In 1891, in response to requests for definite information regarding the growth of the Sisal hemp plant, a preliminary survey of the Key system and Biscayne Bay region of southern Florida was made by the Department of Agriculture, and in the following year an experimental factory was established at Cocoanut Grove with special machinery sent down for the work. With this equipment, and with a fast-sailing yacht at the disposal of the special agent in charge of the experiments, a careful study of the Sisal hemp plant, its fiber, and the possibility of the industry was made, and the results were duly published. About this time the Bahaman Government became interested in the industry, and with shiploads of plants, both purchased and gathered without cost on the uninhabited Florida Keys, the Bahamans began the new industry by setting out extensive plantations on the different islands of the group. The high prices of 1890 having overstimulated production in Yucatan, two or three years later there was a tremendous fall in the market price of Sisal hemp, and Florida's interest in the new fiber subsided, though small plantations had been attempted. In the meantime, American invention having continued its efforts in the construction of cleaning devices, two successful machines for preparing the raw fiber have been produced which have, in a measure, superseded the clumsy raspadore hitherto universally employed for the purpose, and one of the obstacles to the production of the fiber in Florida is removed. The reaction toward better prices has already begun, and the future establishment of an American Sisal hemp industry in southern Florida is a possibility, though there are several practical questions yet to be settled.

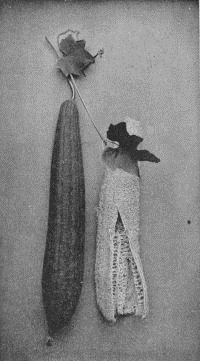

Pineapple culture is already a flourishing industry in the Sisal hemp region. A pineapple plant matures but one apple in a season, and after the harvest of fruit the old leaves are of no further use to the plant, and may be removed. The leaves have the same structural system as the agaves – that is, they are composed of a cellular mass through which the fibers extend, and when the epidermis and pulpy matter are eliminated the residue is a soft, silklike filament, the value of which has long been recognized. Only fifty pounds of this fiber can be obtained from a ton of leaves, but, as the product would doubtless command double the price of Sisal hemp, its production would be profitable. How to secure this fiber cheaply is the problem. The Sisal hemp machines are too rough in action for so fine a fiber, and, at the rate of ten leaves to the pound, working up a ton of the material would mean the handling of over twenty thousand leaves to secure perhaps three dollars' worth of the commercial product. Were the fiber utilized in the arts, however, and its place established, it would compete in a measure with flax as a spinning fiber, for its filaments are divisible to the ten-thousandth of an inch. The substance has already been utilized to a slight extent in Eastern countries (being hand-prepared) in the manufacture of costly, filmy, cobweblike fabrics that will almost float in air.

Another possible fiber industry for Florida is the cultivation of bowstring hemp, or the fiber of a species of Sansevieria that grows in rank luxuriance throughout the subtropical region of the State. The fiber is finer and softer than Sisal hemp, though not so fine as pineapple fiber, and would command in price a figure between the two. The yield is about sixty pounds to the ton of leaves. Many other textile plants might be named that have been experimented with by the Government or through private enterprise, but the most important, in a commercial sense, have been named.

A Plant of New Zealand Flax.

There is a considerable list of plants, however, which are the subject of frequent inquiry, but which will never be utilized commercially as long as other more useful fibers hold the market. These for the most part produce bast fiber, and the farmer knows them as wild field growths or weeds. They are interesting in themselves, and many of them produce a fair quality of fiber, but to what extent they might be brought into cultivation, or how economically the raw material might be prepared, are questions the details of which only experiment can determine. But the fact that at best they can only be regarded as the substitutes for better, already established, commercial fibers has prevented serious experiment to ascertain their place. They are continually brought to notice, however, for again and again the thrifty farmer, as he finds their bleached and weather-beaten filaments clinging to the dead stalks in the fields, deludes himself in believing that he has made a discovery which may lead to untold wealth, and a letter and the specimen are promptly dispatched to the fiber expert for information concerning them. In such cases all that can be done is to give full information, taking care to let the inquirer down as easily as possible.

The limit of practical work in the direction of new textile industries is so clearly defined that the expert need never be in doubt regarding the economic value of any fiber plant that may be submitted to him for an opinion, and the long catalogue of mere fibrous substances will never demand his serious attention.

In studying the problem of the establishment of new fiber industries, therefore, we should consider "materials" rather than particular species of plants – utility or adaptation rather than acclimatization. We should study the entire range of textile manufacture, and before giving attention to questions of cultivation we should first ascertain how far the plants which we already know can be produced within our own borders may be depended upon to supply the "material" adapted to present demands in manufacture. If the larger part of our better fabrics – cordage and fine twines, bagging, and similar rough goods – can be made from cotton, flax, common hemp, and Sisal hemp, which we ought to be able to produce in quantity at home, there is no further need of costly experiments with other fibers. Unfortunately, however, it is possible for manufacturers to "discriminate" against a particular fiber when the use of another fiber better subserves their private interests. As an example, common hemp was discriminated against in a certain form of small cordage, in extensive use, because by employing other, imported fibers, it has been possible in the past to control the supply, and in this day of trusts such control is an important factor in regulating the profits. With common hemp grown on a thousand American farms in 1890, the price of Sisal and Manila hemp binding twine, of which fifty thousand tons were used, would never have been forced up to sixteen and twenty cents a pound, when common hemp, which is just as good for the purpose, could have been produced in unlimited quantity for three and a half cents. The bagging with which the cotton crop is baled is made of imported jute, but common hemp or even low-grade flax would make better bagging. A change from jute to hemp or flax in the manufacture of bagging (it would only be a return to these fibers), could it be brought about, would mean an advantage of at least three million dollars to our farmers. Yet in considering such a desirable change we are confronted with two questions: Is it possible to compete with foreign jute? and can prejudice be overcome? For it is true that there are, even among farmers, those who would hesitate to buy hemp bagging at the same price as jute bagging because it was not the thing they were familiar with. But some of them will buy inferior jute twine, colored to resemble hemp, at the price of hemp, and never question the fraud.

Cabbage Palmetto in Florida.

Our farmers waste the fibrous straw produced on the million acres of flax grown for seed. It has little value, it is true, for the production of good spinning flax, yet by modifying present methods of culture, salable fiber can be produced and the seed saved as well, giving two paying crops from the same harvest where now the flaxseed grower secures but one.

In summarizing the situation in this country, therefore, it will be seen that, out of the hundreds of fibrous plants known to the botanist and to the fiber expert, the textile economist need only consider four or five species and their varieties, all of them supplying well-known commercial products that are regularly quoted in the world's market price current, the cultivation and preparation of which are known quantities. Were the future of new fiber industries in this country to rest upon this simple statement, there would be little need of further effort. The problem, however, is one of economical adaptation to conditions not widely understood in the first place, and not altogether within control in the second.

Twenty flax farmers in a community decide to grow flax for fiber, and two of these farmers are perhaps acquainted with the culture. They go to work each in his own way; ten make a positive failure in cultivation for lack of proper direction, five of the remaining ten fail in retting the straw, and five succeed in turning out as many different grades of flax line, only one grade of which may come up to the standard required by the spinners. And all of them will have lost money. If the failure is investigated it will be discovered that the proper seed was not used; in some instances the soil was not adapted to the culture, and old-fashioned ideas prevailed in the practice followed. The straw was not pulled at the proper time, and it was improperly retted. The breaking and scutching were accomplished in a primitive way, because the farmers could not afford to purchase the necessary machinery, and of course they all lost money, and decided in future to let flax alone.

But the next year the president of the local bank, the secretary of the town board of trade, and three or four prosperous merchants formed a little company and built a flax mill. A competent superintendent – perhaps an old country flax-man – was employed, a quantity of good seed was imported, and the company contracted with these twenty farmers to grow five, ten, or fifteen acres of flax straw each, under the direction of the old Scotch superintendent. The seed was sold to them to be paid for in product; they were advised regarding proper soil and the best practice to follow; they grew good straw, and when it was ready to harvest the company took it off their hands at a stipulated price per ton. The superintendent of the mill assumed all further responsibility, attended to the retting, and worked up the product. Result: several carloads of salable flax fiber shipped to the Eastern market in the winter, the twenty farmers had "money to burn" instead of flax straw, and the company was able to declare a dividend. This is not altogether a supposititious case, and it illustrates the point that in this day of specialties the fiber industry can only be established by co-operation.

The Luffa, or Sponge Cucumber.

In all these industries, whether the fiber cultivated is flax, ramie, or jute, the machine question enters so largely into the problem of their successful establishment that the business must be conducted on a large scale. Even in the growth of Sisal hemp in Florida, should it be attempted, the enterprise will only pay when the necessary mill plant for extracting the fiber is able to draw upon a cultivated area of five hundred acres. In other words, the small farmer can never become a fiber producer independently, but must represent a single wheel in the combination.

The subject is a vast one, and, while I have been able to set forth the importance of these industries as new sources of national prosperity, only an outline has been given of the difficulties which are factors in the industrial problem. Summing up the points of vantage, the market is already assured; through years of study and experiment we are beginning to better understand the particular conditions that influence success or failure in this country; we have the best agricultural implements in the world, and American inventive genius will be able, doubtless, in time, to perfect the new mechanical devices which are so essential to economical production; our farmers are intelligent and industrious, and need only the promise of a fair return for their labor to enter heart and soul into this work.

WHAT IS SOCIAL EVOLUTION?

By HERBERT SPENCER

Though to Mr. Mallock the matter will doubtless seem otherwise, to most it will seem that he is not prudent in returning to the question he has raised; since the result must be to show again how unwarranted is the interpretation he has given of my views. Let me dispose of the personal question before passing to the impersonal one.

He says that I, declining to take any notice of those other passages which he has quoted from me, treat his criticism as though it were "founded exclusively on the particular passage which" I deal with, "or at all events to rest on that passage as its principal foundation and justification."[4] It would be a sufficient reply that in a letter to a newspaper numerous extracts are inadmissible; but there is the further reply that I had his own warrant for regarding the passage in question as conclusively showing the truth of his representations. He writes: —

Should any doubt as to the matter still remain in the reader's mind, it will be dispelled by the quotation of one further passage. "A true social aggregate," he says ["as distinct from a mere large family], is a union of like individuals, independent of one another in parentage, and approximately equal in capacities."[5]

I do not see how, having small liberty of quotation, I could do better than take, as summarizing his meaning, this sentence which he gives as dissipating "any doubt." But now let me repeat the paragraph in which I have pointed out how distorted is Mr. Mallock's interpretation of this sentence.

Every reader will assume that this extract is from some passage treating of human societies. He will be wrong, however. It forms part of a section describing Super-Organic Evolution at large ("Principles of Sociology," sec. 3), and treating, more especially, of the social insects; the purpose of the section being to exclude these from consideration. It is implied that the inquiry about to be entered upon concerns societies formed of like units, and not societies formed of units extremely unlike. It is pointed out that among the Termites there are six unlike forms, and among the Sauba ants, besides the two sexually-developed forms, there are three classes of workers – one indoor and two outdoor. The members of such communities – queens, males, soldiers, workers – differ widely in their structures, instincts, and powers. These communities formed of units extremely unequal in their capacities are contrasted with communities formed of units approximately equal in their capacities – the human communities about to be dealt with. When I thus distinguished between groups of individuals having widely different sets of faculties, and groups of individuals having similar sets of faculties (constituting their common human nature), I never imagined that by speaking of these last as having approximately equal capacities, in contrast with the first as having extremely unequal ones, I might be supposed to deny that any considerable differences existed among these last. Mr. Mallock, however, detaching this passage from its context, represents it as a deliberate characterization to be thereafter taken for granted; and, on the strength of it, ascribes to me the absurd belief that there are no marked superiorities and inferiorities among men! or, that if there are, no social results flow from them![6]

Though I thought it well thus to repudiate the absurd belief ascribed to me, I did not think it well to enter upon a discussion of Mr. Mallock's allegations at large. He says I ought to have given to the matter "more than the partial and inconclusive attention he has [I have] bestowed upon it." Apparently he forgets that if a writer on many subjects deals in full with all who challenge his conclusions, he will have time for nothing else; and he forgets that one who, at the close of life, has but a small remnant of energy left, while some things of moment remain to be done, must as a rule leave assailants unanswered or fail in his more important aims. Now, however, that Mr. Mallock has widely diffused his misinterpretations, I feel obliged, much to my regret, to deal with them. He will find that my reply does not consist merely of a repudiation of the absurdity he ascribes to me.

The title of his book is a misnomer. I do not refer to the fact that the word "Aristocracy," though used in a legitimate sense, is used in a sense so unlike that now current as to be misleading: that is patent. Nor do I refer to the fact that the word "Evolution," covering, as it does, all orders of phenomena, is wrongly used when it is applied to that single group of phenomena constituting Social Evolution. But I refer to the fact that his book does not concern Social Evolution at all: it concerns social life, social activity, social prosperity. Its facts bear somewhat the same relation to the facts of Social Evolution as an account of a man's nutrition and physical welfare bears to an account of his bodily structure and functions.

In an essay on "Progress: its Law and Cause," published in 1857, containing an outline of the doctrine which I have since elaborated in the ten volumes of Synthetic Philosophy, I commenced by pointing out defects in the current conception of progress.

It takes in not so much the reality of Progress as its accompaniments – not so much the substance as the shadow. That progress in intelligence seen during the growth of the child into the man, or the savage into the philosopher, is commonly regarded as consisting in the greater number of facts known and laws understood: whereas the actual progress consists in those internal modifications of which this increased knowledge is the expression. Social progress is supposed to consist in the produce of a greater quantity and variety of the articles required for satisfying men's wants; in the increasing security of person and property; in widening freedom of action: whereas, rightly understood, social progress consists in those changes of structure in the social organism which have entailed these consequences. The current conception is a teleological one. The phenomena are contemplated solely as bearing on human happiness. Only those changes are held to constitute progress which directly or indirectly tend to heighten human happiness. And they are thought to constitute progress simply because they tend to heighten human happiness. But rightly to understand progress, we must inquire what is the nature of these changes, considered apart from our interests.[7]

With the view of excluding these anthropocentric interpretations and also because it served better to cover those inorganic changes which the word "progress" suggests but vaguely, I employed the word "evolution." But my hope that, by the use of this word, irrelevant facts and considerations would be set aside, proves ill-grounded. Mr. Mallock now includes under it those things which I endeavored to exclude. He is dominated by the current idea of progress as a process of improvement, in the human sense; and is thus led to join with those social changes which constitute advance in social organization, those social changes which are ancillary to it – not constituting parts of the advance itself, but yielding fit materials and conditions. It is true that he recognizes social science as aiming "to deduce our civilization of to-day from the condition of the primitive savage." It is true that he says social science "primarily sets itself to explain, not how a given set of social conditions affects those who live among them, but how social conditions at one epoch are different from those of another, how each set of conditions is the resultant of those preceding it."[8] But in his conception as thus indicated he masses together not the phenomena of developing social structures and functions only, but all those which accompany them; as is shown by the complaint he approvingly cites that the sociological theory set forth by me does not yield manifest solutions of current social problems:[9] clearly implying the belief that an account of social evolution containing no lessons which he who runs may read is erroneous.

While Mr. Mallock's statements and arguments thus recognize Social Evolution in a general way, and its continuity with evolution of simpler kinds, they do not recognize that definition of evolution under its various forms, social included, which it has been all along my purpose to illustrate in detail. He refers to evolution as exhibited in the change from a savage to a civilized state; but he does not ask in what the change essentially consists, and, not asking this, does not see what alone is to be included in an account of it. Let us contemplate for a moment the two extremes of the process.

Here is a wandering cluster of men, or rather of families, concerning which, considered as an aggregate, little more can be said than can be said of a transitory crowd: the group considered as a whole is to be described not so much by characters as by the absence of characters. It is so loose as hardly to constitute an aggregate, and it is practically structureless. Turn now to a civilized society. No longer a small wandering group but a vast stationary nation, it presents us with a multitude of parts which, though separate in various degrees, are tied together by their mutual dependence. The cluster of families forming a primitive tribe separates with impunity: now increase of size, now dissension, now need for finding food, causes it from time to time to divide; and the resulting smaller clusters carry on what social life they have just as readily as before. But it is otherwise with a developed society. Not only by its stationariness is this prevented from dividing bodily, but its parts, though distinct, have become so closely connected that they can not live without mutual aid. It is impossible for the agricultural community to carry on its business if it has not the clothing which the manufacturing community furnishes. Without fires neither urban nor rural populations can do their work, any more than can the multitudinous manufacturers who need engines and furnaces; so that these are all dependent on coal-miners. The tasks of the mason and the builder must be left undone unless the quarryman and the carpenter have been active. Throughout all towns and villages retail traders obtain from the Manchester district the calicoes they want, from Leeds their woolens, from Sheffield their cutlery. And so throughout, in general and in detail. That is to say, the whole nation is made coherent by the dependence of its parts on one another – a dependence so great that an extensive strike of coal-miners checks the production of iron, throws many thousands of ship-builders out of work, adds to the outlay for coal in all households, and diminishes railway dividends. Here then is one primary contrast – the primitive tribe is incoherent, the civilized nation is coherent.

While the developing society has thus become integrated, it has passed from its original uniform state into a multiform state. Among savages there are no unlikenesses of occupations. Every man is hunter and upon occasion warrior; every man builds his own hut, makes his own weapons; every wife digs roots, catches fish, and carries the household goods when a change of locality is needed: what division of labor exists is only between the sexes. We all know that it is quite otherwise with a civilized nation. The changes which have produced the coherence have done this by producing the division of labor: the two going on pari passu. The great parts and the small parts, and the parts within parts, into which a modern society is divisible, are clusters of men made unlike in so far as they discharge the unlike functions required for maintaining the national life. Rural laborers and farmers, manufacturers and their workpeople, wholesale merchants and retailers, etc., etc., constitute differentiated groups, which make a society as a whole extremely various in composition. Not only in its industrial divisions is it various, but also in its governmental divisions, from the components of the legislature down through the numerous kinds and grades of officials, down through the many classes of masters and subordinates, down through the relations of shopkeeper and journeyman, mistress and maid. That is to say, the change which has been taking place is, under one aspect, a change from homogeneity of the parts to heterogeneity of the parts.

A concomitant change has been from a state of vague structure, so far as there is any, to a state of distinct structure. Even the primary differentiation in the lowest human groups is confused and unsettled. The aboriginal chief, merely a superior warrior, is a chief only while war lasts – loses all distinction and power when war ceases; and even when he becomes a settled chief, he is still so little marked off from the rest that he carries on his hut-building, tool-making, fishing, etc., just as the rest do. In such organization as exists nothing is distinguished, everything is confused. Quite otherwise is it in the developed nation. The various occupations, at the same time that they have become multitudinous, have become clearly specialized and sharply limited. Read the London Directory, and while shown how numerous they are, you are shown by the names how distinct they are. This increasing distinctness has been shown from the early stages when all freemen were warriors, through the days when retainers now fought and now tilled their fields, down to the times of standing armies; or again from the recent days when in each rural household, besides the bread-winning occupation, there were carried on spinning, brewing, washing, to the present day when these several supplementary occupations have been deputed to separate classes exclusively devoted to them. It has been shown from the ages when guilds quarreled about the things included in their respective few businesses, down to our age when the many businesses of artisans are fenced round and disputed over if transgressed, as lately by boilermakers and fitters; and is again shown by the ways in which the professions – medical, legal, and other – form themselves into bodies which shut out from practice, if they can, all who do not bear their stamp. And throughout the governmental organization, from its first stage in which the same man played various parts – legislative, executive, judicial, militant, ecclesiastic – to late stages when the powers and functions of the multitudinous classes of officials are clearly prescribed, may be traced this increasing sharpness of division among the component parts of a society. That is to say, there has been a change from the indefinite to the definite. While the social organization has advanced in coherence and heterogeneity, it has also advanced in definiteness.

If, now, Mr. Mallock will turn to First Principles, he will there see that under its chief aspect Evolution is said to be a change from a state of indefinite, incoherent homogeneity to a state of definite, coherent heterogeneity. If he reads further on he will find that these several traits of evolution are successively exemplified throughout astronomic changes, geologic changes, the changes displayed by each organism, by the aggregate of all organisms, by the development of the mental powers, by the genesis of societies, and by the various products of social life – language, science, art, etc. If he pursues the inquiry he will see that in the series of treatises (from which astronomy and geology were for brevity's sake omitted) dealing with biology, psychology, and sociology, the purpose has been to elaborate the interpretations sketched out in First Principles; and that I have not been concerned in any of them to do more than delineate those changes of structure and function which, according to the definition, constitute Evolution. He will see that in treating of social evolution I have dealt only with the transformation through which the primitive small social germ has passed into the vast highly developed nation. And perhaps he will then see that those which he regards as all-important factors are but incidentally referred to by me because they are but unimportant factors in this process of transformation. The agencies which he emphasizes, and in one sense rightly emphasizes, are not agencies by which the development of structures and functions has been effected; they are only agencies by which social life has been facilitated and exalted, and aids furnished for further social evolution.