Фредерик Марриет

Diary in America, Series Two

Their principal argument raised against the copyright, is as follows:—

“It is only by the enlightening and education of the people, that we can expect our institutions to hold together. You ask us to tax ourselves, to check the circulation of cheap literature, so essential to our welfare for the benefit of a few English authors? Are the interests of thirteen millions of people to be sacrificed? the foundation of our government and institutions to be shaken for such trivial advantages as would be derived by a few foreign authors. Your claim has the show of justice we admit, but when the sacrifice to justice must be attended with such serious consequences, must we not adhere to expediency?”

Now, it so happens that the very reverse of this argument has always proved to be the case from the denial of copyright. The enlightening of a people can only be produced by their hearing the truth, which they cannot, and do not, under existing regulations, receive from their own authors, as I have already pointed out; and the effects of their refusal of the copyright to English authors, is, that the American publishers will only send forth such works as are likely to have an immediate sale, such as the novels of the day, which may be said at present to comprise nearly the whole of American rending. Such works as might enlighten the Americans are not so rapidly saleable as to induce an American publisher to risk publishing when there is such competition. What is the consequence that the Americans are amused, but not instructed or enlightened?

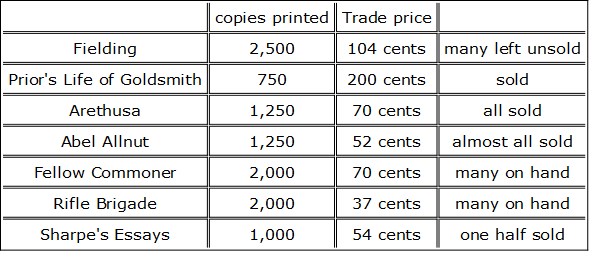

According to the present system of publication in America, the grant of copyright would prove to be of advantage only to a few authors—of course, I refer to the most popular. I had free admission to the books of one of the largest publishing houses in the United States, and I extracted from them the profits received by this house for works of a certain reputation. It will be perceived, that the editions published are not large. The profits of the American houses chiefly resulting from the number of works published, each of these yielding a moderate profit, which when collected together, swell into a large sum total.

Now, as there are one hundred cents to a dollar, and the expenses of printing, paper, and advertising have to be deducted, as well as the copies left on hand, it will be evident, that the profit on each of the above works, would be too small to allow the publishers in America to give even 20 pounds for the copyright, the consequence of a copyright would therefore be, that the major portion of the works printed would not be published at all, and better works would be substituted. Of course, such authors as Walter Scott, Byron, Bulwer, etcetera, have a most extensive sale; and the profits are in proportion, but then it must be remembered that a great many booksellers publish editions, and the profits are divided accordingly. Could Sir Walter Scott have obtained a copyright in the United States, it would have bean worth to him by this time at least 100,000 pounds.

The Americans talk so much about their being the most enlightened nation in the world, that it has been generally received to be the case. I have already stated my ideas on this subject, and I think that the small editions usually published, of works not standard or elementary, prove, that with the exception of newspapers, they are not a reading nation. The fact is, they have no time to read; they are all at work; and if they get through their daily newspaper, is quite as much as most of them can effect. Previous to my arrival in the United States, and even for some time afterwards, I had an idea that there was a much larger circulation of every class of writing in America, than there really is. It is only the most popular English authors, as Walter Scott, or the most fashionable, as Byron, which have any extensive circulation; the works which at present the Americans like best, are those of fiction in which there is anything to excite or amuse them, which is very natural, considering how actively they are employed during the major portion of their existence, and the consequent necessity of occasional relaxation. When we consider the extreme cheapness of books in the United States, and the enormous price of them in this country, the facilities of reading them there, and the difficulty attending it here from the above cause, I have no hesitation in saying, that as a reading nation, the United States cannot enter into comparison with us.

As I am upon this subject, I cannot refrain from making a few remarks upon it, as connected with this country. The price of a book now published is enormous, when the prime cost of paper and printing is considered; the actual value of each three volumes of a moderate edition, which are sold at a guinea and a half, being about four shillings and sixpence, and when the edition is large, as the outlay for putting up the type is the same in both, of course it is even less; but the author must be paid, and upon the present small editions he adds considerably to the price charged upon every volume; then comes the expense of advertising, which is very heavy; the profits of the publisher, and the profits of the trade in general; for every book for which the public pay a guinea and a half, is delivered by the publisher to the trade, that is, to the booksellers, at 1 pound 1 shillings 3 pence. The allowance to the trade, therefore, is the heaviest tax of all; but it is impossible for booksellers to keep establishments, clerks, etcetera, without having indemnification. In all the above items, which so swells up the price of the book, there cannot well be any deduction made.

Let us examine into the division of profits. I am only making an approximation, but it is quite near enough for the purpose.

An edition of 1,000 copies at 1 pound 11 shillings 6 pence will give 1,575 pounds.

Positive Expenses to Publisher

Trade allowance of 10 shillings. 3 pence per copy: 512 pounds 10 shillings.

Extra allowance. 25 for 24-40 copies: 63 pounds.

Printing and paper, 4 shillings 6 pence per copy: 225 pounds 0 shillings.

Advertising, equal to 2 shillings per copy: 100 pounds 0 shillings.

Presentations to Universities and Reviewers, say 30 copies: 47 pounds 5 shillings.

The author if he is well known, may be said to receive 7 shillings per copy: 250 pounds 0 shillings.

Leaving for the publisher: 277 pounds 0 shillings.

Total 1,575 pounds 0 shillings.

All the first expenses being positive, it follows that the struggle is between the publisher and the author, as to what division shall be made of the remainder. The publisher points out the risk he incurs, and the author his time and necessities; and when it is considered that many authors take more than a year to write a book, it must be acknowledged that the sum paid to them, as I have put it down, is not too great. The risk, however, is with the publisher, and the great profits with the trade, which is perhaps the reason why booksellers often make fortunes, and publishers as often become bankrupts. Generally speaking, however, the two are combined, the sure gain of the bookseller being as a set off against the speculation of the publisher.

But one thing is certain, the price of books in this country is much too high, and what are the consequences? First, that instead of purchasing books, and putting them into their libraries, people have now formed themselves into societies and book-clubs, or trust entirely to obtaining them from circulating libraries. Without a book is very popular, it is known by the publisher what the sale is likely to be, within perhaps fifty copies; for the book-clubs and libraries will, and must have it, and hardly anybody else will; for who will pay a guinea and a half for a book which may, after all, prove not worth reading! Secondly, it has the effect of the works being reprinted abroad, and sent over to this country; which, of course, decreases the sale of the English edition. At the Custom-House, they now admit English works printed in Paris, at a small duty, when brought over in a person’s luggage for private reading; and these foreign editions are smuggled, and are to be openly purchased at most of the towns along the coast. This cannot be prevented—and as for any international copyright being granted by France or Belgium, I do not think that it ever will be; and if it were, it would be of no avail, for the pirating would then be carried on a little further off in the small German States; and if you drove it to China, it would take place there. We are running after a Will-o’-the-wisp in that expectation. The fault lies in ourselves; the books are too dear, and the question now is, cannot they be made cheaper?

There is a luxury in printing, to which the English have been so long accustomed, that it would not do to deprive them of it. Besides, bad paper and bad type would make but little difference in the expense of the book, as my calculation will show; but if a three volume work14 could be delivered to the public at ten shillings, instead of a guinea and a half, it would not only put a stop to piracy abroad, but the reduced price would induce many hundreds to put it into their library, and be independent of the hurried reading against time, and often against inclination, to which they are subject by book-clubs and circulating libraries; and that this is not the case, is the fault of the public itself, and not of the author, publisher, or any other party.

It is evident that the only way by which books may be made cheap, is by an extended sale—and “Nicholas Nickleby”, and other works of that description, have proved that a cheap work will have an extended sale—always provided it is a really good one.

But it is impossible to break through the present arrangements which confine the sale of books, unless the public themselves will take it in hand—if they choose to exert themselves, the low prices may be firmly established with equal benefit to all parties, and with an immense increase in the consumption of paper. To prove that any attempt on the part of an author or publisher will not succeed unaided, it was but a few months ago, that Mr Bentley made the trial, and published the three volumes at one guinea; but he did not sell one copy more—the clubs and libraries took the usual number, and he was compelled to raise his price. The rapid sale of the Standard Novels, which have been read over and over again, when published at the price of five shillings, is another proof that the public has no objection to purchase when the price is within its means.

I can see but one way by which this great desideratum is to be effected; which is, by the public insuring by subscription any publisher or bookseller from loss, provided he delivers the works at the reduced price. At present, one copy of a book may be said to serve for thirty people at least; but say that it serves for ten, or rather say that you could obtain five thousand, or even a less number, of people to put down their names as subscribers to all new works written by certain named authors, which should be published at the reduced price of ten shillings per copy. Let us see the result.

A ten shilling work under such auspices would be delivered to the trade at eight shillings.

The value of the five thousand copies to the publisher would be 2,000 shillings 0 shillings.

The expenses of printing and paper would be reduced to about 3 shillings a copy, which would be 750 pounds.

Advertising, as before, 100 pounds.

Extra 1 shilling 3 pence, 4 shillings, 5 shillings, about 16 pounds, subtotal 866 pounds.

Leaving a profit for author and publisher of 1,134 pounds 0 shillings.

Whereas, in the printing of a thousand copies, the profits of author 350 pounds, and of publisher 277 pounds 5 shillings, equalled only 627 pounds 5 shillings.

Extra profit to author and publisher 506 pounds 15 shillings.

Here the public would gain, the author would gain, and the publisher would gain; nor would any party lose; the profits of the trade would not be quite so great, being 500 pounds, instead of 575 pounds; but it must be remembered, that there are many who, not being subscribers, would purchase the book as soon as they found that it was approved of—indeed, there is no saying to what extent the sale might prove to be.

If any one publisher sold books at this price, the effect would be of reducing the price of all publications, for either the authors must apply to the cheap publisher, or the other publishers sell at the same rate, or they would not sell at all. Book-clubs and circulating libraries would then rapidly break up, and we should obtain the great desideratum of cheap literature.

And now that I have made my statement, what will be the consequence? Why, people will say, “that’s all very well, all very true”—and nobody will take the trouble—the consequence is, that the public will go on, paying through the nose as before—and if so, let it not grumble; as it has no one to thank but itself for it.15

The paper and printing in America is, generally speaking, so very inferior, that the books are really not worth binding, and are torn up or thrown away after they are read—not that they cannot print well; for at Boston particularly they turn out very excellent workmanship. Mr Prescott’s “Ferdinand and Isabella”, is a very good specimen, and so are many of the Bibles and Prayer books. In consequence of their own bad printing, and the tax upon English books, there are very few libraries in America: and in this point, the American government should make some alteration, as it will be beneficial to both countries. The English editions, if sent over, would not interfere with the sale of their cheap editions, and it would enable the American gentlemen to collect libraries. The duty, at present, is twenty-six cents per pound, on books in boards, and thirty cents upon bound-books.

Now, with the exception of school books, upon which the duty should be retained, this duty should be very much reduced.

At present, all books published prior to 1775, are admitted upon a reduced duty of five cents. This date should be extended to 1810, or 1815, and illustrated works should also be admitted upon the reduced duty. It would be a bonus to the Americans who wish to have libraries, and some advantage to the English booksellers.

I cannot dismiss this subject without pointing out a most dishonest practice, which has latterly been resorted to in the United States, and which a copyright only, I am afraid, can prevent the continuance of. Works which have become standard authority in England, on account of the purity of their Christian principles, are republished in America with whole pages altered, advantage being taken of the great reputation of the orthodox writers, to disseminate Unitarian and Socinian principles. A friend of mine, residing in Halifax, Nova Scotia, sent to a religious book society at New York for a number of works, as presents to the children attending the Sunday school. He did not examine them, having before read the works in England, and well knowing what ought to have been the contents of each.

To his surprise, the parents came to him a few days afterwards to return the books, stating that they presumed that he could not be aware of the nature of their contents; and on examination, he found that he had been circulating Unitarian principles among the children, instead of those which he had wished to inculcate.16

The press of America, as I have described it, is all powerful; but still it must be borne in mind, that it is but the slave of the majority; which, in its turn, it dare not oppose.

Such is its tyranny, that it is the dread of the whole community. No one can—no one dare—oppose it; whosoever falls under its displeasure, be he as innocent and as pure as man can be, his doom is sealed. But this power is only delegated by the will of the majority, for let any author in America oppose that will, and he is denounced. You must drink, you must write, not according to your own opinions, or your own thoughts, but as the majority will.17

Mr Tocqueville observes, “I know no country in which there is so little true independence of mind, and freedom of discussion, as in America.”

Volume One—Chapter Eight

The Mississippi

I have headed this chapter with the name of the river which flows between the principal States in which the society I am about to depict is to be found; but, at the same time, there are other southern States, such as Alabama and Georgia, which must be included. I shall attempt to draw the line as clearly as I can, for although the territory comprehended is enormous, the population is not one-third of that of the United States, and it would be a great injustice if the description of the society I am about to enter into should be supposed to refer to that of the States in general. It is indeed most peculiar, and arising frow circumstances which will induce me to refer back, that the causes may be explained to the reader. Never, perhaps, in the records of nations was there an instance of a century of such unvarying and unmitigated crime as is to be collected from the history of the turbulent and blood-stained Mississippi. The stream itself appears as if appropriate for the deeds which have been committed. It is not like most rivers, beautiful to the sight, bestowing fertility in its course; not one that the eye loves to dwell upon as it sweeps along, nor can you wander on its bank, or trust yourself without danger to its stream. It is a furious, rapid, desolating torrent, loaded with alluvial soil; and few of those who are received into its waters ever rise again, or can support themselves long on its surface without assistance from some friendly log. It contains the coarsest and most uneatable of fish, such as the cat-fish and such genus, and, as you descend, its banks are occupied with the fetid alligator, while the panther basks at its edge in the cane-brakes, almost impervious to man. Pouring its impetuous waters through wild tracks, covered with trees of little value except for firewood, it sweeps down whole forests in its course, which disappear in tumultuous confusion, whirled away by the stream now loaded with the masses of soil which nourished their roots, often blocking up and changing for a time the channel of the river, which, as if in anger at its being opposed, inundates and devastates the whole country round; and as soon as it forces its way through its former channel, plants in every direction the uprooted monarchs of the forest (upon whose branches the bird will never again perch, or the racoon, the opossum or the squirrel, climb) as traps to the adventurous navigators of its waters by steam, who, borne down upon these concealed dangers which pierce through the planks, very often have not time to steer for and gain the shore before they sink to the bottom. There are no pleasing associations connected with the great common sewer of the western America, which pours out its mud into the Mexican Gulf, polluting the clear blue sea for many miles beyond its mouth. It is a river of desolation; and instead of reminding you, like other beautiful rivers, of an angel which has descended for the benefit of man, you imagine it a devil, whose energies have been only overcome by the wonderful power of steam.

The early history of the Mississippi is one of piracy and buccaneering; its mouths were frequented by these marauders, as in the bayous and creeks they found protection and concealment for themselves and their ill-gotten wealth. Even until after the war of 1814 these sea-robbers still to a certain extent flourished, and the name of Lafitte, the last of their leaders, is deservedly renowned for courage and for crime; his vessels were usually secreted in the land-locked bay of Barataria, to the westward of the mouth of the river. They were, however, soon extirpated by the American government. The language of the adjacent States is still adulterated with the slang of those scoundrels, proving how short a period it is since they disappeared, and how they must have mixed up with the reckless population, whose head-quarters were then at the mouth of the river.

But as the hunting-grounds of Western Virginia, Kentucky, and the northern banks of the Ohio, were gradually wrested from the Shawnee Indians, the population became more dense, and the Mississippi itself became the means of communication and of barter with the more northern tribes. Then another race of men made their appearance, and flourished for half a century, varying indeed in employment, but in other respects little better than the buccaneers and pirates, in whose ranks they were probably first enlisted. These were the boatmen of the Mississippi, who with incredible fatigue forced their “keels” with poles against the current, working against the stream with the cargoes entrusted to their care by the merchants of New Orleans, labouring for many months before they arrive at their destination, and returning with the rapid current in as many days as it required weeks for them to ascend. This was a service of great danger and difficulty, requiring men of iron frame and undaunted resolution: they had to contend not only with the stream, but, when they ascended the Ohio, with the Indians, who, taking up the most favourable positions, either poured down the contents of their rifles into the boat as she passed; or, taking advantage of the dense fog, boarded them in their canoes, indiscriminate slaughter being the invariable result of the boatmen having allowed themselves to be surprised. In these men was to be found, as there often is in the most unprincipled, one redeeming quality (independent of courage and perseverance), which was, that they were, generally speaking, unscrupulously honest to their employers, although they made little ceremony of appropriating to their own use the property, or, if necessary, of taking the life any other parties. Wild, indeed, are the stories which are still remembered of the deeds of courage, and also of the fearful crimes committed by these men, on a river which never gives up its dead. I say still remembered, for in a new country they readily forget the past, and only look forward to the future, whereas in an old country the case is nearly the reverse—we love to recur to tradition, and luxuriate in the dim records of history.

The following description of the employment of this class of people is from the pen of an anonymous American author:—

“There is something inexplicable in the fact, there could be men found, for ordinary wages, who would abandon the systematic but not laborious pursuits of agriculture to follow a life, of all others except that of the soldier, distinguished by the greatest exposure and privation. The occupation of a boatman was more calculated to destroy the constitution and to shorten life than any other business. In ascending the river it was a continued series of toil, rendered more irksome by the snail-like rate at which they moved. The boat was propelled by poles, against which the shoulder was placed, and the whole strength and skill of the individual were applied in this manner. As the boatmen moved along the running board, with their heads nearly touching the plank on which they walked, the effect produced on the mind of an observer was similar to that on beholding the ox rocking before an overloaded cart. Their bodies, naked to their waist for the purpose of moving with greater ease and of enjoying the breeze of the river, were exposed to the burning suns of summer and to the rains of autumn. After a hard day’s push they would take their ‘fillee,’ or ration of whisky, and, having swallowed a miserable supper of meat half burnt, and of bread half baked, stretched themselves, without covering, on the deck, and slumber till the steersman’s call invited them to the morning ‘fillee.’ Notwithstanding this, the boatman’s life had charms as irresistible as those presented by the splendid illusions of the stage. Sons abandoned the comfortable farms of their fathers, and apprentices fled from the service of their masters. There was a captivation in the idea of ‘going down the river,’ and the ‘youthful boatman who had pushed a keel’ from New Orleans felt all the pride of a young merchant after his first voyage to an English sea-port. From an exclusive association together they had formed a kind of slang peculiar to themselves; and from the constant exercise of wit with the squatters on shore, and crews of other boats, they acquired a quickness and smartness of vulgar retort that was quite amusing. The frequent battles they were engaged in with the boatmen of different parts of the river, and with the less civilised inhabitants of the lower Ohio and Mississippi, invested them with that furious reputation which has made them spoken of throughout Europe.

“On board of the boats thus navigated our merchants entrusted valuable cargoes, without insurance, and with no other guarantee than the receipt of the steersman, who possessed no property but his boat; and the confidence so reposed was seldom abused.”

Every class of men has its hero, as those always will be, who, from energy of character and natural endowment, are superior to their fellows. The most remarkable person among these people was one Mike Fink, who was their acknowledged leader for many years. His fame was established from New Orleans to Pittsburg. He was endowed with gigantic strength, courage, and presence of mind—his rifle was unerring, and his conscience never troubled his repose. Every one was afraid of him; every one was anxious to be on good terms with him, for he was a regular freebooter; and although he spared his friends, he gave no quarter to the lives or properties of others. Mike Fink was not originally a boatmen: at an early age he had enlisted in the company of scouts, another variety of employment produced by circumstances—a species of solitary rangers employed by the American government, and acting as spies, to watch the motions of the Indians on the frontiers. This peculiar service is thus described by the author I have before quoted:—

“At that time, Pittsburg was on the extreme verge of white population, and the spies, who were constantly employed, generally extended their reconnaissance forty or fifty miles to the west of this post. They went out singly, lived as did the Indian, and in every respect became perfectly assimilated in habits, taste, and feeling, with the red men of the desert. A kind of border warfare was kept up, and the scout thought it as praiseworthy to bring in the scalp of a Shawnee, as the skin of a panther. He would remain in the woods for weeks together, using parched corn for bread, and depending on his rifle for his meat—and slept at night in perfect comfort, rolled in his blanket.”

In this service Mike Fink acquired a great reputation for coolness and courage, and many are the stories told of his adventures with the Indians. It has been incontestably proved, that the white man, when accustomed to the woods, is much more acute than the Indian himself in that woodcraft of every species, in which the Indian is supposed to be such an adept; such as discovering a trail by the print of a mocassin, by the breaking of twigs, laying of the grass, etcetera, and in the practice of the rifle he is very superior. As a proof of Fink’s dexterity with his rifle, he is said one day, as they were descending the Ohio in their boat, to have laid a wager, and won it, that he would from mid-stream with his rifle balls cut off at the stumps the tails of five pigs which were feeding on the banks. One story relative to Mike Fink, when he was employed as a scout, will be interesting to the reader.

“As he was creeping along one morning, with the stealthy tread of a cat, his eye fell upon a beautiful buck browsing on the edge of a barren spot, three hundred yards distant. The temptation was too strong for the woodsman, and he resolved to have a shot at every hazard. Repriming his gun, and picking his flint, he made his approaches in the usual noiseless manner. But the moment he reached the spot from which he meant to take his aim, he observed a large savage, intent upon the same object, advancing from a direction a little different from his own. Mike shrunk behind a tree with the quickness of thought, and keeping his eye fixed on the hunter, waited the result with patience. In a few moments the Indian halted within fifty paces, and levelled his piece at the deer. In the meanwhile Mike presented his rifle at the body of the savage, and at the moment the smoke issued from the gun of the latter, the bullet of Fink passed through the red man’s breast. He uttered a yell, and fell dead at the same instant with the deer. Mike re-loaded his rifle, and remained in his covert for some minutes to ascertain whether there were more enemies at hand. He then stepped up to the prostrate savage, and having satisfied himself that life was extinguished, turned his attention to the buck, and took from the carcase those pieces suited to the process of jerking.”

As the country filled up the Indians retreated, and the corps of scouts was abolished: but after a life of excitement in the woods, they were unfitted for a settled occupation. Some of them joined the Indians, others, and among them Mike Finn, enrolled themselves among the fraternity of boatmen on the Mississippi.

The death of Mike Fink was befitting his life. One of his very common exploits with his rifle was hitting for a wager, at thirty yards distance, a small tin pot, used by the boatmen, which was put on the head of another man. Such was his reputation, that no one hardly objected to being placed in this precarious situation. It is even said that his wife, that is, his Mississippi wife, was accustomed to stand the fire; this feat was always performed for a wager of a quart of spirits, made by some stranger, and was a source of obtaining the necessary supplies. One day the wager was made as usual, and a man with whom Mike had at one time been at variance (although the feud was now supposed to have been forgotten) was the party who consented that the pot should be placed on his head. Whether it was that Mike was not quite sober, or that he retained his ill-will towards the man, certain it is, that in this instance, instead of his hitting the mark, his bullet went below it and through the brain of the man, who instantly fell dead; but his brother, who was standing by, and probably suspecting treachery, had his loaded rifle in his hand, levelled, fired, and in a second the soul of Mike was despatched after that of his victim.