Baring-Gould Sabine

Cornish Characters and Strange Events

THOMASINE BONAVENTURA

Week S. Mary stands in a treeless wind-swept situation, 530 feet above the sea, near the source of two small streams rising in the desolate downs to the south, which unite their waters at Langford, and have sawn for themselves deep clefts that are well wooded. At a remote period this district must have been the scene of contests, for it is studded with earthworks. There was a castle at Week, but camps also crowning a height in Westwood and in Swannacott Wood; and Week S. Mary with its castle stood aloft, defended by one of these on each side. Formerly there was not so much enclosed land as there is at present; but it was precisely the moorland that extended over so large a portion of the parish that constituted its wealth, for on this waste pastured vast flocks of sheep, whose fleeces were in request at a time when wool was the staple industry in the West of England.

The ridge of bare, uplifted, carboniferous rock and clay, cold and bleak, was formerly scantily provided with roads, and with homesteads few and far between; and to guide the traveller through the waste, certain churches with lofty towers were erected on high ground – Pancrasweek, Holsworthy, Bridgerule, Week S. Mary – to enable him to make his way across country from one to the other. A farm or a manor-house nestled in a combe, sheltered from the wind, from the sea, and the driving rain; but farmer and squire drew their wealth from the sheep on the uplands, which were moreover strewn, as they still are, with barrows, under which lie the dead of the Bronze and Stone ages.

Davies Gilbert absurdly derives the name of the place from the Cornish, and makes it signify "sweet." No more unsuitable epithet could have been applied. It signifies vicus, a village or hamlet, and is found also at Pancrasweek, Germansweek, and elsewhere.

In the village are still to be seen the remains of the old school and chantry founded by Thomasine Bonaventura, a shepherd girl, native of the place, whose story is told by Carew and by Hall; and from them we take it.

Thomasine was born about the year 1450, in the reign of Henry VI, and her father was a small farmer who had his flock of sheep pasturing on the wild waste common-lands. Thomasine watched it, and spun from her distaff. Above the desolate moors to the south-west stood up blue against the sky the rugged height of Brown Willy, crowned by its mighty cairns; to the west and south-west stretched the Atlantic, into which the evening sun went down in a blaze of glory.

One day a London merchant, a dealer in wool, came riding over the moor; probably from Tintagel or Forrabury, and making direct for Week S. Mary tower, when he passed a barrow on which sat the shepherd girl spinning, the breeze from the sea blowing her dark hair about, singing some old ballad, but ever keeping her eye on her father's sheep. Behind him trailed a line of horses laden with the packs of wool that he had purchased, led by his men. He halted to speak to the girl, probably to learn from her where he might best ford the stream in the valley below. She answered, and he was pleased with her intelligence, and not less with her beauty. He inquired who she was, what was her name, and what the circumstances of her parents. To all these questions she gave prompt and direct answers. Then, still more taken with her, he asked Thomasine whether she would accompany him to London, to be servant to his wife, and he offered her good wages and kind treatment. She replied, with caution, that she was under the guardianship of her father and mother, and that she could not accept his proposal without their consent.

Thereupon the merchant rode on, and upon reaching Week S. Mary inquired for the house of the parents of Thomasine and laid his offer before them. When they hesitated, he referred them to his customers.

The parents, no doubt, were highly elated at being able to get their daughter into a situation in London, where all the streets were paved with gold. But it may well be doubted whether they dreamt of what was in store for her.

So she parted from her parents, certainly with many tears on her part, and earnest injunctions from father and mother to conduct herself in a modest and obedient manner.

Now these wool merchants and clothiers were men of mighty repute and good substance in the land. In Thomas Deloney's delightful Pleasant Historie of Thomas of Reading, 1600, we read: "Among all crafts this was the onely chiefe, for that it was the chiefest merchandize, by the which our Country became famous throwout all Nations. And it was verily thought that the one halfe of the people in the land lived in those dayes thereby, and in such good sort, that in the Commonwealth there were few or no beggars at all: poore people, whom God lightly blessed with most children, did by meanes of this occupation so order them, that by the time that they were come to be sixe or seven yeares of age, they were able to get their owne bread. Idlenesse was then banished our coast, so that it was a rare thing to heare of a thiefe in those dayes. Therefore it was not without cause that Clothiers were then both honoured and loved."

Doubtless so soon as the merchant reached Launceston he placed all the wool he purchased on carts, to convey it to town through Exeter. Deloney tells an amusing story of how King Henry was riding forth west with one of his sons and some of his nobility, when "he met with a great number of waines loaden with cloth coming to London, and seeing them still drive one after another so many together, demanded whose they were. The wainemen answered in this sort: Coles of Reading, quoth they. Then, by and by, the King asked another, saying: Whose cloth is all this? Old Coles, quoth he. And againe anon after he asked the same questions to others, and still they answered, Old Coles. And it is to be remembered that the King met them in such a place so narrow and streight, that hee with the rest of his traine were faine to stand as close to the hedge, whilest the carts passed by, the which at that time being in number above two hundred, was neere hand an hour ere the King could get room to be gone; so that by his long stay, he began to be displeased, although the admiration of that sight did much qualify his furie; but breaking out in discontent, by reason of his stay, he said, I thought Old Cole had got a commission for all the carts in the country to carry his cloth. And how if he have (quoth one of the wainemen) doth that grieve you, good Sir? Yes, good Sir, said our King. What say you to that? The fellow, seeing the King (in asking the question) to bend his browes, though he knew not what he was, yet being abasht, he answered thus: Why, Sir, if you be angry, nobody can hinder you; for possibly, Sir, you have anger at commandment. The King, seeing him in uttering of his words to quiver and quake, laughed heartily at him … and by the time he came within a mile of Staines, he met another company of waines, in like sort laden with cloth, whereby the King was driven into a further admiration; and demanding whose they were, answere was made in this sort: They bee goodman Sutton's of Salisbury, good Sir. And by that time a score of them were past; he asked againe, saying, Whose are these? Sutton's of Salisbury, quoth they, and so still, so often as the King asked that question, they answered, Sutton's of Salisbury. God send me such more Suttons, said the King. And thus the further he travelled westward, more waines and more he met continually: upon which occasion he said to his nobles, that it would never grieve a King to die for the defence of a fertile country and faithful subjects. I alwayes thought (quoth he) that England's valor was more than her wealth, yet now I see her wealth sufficient to maintaine her valour, which I will seek to cherish in all I may, and with my sword keepe myselfe in possession of that I have."

Judging by what Deloney says, these clothiers were a merry set, and the journey to town was one long picnic. They were – or some were – of good family. Grey, the clothier of Gloucester, was of the noble race of Grey de Ruthyn, and FitzAllen, of Worcester, came of the Fitzallens, "that famous family whose patrimony lay about the town of Oswestrie, which towne his predecessors had inclosed with stately walls of stone."

The most famous wool merchant in the West was Tom Dove, of Exeter, concerning whom this song was sung: —

Welcome to town, Tom Dove, Tom Dove,

The merriest man alive.

Thy company still we love, we love,

God grant thee well to thrive.

And never will we depart from thee,

For better, for worse, my joy!

For thou shalt still have our good will,

God's blessing on my sweet boy!

In London Thomasine comported herself well, was cheerful and obliging. How the mercer's wife relished her introduction into the house we are not informed. But this good lady shortly after sickened and died, and the widower offered Thomasine his hand and his heart, which she accepted.

After three years Richard Bunsby, the mercer, died and left all he had to Thomasine, so that she, who had gone up to town as a serving girl, was now a rich widow, and withal young and pretty and attractive. She soon drew suitors about her, and her choice fell on "that worshipful merchant adventurer, Master John Gall, of S. Lawrence, Milk Street." He as well was wealthy and uxorious, and he allowed his wife to make donations for the relief of the poor of her native village, for which she ever retained a lingering attachment.

After the lapse of five years Thomasine was again a widow, and her second husband had followed the example of the first in leaving to her all his possessions.

She had not to wait long before fresh suitors buzzed about her like flies around a treacle barrel, and now, in the year 1497, she gave her hand to Sir John Percival, who in the following year became Lord Mayor of London. In memory of this event, she is traditionally held to have constructed a good road – as good roads went in those days – from Week S. Mary down to the coast, probably that over Week ford and through Poundstock, to either Wansum or Melhuc Mouth.

She long survived her third husband, and is supposed to have returned to end her days as the Lady Bountiful in her native village. By her will, made in 1510, she left goodly sums of money to Week S. Mary.

But both she and Sir John Percival had been already benefactors in London. Sir John had founded a chantry in S. Mary Woolnoth, and in 1539 is found an entry in the churchwardens' accounts of that parish recording that Dame Thomasine Percival had left money for the maintenance of the "beme light" in the church, i.e. the lamp before the rood. She had also left money to supply candles to burn about the sepulchre in the church on Easter Day, and he had bequeathed moneys for the repair of the ornaments of the church, for bell-ringing, for singers "for keeping the anthem," at his and her obits, and last but not least, "for a potation to the neighbours at the said obit."

Carew says: "And to show that virtue as well bare a part in the desert, as fortune in the means of her preferment, she employed the whole residue of her life and last widowhood to works no less bountiful than charitable, namely, repairing of highways, building of bridges, endowing of maidens, relieving of prisoners, feeding and apparelling the poor, etc. Among the rest, at this S. Mary Wike she founded a chantry and free-school, together with fair lodgings for the schoolmasters, scholars, and officers, and added £20 of yearly revenue for supporting the incident charges: wherein, as the bent of her desire was holy, so God blessed the same with all wished success; for divers of the best gentlemen's sons of Devon and Cornwall were there virtuously trained up, in both kinds of divine and human learning, under one Cholwel, an honest and religious teacher, which caused the neighbours so much the rather and the more to rue, that a petty smack only of Popery opened the gap to the oppression of the whole, by the statute made in Edward VI's reign, touching the suppression of chantries."

This disaster befell it in 1550, when all colleges, chantries, free chapels, fraternities, and guilds throughout the kingdom, with their lands and endowments, were alienated to the King – not because there was a "petty smack of Popery" in them, but because of the rapacity of the courtiers who desired to gather the lands and benefactions into their own soiled hands.

Mr. W. H. Tregellas says: "There are still to be seen in the remote and quiet little village of Week S. Mary, some five or six miles south of Bude, in the northern corner of Cornwall, the substantial remains of the good Thomasine's college and chantry, which she founded for the instruction of the youth of her native place.

"The buildings lie about a hundred yards east of the church (from the summit of whose grotesquely ornamented tower six-and-twenty parish churches may be discerned), and built into the modern wall of a cottage which stands inside the battlemented enclosure is a large carved granite stone (evidently one of two which once formed the tympanum of a doorway), on which the letter T stands out in bold relief. Probably it is the initial of the Christian name of our Thomasine; at any rate, it is pleasant to think it may be such."

The church and its stately tower were probably built by Thomasine, or, at all events, she would have largely contributed towards the building. That church is now, internally, a ghastly sight. At its "restoration" it was gutted, and is as bare as a railway station – a shell, and nothing more. But that it was not so in Dame Thomasine's time we may be well assured. A gorgeous screen extended across its nave and aisles, richly sculptured and coloured and gilt, the windows were filled with stained glass, and the bench ends were of carved oak. All this has been swept away.

In the Stratton churchwardens' accounts for 1513 we find that on the day upon which "My Lady Parcyvale's Meneday" came round – i.e. the day on which her death was called to mind – prayer was to be made for the repose of her soul, and two shillings and two pence paid to two priests, and for bread and ale.

THE MURDER OF NEVILL NORWAY

Mr. Nevill Norway was a timber and general merchant, residing at Wadebridge. He was the second son of William Norway, of Court Place, Egloshayle, who died in 1819, and Nevill was baptized at Egloshayle Church on November 5th, 1801.

In the course of his business he travelled about the country and especially attended markets, and he went to one at Bodmin on the 8th of February, 1840, on horseback.

About four o'clock in the afternoon he was transacting some little affair in the market-place, and had his purse in his hand, opened it and turned out some gold and silver, and from the sum picked out what he wanted and paid the man with whom he was doing business. Standing close by and watching him was a young man named William Lightfoot, who lived at Burlorn, in Egloshayle, and whom he knew well enough by sight.

Mr. Norway did not leave Bodmin till shortly before ten o'clock, and he had got about nine miles to ride before he would reach his house. The road was lonely and led past the Dunmeer Woods and that of Pencarrow.

He was riding a grey horse, and he had a companion, who proceeded with him along the road for three miles and then took his leave and branched off in another direction.

A farmer returning from market somewhat later to Wadebridge saw a grey horse in the road, saddled and bridled, but without a rider. He tried at first to overtake it, but the horse struck into a gallop and he gave up the chase; his curiosity was, however, excited, and upon meeting some men on the road, and making inquiry, they told him that they thought that the grey horse that had just gone by them belonged to Mr. Norway. This induced him to call at the house of that gentleman, and he found the grey steed standing at the stable gate. The servants were called out, and spots of blood were found upon the saddle. A surgeon was immediately summoned, and two of the domestics sallied forth on the Bodmin road, in quest of their master. The search was not successful that night, but later, one of the searchers perceiving something white in the little stream of water that runs beside the highway and enters the river Allen at Pendavey Bridge, they examined it, and found the body of their unfortunate master, lying on his back in the stream, with his feet towards the road, and what they had seen glimmering in the uncertain light was his shirt frill. He was quite dead.

The body was at once placed on the horse and conveyed home, where the surgeon, named Tickell, proceeded to examine it. He found that the deceased had received injuries about the face and head, produced by heavy and repeated blows from some blunt instrument, which had undoubtedly been the cause of death. A wound was discovered under the chin, into which it appeared as if some powder had been carried; and the bones of the nose, the forehead, the left side of the head and the back of the skull were frightfully fractured.

An immediate examination of the spot ensued when the body had been found, and on the left-hand side of the road was seen a pool of blood, from which to the rivulet opposite was a track produced by the drawing of a heavy body across the way, and footsteps were observed as of more than one person in the mud, and it was further noticed that the boots of those there impressed must have been heavy. There had apparently been a desperate scuffle before Mr. Norway had been killed.

There was further evidence. Two sets of footmarks could be traced of men pacing up and down behind a hedge in an orchard attached to an uninhabited house hard by; apparently men on the watch for their intended victim.

At a short distance from the pool of blood was found the hammer of a pistol that had been but recently broken off.

Upon the pockets of the deceased being examined, it became obvious that robbery had been the object of the attack made upon him, for his purse and a tablet and bunch of keys had been carried off.

Every exertion was made to discover the perpetrators of the crime, and large rewards were offered for evidence that should tend to point them out. Jackson, a constable from London, was sent for, and mainly by his exertions the murderers were tracked down. A man named Harris, a shoemaker, deposed that he had seen the two brothers, James and William Lightfoot, of Burlorn, in Egloshayle, loitering about the deserted cottage late at night after the Bodmin fair; and a man named Ayres, who lived next door to James Lightfoot, stated that he had heard his neighbour enter his cottage at a very late hour on the night in question, and say something to his wife and child, upon which they began to weep. What he had said he could not hear, though the partition between the cottages was thin.

This led to an examination of the house of James Lightfoot on February 14th, when a pistol was found, without a lock, concealed in a hole in a beam that ran across the ceiling. As the manner of Lightfoot was suspicious, he was taken into custody.

On the 17th his brother William was arrested in consequence of a remark to a man named Vercoe that he was in it as well as James. He was examined before a magistrate, and made the following confession: —

"I went to Bodmin last Saturday week, the 8th instant, and on returning I met my brother James just at the head of Dunmeer Hill. It was just come dim-like. My brother had been to Burlorn, Egloshayle, to buy potatoes. Something had been said about meeting; but I was not certain about that. My brother was not in Bodmin on that day. Mr. Vercoe overtook us between Mount Charles Turnpike Gate at the top of Dunmeer Hill and a place called Lane End. We came on the turnpike road all the way till we came to the house near the spot where the murder was committed. We did not go into the house, but hid ourselves in a field. My brother knocked Mr. Norway down; he snapped a pistol at him twice, and it did not go off. Then he knocked him down with the pistol. He was struck whilst on horseback. It was on the turnpike road between Pencarrow Mill and the directing-post towards Wadebridge. I cannot say at what time of the night it was. We left the body in the water on the left side of the road coming to Wadebridge. We took money in a purse, but I do not know how much it was. It was a brownish purse. There were some papers, which my brother took and pitched away in a field on the left-hand side of the road, into some browse or furze. The purse was hid by me in my garden, and afterwards I threw it over Pendavey Bridge. My brother drew the body across the road to the water. We did not know whom we stopped till when my brother snapped the pistol at him. Mr. Norway said, 'I know what you are about. I see you.' We went home across the fields. We were not disturbed by any one. The pistol belonged to my brother. I don't know whether it was broken; I never saw it afterwards; and I do not know what became of it. I don't know whether it was soiled with blood. I did not see any blood on my brother's clothes. We returned together, crossing the river at Pendavey Bridge and the Treraren fields to Burlorn village. My brother then went to his house and I to mine. I think it was handy about eleven o'clock. I saw my brother again on the Sunday morning. He came to my house. There was nobody there but my own family. He said, 'Dear me, Mr. Norway is killed.' I did not make any reply."

The prisoner upon this was remanded to Bodmin gaol, where his brother was already confined, and on the way he pointed out the furze bush in which the tablet and the keys of the deceased were to be found. James Lightfoot, in the meantime, had also made a confession, in which he threw the guilt of the murder upon his brother William.

This latter, when in prison, admitted that his confession had not been altogether true. He and his brother had met by appointment, with full purpose to rob the Rev. W. Molesworth, of S. Breock, returning from Bodmin market, and when James had snapped his pistol twice at Mr. Norway, he, William, had struck him with a stick on the back of his head and felled him from his horse, whereupon James had battered his head and face with the pistol.

The two wretched men were tried at Bodmin on March 30th, 1840, before Mr. Justice Coltman, and the jury returned a verdict of "Guilty"; they were accordingly both sentenced to death, and received the sentence with great stolidity.

Up to this time the brothers had been allowed no opportunity for communication, and the discrepancy in their stories distinctly enough showed that the object of each was to screen himself and to secure the conviction of the other.

After the passing of the sentence on them, they were conveyed to the same cell, and were now, for the first time, allowed to approach each other. They had scarcely met before, in the most hardened manner, they broke out into mutual recrimination, using the most horrible and abusive language of each other, and, not content with this, they flew at each other's throat, so that the gaolers were obliged to interfere and separate them and confine them in separate apartments.

On April 7th their families were admitted to bid them farewell, and the scene was most distressing. On Monday morning, April 13th, they were both executed, and it was said that upwards of ten thousand persons had assembled to witness their end.

As Mr. Norway's family was left in most straitened circumstances, a collection was made for them in Cornwall, and the sum of £3500 was raised on their behalf.

William Lightfoot was aged thirty-six and James thirty-three when hanged at Bodmin.

There is a monument to the memory of Mr. Norway in Egloshayle Church.

In the Cornwall Gazette, 17th April, 1840, the portraits of the murderers were given. Mention is made of the tragedy in C. Carlyon's Early Years, 1843. He gives the following story. At the time of the murder, Edmund Norway, the brother of Nevill, was in command of a merchant vessel, the Orient, on his voyage from Manilla to Cadiz. He wrote on the same day as the murder: —

"Ship Orient, from Manilla to Cadiz,"Feb. 8th, 1840.

"About 7.30 p.m. the island of S. Helena, N.N.W., distant about seven miles, shortened sail and rounded to, with the ship's head to the eastward; at eight, set the watch and went below – wrote a letter to my brother, Nevell Norway. About twenty minutes or a quarter before ten o'clock went to bed – fell asleep, and dreamt I saw two men attack my brother and murder him. One caught the horse by the bridle and snapped a pistol twice, but I heard no report; he then struck him a blow, and he fell off the horse. They struck him several blows, and dragged him by the shoulders across the road and left him. In my dream there was a house on the left-hand side of the road. At five o'clock I was called, and went on deck to take charge of the ship. I told the second officer, Mr. Henry Wren, that I had had a dreadful dream, and dreamt that my brother Nevell was murdered by two men on the road from S. Columb to Wadebridge; but I was sure it could not be there, as the house there would have been on the right-hand side of the road, but it must have been somewhere else. He replied, 'Don't think anything about it; you West-country people are superstitious; you will make yourself miserable the remainder of the passage. He then left the general orders and went below. It was one continued dream from the time I fell asleep until I was called, at five o'clock in the morning.

"Edmund Norway,"Chief Officer, Ship Orient."

There are some difficulties about this account. It is dated, as may be seen, February 8th, but it must have been written on February 9th, after Mr. Norway had had the dream, and the date must refer to the letter written to his brother and to the dream, and not to the time when the account was penned.

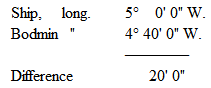

From the Cape of Good Hope to S. Helena the course would be about N.N.W., and with a fair wind the ship would cover about eighty or ninety miles in eight hours. So that at noon of the day February 8th she would be about one hundred miles S.S.E. of S. Helena, i.e. in about 5° W. longitude, as nearly as possible. The ship's clock would then be set, and they would keep that time for letter-writing purposes, meals, ship routine, etc.

The difference would be twenty minutes of longitude, and the difference in time between the two places one degree apart is four minutes. Reduce this to seconds: —

Therefore, if the murder was committed, say, at 10h. 30m. p.m. Bodmin time, the time on the ship's clock would be 10h. 28m. 40s. p.m. An inconsiderable difference.

The log-book of Edmund Norway is said to be still in existence.

One very remarkable point deserves notice. In his dream Mr. Edmund Norway saw the house on the right hand of the road, and as he remembered, on waking, that the cottage was on the left hand, he consoled himself with the thought that if the dream was incorrect in one point it might be in the whole. But he was unaware that during his absence from England the road from Bodmin to Wadebridge had been altered, and that it had been carried so that the position of the house was precisely as he saw it in his dream, and the reverse of what he had remembered it to be.

Another point to be mentioned is that one of the murderers wore on that occasion a coat which Mr. Norway had given him a few weeks before, out of charity.

Both brothers protested that they had not purposed the murder of Mr. Norway but of the Rev. Mr. Molesworth, parson of S. Breock, who they supposed was returning with tithe in his pocket. This, however, did not agree with the evidence that William Lightfoot had watched him counting his money at Bodmin, and then had made off.

On the occasion of the discovery of the murder, Sir William Molesworth sent his bloodhounds to track the murderers, but because they ran in a direction opposed to that which the constables supposed was the right one they were recalled. The hounds were right, the constables wrong.