Полная версия:

Various Harper's Young People, November 18, 1879

- + Увеличить шрифт

- - Уменьшить шрифт

Various

Harper's Young People, November 18, 1879 / An Illustrated Weekly

THE TOURNAMENT

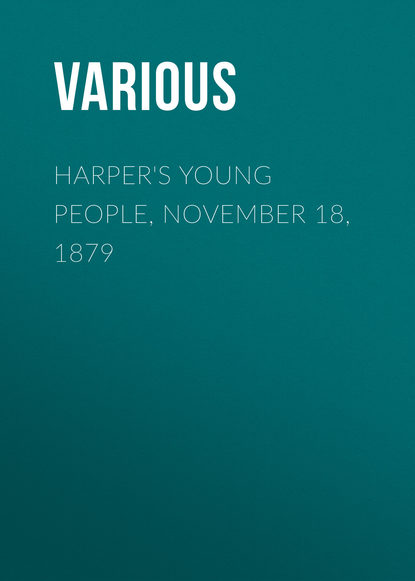

THE TOURNAMENT.—Drawn by James E. Kelly.

Great rivalry arose once between James and Henry, two school-mates and warm friends, and all on account of a pretty girl who went to the same school. Each one wanted to walk with her, and carry her books and lunch basket; and as Mary was a bit of a coquette, and showed no preference for either of her admirers, each tried to be the first to meet her in the shady winding lane that led from her house to the school. At last they determined to decide the matter in the old knightly manner, by a tournament. Two stout boys consented to act as chargers, and the day for the meeting was appointed.

It was Saturday afternoon, a half-holiday, when the rivals met in the back yard of Henry's house, armed with old brooms for lances, and with shields made out of barrel heads. The chargers backed up against the fence, the champions mounted and faced each other from opposite sides of the yard. The herald with an old tin horn gave the signal for the onset. There was a wild rush across the yard, and a terrific shock as the champions met. James's lance struck Henry right under the chin, and overthrew him in spite of his gallant efforts to keep his seat.

The herald at once proclaimed victory for James; and Henry, before he was allowed to rise from the ground, was compelled to renounce all intention of walking to school with Mary in the future.

THE BRAVE SWISS BOY

II.—A PERILOUS ADVENTURE.—(Continued.)

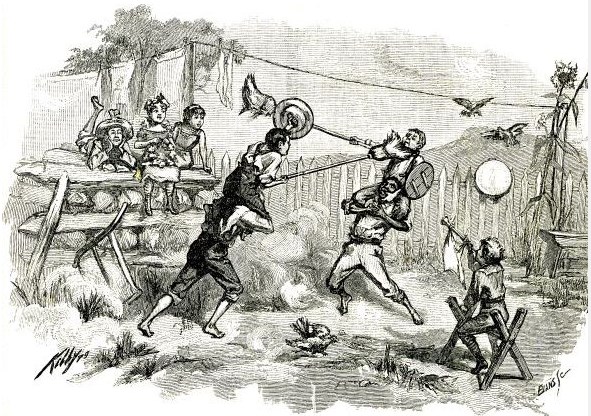

"WALTER AIMED TWO OR THREE BLOWS AT THE CREATURE'S BREAST."

In this dreadful crisis, Walter pressed as hard as he could against the rocky crag, having but one hand at liberty to defend himself against the furious attack of the bird. It was quite impossible for him to get at his axe, and the force with which he was assaulted caused him nearly to let go his hold. He tried to seize the vulture's throat and strangle it; but the bird was too active, and made all such attempts perfectly useless. He could scarcely hope to continue such a dangerous struggle much longer. He was becoming faint from terror, and his left hand was fast growing benumbed with grasping the rock. He had almost resigned himself to his fate, and expected the next moment to be dashed to pieces on the field of ice beneath. Suddenly, however, he recollected his pocket-knife, and a new ray of hope dawned. Giving up the attempt to clutch at the furious bird, he drew the knife out of his pocket, and opened it with his teeth, and aiming two or three blows at the creature's breast, he found at last that he had been successful in reaching some mortal part. The fluttering of the wings ceased, and the dying bird stained the virgin snow with its blood on the ice-field below. Walter was saved; there was no other enemy now to fear; his life was no longer in danger; but his energies were taxed to the utmost, and it was well for him that the terrible contest had lasted no longer.

Pale, trembling in every limb, and spattered with the vulture's blood as well as that which trickled from the many wounds he had received, the valiant young cragsman sank helplessly to the ground, where he lay for some minutes, paralyzed with the terrible exertion he had gone through. At length, however, he so far recovered himself as to be able to continue his fatiguing and dangerous journey, and soon succeeded in reaching the spot where he had left his jacket, shoes, and alpenstock. Having gained a place of safety, he poured forth his thanks to God for delivering him from such great danger, and began to bind up his wounds, which for the first time were now paining him. When this was accomplished in a rough and ready sort of way, he had a peep at the trophies in his bag, whose capture had been attended with such adventurous danger, and with the aid of his alpenstock succeeded in getting the dead body of the old bird, which he found had been struck right to the heart. But his knife he could not recover, so concluded that he must have dropped it after the deadly encounter.

"That doesn't matter much," said he to himself, as he looked at the size of the bird. "It is a good exchange; and if I give the stranger the old bird with the young ones, I dare say he will give me another knife. What a splendid creature! Fully four feet long, and the wings at least three yards across. How father will open his eyes when he sees the dead Lämmergeier—and the Scotch gentleman too!"

Tying the legs of the bird together with cord which he had fortunately brought, he slung it across his shoulder to balance the weight of the bag, and then started on his journey across the glacier, the foot of which he soon reached, and was then within hailing distance of the hotel where the stranger was residing.

It was a good thing that he had not been kept longer away, for the sun was beginning to set by the time he reached the valley, and only the highest peaks were lit up by its departing glory. Tired and hungry, Walter was thankful to find himself once more at the door of the inn, where there was the same crowd of travellers, guides, horses, and mules he had seen in the morning. His appearance had attracted general attention as he descended the last hill leading to the hotel.

"Why, I declare it's Watty Hirzel!" exclaimed one of the guides. "He was here this morning, and I declare he's got a young eagle hanging across his shoulder."

"Say an old vulture, Mohrle, and you'll be nearer the mark," replied the lad in a cheerful tone and with sparkling eyes; for he felt so proud of the triumph he had achieved that all fatigue seemed to be forgotten. "An old vulture, Mohrle, and a splendid fellow into the bargain! I've got the young ones in my bag here."

"You're a pretty fellow!" said another guide, with a sneer. "I suppose you mean to tell us that you've killed the old bird and carried off the young ones?"

"Yes, that is just what I mean to tell you," replied the boy, smiling, and paying no attention to the sneer of the other. "I've done it all alone. I took the youngsters out of the nest, and had a regular fight with the old ones afterward. I brought one of them home; but the other you will find somewhere in the Urbacht Valley, if you like to go and look for it."

"I think the lad speaks the truth," said Mohrle, gazing at Walter with astonishment and respect.—"You've had a long journey, my boy, and you're covered with blood. Did the old vulture hurt you?"

"Yes, the brute stuck his claws into me, and if I hadn't had a sharp knife in my pocket, it would have been all over with me. But let me through, for I want to take the young birds up stairs to a gentleman here."

Mohrle and the other guides who had surrounded the courageous boy would gladly have detained him longer to hear all the particulars of his daring adventure; but he pressed through the crowd, promising to tell them all about it afterward, and made his way up to the room occupied by Mr. Seymour, who received him with as much astonishment as the guides had done.

"There, Sir," exclaimed Walter, as he took the young vultures out of his bag and placed them on the floor—"there are the birds you wanted; and here is one of the old ones, which I brought with me from the Engelhorn. But you must let them have something to eat—the live ones, I mean; for they've had nothing for nearly a whole day, and are squealing for hunger."

Mr. Seymour stood for a moment speechless. He was filled with delight at the sight of the young birds he had so long wished for, but was at the same time dumfounded at the courage and honor of the young mountaineer.

"Is it possible?" he exclaimed at last. "Have you really ventured to risk your life, although I told you that I didn't want the birds?"

"Well, Sir, I know you said so; but I saw by your face that you would like to have them all the same; and so, as you had been so kind to me, I didn't mind running a little risk to please you, although it was hard work. So there they are; but you mustn't forget to feed them, or they will be starved to death before morning."

"Oh, we will take good care that they don't die of hunger," replied Mr. Seymour, ringing the bell. "I think, as you take such a warm interest in the welfare of the birds, you must feel rather hungry yourself. So sit down and have something to eat, and then you can tell me all about your adventure."

When the waiter came, some raw meat was ordered for the fledgelings—which were presently safely housed in the stable-yard—and a good dinner for Walter, who, aided by Mr. Seymour's encouraging remarks, did justice to a meal the like of which he had never before seen—a finale which was to him by far the most agreeable part of his day's work. Then the lad commenced, in simple language, to describe all that he had gone through, which, while it pleased his host thoroughly, caused him to feel still greater surprise and admiration at his young friend's unaffected bravery and presence of mind.

"You have performed a brave and daring action," said he, when Walter had finished his story. "I should call it a rash and fool-hardy adventure, had you not been actuated by a noble motive in carrying it out. A feeling of gratitude inspired you, and therefore God was with you, and preserved you. But tell me, boy, how is it that you had courage and resolution enough to expose yourself to such a frightful risk?"

"Well, Sir, I can't say," replied Walter, thoughtfully. "All I know is that I was determined to do it, and that is enough to help one over a great many hard things. At the very last, when I was attacked by the second vulture, and might have been easily thrown down the rocks, the thought came into my mind that you must and ought to have the birds; and then I recollected the knife in my pocket, which settled the business. Yes; that was it, Sir. You had been so generous to me, that I made up my mind to fight it out; and there's the end of it. I couldn't think of being ungrateful after so much kindness."

"Well, my lad, you have proved most clearly that you have a thankful heart and a cool and determined head," said Mr. Seymour, not without emotion. "Maintain these characteristics, and use them always for good and noble purposes, and I am sure you will find the end of every adventure as satisfactory as this has been to-day. I owe you a new knife and a suit of clothes; for the old vulture that has used you so badly was not in our bargain this morning. But we will talk about that another time. You had better go home now, for I think your father will begin to feel anxious about you, as it is getting late. I will come and see you in the morning."

Walter left the room in great glee. He stopped a few minutes in the court-yard to tell the impatient guides what he had gone through, and then hurried home as fast as he could, where he found his father waiting for him with some impatience. "Everything is settled, father!" he exclaimed, as he clasped him round the neck. "We shall get our cow back again now; for I've got the money, and Neighbor Frieshardt can't keep her any longer. I've brought it back with me from the Engelhorn."

The peasant could scarce believe the hurried words of the excited boy, and was afraid his head was turned, until Walter opened the little cupboard where he had put the money, and laid the two bright gold pieces on the table. There was no longer any room for doubt; and the poor man's eyes sparkled with delight as he looked at the sum which was just sufficient to pay his debt and rescue the cow from the hands of his neighbor.

"But how did you come by all this money, Watty?" he inquired. "I hope you have got it fairly and honestly?"

"Yes, quite honestly, father," replied the boy, with an open and exultant smile.

"Well, tell me— But no; I must go and get Liesli out of prison without a moment's delay. Come along with me to Neighbor Frieshardt's, Watty."

Away went the happy pair to the neighboring farm-house; and although Frieshardt looked sullen and displeased when Toni Hirzel laid the gold pieces on the table, it was no use for him to offer any resistance; so he went rather sulkily to the cow-house, and let out the captive animal, which was followed home by the peasant and his proud son, and got a capital supper in her old quarters. When this important business was accomplished, Walter repaired with his father to the little cottage again, and for the third and last time that day related all the adventures he had gone through in his hunt for the vulture's nest.

"Thanks be to God that He has watched over you, and brought you safely home again!" exclaimed the father, who had listened with a beating heart to his son's story. "It is a great blessing that we have got the money, for my cousin couldn't lend me any. But now promise me faithfully, youngster, that you will never go on such a dangerous errand again without speaking to me about it. It is a perfect miracle that you have come back alive! We have good reason to be thankful as long as we live that you didn't miss your footing or get killed by that savage vulture. But what I wonder most at is that you could muster up the pluck for such a risky business. It was too dangerous."

"Well, father, I did it for you, and so that we could get poor Liesli back again," replied the boy. "We could never have got on without the cow; and as the Scotch gentleman had been so kind to me, I made up my mind to get the young birds for him, and thought nothing about the danger I ran, if I could only accomplish my undertaking."

"I am very glad you have been so successful," said his father; "but never forget that your success is owing altogether to God's help, and don't forget to thank Him with all your heart for His watchful care."

"I'll be sure not to forget that, father," was the boy's reply. "I know that the very greatest courage is of no use without God's blessing; and I prayed for help before I set out, and several times afterward."

"That was right, Watty, my son. Never forget God, and He will always be with you, and protect you all your life long. And now, good-night, dear boy."

"Good-night, father," replied Walter, heartily; and both retired to their humble beds, and were soon wrapped in deep and healthful slumber.

[to be continued.]A GIGANTIC JELLY-FISH

Few excursions can be proposed more acceptable to young folks than going a-fishing, and perhaps the most delightful sort of fishing is to be had by accompanying some old fisherman out into the broad ocean.

There are many circumstances that contribute to make a day's sport of this kind more enjoyable than pond or river fishing, and not the least of these consists in the wonderful variety of the creatures to be caught.

In our inland streams and lakes in any given locality the kinds of fish to be caught are well known, and, comparatively speaking, there are not many different sorts; but in ocean fishing the oldest fisherman, and those most accustomed to the sorts of fish generally found in their fishing grounds, every once in a while happen upon creatures the likes of which have seldom, perhaps never, been seen before. Only a short time since a Nantucket fisherman, rowing slowly along, buried the prow of his boat in some partly yielding substance that brought him to a stand-still. Somewhat startled, he went forward, oar in hand, to find his little craft imbedded in the body of an enormous jelly-fish, the largest ever seen. The soft and yielding body of the creature offered so little resistance to his oar when he tried to push off, and he saw himself so hopelessly entangled in the mass of slime and tentacles, that, instead of attempting to free himself, he determined to tow it ashore, which he did by passing a sail-cloth under its body and rowing slowly homeward.

THE CAPTURE.

Of course the rough encounter with the boat had considerably mutilated the jelly-fish, and torn away portions of the long thread-like processes or tentacles that hang from the central mass; yet these, when the creature was laid along the sand of the ocean beach, measured over two hundred feet in length, and it is conjectured that, uninjured and stretched to their utmost length, they could not have been less than three hundred feet long. The great shield-like body of the animal was found to be over nine feet in diameter, two feet more than the largest heretofore known, which is described by Professor Agassiz, who measured it while it was floating lazily on the surface of the water. This specimen was so large that the professor feared his account of it might be considered exaggerated.

HYDROID FROM WHICH THE JELLY-FISH GROWS.

The monster when alive looks as much as anything like an immense circular plate or dish of glass floating bottom upward on the sea. The color of the body is a brownish-red, with a rather broad margin of creamy white edged with blue, while the tentacles—pink, blue, brown, and purple—hang like skeins of colored glass threads from the under parts of the shield. Very beautiful are these threads, glistening with a silky lustre beneath the waves, but they are extremely dangerous, too. Each of these threads, in fact, contains myriads of cells, in each one of which is coiled up, ready to be darted forth on contact with any living substance, a whip-like lance finer than the finest cambric needle. Millions of these stings entering at once cause a sensation like that of a violent electric shock, paralyzing and often killing the creature with which they come in contact.

This gigantic creature grows from the small one, called a hydroid, represented in the small cut. You see the hydroid does not in the least resemble a jelly-fish. Perhaps the strangest thing about these wonderful lumps of animated jelly is that their young are not jelly-fishes at all, but an entirely different sort of animals. Sometimes they take the shape of a pile of platters, which finally separate and become individual jelly-fish; sometimes they grow into living plants which bear eggs like fruit, which eggs hatch and finally become jelly-fish. No fairy tale can afford instances of transformations so surprising as do these animals—more like animated bubbles than anything else to which they can be compared; transparent and exhibiting the most brilliant colors, they dissolve away when stranded so completely that no trace of their substance seems to remain.

THE FIRST DROP OF BITTERNESS.

THE FIRST DROP OF BITTERNESS

Come, little one, open your mouth!I know it is bitter to drink;But if you'll stop squirming and squalling,You'll have it all down in a wink.The poor little baby is sick,And this is to cure the bad pain;So swallow the medicine, darling,And soon you can frolic again.How glad should we be, who are older,And have bitter burdens to bear,To find out some wonderful doctorWith cures for each sorrow and care!At the Bottom of a Mine.—Years ago some Welsh miners, in exploring an old pit that had been long closed, found the body of a young man dressed in a fashion long out of date. The peculiar action of the air of the mine had been such as to preserve the body so perfectly that it appeared asleep rather than dead. The miners were puzzled at the circumstance; no one in the district had been missed within their remembrance; and at last it was resolved to bring the oldest inhabitant—an old lady, long past her eightieth year, who had lived single in the village the whole of her life. On being brought into the presence of the body, a strange scene occurred: the old lady fell on the corpse, kissed and addressed it by every term of loving endearment, couched in the quaint language of a by-gone generation. "He was her only love; she had waited for him during her long life; she knew that he had not forsaken her."

The old woman and the young man had been betrothed sixty years before. The lover had disappeared mysteriously, and she had kept faithful during that long interval. Time had stood still with the dead man, but had left its mark on the living woman. The miners who were present were a rough set, but very gently, and with tearful eyes, they removed the old lady to her house, and the same night her faithful spirit rejoined that of her long-lost lover.

THAT EARTHQUAKE!

Did you ever play in a cellar? I don't mean a cellar with a smooth floor, and coal-bins, and a big furnace, and shelves with jars of nice jam on them and glasses of jelly; I've been in that kind of a cellar too—I like quince jelly the best; it's first rate spread on bread and butter—but I'm talking of another kind of a cellar, one with the house all taken away, and only a big brick chimney left in the centre, with the top knocked off of that, and bricks and pieces of stone and chunks of mortar scattered all round; with berry bushes growing in one corner, and wild vines growing all around the edges.

There was just such a cellar as this where I used to live, and Kate and Teddy Ames, who lived in the next house, used to come over and play in the cellar with Billy and me.

Billy was my brother, eight years old, and the best fellow to play with you ever saw, because he was always "sperimentin"—that's what mother called it, and it meant trying to do things.

Billy knew a great deal more than all the rest of the boys in our school, and he was very fond of reading, but it didn't make him stupid a bit, for whatever he read about he always wanted to go right off and see if he could do it too. This made great fun for us, and got Billy into lots of scrapes.

When he tried to do anything like what he had read about, he never would be satisfied until he could do it all exactly as the reading said it was. So when we had read Robinson Crusoe together—I think Billy knew it all by heart as well as he knew the table of sevens in the multiplication table—he said, "Now let's play Robinson Crusoe." First he called the old open cellar Crusoe's cave, and scooped out a place between some stones and made it clean, and I braided a little mat and a curtain out of some long grass for it, and there he put his old copy of Robinson Crusoe, and for days and days, after school was out, and in vacation, we played Robinson Crusoe together.

Kate was a parrot, and wanted a great deal of cracker, Teddy was a goat, and I was the dog and "man Friday" by turns. We walked about in the cellar pretending to look for the print of naked feet, Billy going in front carrying a rusty old broken musket we had found in the garret, and a piece of rubber hose (Billy always could find or make anything we wanted) for a telescope, which he used to look through to see if there were any savages in sight when he climbed up to the edge of the cellar.

The cellar was really an island, just like Robinson Crusoe's; for Billy and Teddy had digged a ditch all round it, and filled it with water; but it was a very trying sort of an ocean, 'cause we had to fill it up every morning.

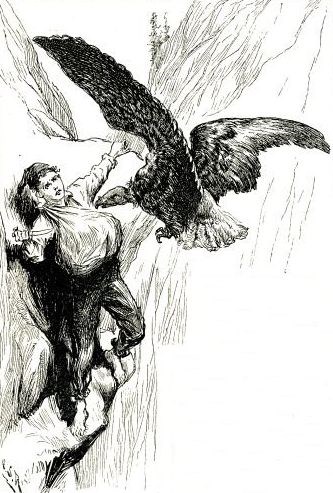

BILLY WATCHING FOR SAVAGES.—Drawn by C. S. Reinhart.

Teddy, who could whittle nicely, made some little canoes, and when Billy was looking through the hose for savages, it was Teddy's part to poke the canoes with a long stick like a fish-pole, so they would float right in front of Billy's hose. Then Billy would scramble down the wall, and come running to us 'round behind the chimney, and tell us to lie very still, for there were seven canoes full of cruel savages sailing for the island.

Then we would all creep close to the chimney on the shady side, and not go out for two weeks, which meant about fifteen minutes (Billy counted seven minutes to a week), and we liked this part of Robinson Crusoe very much indeed, 'cause then Billy would give us what he called "rations"—nice sugary raisins, dried beef, and seed cookies, which he said were cocoa-nuts given to him by monkeys that lived in tall trees in another part of the island, where we should go with him some time when he was sure the savages had left.