Полная версия:

Various Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 66, No. 410, December 1849

- + Увеличить шрифт

- - Уменьшить шрифт

Various

Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 66, No. 410, December 1849

THE NATIONAL DEBT AND THE STOCK EXCHANGE.1

The idea of associating history with some specific locality or institution, has long ago occurred to the skilful fabricators of romance. If old walls could speak, what strange secrets might they not reveal! The thought suggests itself spontaneously even to the mind of the boy; and though it is incapable of realisation, writers – good, bad, and indifferent – have seriously applied themselves to the task of extracting sermons from the stones, and have feigned to reproduce an audible voice from the vaults of the dreary ruin. Such was at least the primary idea of Scott, incomparably the greatest master of modern fiction, whilst preparing his materials for the construction of the Heart of Mid-Lothian. Victor Hugo has made the Cathedral of Paris the title and centre-point of his most stirring and animated tale. Harrison Ainsworth, who seems to think that the world can never have too much of a good thing, has assumed the office of historiographer of antiquity, and has treated us in succession to Chronicles of Windsor Castle, the Tower, and Old St Paul's. Those of the Bastile have lately been written by an author of no common power, whose modesty, rarely imitated in these days, has left us ignorant of his name; and we believe that it would be possible to augment the list to a considerable extent. In all those works, however, history was the subsidiary, while romance was the principal ingredient; we have now to deal with a book which professes to abstain from romance, though, in reality, no romance whatever has yet been constructed from materials of deeper interest. We allude, of course, to the work of Mr Francis; Mr Doubleday's treatise is of a graver and a sterner nature.

We dare say, that no inconsiderable portion of those who derive their literary nutriment from Maga, may be at a loss to understand what element of romance can lie in the history of the Stock Exchange. With all our boasted education, we are, in so far as money-matters are concerned, a singularly ignorant people. That which ought to be the study of every citizen, which must be the study of every politician, and without a competent knowledge of which the exercise of the electoral franchise is a blind vote given in the dark, is as unintelligible as the Talmud to many persons of more than ordinary accomplishment and refinement. The learned expounder of Thucydides would be sorely puzzled, if called upon to give an explanation of the present funding system of Great Britain. The man in easy circumstances, who draws his dividend at the Bank, knows little more about the funds than that they mysteriously yield him a certain return for capital previously invested, and that the interest he receives comes, in some shape or other, from the general pocket of the nation. He is aware that consols oscillate, but he does not very well understand why, though he attributes their rise or fall to foreign news. It never occurs to him to inquire for what reason that which yields a certain return, is yet liable to such surprising and violent fluctuations; he shakes his head in despair at the mention of foreign exchanges, and is not ashamed to avow his incapacity to grapple with the recondite question of the currency. And yet it may not only be safely, but it ought to be most broadly averred, that without a due comprehension of the monetary system of this country, and the general commercial principles which regulate the affairs of the world, history is nothing more than a tissue of barren facts and perpetual contradictions, which it is profitless to contemplate, and utterly impossible to reconcile. Nay more, all history which is written by authors, who have failed to acknowledge the tremendous potency of the monetary power in directing the destinies of nations, and who have neglected to scrutinise closely the source and operation of that power, must necessarily be fallacious, and can only mislead the reader, by false pictures of the condition of the present as contrasted with that of a former age. No eloquence, no genius, will avail to compensate for that radical defect, with which some most popular writers are justly chargeable, and a glaring instance of which we propose to examine in the course of the present paper.

The study is said to be a dry one. Certainly, until we have mastered the details, it does look forbidding enough; but, these once mastered, our eyes appear to be touched with fairy ointment. What formerly was confusion, worse than Babel, assumes a definite order. We behold, in tangible form, a power so terribly strong that with a touch it can paralyse armies. We behold it gradually weaving around us a net, from which it is impossible to escape, and claiming with a stern accent, which brooks no denial, a right of property in ourselves, our soil, our earnings, our industry, and our children. To its influence we can trace most of the political changes which perplex mankind, and which seem to baffle explanation. Like the small reptile of the old Northumbrian legend, it has grown into a monstrous dragon, capable of swallowing up both herd and herdsman together. The wisest of our statesmen have tried to check its advance and failed; the worst of them have encouraged its growth, and almost declared it harmless; the most adroit have yielded to its power. Interest after interest has gone down in the vain struggle to oppose it, and yet its appetite still remains as keen and insatiable as ever.

When, in future years, the history of this great nation and its dependencies shall be adequately written, the annalist must, perforce, give due prominence to that power which we weakly and foolishly overlook. He will then see, that the matchless industry displayed by Great Britain is far less the spontaneous result of bold and honest exertion, than the struggle of a dire necessity which compels us to go on, because it is death and ruin to stand still. He will understand the true source of all our marvellous machinery, of that skill in arts which the world never witnessed before, of our powers of production pushed to the utmost possible extent. And he will understand more. He will be able to comprehend why, within the circuit of one island, the most colossal fortunes and the most abject misery should have existed together; why Britain, admitted to be the richest of the European states, and in one sense imagined to be the strongest, should at this moment exercise less influence in the councils of the world than she did in the days of Cromwell, and, though well weaponed, be terrified to strike a blow, lest the recoil should prove fatal to herself. The knowledge of such things is not too difficult for our attainment; and attain it we must, if, like sensible men, we are desirous to ascertain the security or the precariousness of our own position.

The history of the Stock Exchange involves, as a matter of necessity, the history of our national debt. From that debt the whole fabric arose; and, interesting as are many of the details connected with stock-jobbing, state-loans, lotteries, and speculative manias, the origin of the mystery appears to us of far higher import. It involves political considerations which ought to be pondered at the present time, because it has lately been averred, by a writer of the very highest talent, that the Revolution of 1688 was the cause of unmingled good to this country. That position we totally deny. Whatever may be thought of the folly of James II., in attempting to force his own religion down the throats of his subjects – however we may brand him as a bigot, or denounce him for an undue exercise of the royal prerogative – he cannot be taxed with financial oppression, or general state extravagance. On the contrary, it is a fact that the revenue levied by the last of the reigning Stuarts was exceedingly moderate in amount, and exceedingly well applied for the public service. It was far less than that levied by the Long Parliament, which has been estimated at the sum of £4,862,700 a-year. The revenue of James, in 1688, amounted only to £2,001,855; and at this charge he kept together a strong and well-appointed fleet, and an army of very nearly twenty thousand men. The nation was neither ground by taxes, nor impoverished by wars; and whatever discontent might have been excited by religious bickerings, and even persecution, it is clear that the great body of the people could not be otherwise than happy, since they were left in undisturbed possession of their own earnings, and at full liberty to enjoy the fruits of their own industry and skill. As very brilliant pictures have been drawn of the improved state of England now, contrasted with its former position under the administration of James, we think it right to exhibit another, which may, possibly, surprise our readers. It is taken, from Mr Doubleday's Financial History of England, a work of absorbing interest and uncommon research: we have tested it minutely, by reference to documents of the time, and we believe it to be strictly true, as it is unquestionably clear in its statements.

"The state of the country," says Mr Doubleday, "was, at the close of the reign of James II., very prosperous. The whole annual revenue required from his subjects, by this king, amounted to only a couple of millions of pounds sterling, – these pounds being, in value, equal to about thirty shillings of the money of the present moment. So well off and easy, in their circumstances, were the mass of the people, that the poor-rates, which were in those days liberally distributed, only amounted to £300,000 yearly. The population, being rich and well fed, was moderate in numbers. No such thing as 'surplus population' was even dreamed of. Every man had constant employment, at good wages; bankruptcy was a thing scarcely known; and nothing short of sheer and great misfortune, or culpable and undeniable imprudence, could drive men into the Gazette bankrupt-list, or upon the parish-books. In trade, profits were great and competition small. Six per cent was commonly given for money when it was really wanted. Prudent men, after being twenty years in business, generally retired with a comfortable competence: and thus competition was lessened, because men went out of business almost as fast as others went into it; and the eldest apprentice was frequently the active successor of his retired master, sometimes as the partner of the son, and sometimes as the husband of the daughter. In the intercourse of ordinary life, a hospitality was kept up, at which modern times choose to mock, because they are too poverty-stricken to imitate it. Servants had presents made to them by guests, under the title of 'vails,' which often enabled them to realise a comfortable sum for old age. The dress of the times was as rich, and as indicative of real wealth, as the modes of living. Gold and silver lace was commonly worn, and liveries were equally costly. With less pretence of taste and show, the dwellings were more substantially built; and the furniture was solid and serviceable, as well as ornamental – in short all that it seemed to be."

The above remarks apply principally to the condition of the middle classes. If they be true, as we see no reason to doubt, it will at once be evident that things have altered for the worse, notwithstanding the enormous spread of our manufactures, the creation of our machinery, and the constant and continuous labour of more than a century and a half. But there are other considerations which we must not keep out of view, if we wish to arrive at a thorough understanding of this matter. Mr Macaulay has devoted the most interesting chapter of his history to an investigation of the social state of England under the Stuarts. Many of his assertions have, as we observe, been challenged; but there is one which, so far as we are aware, has not yet been touched. That is, his picture of the condition of the labouring man. We do not think it necessary to combat his theory, as to the delusion which he maintains to be so common, when we contemplate the times which have gone by, and compare them with our own. There are many kinds of delusion, and we suspect that Mr Macaulay himself is by no means free from the practice of using coloured glasses to assist his natural vision. But there are certain facts which cannot, or ought not, to be perverted, and from those facts we may draw inferences which are almost next to certainty. Mr Macaulay, in estimating the condition of the labouring man in the reign of King James, very properly selects the rate of wages as a sound criterion. Founding upon data which are neither numerous nor distinct, he arrives at the conclusion, that the wages of the agricultural labourer of that time, or rather of the time of Charles II., were about half the amount of the present ordinary rates. At least so we understand him, though he admits that, in some parts of the kingdom, wages were as high as six, or even seven shillings. The value, however, of these shillings – that is, the amount of commodities which they could purchase – must, as Mr Macaulay well knows, be taken into consideration; and here we apprehend that he is utterly wrong in his facts. The following is his summary: —

"It seems clear, therefore, that the wages of labour, estimated in money, were, in 1685, not more than half of what they now are; and there were few articles important to the working man of which the price was not, in 1685, more than half of what it now is. Beer was undoubtedly much cheaper in that age than at present. Meat was also cheaper, but was still so dear that hundreds of thousands of families scarcely knew the taste of it. In the cost of wheat there has been very little change. The average price of the quarter, during the last twelve years of Charles II., was fifty shillings. Bread, therefore, such as is now given to the inmates of a workhouse, was then seldom seen, even on the trencher of a yeoman or of a shopkeeper. The great majority of the nation lived almost entirely on rye, barley, and oats."

If this be true, there must be a vast mistake somewhere – a delusion which most assuredly ought to be dispelled, if any amount of examination can serve that purpose. No fact, we believe, has been so well ascertained, or so frequently commented on, as the almost total disappearance of the once national estate of yeomen from the face of the land. How this could have happened, if Mr Macaulay is right, we cannot understand; neither can we account for the phenomenon presented to us, by the exceedingly small amount of the poor-rates levied during the reign of King James. One thing we know, for certain, that, in his calculation of the price of wheat, Mr Macaulay is decidedly wrong – wrong in this way, that the average which he quotes is the highest that he could possibly select during two reigns. Our authority is Adam Smith, and it will be seen that his statement differs most materially from that of the accomplished historian.

"In 1688, Mr Gregory King, a man famous for his knowledge of matters of this kind, estimated the average price of wheat, in years of moderate plenty, to be to the grower 3s. 6d. the bushel, or eight-and-twenty shillings the quarter. The grower's price I understand to be the same with what is sometimes called the contract price, or the price at which a farmer contracts for a certain number of years to deliver a certain quantity of corn to a dealer. As a contract of this kind saves the farmer the expense and trouble of marketing, the contract price is generally lower than what is supposed to be the average market price. Mr King had judged eight-and-twenty shillings the quarter to be, at that time, the ordinary contract price in years of moderate plenty." – Smith's Wealth of Nations.

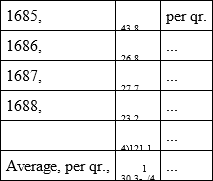

In corroboration of this view, if so eminent an authority as Adam Smith requires any corroboration, we subjoin the market prices of wheat at Oxford for the four years of James's reign. The averages are struck from the highest and lowest prices calculated at Lady-day and Michaelmas.

But the Oxford returns are always higher than those of Mark Lane, which latter again are above the average of the whole country. So that, in forming an estimate from such data, of the general price over England, we may be fairly entitled to deduct two shillings a quarter, which will give a result closely approximating to that of Gregory King. We may add, that this calculation was approved of and repeated by Dr Davenant, who is admitted even by Mr Macaulay to be a competent authority.

Keeping the above facts in view, let us attend to Mr Doubleday's statement of the condition of the working men, in those despotic days, when national debts were unknown. It is diametrically opposed in every respect to that of Mr Macaulay: and, from the character and research of the writer, is well entitled to examination: —

"The condition of the working classes was proportionably happy. Their wages were good, and their means far above want, where common prudence was joined to ordinary strength. In the towns the dwellings were cramped, by most of the towns being walled; but in the country, the labourers were mostly the owners of their own cottages and gardens, which studded the edges of the common lands that were appended to every township. The working classes, as well as the richer people, kept all the church festivals, saints' days, and holidays. Good Friday, Easter and its week, Whitsuntide, Shrove Tuesday, Ascension-day, Christmas, &c., were all religiously observed. On every festival, good fare abounded from the palace to the cottage; and the poorest wore strong broad-cloth and homespun linen, compared with which the flimsy fabrics of these times are mere worthless gossamers and cobwebs, whether strength or value be looked at. At this time, all the rural population brewed their own beer, which, except on fast-days, was the ordinary beverage of the working man. Flesh meat was commonly eaten by all classes. The potato was little cultivated; oatmeal was hardly used; even bread was neglected where wheat was not ordinarily grown, though wheaten bread (contrary to what is sometimes asserted) was generally consumed. In 1760, a later date, when George III. began to reign, it was computed that the whole people of England (alone) amounted to six millions. Of these, three millions seven hundred and fifty thousand were believed to eat wheaten bread; seven hundred and thirty-nine thousand were computed to use barley bread; eight hundred and eighty-eight thousand, rye bread; and six hundred and twenty-three thousand, oatmeal and oat-cakes. All, however, ate bacon or mutton, and drank beer and cider; tea and coffee being then principally consumed by the middle classes. The very diseases attending this full mode of living were an evidence of the state of national comfort prevailing. Surfeit, apoplexy, scrofula, gout, piles, and hepatitis; agues of all sorts, from the want of drainage; and malignant fevers in the walled towns, from want of ventilation, were the ordinary complaints. But consumption in all its forms, marasmus and atrophy, owing to the better living and clothing, were comparatively unfrequent: and the types of fever, which are caused by want, equally so."

We shall fairly confess that we have been much confounded by the dissimilarity of the two pictures; for they probably furnish the strongest instance on record of two historians flatly contradicting each other. The worst of the matter is, that we have in reality few authentic data which can enable us to decide between them. So long as Gregory King speaks to broad facts and prices, he is, we think, accurate enough; but whenever he gives way, as he does exceedingly often, to his speculative and calculating vein, we dare not trust him. For example, he has entered into an elaborate computation of the probable increase of the people of England in succeeding years, and, after a show of figures which might excite envy in the breast of the Editor of The Economist, he demonstrates that the population in the year 1900 cannot exceed 7,350,000 souls. With half a century to run, England has already more than doubled the prescribed number. Now, though King certainly does attempt to frame an estimate of the number of those who, in his time, did not indulge in butcher meat more than once a week, we cannot trust an assertion which was, in point of fact, neither more nor less than a wide guess; but we may, with perfect safety, accept his prices of provisions, which show that high living was clearly within the reach of the very poorest. Beef sold then at 11/3d., and mutton at 2-1/4d. per lb.; so that the taste of those viands must have been tolerably well known to the hundreds of thousands of families whom Mr Macaulay has condemned to the coarsest farinaceous diet.

It is unfortunate that we have no clear evidence as to the poor-rates, which can aid us in elucidating this matter. Mr Macaulay, speaking of that impost, says, "It was computed, in the reign of Charles II., at near seven hundred thousand pounds a-year, much more than the produce either of the excise or the customs, and little less than half the entire revenue of the crown. The poor-rate went on increasing rapidly, and appears to have risen in a short time to between eight and nine hundred thousand a-year – that is to say, to one-sixth of what it now is. The population was then less than one-third of what it now is." This view may be correct, but it is certainly not borne out by Mr Porter, who says that, "so recently as the reign of George II., the amount raised within the year for poor-rates and county-rates in England and Wales, was only £730,000. This was the average amount collected in the years 1748, 1749, 1750." To establish anything like a rapid increase, we must assume a much lower figure than that from which Mr Macaulay starts. A rise of £30,000 in some sixty years is no remarkable addition. Mr Doubleday, as we have seen, estimates the amount of the rate at only £300,000.

But even granting that the poor-rate was considered high in the days of James, it bore no proportion to the existing population such as that of the present impost. The population of England has trebled since then, and we have seen the poor-rates rise to the enormous sum of seven millions. Surely that is no token of the superior comfort of our people. We shall not do more than allude to another topic, which, however, might well bear amplification. It is beyond all doubt, that, before the Revolution, the agricultural labourer was the free master of his house and garden, and had, moreover, rights of pasturage and commonty, all which have long ago disappeared. The lesser freeholds, also, have been in a great measure absorbed. When a great national poet put the following lines into the mouth of one of his characters, —

"Even therefore grieve I for those yeomen,England's peculiar and appropriate sons,Known in no other land. Each boasts his hearthAnd field as free, as the best lord his barony,Owing subjection to no human vassalage,Save to their king and law. Hence are they resolute,Leading the van on every day of battle,As men who know the blessings they defend;Hence are they frank and generous in peace,As men who have their portion in its plenty.No other kingdom shows such worth and happinessVeiled in such low estate – therefore I mourn them,"we doubt not that he intended to refer to the virtual extirpation of a race, which has long ago been compelled to part with its birthright, in order to satisfy the demands of inexorable Mammon. Even whilst we are writing, a strong and unexpected corroboration of the correctness of our views has appeared in the public prints. Towards the commencement of the present month, November, a deputation from the agricultural labourers of Wiltshire waited upon the Hon. Sidney Herbert, to represent the misery of their present condition. Their wages, they said, were from six to seven shillings a-week, and they asked, with much reason, how, upon such a pittance, they could be expected to maintain their families. This is precisely the same amount of nominal wage which Mr Macaulay assigns to the labourer of the time of King James. But, in order to equalise the values, we must add a third more to the latter, which is at once decisive of the question. Perhaps Mr Macaulay, in a future edition, will condescend to explain how it is possible that the labourer of our times can be in a better condition than his ancestor, seeing that the price of wheat is nearly doubled, and that of butcher-meat fully quadrupled? We are content to take his own authorities, King and Davenant, as to prices; and the results are now before the reader.