Полная версия:

Various Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 61, No. 377, March 1847

- + Увеличить шрифт

- - Уменьшить шрифт

Various

Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 61, No. 377, March 1847

ON PAUPERISM, AND ITS TREATMENT

“If I oftMust turn elsewhere – to travel near the tribesAnd fellowships of men, and see ill sightsOf maddening passions mutually inflamed;Must hear humanity in fields and grovesPipe solitary anguish; or must hangBrooding above the fierce confederate stormOf sorrow, barricadoed evermoreWithin the walls of cities – may these soundsHave their authentic comment!”Wordsworth.In order to deal effectively with pauperism, it is necessary to know the causes which lead to the impoverishment of individuals and masses of individuals, and to be familiar with the condition, manners, customs, habits, prejudices, feelings, and superstitions of the poor.

We do not propose to institute an elaborate inquiry into the causes of pauperism, or to make the topic a subject of separate investigation. Our chief object will be, to collect into classes those of the poor who are known, from personal observation, to become chargeable to parishes, which process will afford abundant scope for remark upon the causes which led to their impoverishment. We may require the company of the reader with us in the metropolis for a short space, and may satisfy him that he need not travel ten miles from his own door in search of valuable facts, and at the same time convince him that pauperism is not that simple compact evil which many would wish him to believe. We might also show that, in the metropolis and its suburbs, there exist types of every class of poor that can be found in the rural and manufacturing districts of England; just as it might be shown, that its inhabitants consist of natives of every county in the three kingdoms. Its fixed population, according to the quarter in which they live, would be found to resemble the inhabitants of a great town, a cathedral city, or a seat of manufactures. And that portion of its inhabitants which may be regarded as migratory, would complete the resemblance, except that the shadows would be deeper and the outline more jagged. These persons make London their winter-quarters. At other seasons they are employed by the farmer and the grazier. It is a fact, that the most onerous part of the duties of the metropolitan authorities are those which relate to these migratory classes. Among them are the most lawless and the most pauperised of the agricultural districts. Others, during the spring, summer, and autumn months, were engaged, or pretend that they were engaged (and the statement cannot be tested,) in the cutting of vegetables, the making of hay, the picking of pease, beans, fruit, and hops, and in harvest work. Or they travelled over the country, frequenting fairs, selling, or pretending to sell, knives, combs, and stay-laces. Or they were knife-grinders, tinkers, musicians, or mountebanks. As the winter approaches, they flock into the town in droves. There they obtain a precarious subsistence in ways unknown; some pick up the crumbs that fall from the rich man’s table, others overcrowd the workhouses. It would lead to many curious and useful results if this matter were fully investigated. The reader’s company is not, however, required for this purpose; at the same time, the previous remarks may, in some measure, prepare his mind for the consideration of kindred topics. It may introduce a train of reflection, and prompt him to inquire whether the wandering habits of these outcasts have been in any degree engendered by the strict workhouse system and workhouse test enforced in their native villages, by the destruction of cottages, and the breaking up of local associations, and whether these habits have been fostered by the facilities with which a bed and a mess of porridge may be obtained at the unions, without inquiry into their business and object in travelling.

Let us steer our course along the silent “highway,” the Thames, and make inquiries of the few sailor-looking men who may still be seen loitering at the several “stairs;” we shall learn that not many years since these narrow outlets were the marts of a thriving employment, and that there crowds of independent and privileged watermen plied successfully for fares. These places are now forsaken, and the men have lost their occupation. Some still ply; and the cry at a few stairs, of “Boat, your honour?” may still be heard. Others have been draughted into situations connected with the boat companies, which support them during the summer months. A large number swell the crowds of day-labourers, who frequent the legal quays, the sufferance wharves, and the docks. And the rest, unfitted by their age or habits to compete with labourers accustomed to the other fields of occupation, sink lower and lower; sustained for a time by the helping hands of comrades and old patrons, but at last obliged to seek a refuge at the parish workhouse. Death also does his part. At Paul’s Wharf stairs, a few inches above high-water mark, a few shrubs have been planted against the river wall – and above them is a small board, rudely cut, and on it are inscribed these words, – “To the memory of old Browny, who departed this life, August, 26, 1846.” Let us stroll to the coach offices. Here again we see a great change – great to the common eye of the public, who miss a raree show, and a still greater one to the hundreds and thousands of human beings whose subsistence depended upon the work done at those places. A few years ago, the reader may have formed one of a large group of spectators, collected at the “Peacock” at Islington, to witness the departure of the night mails, on the high north road. The cracking of whips, the blowing of horns, the prancing horses, the bustle of passengers and porters, and the consciousness of the long dreary distance they had to go, exercised an enduring influence upon the imagination and memory of the youthful observer. Now, a solitary slow coach may be sometimes seen. In those days, all the outlets of the metropolis presented similar scenes. Then call to remembrance the business transacted in those numerous, large, old-fashioned, square-galleried inn-yards; and reflect upon the hundreds who have been thrown out of bread. The high-roads and the way-side inns are now forsaken and silent. These remarks are not made merely to show that there is an analogy between the several districts and employments in the metropolis, and those of the country. If this were all, not another word would be written. But it so happens that the comparison affords an opportunity, which cannot be passed over, of referring to the changes which are going on in the world; and forcibly reminds us, that while some are rising, others are falling, and many are in the mire, trodden under foot, and forgotten. It is with the miserable beings who are in the last predicament, that poor-laws have to do.

The political economist may be right when he announces, that the introduction of machinery has, on the whole, been beneficial; and that the change of employment from one locality to another, depends upon the action of natural laws, of which he is merely the expositor. It may be the case, too, that he is attending carefully to the particular limits of his favourite science, when he occupies his mind with the laws themselves, rather than with their aberrations. But those who treat upon pauperism as an existing evil, to be dealt with now, should remember that they have to do not with natural laws, as they are separated and classified in the works of scientific men, but with the laws in all their complexity of operation, and with the incidents which arise from that complexity.

The coachmen, the guards, the ostlers, the horse-keepers, the harness-makers, the farriers, the various workers in the trade of coach-builders, and the crowd of tatterdemalions who performed all sorts of offices, – where are they? The inquirer must go into the back streets and alleys of London. He must search the records of benevolent institutions; and he must hold frequent converse with those who administer parochial relief. But his sphere must not be confined to the metropolis. Let the reader unroll his library map of England, and devote an entire afternoon to the study of it. Trace the high-roads with a pointer. Pause at every town, and at every stage. Refer to an old book of roads, and to a more modern conveyance directory. Let memory perform its office: reflect upon the crowds of persons who gained a subsistence from the fact that yourselves and many others were obliged to travel along the high-road on your way from London to York. There were inn-keepers, and waiters and chambermaids, post-boys and “boots.” Then there were hosts of shop-keepers and tradesmen who were enabled to support their families decently, because the stream of traffic flowed through their native towns and villages. Take a stroll to Hounslow. Its very existence may be traceable to the fact that it is a convenient stage from London. It was populous and thriving, and yet it is neither a town, a parish, nor a hamlet. Enter the bar of one of the inns, and take nothing more aristocratic than a jug of ale and a biscuit. Lounge about the yard, and enter freely into conversation with the superannuated post-boys who still haunt the spot. You will soon learn, that it is the opinion of the public in general, and of the old post-boys in particular, that the nation is on the brink of ruin; and they will refer to the decadence of their native spot as an instance. The writer was travelling, not many months ago, in the counties of Rutland, Northampton, and Lincoln; and while in conversation with the coachman, who then held up his head as high, and talked as familiarly of the “old families,” whose mansions we from time to time left behind us, as if the evil days were not approaching, our attention was arrested by the approach of a suite of carriages with out-riders, advancing rapidly from the north. An air of unusual bustle had been observed at the last way-side inn. A waiter had been seen with a napkin on his arm, not merely waiting for a customer, but evidently expecting one, and of a class much higher than the travelling bagmen: and this was a solitary way-side inn. We soon learnt that the cortège belonged to the Duke of – . The coachman added, with a veneration which referred much more to his grace’s practice and opinions than to his rank, – “He always travels in this way, – he is determined to support the good old plans,” and then, with a sigh, continued, “It’s of no use – it’s very good-natured, but it does more harm than good; it tempts a lot of people to keep open establishments they had better close. It’s all up.”

It is not necessary to pursue this matter further. Nor is it required that we should follow these unfortunates who have thus been thrown out of bread, or speculate upon their fallen fortunes. Nor need we specially remind the reader, that this is only one of many changes which have come upon us during the last quarter of a century, and which are now taking place. Space will not permit a full exposure of the common fallacy, that men soon change their employments. As a general rule, it is false. The great extent to which the division of labour is carried, effectually prevents it. Each trade is divided into a great many branches. Each branch, in large manufactories, is again divided. A youth selects a branch, and by being engaged from day to day, in the same manipulation, he acquires, in the course of years, an extraordinary degree of skill and facility of execution. He works on, until the period of youth is beginning to wane; and then his particular division, or branch, or trade, is superseded. Is it not clear that the very habits he has acquired, his very skill and facility in the now obsolete handicraft, must incapacitate him for performing any other kind of labour, much less competing with those who have acquired the same skill and facility in those other branches or trades?

The most important preliminary inquiry connected with an improved and extended form of out-door relief is, how can the mass of pauperism be broken up and prepared for operation? We are told that the total number of persons receiving relief in England and Wales is 1,470,970, of which 1,255,645 receive out-door relief. Without admitting the strict accuracy of these figures, we may rest satisfied that they truly represent a dense multitude. It is the duty of the relieving officers to make themselves acquainted with the circumstances of each of these cases, and to perform other duties involving severe labour. The number of relieving officers is about 1310. This mass is broken up and distributed among these officers, not in uniform numerical proportion, but in a manner which would allow space and number to be taken into account. The officer who is located in a thickly populated district, has to do with great numbers; while the officer who resides in a rural district, has to do with comparative smallness of numbers, but they are spread over a wide extent of country. The total mass of pauperism is thus divided and distributed; but division and distribution do not necessarily involve classification, and they ought not to be regarded as substitutes for it.

To the general reader, the idea of the classification of the many hundreds of thousands of paupers, and the uniform treatment of each class according to definite rules, may appear chimerical. To him we may say, Look at the enormous amount of business transacted with precision in a public office, or by a “City firm” in a single day. All is done without noise or bustle. There is no jolting of the machinery, or running out of gear. There is that old house in the City. It has existed more than a hundred years. And it has always transacted business with a stately and aristocratic air, – reminding us of Florence and Venice, and the quaint old cities of Ghent and Bruges. The heads of the house have often changed. One family passed into oblivion. Another, when nature gave the signal, bequeathed his interests and powers to his heirs, who now reign in his stead. But, however rapid, or however complete the revolutions may have been, no sensible interruption occurred in the continued flow of business. The principles of management have apparently been the same through the whole period. Yet, as times changed, as one market closed and another opened, as new lands were discovered, trading stations established and grew into towns, as the Aborigines left the graves of their fathers, and retired before the advance of civilisation, and as India became English in its tastes and desires, so did the business and resources of the old house expand, and its machinery of management change. Once in a quarter of a century, a group of sedate looking gentlemen meet in the mysterious back-parlour; a few words are spoken, a few strokes of the pen are made, a few formal directions are given to the heads of departments, a new book is permitted, an addition to the staff is confirmed, and the power of the house is rendered equal to the transaction of business in any quarter of the world, and to any amount. Now, look at this great house of business from the desk. Study the machinery. A young man, perhaps the eldest son of a senior clerk, enters the house, and takes his seat at a particular desk: and there he remains until superannuation or death leaves a vacancy, when he changes his place, from this desk to that, and so on, until old age or death creeps upon him in turn. He is chained daily to the desk’s dull wood, and makes entry after entry in the same columns of the same book. This is his duty. He may be unsteady, irregular, inapt, or incorrect, and his being so may occasion his brethren some trouble, and draw down upon himself a rebuke from a higher quarter; but the machinery goes on steadily notwithstanding. Each clerk, or each desk, has its apportioned duty, which continued repetition has rendered habitual and mechanical. In the head’s of departments, a greater degree of intellect may appear necessary. It is hardly the fact, however. For the head of the department has passed through every grade – he has laboured for years at each desk, and knows intuitively, as it were, the possible and probable errors. His discernment or judgment is a spontaneous exercise of memory, and resembles the chess-playing skill of one who plays a gambit. Now, what is all this? It is called “official routine.” It appears, then, that an extensive business may be transacted steadily and successfully, providing always that a few general rules are laid down, and steadily adhered to, and enforced. In books these rules are simplified, classified, and rendered permanent. A book-keeper may imagine that thousands of voices are above him and around him, giving orders and directions, and admonishing to diligence, and accuracy, – all of which are restrained, subdued, and silenced, and yet all are still speaking, without audible utterance, from the pages before him. And in strictness, it would not be a flight of imagination, but a mode of stating a truth which, from its obviousness, has escaped observation. Of course, these books may speak incoherently and discursively, just as the human being will do; and if they do speak, thus the evils which arise are apt to be perpetuated. The books, then, must have a large share of attention, and be carefully arranged. Then they must have a keeper, and his duties must be explicitly stated, and his character and his means of subsistence made dependent upon his accuracy and vigilance. There is then the choice of the person who is to perform the business which the books indicate and record. The requirements vary in different occupations. In one, strict probity is a grand point; in another, strict accuracy as to time, or skill in distinguishing fabrics and signatures. In some cases, firmness, mildness, and activity, under circumstances of excitement, is required; and these qualities, among others, would appear to be indispensable in parochial and union officers, – if the fact of their oversight did not render it doubtful. The last lesson we learn is, that business should be checked as it proceeds. There are two methods. The one is a system of checks, and is practicable when the business does not occupy much space. The other is a system of minute inspection; there are cases in which both methods may be partially applied, and that of poor-law administration is one of them.

The machinery by which pauperism may be efficiently dealt with, may be thus generally expressed. There would be required: —

First, A Board of Guardians, elected according to law, and with powers and duties defined and limited by legal enactment.

Second, A staff of efficient officers.

Third, A scroll of duties.

Fourth, A set of books, drawn up by men of scientific ability, and submitted to the severest scrutiny of practical men.

Fifth, A system of inspection under the immediate control of the government.

Sixth, District auditors, whose appointment and duties are regulated by the law.

Seventh, And in the negative, the absence of any speculative, interfering, disturbing, and irritating power, which may be continually adding to, varying and perplexing the duties and the management, in attempting to carry into practical operation certain crotchets, and in rectifying resulting blunders.

Much might be said upon each of these requisitions. But we propose rather to limit our remarks, and to turn them in that direction which will afford opportunities for exhibiting the various classes and varieties of poor, and suggesting modes of treatment.

The books which are necessary to enable the several boards of guardians to deal with each individual case, not only as regards the bare fact of destitution, but also with reference, to its causes and remedies, are the Diary or Journal, and the Report Book. The Diary is simple, and may be easily constructed to suit the circumstances of each locality. Every person who has any business to transact, and values punctuality, possesses a Diary, which is drawn up in that form which appears most suitable to his peculiar business or profession. In it is entered the whole of his regular engagements for the day or year, and also those which he makes from day to day. Then on each day, he regularly, and without miss, consults his remembrancer, and learns from thence his engagements for the time being, and so arranges his proceedings. Such a book, drawn up in a form adapted to the nature of the business transacted, and ruled and divided in a manner which a month’s experience would suggest, would be, the Diary. It would differ from that raised by the man of ordinary business in the respect that its main divisions would not be daily, but weekly or fortnightly, according as the board held its meetings. It would be kept by the relieving officer, and laid before the Chairman at each Board meeting – it is in fact a “business sheet.” The name of each poor person who appears before the Board, and with respect to whom orders are made, would appear in this book on each occasion. And the arrangements of its contents would depend upon the classification of the poor.

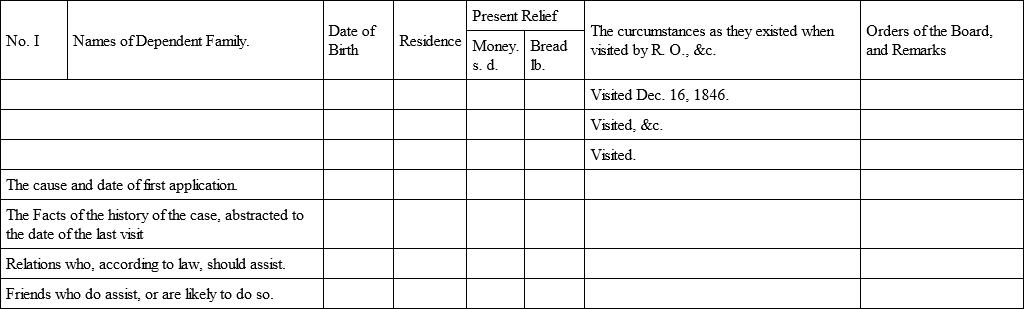

The Report Book1 was briefly commented upon in a former article. Its size should be ample – for it is presumed that each page will record the results of many visits, and be referred to on each occasion that the pauper appears before the Board. The lapse of time between the first entry and the last, may be seven or even ten years.

PROPOSED FORM OF THE RELIEVING OFFICER’S REPORT BOOK

This report is prepared from the actual visit of the relieving officer at the home of the applicant, and by coincidental inquiry. Upon its first reading, there would appear the names of the heads of the family – the names of their children who may be dependent upon them, and the several dates of birth, the residence, the occupation of the several members of the family, their actual condition, the admitted cause of the application for relief, and a statement of such facts as a single visit may disclose respecting their past history. This would form a basis for a future report, and would lead the guardians to make comparisons, and judge whether the case is rising or falling, having reference not only to weeks, but years. The practical man will perceive, that the chief point of difference between this form of Report Book and that enforced by the Commissioners, is, that the latter speaks of the present only, while the proposed form speaks of the past as well, – an addition of vital importance, if character is to be considered. It is clear, if the past and present condition of the applicant be stated, together with the main facts of his history, the mental act of classification will follow inevitably, and will require merely the mechanical means of expression. It may be stated generally with reference to this book: First, Every case must be visited, and reported upon by a statement of facts, not opinions. Second, The report must be made returnable on a given day – this would be secured by the Chairman’s Diary. Third, Each applicant must appear personally before the Board, unless distance or infirmity prevent.

With these books in our possession, we may begin to separate the poor into masses, and collect them into groups. The facts contained in the Report Book would enable Boards of Guardians to decide in which class the applicants ought to be placed. But in order to preserve the classes in their distinctness, a ready and simple mode of grouping them in a permanent manner must be devised; and as it is desirable that old and existing materials should be used in preference to new, the “Weekly Out-Door Relief List,” now in daily use, may be made the basis of an improved form.2

How are we to proceed? Let the reader call to mind a parish or union with which he is acquainted, and make it the scene of his labours. That period of the year when the demands upon the attention of the Board of Guardians, and its officers, are at zero, may be selected for making the first step in advance. The most convenient season of the year would probably be a late Easter; for at that time the weekly returns for in-door and out-door relief are rapidly descending. The winter is losing its rugged aspect and is rapidly dissolving into spring: and labour is busy in field and market. And so it continues until the fall of the year, except when the temperature of the summer may be unusually high, and then low fever and cholera prevail in low, marshy, crowded, or undrained districts. Those cases which have received relief for the longest period may be taken first. The technicalities of the report may be made up from existing documents. The history of each case may not be so readily prepared. It being a collection of facts, they may be added slowly. The space allotted to this important matter is amply sufficient, unless the officer should unfortunately be afflicted with a plethora of words. The whole number of ordinary cases may be reported upon, and their classes apportioned, before the winter sets in. In the month of November, the medical list would begin to be augmented. And as the dreary season for the poor advances, the casual applications would multiply. In two or three years the names of all persons who ordinarily receive relief, or are casually applicants, would be found in the Report Book: and the facts having been recorded there, the labours of the officer would then decrease, and be confined to the investigation of existing circumstances.