Полная версия:

Various Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Vol. 66, No 409, November 1849

- + Увеличить шрифт

- - Уменьшить шрифт

Various

Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Vol. 66, No 409, November 1849

THE TRANSPORTATION QUESTION

The great question of Secondary Punishments has now been settled by experience, so far as the mother country is concerned. It is now known that imprisonment has no effect whatever, either in deterring from crime, or in reforming criminals. Government, albeit most unwilling to recur to the old system of transportation, has been compelled to do so by the unanimous voice of the country; by the difficulty of finding accommodation for the prodigious increase of prisoners in the jails of the kingdom; and by the still greater difficulty, in these days of cheapness and declining incomes, of getting the persons intrusted with the duty of providing additional prison accommodation, to engage in the costly and tedious work of additional erections. An order in council has expressly, and most wisely, authorised a return to transportation, under such regulations as seem best calculated to reform the convicts, and diminish the dread very generally felt in the colonies, of being flooded with an inundation of crime from the mother country. And the principal difficulty felt now is, to find a colony willing to receive the penal settlers, and incur the risks thought to be consequent on their unrestricted admission.

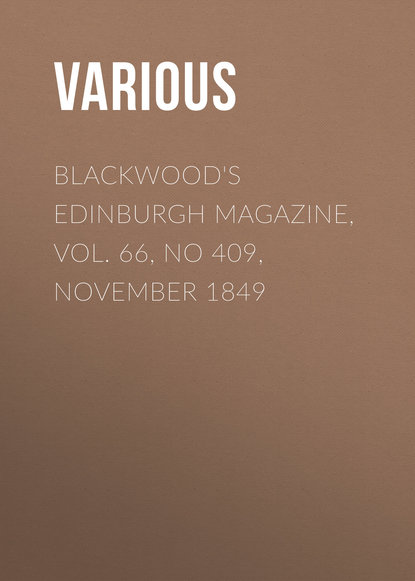

It is not surprising that government should have been driven from the ruinous system of substituting imprisonment for transportation; for the results, even during the short period that it was followed out, were absolutely appalling. The actual augmentation of criminals was the least part of the evil; the increase of serious crimes, in consequence of the hardened offenders not being sent out of the country, but generally liberated after eighteen months' or two years' confinement, was the insupportable evil. The demoralisation so strongly felt and loudly complained of in Van Diemen's Land, from the accumulation of criminals, was rapidly taking place in this country. The persons tried under the aggravation of previous convictions in Scotland, in the three last years, have stood as follows: —

– Parliamentary Reports, 1846-48.

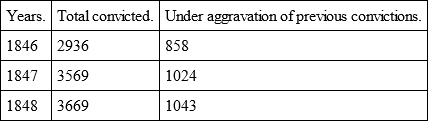

So rapid an increase of crimes, and especially among criminals previously convicted, sufficiently demonstrates the inadequacy of imprisonment as a means either of deterring from crimes, or reforming the criminals. The same result appears in England, where the rapid increase of criminals sentenced to transportation, within the same period, demonstrates the total inefficacy of the new imprisonment system.

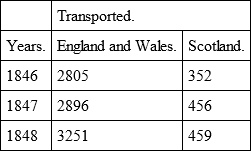

And of the futility of the hope that the spread of education will have any effect in checking the increase of crime, decisive proof is afforded in the same criminal returns; for from them it appears that the number of educated criminals in England is above twice, in Scotland above three times and a half that of the uneducated, – the numbers, during the last three years, being as follows: —

– Parliamentary Returns, 1846-8.

Nay, what is still more alarming, it distinctly appears, from the same returns, that the proportion of educated criminals to uneducated is steadily on the increase in Great Britain. Take the centesimal proportions given in the last returns for England – those of 1848: —

– Parliamentary Returns for England, 1848, p. 12.

The great increase here is in the criminals who have received an imperfect education, which class has increased as much as that of the totally uneducated has diminished. Unhappily, imperfect education is precisely the species of instruction which alone, in the present days of cheapened production and diminishing wages, the great body of the poor are able to give to their children.

Mr Pearson, M.P., who has paid great attention to this subject, and whose high official situation in the city of London gives him such ample means of being acquainted with the practical working of the criminal law, has given the following valuable information in a public speech, which every one acquainted with the subject must know to be thoroughly well founded: —

"In the year 1810, which is the earliest account that we possess in any of our archives, the number of commitments, of assize and sessions cases, was 5146. In the year 1848, the number of commitments for sessions and assize cases was 30,349. Population during that period had increased but 60 per cent, whilst the commitments for crime had increased 420 per cent. I should not be candid with this assembly if I did not at once say, that there are various disturbing circumstances which intervene, during that period, to prevent the apparent increase of commitments being the real estimate of the actual increase. There was the transition from war to peace. We all know, that from the days of Hollingshed, the old chronicler, it has been said that war takes to itself a portion of the loose population, who find in the casualties of war, its dangers, rewards and profligate indulgences, something like a kindred feeling to the war made upon society by the predatory classes. Hence we find that, when war ceases, a number of that class of the community are thrown back on the honest portion of society, which, during the period of war, had been drained off. Besides this, there are other co-operating causes. There is the improved police, the constabulary, rural or metropolitan, who undoubtedly detect many of those offences which were formerly committed with impunity. There is also the act of parliament for paying prosecutors and witnesses their expenses, which led to an increased number of prosecutors in proportion to the number of crimes actually detected. These circumstances have, no doubt, exercised a considerable influence over the increase in the commitments; but after having for 35 years paid the closest attention to the subject, having filled, and still filling, a high office in regard to the administration of the law in the city of London, I am bound to say, that, making full deduction from the number which every feeling of anxiety to raise the country from the imputation of increasing in its criminal character dictates – after making every deduction, I am bound with shame and humility to acknowledge, that it leaves a very large amount of increase in the actual, the positive number of commitments for crime. Sir, this is indeed a humiliating acknowledgment; but happily the statistics of this country, in other particulars, warrant us in drawing comfort from the conviction, that even this fact affords no true representation of the state of the moral character of the people – no evidence of their increasing degradation of character or conduct, in anything like the proportion or degree that those statistics would appear to show. I appeal to history – I appeal to the recollection of every man in this assembly, who, like myself, has passed the meridian of life, whether society has not advanced in morals as well as in arts, science, and literature, and everything which tends to improve the social character of the people. Let any man who has read not our country's history alone, but the tales and novels of former times – and we must frequently look to them, rather than to the records of history, for a faithful transcript of the morals of the age in which they were written, – let any man recur to the productions of Fielding and of Smollett, and say whether the habits, manners, and morals of the great masses of our population are not materially improved within the last century. Great popular delusions prevail as to the causes of the increase of commitments for criminal offences in this country, which I deem it to be my duty to endeavour to dispel. Some ascribe the increase to the want of instruction of our youth, some to the absence of religious teaching, some to the increased intemperance, and some to the increased poverty of the people. I assert that there is no foundation for the opinions that ascribe the increase of crime to these causes. If the absence of education were the cause of crime, surely crime would be found to have diminished since education has increased. For the purpose of comparing the present and past state of education, for its influence upon the criminal statistics of the nation, I will not go back to the time when the single Bible in the parish was chained to a pillar in the church; or when the barons affixed their cross to documents, from inability to write their names. I refer to dates, and times, and circumstances within our own recollection. In the year 1814 the report of the National Society says, there were only 100,000 children receiving the benefit of education. Now there are above 1,000,000 under that excellent institution, besides the tens of thousands and hundreds of thousands who are receiving education under the auspices of the Lancasterian Society Schools. But some may say that the value of education is not to be estimated by numbers. Well then, I reject numbers, if you please, and try it by its quality. I ask any man who listens to me if he does not know that the national schools, and other gratuitous establishments in this country, now give privileges in education which children in a respectable condition of life could hardly obtain, such was the defective state of instruction in this country, 40 or 50 years ago. (Cheers.) No man, therefore, can say that the increase of crime is attributable to the absence of education. If it were so, with education increased 800 per cent during the last 30 years, crime would have diminished, instead of increased, 400 per cent." —Times, Aug. 28, 1849.

The immense expense with which the maintenance of such prodigious numbers of prisoners in jail is attended, is another most serious evil, especially in these days of retrenchment, diminished profits, and economy. From the last Report of the Jail Commissioners for Scotland – that for 1848 – it appears that the average cost of each prisoner over the whole country for a year, after deducting his earnings in confinement, is £16, 7s. 6d. As this is the cost after labour has been generally introduced into prisons, and the greatest efforts to reduce expense have been made, it may fairly be presumed that it cannot be reduced lower. The average number of prisoners constantly in jail in Scotland is now about 3500, which, at £16, 7s. 6d. a-head, will come to about £53,000 a-year.1 Applying this proportion to the 60,000 criminals, now on an average constantly in confinement in the two islands,2 the annual expense of their maintenance cannot be under a million sterling. The prison and county rates of England alone, which include the cost of prosecutions, are £1,300,000 a-year. But that result, enormous as it is in a country in which poor-rates and all local burdens are so rapidly augmenting, is but a part of the evil. Under the present system a thief is seldom transported, at least in Scotland, till he has been three or four years plying his trade; during which period his gains by depredations, and expenses of maintenance, cannot have averaged less than £25 yearly. Thus it may with safety be affirmed, that every thief transported from Scotland has cost the country, before he goes, at least £100; and that has been expended in training him up to such habits of hardened depravity, that he is probably as great a curse to the colony to which he is sent, as he had proved a burden to that from which he was conveyed. Sixteen pounds would have been the cost of his transportation in the outset of his career, when, from his habits of crime not being matured, he had a fair chance of proving an acquisition, instead of a curse, to the place of his destination.

As the question of imprisonment or transportation, so far as Great Britain and Ireland are concerned, is now settled by the demonstrative evidence of the return of a reluctant government to the system which in an evil hour they abandoned, it may seem unnecessary to go into detail in order to show how absolutely necessary it was to do so; and how entirely the boasted system of imprisonment, with all its adjuncts of separation, silence, hard labour, and moral and religious instruction, has failed either in checking crime, or producing any visible reformation in the criminals. No one practically acquainted with the subject ever entertained the slightest doubt that this would be the case; and in two articles directed to the subject in this magazine, in 1844, we distinctly foretold what the result would be.3 To those who, following in the wake of prelates or philanthropists, how respectable soever, such as Archbishop Whately, who know nothing whatever of the subject except from the fallacious evidence of parliamentary committees, worked up by their own theoretical imaginations, we recommend the study of the Tables below, compiled from the parliamentary returns since the imprisonment system began, to show to what a pass the adoption of their rash visions has brought the criminal administration of the country.4

It is not surprising that it should be so, and that all the pains taken, and philanthropy wasted, in endeavouring to reform criminals in jail in this country, or hindering them from returning to their old habits when let loose within it, should have proved abortive. Two reasons of paramount efficacy have rendered them all nugatory. The first of these is, that the theory regarding the possibility of reforming offenders when in prison, or suffering punishment in this country, is wholly erroneous, and proceeds on an entire misconception of the principles by which alone such a reformation can in any case be effected. In prison, how solitary soever, you can work only on the intellectual faculties. The active powers or feelings can receive no development within the four walls of a cell, for they have no object by which they can be called forth. But nine-tenths of mankind in any rank, and most certainly nineteen-twentieths of persons bred as criminals, are wholly inaccessible to the influence of the intellect, considered as a restraint or regulator of their passions. If they had been capable of being influenced in that way, they would never have become criminals. Persons who fall into the habits which bring them under the lash of the criminal law, are almost always those in whom, either from natural disposition, or the unhappy circumstances of early habits and training, the intellectual faculties are almost entirely in abeyance, so far as self-control is concerned; and any development they have is only directed to procuring gratification for, or furthering the objects of the senses. To address to such persons the moral discipline of a prison, however admirably conducted, is as hopeless as it would be to descant to a man born blind on the objects of sight, or to preach to an ignorant boor in the Greek or Hebrew tongue. Sense is to them all in all. Esau is the true prototype of this class of men; they are always ready to exchange their birthright for a mess of pottage.

No length of solitary confinement, or scarce any amount of moral or religious instruction, can awaken in them either the slightest repentance for their crimes, or the least power of self-control when temptation is again thrown in their way. They regard the period of imprisonment as a blank in their lives – a time of woful monotony and total deprivation of enjoyment, which only renders it the more imperative on them, the moment it is terminated, to begin anew with fresh zest their old enjoyments. Their first object is to make up for months of compulsory sobriety by days of voluntary intoxication. At the close of a short period of hideous saturnalia, they are generally involved in some fresh housebreaking or robbery, to pay for their long train of indulgence; and soon find themselves again immured in their old quarters, only the more determined to run through the same course of forced regularity and willing indulgence. They are often able to feign reformation, so as to impose on their jailors, and obtain liberation on pretended amendment of character. But it is rarely if ever that they are really reclaimed; and hence the perpetual recurrences of the same characters in the criminal courts; till the magistrates, tired of imprisoning them, send them to the assizes or quarter-sessions for transportation. Even then, however, their career is often far from being terminated in this country. The keepers of the public penitentiaries become tired of keeping them. When they cannot send them abroad, their cells are soon crowded; and they take advantage of a feigned amendment to open the prison doors and let them go. They are soon found again in their old haunts, and at their old practices. At the spring circuit held at Glasgow in April 1848, when the effects of the recent imprisonment mania were visible, – out of 117 ordinary criminals indicted, no less than twenty-two had been sentenced to transportation at Glasgow, for periods not less than seven years, within the preceding two years; and the previous conviction and sentence of transportation was charged as an aggravation of their new offence against each in the indictment.

The next reason which renders imprisonment, in an old society and amidst a redundant population, utterly inefficacious as a means of reforming criminals is, that, even if they do imbibe better ideas and principles during their confinement, they find it impossible on their liberation to get into any honest employment, or gain admission into any well-doing circle, where they may put their newly-acquired principles into practice. If, indeed, there existed a government or parochial institution, into which they might be received on leaving prison, and by which they might be marched straightway to the nearest seaport, and there embarked for Canada or Australia, a great step would be made towards giving them the means of durable reformation. But as there is none such in existence, and as they scarcely ever are possessed of money enough, on leaving prison, to carry them across the Atlantic, they are of necessity obliged to remain in their own country – and that, to persons in their situation, is certain ruin. In new colonies, or thinly-peopled countries, such as Australia or Siberia, convicts, from the scarcity of labour, may in general be able to find employment; and from the absence of temptation, and the severance of the links which bound them to their old associates, they are often there found to do well. But nothing of that sort can be expected in an old and thickly-peopled country, where the competition for employment is universal, and masters, having the choice of honest servants of untainted character, cannot be expected to take persons who have been convicted of crimes, and exposed to the pollutions of a jail.

Practically speaking, it is impossible for persons who have been in jail to get into any honest or steady employment in their own country; and if they do by chance, or by the ignorance of their employers of their previous history, get into a situation, it is ere long discovered, by the associates who come about them, where they have been, and they speedily lose it. If you ask any person who has been transported in consequence of repeated convictions, why he did not take warning by the first, the answer uniformly is, that he could not get into employment, and was obliged to take to thieving, or starve. Add to this that the newly-reformed criminal, on leaving jail, and idling about, half starved, in search of work, of necessity, as well as from inclination, finds his way back to his old residence, where his character is known, and he is speedily surrounded by his old associates, who, in lieu of starving integrity, offer him a life of joyous and well-fed depravity. It can hardly be expected that human virtue, and least of all the infant virtue of a newly-reformed criminal, can withstand so rude a trial. Accordingly, when the author once asked Mr Brebner, the late governor of the Glasgow bridewell, what proportion of formed criminals he ever knew to have been reformed by prison discipline, he answered that the proportion was easily told, for he never knew one. And in the late debate in parliament on this subject, it was stated by the Home Secretary, Sir George Grey, that while the prison discipline at Pentonville promised the most cheering results, it was among those trained there, and subsequently transported, that the improvement was visible; for that no such results were observed among those who, after liberation, were allowed to remain in this country.

But while it is thus proved, both by principle and experience, that the moral reformation of offenders cannot be effected by imprisonment, even under the most improved system, in this country, yet, in one respect, a very great amelioration of the prisoner's habits, and extension of his powers, is evidently practicable. It is easy to teach a prisoner a trade; and such is the proficiency which is rapidly acquired by the undivided attention to one object in a jail, that one objection which has been stated to the imprisonment system is, that it interferes with the employment of honest industry out of doors. No one can walk through any of the well-regulated prisons in Great Britain without seeing that, whatever else you cannot do, it is easy to teach such a proficiency in trade to the convicts as may render them, if their depraved inclinations can be arrested, useful members of society, and give them the means of earning a livelihood by honest industry. Many of them are exceedingly clever, evince great aptitude for the learning of handicrafts, and exert the utmost diligence in their prosecution. Let no man, however, reckon on their reformation, because they are thus skilful and assiduous: turn them out of prison in this country, and you will soon see them drinking and thieving with increased alacrity, from the length of their previous confinement. It is evidently not intellectual cunning, or manual skill, or vigour in pursuit, which they in general want – it is the power of directing their faculties to proper objects, when at large in this country, which they are entirely without, and which no length of confinement, or amount of moral and religious instruction communicated in prison, is able to confer upon them. Here then is one great truth ascertained, by the only sure guide in such matters —experience– that while it is wholly impossible to give prisoners the power of controlling their passions, or abstaining from their evil propensities, when at large, by any amount of prison discipline, it is always not only possible, but easy, to communicate to them such handicraft skill, or power of exercising trades, as may, the moment the wicked dispositions are brought under control, render them useful and even valuable members of society.

Experience equally proves that, though the moral reformation of convicts in this country is so rare as, practically speaking, to be considered as impossible, yet this is very far indeed from being the case when they are removed to a distant land, where all connexion with their old associates is at once and for ever broken; where an honest career is not only open, but easy, to the most depraved, and a boundless supply of fertile but unappropriated land affords scope for the exercise of the desire of gain on legitimate objects, and affords no facilities for the commission of crime, or the acquisition of property, by the short-hand methods of theft or robbery. Lord Brougham, in a most able work, which is little known only because it runs counter to the prejudices of the age, has well explained the causes of this peculiarity: —

"The new emigrants, who at various times continued to flock to the extensive country of America, were by no means of the same description with the first settlers. Some of these were the scourings of jails, banished for their crimes; many of them were persons of desperate fortunes, to whom every place was equally uninviting; or men of notoriously abandoned lives, to whom any region was acceptable that offered them a shelter from the vengeance of the law, or the voice of public indignation. But a change of scene will work some improvement upon the most dissolute of characters. It is much to be removed from the scenes with which villany has been constantly associated, and the companions who have rendered it agreeable. It is something to have the leisure of a long voyage, with its awakening terrors, to promote reflection. Besides, to regain once more the privilege of that good name, which every unknown man may claim until he is tried, presents a powerful temptation to reform, and furnishes an opportunity of amendment denied in the scenes of exposure and destruction. If the convicts in the colony of New Holland, though surrounded on the voyage and in the settlement by the companions of their iniquities, have in a great degree been reclaimed by the mere change of scene, what might not be expected from such a change as we are considering? But the honest acquisition of a little property, and its attendant importance, is, beyond any other circumstance, the one most calculated to reform the conduct of a needy and profligate man, by inspiring him with a respect for himself and a feeling of his stake in the community, and by putting a harmless and comfortable life at least within the reach of his exertions. If the property is of a nature to require constant industry, in order to render it of any value; if it calls forth that sort of industry which devotes the labourer to a solitary life in the open air, and repays him not with wealth and luxury, but with subsistence and ease; if, in short, it is property in land, divided into small portions and peopled by few inhabitants, no combination of circumstances can be figured to contribute more directly to the reformation of the new cultivator's character and manners."5