Oleg Krasin

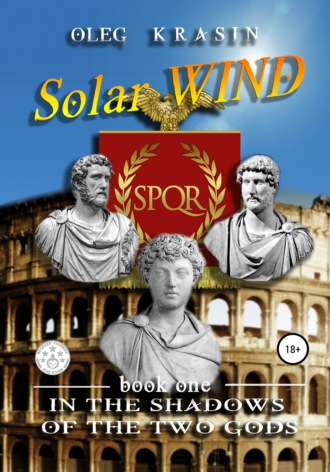

Solar Wind. Book one

Marcus broke away from reading, hesitantly looking at his mother. She made a permitting gesture with her hand, and they all went to the entrance to the imperial baths. In a large room lined with black-and-white floor slabs, columns of Corinthian pink marble towered around the perimeter, and in the niches the sculptures of Venus and Cupid, who took frivolous poses, took refuge. In the center was a pool in which the blue water splashed.

“Hadrian banned the joint washing of women and men,” Sabine remarked, smiling playfully. “But we're all here. Aren’t we?”

She threw off the tunic, exposing the taut, slender body of the nulliparous woman and began to slowly descend the steps into the water. She felt Marcus studying her, and therefore she was in no hurry. Domitia also followed her example, however, not too much embarrassed—they used to bathe with their son at home.

“Come on, Marcus. Come join us!” Sabina called, turning to him in the water so that he could see her all, from the breasts to the tips of feet. “Don't stand like a statue!”

Marcus undressed and, turning to give clothes to the slave, noticed two African slaves standing nearby. Those with their hands folded on their stomachs, looked indifferently in front of them, like two living idols motionlessly frozen on the order of the lady.

Dog philosophy

The villa of his parents, where Marcus lived, was located on Caelius near Regin's house. It was one of the seven hills of the city, which had long been favored by the Roman nobility. The area became fashionable among patricians because of the picturesque and sparsely populated area. There was no crowding nor the crowds of the big city, here they did not hear the noise and cries of the crowd, nor the disgusting smells of Roman streets.

From the height of the hill, Marcus had more than once seen the splendor of the world capital, seeing the giant Flavius Amphitheatre, the beginning of the forum resting on the Capitol, the new thermae of Trajan. The view of Rome, mighty, beautiful, irresistibly stretching upwards, as a living organism grows—conquering the peaks and forever crashing into his memory. He would remember many times his Caelius, mighty oaks crowding on the slopes, air full of the bloom of spring and youth, warm sun overhead.

Marcus’s great-grandfather Regin told him that one of the famous Roman generals, the winner of Hannibal Scipio Africanus with his cohorts, stayed on Caelian Hill. Here he marched triumphant, proud of his victories in the glory of Rome, dragged after the carts with gold and prisoners of the captured lands. Great-grandfather tried to instill in Marcus a deep pride for Rome, and what best makes one proud than the victory of ancestors?

Oh, this hill of Caelian Marcus would always remember.

Much connected him to this hill. Here, in his parents' villa, he grew up under the care of his mother. Father, Annius Verus, after whom Marcus took his name, died early, and he remembered him vaguely. Actually, there were only two fragments of memories remaining; the father in iron armor and purple cloak beside his mother, holding her hand, and the second…

Father walks in the garden near the villa. He's in a white toga. It is early morning and sunlight, like a waterfall flowing from a clear blue sky, completely fills the garden. From the humid ground slowly rises the milky mist, absorbing brown trunks, green branches, leaves and gradually concealing the father. His white toga merges with white smoke, as if the figure of Marcus Annius Verus is removed deep into the garden. Marcus seems to see that he sees a colorful picture, which is filled with milk. It is as if the spirits of the garden seek to hide his father to spite him. The fog is stronger and higher. He sees his father’s waist, his chest, and his head, but then he completely disappears behind a dense shroud …

However, Marcus felt implicit gratitude to his parents for his masculinity, for the fact that he loved his mother, did not offend her. Perhaps that is why she did not marry, although the women of her circle, remaining widows, did not remain faithful to the dead for long. And some divorced their living husbands, remarrying three or four times. Such actions in Rome were not condemned, but rather were usual.

Here on the Caelian Hill, as his great-grandfather did not recognize the benefits of public school, Marcus's homeschooling began.

Music was taught to him by the Greek Citharode20 Andron, with whom Marcus also learned geometry. Musician-geometer, what could have been weirder? But amazing people often met a curious boy. Or maybe he saw the unusual in the fact that the others considered the matter ordinary?

And Marcus studied painting from another strange man, also a Greek, Diognetus.

“Keep your hand softer, don't strain the brush!” Marcus was taught. “Art is like nature, vague strokes replace clear lines, empty space filled with inner air. This is where the mystery is born. Look at the sculptures covered with toga, tables or cloaks. Behind the soft folds is human flesh, the living soul, though wrapped in marble. This secret of revival is incomprehensible and eternal, but we Greeks still prefer the naked body, with the beauty of which nothing can be compared.”

“Didn't the poet Lucian condemn the call?” Marcus, who studied Lucian's grammar satire, asked.

“Nudity does not hide anything, and this is its appeal,” Diognetus concluded.

Marcus looked at the Greek mentor, absorbed, listened, watched. Diognetus taught him a lot. He was not like the grammar teachers of Alexander of Cotiaeum or Titus Prokul. They forced their pupils to read literature, memorize passages from Latin and Greek authors, to make speeches published by them, and then to disassemble. For example, Marcus had to come up with the text of Cato's speech to the Senate. Or an obituary for the Spartan king Leonid, who died in battle with the Persians.

Grammar exercises awakened the imagination, seemed to Marcus interesting, but Diognetus ridiculed them.

This tall, with a large forehead, sinewy artist, in general turned out to be a great skeptic. Marcus suspected that in Greece Diognetus attended a school of cynics21 and therefore wore a long uncombed beard, a simple squalid cloak. Laughing, he said of himself that he lived like a dog and that he was free from possessing useless things. “I am a true dog,” he grinned.

From him, Marcus learned that only strong personalities, heroes who were not afraid of anything but the gods could trust people. That's why the less you trust, the stronger you become. That's the paradox. Especially it is impossible to rely on magicians, on all sorts of fortune-tellers and broadcasters, who are the real charlatans, because they have appropriated the right of predictions belonging only to the Parks.22 “Their spells are a pittance,” Diognetus said of them harshly and mockingly, “they should be driven away like dirty and smelly dogs, plagued sick.”

Learning about Marcus's long-standing addiction to quail breeding, the free artist-philosopher ruthlessly ridiculed this boyish fascination. The harmless birds made him laugh contemptuously. “Philosophers,” he said morally, “don't breed birds, they eat them.”

Yes, Diognetus taught him a lot besides painting. Because of him, Marcus began to eat only bread and sleep on the floor, on hard skins, because his teacher went through it, and so were real Hellenics brought up.

Perhaps the fascination with cynics had gone too far. Like all boys his age, Marcus was too trusting and malleable to someone else's influence. He turned into soft clay in the hands of a Greek sculptor. It would be nice if these hands were worthy, noble, but not the hands of a cynic philosopher.

No, the strict and attentive Domitia Lucilla did not want her child to become a dog. Into a senator, consul, worthy son of Rome—yes. But into a dog—absolutely not! Diognetus's influence on Marcus seemed too aggressive, premature, and ultimately unnecessary.

She turned to Regin, who recognized her arguments quite fairly, and the artist-philosopher was dismissed from training. However, Marcus took the news quite calmly. By that time, he had already gained a youthful fascination with poverty, when the real world, nature looks like the antipode of patrician life and its inherent luxury, when it seems that rational simplicity is a certain meaning, and material poverty does not mean spiritual poverty.

However, the philosophy of the dog Diognetus was not in vain. Somewhere in the back of his mind this philosophy firmly sat, languished, raising difficult questions. She, this philosophy, could be an antidote to the life surrounding him. Just as King Bosporus Mithridates took poison in small doses not to be poisoned, Diognetus's views could relieve the feeling of the hardships and injustices of being.

But not now—the mother decided. Someday in the future, perhaps he would remember the words of the rebel.

Tiburtine Temptations

Bored, Hadrian sometimes sent for Marcus. When this happened, the young man would be brought to a villa near the Tempe Valley in Tibur. Of course, he would always travel with Domitia Lucilla. Masculinity was already awakening in the young man: the first hairs had begun to appear on his face, so far, a barely noticeable fluff, but quite visible on the cheeks. The voice began to grow rougher, and youthful alto sonority gave way to adult male bass. Hands and feet began to pour force, to strengthen, to develop. He cast curious glances in the direction of young girls—slaves and freedwomen, which did not hide from the watchful eye of Hadrian, but caught the secretive interest of Marcus to boy-slaves, and there were many of them in Tibur.

“You are not so simple my Verissimus,” Hadrian said, looking intently at Marcus, “What do you feel when you look at them?”

“What am I looking at?” Marcus didn't understand.

“On the young flesh, on the girls, on the boys. Don't you want to be the owner of these bodies? Take them, to own them? I see your passions raging, but you're secretive, Marcus Annius Verus. Don't hold back, let yourself go. Let go!”

Hadrian pronounced the last words in almost a whisper, leaning toward Marcus's ear, and Marcus smelled the incense that rubbed the emperor’s body, the scent of Paestum roses. Something tickled his ear. Oh, yes, it was Hadrian's beard! Marcus wanted to withdraw, but dared not, because no one knows what can infuriate the ruler of Rome. What if he decided that he smelled bad from his mouth and Marcus was squeamish? Or something like that? Hadrian's mind was unpredictable.

But Hadrian pulled himself away, and Marcus peered into his serious face, blazing with a secret fire in his eyes. These were the eyes of a man tired of life, tired from a lot of seeing, a lot of surviving, a man exhausted by nosebleeds, eyes talking about the inner heat that had not yet been extinguished.

The emperor sat down on a chair, stroking a graying beard, thick, curled into small rings.

Domitia Lucilla told Marcus about that beard. Allegedly, Caesar's face in his youth was spoiled by ugly scars and warts, and to hide his ugliness he grew his facial hair, although before him no ruler of Rome was bearded. He himself declared himself a supporter of Hellenism, an ancient Greek culture, and all the great Greeks, as it was known, were famous for their facial hair. With the exception of Alexander, the Great, perhaps. But Homer, but Thucydides, but Aristotle?

“What am I talking about? About passions.” Hadrian continues. “Let it be known to you, but I have a passion too. One, for life…”

The emperor fell silent, waiting for Marcus's clarifying question, and he did not make himself wait.

“What passion, Caesar?”

“Curiosity, my friend, I am curious, and this is my disease. Because of her, I lost my Antinous.” He blinked his eyes quickly, as if trying to drive away the tears that came running. “I was in Egypt and believed the fortune-telling that the soul of Antinous, so beloved by me, would not leave his body before me. She would ascend to the sky a wonderful star for only a moment, and then would return to earth and breathe life back into it. And my boy, my Antinous, believed it, too.”

Hadrian fell silent as if he found it difficult to speak, as if he were being suffocated by the sobs he had once forcibly restrained in order not to show weakness, and now the moment had finally come. But the emperor did not sob, after a certain pause he continued with a shuddering voice.

“In the evening, Antinous entered the waves of the Nile, and we stood on the shore, raising our heads to the sky. And we saw him, my Antinous. There, in the distant depths of heaven, a new star shone. There was a sign of the gods, the revelation of Jupiter!”

Hadrian looked up to the ceiling lined with colored mosaics depicting the assembly of the all-powerful deities of Rome. There was Jupiter, Juno, Mars, Hercules, and other, less powerful and significant deities. They strolled along the celestial ceiling, treading on the clouds with their heels, as if on the ground.

“What happened next?”

“He didn't come back,” the emperor said dryly, stretching his legs, showing beautiful sandals with golden laces, manicured feet.

Despite his dramatic story, he looked relaxed, lazy, but his eyes continued to blaze with secret fire, sometimes hiding behind centuries, which, like curtains in the theater, covered the turbulent life behind the scenes.

“What does your mother, the venerable Domitia Lucilla, do?” he asked.

“She walks around the portico and then goes to the library.”

“I have all the books in the world.” Hadrian doesn't miss the opportunity to smugly brag. “She'll have something to read. However, she can take my slave. I have good readers. They say you're about to turn fourteen soon?”

“That's right, Caesar!”

“It's time to put on the toga of an adult male. I think it's time! I watched your horoscope and the stars told me it was time. We're going to celebrate this in the next Liberalia spree.”23

The thought of the toga virilis24 hadn’t occurred to Marcus. Usually boys wore it at sixteen, or even later. But the emperor already distinguished him from the rest, so why not become an adult earlier? His mother and great-grandfather would be proud of him.

“I'll talk to Domitia about it,” Hadrian continued. “I hope you don't mind. Now, let's go and visit the thermals. They are my pride. There you will see incredible sea monsters in marble columns and bas-reliefs with newts and nereids.”

He rose, making an inviting hand, and they went to the baths, following the wide slab paths, in the shade of graceful porticos, accompanied by sharp cries of peacocks, which walked importantly on the grass.

In the evening, after a hearty lunch, Marcus retired to his room, the air of which had before refreshed with saffron and cinnamon, and lay down on the bed.

Thoughts, impressions overwhelmed him, because he had never been so close to the emperor. And now he spent his hours with him, listening to amazing stories about Greece, Egypt, Antiochus. Caesar was a great connoisseur of the arts and customs of these countries. Someday, Marcus would be able to sit on a speed galley and go on a journey to see the whole world civilized by the Romans.

It would be his own wanderings and his own impressions. And he too would talk about them, and listeners would also listen to him with burning eyes.

“Are you still awake, Marcus?”

On the doorstep of the room there was the slender figure of his mother. They often did so; Domitia Lucilla came to him before going to bed, sat down by her son's legs, asked about what he cared about, shared herself. These trust filled conversations became a habit for them and may seem strange only to the perverted mind.

Now they were eager to discuss the news related to Marcus's receipt of the toga virilis. For them it was an unexpected mercy of Caesar, although Domitia suspected that it was not without the favorable influence of Sabina. Despite the fact that the couple would quarrel, and for several years the couple did not live under the same roof, Adrian still listened to his wife.

“The emperor likes you very much,” Domitia Lucilla said. “It gives our family the right to hope for future graces. Oh, gods, we must not lose our luck!”

“I swear to Jupiter, I will try, Mother!” Marcus promised embarrassingly, recalling Hadrian's burning eyes.

The obligation given to him by his mother imposed on him a special vow of obedience, but it had clear boundaries. What if Hadrian wanted to see him as Antinous, not a Greek young man, but a Roman? However, Antinous was not as noble as Marcus, and the connection of patrician with the freedman was never forbidden. But Marcus's was different business.

Won't he dishonor the family, disgrace her with his close relationship with Caesar?

He did not convey his anxieties and doubts to his mother. Why bother her? Why put before her and great-grandfather Regin the difficult choice? Although for Regin, probably, there was no dilemma in such a delicate and important issue. Marcus felt that his great-grandfather was ready for anything because of the power, even to sacrifice his grandson or, at least, part of his body.

Moonlight already made its way into the narrow window holes when Domitia Lucilla left her son. She carried away an oil lamp and her wandering light, moving along the corridor further and further, plunging the room into darkness. Only the aroma of Paestum roses still hung in the air—in Hadrian's Palace it was added everywhere, even in oil lamps.

Warm, not yet cooled air penetrated into the room, blowing Marcus, promising him sweet dreams. But he was not sleeping, he was thinking about his talk was his mother. Nearby on the table there was a tray of fruit, he stretched, took the dates, ate.

Suddenly, he felt that apart from the night breeze in the room someone else stood there, someone alive. Were there thieves? But the villa was guarded by the Pretorians. The emperor? Marcus helplessly squeezed into the bed, feeling like he was being thrown into the heat.

In the barely discernible moonlight, he saw a white figure approaching him—large, shapeless, like a huge snowball rolling down a mountain. Once in Rome snow fell, which was a rarity, and Marcus and his friends lowered from the Caelian Hill such ice balls. The snowball was getting closer and almost rolling to the bed, it suddenly split, turning into two, clearly distinguishable people.

No, it was not the emperor!

“Who are you?” he asked barely audibly.

“We are slaves in the villa,” one of the figures replied in a girl's voice. “I'm Benedicta. Theodotus is with me.”

“What do you need?”

“We were sent by a great Caesar. He told us to fulfill all your wishes, master.”

“My desires?” Marcus hesitated.

“Of course!” Benedicta laughed with a soft cooing laugh.

Theodotus at this time lit the lamp and put it on a table next to the fruit. Marcus saw a very young, twelve-year-old black boy dressed in a tunic. Benedicta turned out to be a nice girl, also young and slender. She was a little older than Marcus. He also noticed in one of the walls opposite a subtle light beating from an inconspicuous crack. Or from a hole. Someone was watching them. It was Hadrian understood Marcus.

Marcus immediately recalled the words spoken to him in the morning by Caesar about possession, about passion. Hadrian ordered him to let himself go, with his head immersed into the river of desires. But did he really want Marcus to lose his virginity in Tibur? What if it was a test? Perhaps Hadrian wants to make sure that Marcus was able to own himself in difficult moments when he was subjected to temptations that not every mortal can withstand? After all, Hadrian was almost a god, who could control passions. Even his connection with Antinous did not look mad against the background of the orderly and leisurely life that this art lover led.

Antinous could have just been a decoration, an expensive ring on the finger, which could be used for bragging to friends, as if a perfect work of art.

Meanwhile, Marcus felt the girl's fingers on his body. Her hand caressed, stroked his neck, his chest; she fell to her knees. Theodotus on the side step climbed on the bed and lay down next to him. He started kissing Marcus, cuddling him harder and harder. But Marcus instinctively distanced himself from them, from the boy and from Benedicta.

“We went to the thermae, master,” Benedicta said, thinking that Marcus was confused by the smell that usually comes from slaves—the stink of an unwashed body. “We poured odorous reed water on ourselves.”

“No, no!” Marcus muttered, resisting temptation.

He did not know why, why he had to fight, because his body had already surrendered, he felt it.

In his head there were images of Antinous, Psyche, Venus, whose naked sculptures were exhibited in the villa. In the afternoon, Marcus walked with the emperor past them, stopped, considered. Hadrian was silent and did not comment, sometimes looking closely at the young man. There were also busts of Cupids with The Amours. Naked and chubby boys buzzed cheerfully in copper pipes, calling the god Eros; Priapus with protruding phallus, which is a symbol of eternal fertility and the prevention of misfortune.

Meanwhile, Marcus observed that Benedicta has stopped touching him between his legs. She took out her wet arm from under his tunic and wiped it. She clearly did not know what to do next, whether to continue her caresses or, together with Theodotus, leave the master devastated by new sensations. The gap in the wall flashed with a bright reflection, disappeared, and the girl, as if receiving an inaudible order from Hadrian decided to leave the room. She called her little companion.

The lights go out, the curtain falls, the actors go away.

Marcus, leaned back, lay on the bed, feeling his face burning with hot fire and his body melting in a sweet languor. He handled himself. That's what he thought. He withstood the test prepared by Hadrian. But was it really true, did Caesar think so? Marcus didn't know.