Полная версия:

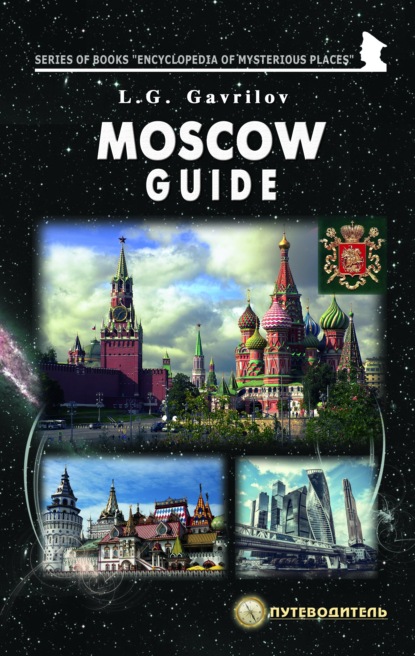

Леонид Геннадьевич Гаврилов Moscow guide

- + Увеличить шрифт

- - Уменьшить шрифт

Леонид Гаврилов

Moscow guide

© Gavrilov L.G., 2007

© Publisher Osipenko A.I., 2007

Phenomena, anomalies, ancient history and wonders of Moscow

The Byzantine icon of the Virgin and Child known as the Vladimir Icon, painted c. 1131 CE in Constantinople. Restoration following fire damage means that only the faces are original. (Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow).

Ancient settlement Kuntsevskoe

55° 43′ 11″ N

37° 26′ 26″ E

The Kuntsevo settlement is one of the oldest fortified settlements on the territory of Moscow. It is located on the western edge of the Kuntsevsky Park and occupies a high cape between two ravines. Earthen ramparts, ditches, terraces on the slopes have survived to this day. The early strata of the cultural layer (VI–V centuries BC–VII–VIII centuries AD) belong to the Dyakovo culture. During this period, there was a patriarchal settlement here. Excavations have uncovered the remains of residential and utility ground structures of a pillar structure, and a system of fortifications from the fence lines. Many finds characterize the economy and everyday life of pastoralists, hunters, early farmers and fishers. Found tools for casting non-ferrous metals, metal jewelry, products made of bone, clay, iron. In the XI–XIII centuries. Kuntsevo settlement was inhabited by Slavs-Vyatichi, engaged in arable farming and cattle breeding. Tools of labor, household and handicraft items, typical tribal ornaments were found.

In the XIII–XVI centuries. on the upper platform of the Kuntsevo settlement there was a wooden, then a stone church of the Intercession of the Mother of God, that on the Settlement. In the former's area of church cemetery, white stone carved gravestones, coins, metal crosses and icons were found here. The Moscow historian Ivan Yegorovich Zabelin, who visited the settlement in the 40s of the XX century, found a gravestone with the date: “Summer 7065, 1557 died…” Earlier slabs usually had only an ornament instead of a gravestone inscription. A settlement with a church on the territory of the Kuntsevo settlement was destroyed, probably during the Troubles in the early 17th century.

The place where the Kuntsevo settlement, since we considered it as a “pagan temple”, and several legends are associated with it. According to one of them, there was a church here, which without a trace went underground along with the cross – in one night. It depicts the Kuntsevo settlement in the painting by A.K. Savrasov “Autumn forest. Kuntsevo (Cursed Place)”, 1872. Until the twentieth century, the well-known “baba” (stone block), reminiscent of a human figure, remained a trace of pagan culture until the 20th century. Baba stood before in the middle of the peninsula in the hollow of an elm tree, then was transferred to the master's garden.

Dyakovskoe settlement

The administrative building, built in its place in the 1930s, stands on a strip foundation, so one can count on the excellent safety of the foundations and even the basements – in 1985, a completely whole crypt of Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich was already discovered. The territory of the upper Taynitsky garden is available for excavations, there may be another Dyakovskoe settlement, and the Fatyanovo burial ground, and the ancient entrance to the fortress, and the foundations of orders.

Moscow – one of the oldest European cities.

Moscow uniquely combines holy and damned disastrous and life-giving places. Famous traveler of the XIX century. Marquis Astolphe de Custine left fantastic memories of the Moscow Kremlin as a dwelling of ghosts:

“Wandering around the Kremlin, walking along Red Square, listening to the underground sounds emanating, as you dream, from the graves themselves, you believe in the supernatural.” Buried along the walls of the Moscow Kremlin are Stalin, Marshal of the Great Victory Zhukov, and many, many famous people of Russia, the Soviet Union and New Russia of the 21st century.

The history of the capital and Russia is closely intertwined with mysterious events and ominous omens, which continue to come true to this day.

Mysterious Moscow legends and legends, phenomena and unexplained phenomenaIn the distant time of the 8th century BC, at the beginning of the Iron Age, when people still had no idea who Jesus Christ was and when the scattered settlements under the leadership of Romulus first united into the city of Rome, in the place where Great Moscow now stands, the first large settlements appeared.

Probably, before that you firmly believed that only after a couple of millennia, Yuri Dolgoruky rode on a dashing horse to this land and founded a city here? So this is approximately the same truth as the fact that Columbus – before the Vikings – was the first to discover America.

On a high hill on the bank of the river, which is now called the Moskva River, in those ancient times, ancient settlers founded the first such settlement. The people that inhabited it, our contemporaries call Dyakovtsy, after the name of the village that existed here until recently, until it was demolished for new buildings. It is very difficult to say now how they called themselves, although scientists believe that it was the Mery tribe, that is, the Meryans. Unlike Ancient Rome, this people simply did not have a written language, and we can learn about it only from legends and the results of archaeological excavations.

An Etruscan bucchero vase. Second half of the 6th century BCE. (Pushkin Museum, Moscow)

The Dyakovites worshiped pagan gods, were engaged in subsistence farming and hunting for fur-bearing animals, whose fur they exchanged from the Scythians for the things they needed, defended themselves from the Mordovians and the Goths, they led the most ordinary life for the people of those times.

Although not everything is as simple as it seems at first glance. From word of mouth in legends and myths, few legends have come down to us, which indirectly or directly confirm the unusualness of these places.

Intrigued? But everything has its time, let's digress from historical data and set off ourselves in the footsteps of the ancient people. To do this, we need to take a week's supply of food, a tent, a gun to scare off bears and… leave it at home. It is better to just go out into the street, take a little metro and after a while find yourself in this place, just crossing the avenue through the underground passage.

Then you have to go what is called “vegetable gardens”. These gardens are not simple, it has cultivated the land on them since those days of the clergy. Well, what city, besides Moscow, can boast of relict vegetable gardens?

Going a little further to the bank of the Moskva River, we will see a rather large hill with steep slopes of clearly man-made nature. This place is called Devil's Town.

As I have already mentioned, the Dyakovites were pagans, and therefore among their customs there were such, by modern standards, savagery as human sacrifice. The bloody town was the very “place of execution” where these ceremonies took place. Much later, near to this dangerous place, a church was erected, which was also named rather strangely: the Temple of the Beheading of John the Baptist.

This temple is a symbol of a new state: the kingdom of Moscow. It turns out that this is not one, but “five in one” table-like temples, closely nestled against each other. The church was laid by “Ivan, the Terrible” in 1547 in memory of his wedding to the kingdom. The Dyakovsky temple served as an experimental model for the altar-temple – St. Basil's Cathedral on Red Square.

There is an opinion that Ivan the Terrible hid his famous library (liberey) just somewhere in these lands. And at the beginning of the twentieth century, some especially zealous enthusiasts looked for her here. But the relevant structures immediately thwarted their attempts. Why this happened, history is silent.

You can see the temple even today – for this we need to move about 300 meters away from the Devil's town, and it will appear in front of you in its proud solitude on the top of the cape. From the same Devil's town a beautiful panorama of Moscow opens up. The top of the town has now been excavated by archaeologists, and it fences part of it off.

The hill of the Devil's Town is surrounded by a deep ravine, now called the Voice. As the old-timers living here say, this is because birds always sing here in the summer, grasshoppers chirp and is very noisy because of the flowing stream. The stream is also very interesting, it never freezes and its temperature is always 4 degrees in any weather. Tradition tells that this stream is the footprints of the horse of Saint George the Victorious himself, who once rode here with the news of victories.

If we asked people who lived here several centuries earlier, they would have already mentioned another name for this ravine – Volosov. Because in fact, they name the ravine after the ancient deity Veles.

Snake Veles(or Volos) is an ancient, pagan god, patron of pets and wealth. The name of Veles, according to many researchers, comes from the word “hairy” – hairy. It is also possible that the word “sorcerer” just comes from the name of this god and from the custom of his priests to dress in fur “hairy” coats to imitate their deity.

The opponent of the Serpent Veles, according to ancient mythology, was the main ancient Slavic god Perun. Not only Slavic myths existed about Perun's struggle with the Serpent, or about representatives of two opposite worlds. And who knows if this ancient myth was later embodied in what Muscovites can see every day on the coat of arms of their city, where the aforementioned George the Victorious is also fighting a snake?

Volosov ravine, according to legend, and was the very abode of this not very kind pagan deity of the Dyakovites and then of the ancient Slavs. Legends also brought to us a funny fact that Veles sometimes, as they say, appeared in the flesh to residents and loved to eat eggs and drink milk. Probably, because he drank all the milk, residents had to drink something else, which made Veles appear even more often.

If you rummage in more modern archives – the 19th and early 20th centuries – you can find curious facts that our contemporaries, who did not yet know the historical essence of these places, sometimes met the so-called Bigfoot there.

Already in Soviet times, there was an amusing case when a police officer patrolling these places at night saw a huge hairy man in a ravine and was so frightened that for no apparent reason he fired the entire clip of his revolver at him. The hairy stranger did not even budge and went into the fog, or, as it is fashionable to say now, into the gloom that often happens in this ravine. It described this case in the article by A. Ryazantsev “Pioneers catching Leshego” in 1926!

An interesting case of the appearance in 1621 at the gates of the sovereign's palace of a small detachment of Tatar horsemen is also described in the “Sofia Vremennik”. They were surrounded by archers, guarding the gate, and taken prisoner. All the prisoners showed that they were the warriors of Khan Devlet-Girey, whose troops tried to capture Moscow in 1571, but were defeated and dispersed into small groups. A detachment of Cremeans, avoiding pursuit, descended into a deep ravine, shrouded in fog, in the hope of later going out into the steppe expanses. The Tatars plunged into it, it seemed, for several minutes, and emerged only 50 years later. One prisoner said that the fog was unusual, gleaming greenish, but in fear of the chase, no one paid attention to this. Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich ordered an inquiry and search, which showed that the Tatars most likely spoke the truth.

One of the interesting cases is given in the newspaper “Moskovskie Vedomosti” dated July 9, 1832, which tells about two peasants who disappeared in 1810, and appeared… in 1831. Returning at night from the village of Dyakova, the peasants of the Sadovniki village Arkhip Kuzmin and Ivan Bochkarev cut the road and go through the Volosov ravine. There was a thick fog at the bottom of the ravine. The friends, passing between two enormous boulders, suddenly fell somewhere and found themselves in a corridor, along which they went into a space filled with whitish light. Unexpectedly for themselves, they again found themselves in a ravine, but when they reached the outskirts of the village, they found themselves in a different time. There are still relatives of the disappeared in the village who have identified them, although 21 years have passed since the disappearance.

* * *Now is the time to talk about the two boulders that still lie there, and the idly staggering Muscovites and guests of our city sometimes do not even notice them. The boulders are called Devy Stone and Goose. Virgo is none other than the Finno-Ugric female underground goddess, and the Goose is a sacred bird of Finno-Ugric mythology, swimming in the underground ocean and once creating everything, throwing a slap of silt from its beak into an abyss full of dead water.

The Virgin Stone is an enormous block with many strange protruding hemispheres. It was brought here from somewhere from the north by a glacier many thousands of years ago and weighs about 5 tons. The stone helps with infertility. So, dear women, if you believe in the mystical, I advise you to touch this relic of the ancient, pre-Slavic civilization. But do not forget about an easier way to deal with the worsening demographic situation: he is now walking in the flesh next to you and begging for money for beer sold right there, in numerous tents.

Our Moscow stands on the so-called Russian platform, a fairly solid geological formation. But each platform has its own faults, and one of the largest – just passes under the Volosov ravine. Also, approximately in this place, traces of very ancient volcanic activity, dating back to the time of the dinosaurs, were found, the results of which we can observe in our time on the reliefs unusual for our city.

But back to our Dyakovites. At the beginning of the 8th century AD, 300 years before the Slavs here and the official foundation of the city of Moscow, they suddenly simply disappear. It does not reflect these three centuries in the annals or in the legends. Even archaeologists cannot yet find any traces of human activity. Therefore, for us it will remain a mystery where these ancient pramskvichs disappeared.

So you and I visited this one of the most mysterious places in our Moscow, walked in the footsteps of ancient civilizations, almost fell through in time and were cured of diseases with ancient artifacts.

I think I forgot something, right? Probably to say what kind of place this is, and what fabulous metro you can get there. Now re-read carefully the beginning of this article again. The fairy tale is always there, right next to us! This place is called very simply: Kolomenskoye!

And you probably know how to get to it, since you have done this many times. You can go, as described in the article, through the Kashirskaya metro station. Or you can do it as usual, through the Kolomenskaya metro station. Only now, when you go there again, do not stop at the very entrance, walk past the magnificent Temple of the Ascension a little further – to the southern, not very visited by tourists, part of the park, and you yourself, with your own feet, step on this ancient land, from 3 thousand years ago began the settlement of our beloved city of Moscow, which is probably not in vain called the Third Rome.

The headquarters of UNIO “Kosmopoisk” is near this area, and the data presented in this digest guide has been collected by groups of people belonging to this All-Russian Public Research Organization. We have tried to historically and popularly present such an interesting topic about our beloved city – the city of Moscow.

The book is a gift to all researchers, historians, people interested and seeking. And, of course, this guide is not the ultimate truth, and the list of phenomena is far from complete. But our desire is sincere to tell about the city, its history, secrets, riddles, clues and scientific achievements.

Moscow and about Moscow. Cosmological Moscow

It is easier to navigate along the circular metro line, where the metro station “Kurskaya” will correspond to the zero degree, the beginning of Aries. Further clockwise:

– “Taganskaya” corresponds to Taurus and the planet Venus, the color is yellow-green

– “Paveletskaya” – Gemini, planet Mercury, color yellow

– “Dobryninskaya” – Cancer, planet Moon, white

– “October” – Leo, planet Sun, red, cherry

– “Park of Culture” – Virgo, Mercury, light blue

– “Kievskaya” – Libra, Venus, aqua

– Krasnopresnenskaya – Scorpio, Pluto, blue

– “Belorusskaya” – Sagittarius, Jupiter, blue

– “Novoslobodskaya” – Capricorn, Saturn, blue

– “Prospect Mira” – Aquarius, Uranus, purple

– “Komsomolskaya” – Pisces, Neptune, green-blue

There is also an ancient eastern calendar based on a 12-year cycle. This cycle is likely associated with the period of Jupiter's revolution around the Sun – 12 years. Perhaps the largest planet in the solar system just affects earthly life?! This seems to be the case – at least for Russia. We can observe roughly the same in other countries, but with a different origin.

Calculating further into the depths of the centuries this cycle, the astrologers of India, Ancient China and Zorathustra (where these terms were named differently) agreed to consider it the beginning of the year of the Snake. Almost all known Russian troubles began in the year of the Snake or in the first six years of the 12-year cycle… 1605 (the year of the Snake): the death of Tsar Boris, the murder of his son, the accession of False Dmitry I and further a set of events characteristic of troubled times, which are famous Russian physicist Alexander Chizhevsky enlisted in the category of psychomotor epidemic: popular uprisings, riots, unrest, coups, murders, fermentation of minds, weakening of the state principle, external interventions, defensive wars, the enthronement of impostors (after 1605 there were eight of them). 862 (second year of the cycle): riots in Novgorod, accession of Rurik; the date is semi-legendary, therefore the dating is unreliable, but nevertheless… 1689: the end of the actual reign of Sophia, the accession of Peter I, the salvation of Peter I from the rebellious archers (the year of the Snake). You can also name the Pugachev riot and many other historical events…

Cycles of Russian history

Let us turn to the history of our civilization, where one of the most striking examples is the comparison of the histories of Ancient Rome (“Rome No. 1”) and the Third Rome – Moscow. In Rome, the first, as you know, Gaius Julius Caesar became the first to wear the high rank of “emperor” constantly; in the history of our country, for the first time it awarded this title to Peter I the Great. Caesar in 46 BC e. introduced the Julian calendar, in which the year began on January 1. Peter I introduced a new calendar in Russia by decree of December 15, 1699, after which the New year was also celebrated on January 1 (instead of September 1). Caesar created a headquarters in his army, introduced the position of chief of engineers; it carried a similar transformation out under Peter, the General Staff and engineering troops appeared in the Russian army. Caesar outlined his views on the conduct of hostilities in the “Notes on the Gallic War” and “Notes on the Civil War”; Peter called his similar works “The Rules of Battle” and “The Establishment in Battle”… There are many similar coincidences, since the personalities of both “first emperors” – Caesar and Peter – coincide in the main: both of them were reformers, magnificent state, political and military leaders, administrators and diplomats. So the chain of coincidences is too long to be considered pure coincidence… great state leaders, political and military leaders, administrators and diplomats. So the chain of coincidences is too long to be considered pure coincidence… great leaders, political and military leaders, administrators and diplomats. So the chain of coincidences is too long to be considered pure coincidence…

The Saratov writer Yuri Nikitin, who published the book discovered a strange coincidence in Russian history “Tsar's Fun” about the peculiarities of Russian national hunting. It turns out that in a long line of all the Russian-Soviet top leaders of the country there were only two people who were ardent opponents of shooting at animals (everyone else, including Lenin, Stalin, Brezhnev and others, was keen to hunt). These two people – Tsar Feodor Alekseevich Romanov (1661–1682) and Mikhail Sergeevich Gorbachev (b. 1931) – were separated by three centuries of history, but this is the only thing that separates them. But it unites – a lot! Each ruled for 6 years; both were under strong female influence (Agafya's wives with her aunt Tatyana Mikhailovna, and three hundred years later – Raisa Maksimovna's “family party organizer” with Margaret Thatcher); both were convinced teetotalers; both fought with privileges (boyar, and then – party); both pardoned the troublemakers and returned from exile those offended by the previous government (“Pustozersk imprisoned”, and after 3 centuries – Soviet dissidents, including A. Sakharov); both ended their terms of rule in great troubles. Relying on this almost mirror-like property, Yu. Nikitin even suggested that the next such leader would appear in our country a little less than 300 years later, in the XXIII century (KP, 1998, May 22, p. 6). By the same logic, it turns out that the previous reluctant tsars in Russia had to tragically end their reign not only in the 17th and 20th centuries, but also in the XIV, XI… and so on into the depths of the centuries. However, too little is known about the leaders of that gray-haired antiquity… both pardoned the troublemakers and personally returned from exile those offended by the previous government (“Pustozersk imprisoned”, and 3 centuries later – Soviet dissidents, including A. Sakharov); both ended their terms of rule in great troubles. Relying on this almost mirror-like property, Yu. Nikitin even suggested that the next such leader would appear in our country a little less than 300 years later, in the XXIII century (KP, 1998, May 22, p. 6). By the same logic, it turns out that the previous reluctant tsars in Russia had to tragically end their reign not only in the 17th and 20th centuries, but also in the XIV, XI… and so on into the depths of the centuries. However, too little is known about the leaders of that gray-haired antiquity… both pardoned the troublemakers and returned from exile those offended by the previous government (“Pustozersk imprisoned”, and 3 centuries later – Soviet dissidents, including A. Sakharov); both ended their terms of rule in great troubles. Relying on this almost mirror-like property, Yu. Nikitin even suggested that the next such leader would appear in our country a little less than 300 years later, in the XXIII century (KP, 1998, May 22, p. 6). By the same logic, it turns out that the previous reluctant tsars in Russia had to tragically end their reign not only in the 17th and 20th centuries, but also in the XIV, XI… and so on into the depths of the centuries. However, too little is known about the leaders of that gray-haired antiquity… Sakharov); both ended their terms of rule in great troubles. Relying on this almost mirror-like property, Yu. Nikitin even suggested that the next such leader would appear in our country a little less than 300 years later, in the XXIII century (KP, 1998, May 22, p. 6). By the same logic, it turns out that the previous reluctant tsars in Russia had to tragically end their reign not only in the 17th and 20th centuries, but also in the XIV, XI… and so on into the depths of the centuries. However, too little is known about the leaders of that gray-haired antiquity… Sakharov); both ended their terms of rule in great troubles. Relying on this almost mirror-like property, Yu. Nikitin even suggested that the next such leader would appear in our country a little less than 300 years later, in the XXIII century (KP, 1998, May 22, p. 6). By the same logic, it turns out that the previous reluctant tsars in Russia had to tragically end their reign not only in the 17th and 20th centuries, but also in the XIV, XI… and so on into the depths of the centuries. However, too little is known about the leaders of that gray-haired antiquity… that the previous reluctant tsars in Russia had to tragically end their reign not only in the 17th and 20th centuries, but also in the XIV, XI… and so on into the depths of the centuries. However, too little is known about the leaders of that gray-haired antiquity… that the previous reluctant tsars in Russia had to tragically end their reign not only in the 17th and 20th centuries, but also in the XIV, XI… and so on into the depths of the centuries. However, too little is known about the leaders of that gray-haired antiquity…