Полная версия:

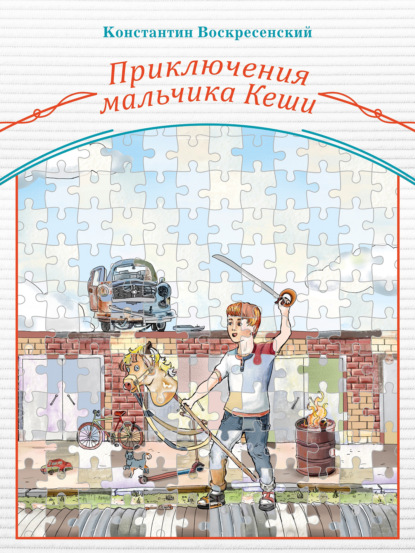

Константин Дмитриевич Воскресенский The Adventures of Kesha the Russian Boy

- + Увеличить шрифт

- - Уменьшить шрифт

Konstantin Voskresenskiy

The Adventures of Kesha the Russian Boy

Foreword

Konstantin Dmitrievich Voskresenskiy[1], whose work until now has only been released in the form of poems and «The Tale of the Coronavirus», presents to the world this book of prose based on his own life. A rather bold undertaking, given the difficult subject matter: firstly, because of the difficulty journey of self-discovery throughout adolescence, when one's personality is ever-evolving and perceives the world differently on a spiritual level. Secondly, the time frame depicted was a whirlwind, with life shifting dramatically across a huge nation; this book captures life in the immediate vicinity of the capital Moscow. And thirdly, lacking any experience writing a book, Voskresenskiy relies purely on memory.

But those now reading this book see before them the final product; the difficulties have been ironed out, from key moments to tiny details. In this book, over thirty years of the central character's life and the country where he lives, works and indulges in literary creativity, emerge as a whole. It is a living, breathing organism with all its vital organs and functional features.

At the beginning of the story, we find the central character still a child, who like all children, is not too aware of himself in this world. He is growing, developing, and absorbing the good with the bad. He goes through periods familiar to anyone with experience of bringing up preschool and school-age children and how their minds work. Here we find inquisitiveness, a thirst for knowledge, bouts of negativity, first-time experiences and first disappointments.

In adolescence, the central character undergoes typical teenage «restructuring». He breaks away from the emerging set of values, sometimes in a very painful and frightening manner. His teenage years brought the need to «find himself», whereby he decided which path he would take on into the future.

The author depicts each of these stages with soul, fascination and directness, while maintaining a masterful hand. His creative truth does not contradict this depiction of his life, as can often happen with novice authors and other modern artists. Konstantin Voskresenskiy gave us a piece of work that, when reading, involuntarily takes us back to Russian classics about childhood, such as Nikolai Garin-Mikhailovsky's «Tyoma's Childhood» and Maxim Gorky's «My Childhood».

I hope that Konstantin Voskresenskiy's future as a writer will grow in such a way that this, what I deem to be, successful experience will only be further underlined by subsequent successes along his literary path.

Sergey Smetanin[2], Member of the Union of Russian WritersPreface

Welcome, everyone. I am glad to present to you my autobiography. Both to those who know me personally, as well as the curious minds, thinking, searching and reading this book. Every person is a universe, a mystery and a real miracle. I'm sure each of you has something to say about yourselves, as well as recall and recant from your lives. But with this book I want to share my universe, my reflections, and talk about my adventures. This is not a memoir. This is about the very extraordinary life of an ordinary person from an ordinary family. And, importantly, it includes moments that have occurred in very few people's lives, especially in such quantities as in mine, or in the same order.

It is worth noting that this book does not cover the topic of love. On one hand, I could have written a separate edition of seven volumes on the subject. On the other hand, my story wasn't particularly out of the ordinary, so why tell the tale? Moreover, I covered this topic, albeit without commentary, in my first book: a collection of lyrical poems «In Your Name[3]».

All of the names, dates and events recounted in this book are real and are not fictional.

Chapter 1. 1985. The Beginning

1985. Kesha

Let's start with the boy's name in the title of the book.

You must agree that naming a child is a fascinating but difficult task. Many parents will confirm this. In our day, my wife and I also faced this task. We cheated a little, naming our child after the saint of the month she was born. This practice in the Eastern Orthodox Church and Eastern Catholic Churches that follow the Byzantine Rite.

My mum decided to call me Innokenty, or Innocentius in its Latin form. I lived with that name for almost two weeks. Later it turned out that not everyone liked it, which she discovered when my aunt Nadia came to the baby shower. At the time, she was still at primary school. When they told her what I was called, she said, «Oh, I know, he should be called Kesha! I watched a cartoon yesterday about a parrot called Kesha…» My granny Marina lost her patience and emphatically stated that no grandson of hers would be called Innocentius. The boys would tease him at school!

But if this was no longer his name, then what was? They decided to write three names write on three pieces of paper – Ilya, Roman and Konstantin – and mum picked them out of a hat. Lo and behold, I became Konstantin.

To be honest, I would have been satisfied with the first name, but the one I ended up with is much more normal…

1986. My father's death

But changing names is just for starters. More significant events were just around the corner. When I was one year and five days old, I found myself without a father. My dad, Dmitriy Voskresenskiy, was killed while serving in the military at the (tender) age of 19.

You may not be familiar with how they recruited for the Soviet Army. Long story short, the USSR conscripted young men from the age of 18. Back then, they had to serve for two years. These days, lads tend to serve one year. This can be for many reasons, for example, men are excluded on medical grounds or defer their service because of academic or familial commitments.

When I was born, the Soviet military system, as strange and erratic as it was, gave my father six months leave to help care for me as a new-born. After that, they sent him 3,500 miles away to the remote Amur region on the border with China.

After five months of service, there was an attack by «unknown persons» on a military unit near the city of Blagoveshchensk, where my father was serving with his comrades. For his «main course» my father was served five bullet wounds, and gas poisoning came «for dessert». No, don't try and look up this news from 20th August 1986. The death certificate clearly states «Hemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome» because «Killed by bullets and poisoning» is an unproven hypothesis in the eyes of the state. In fact, it's not even in any archives. This has been contested many times to Russian Defence Minister Sergey Shoygu, until in 2016, the Military Prosecutor said: «Would you care to explain who told you about this?» If you're not working within the military system or the state, there's no point in trying to find out what really happened.

Apparently, it doesn't matter how he died: in any case, Cargo 200[4] means Cargo-200. Only my grandad was there to identify my father's body. But, oddly enough, it wasn't my father's father, but my mum's father, Nikolay Timanov. At one point he started to tell me about it, but then he stopped immediately and pressed pause on this conversation. He never got around to telling me before he passed away. Nonetheless, our family gathered much of what he probably wanted to say, even without him saying it out loud. After all, we had another source; my babushka's[5] friend worked at the morgue the year father died, and she let a lot of information slip. Nowadays you can write to Putin (I've written, but more on that later). But back then, times were different. No one in our family ever tried to find anything out while the trail was still hot. I can't say I blame them, but I think they should have at least tried. Of course, it wouldn't have brought their husband, your son or brother back, but they had a little son, grandson and nephew to think of…

It is not difficult to assume that the death of my father radically changed both my fate and that of my mother.

1988. A New Dad

My mum was a beautiful young woman. Even with a baby in her arms she could stop a man in his tracks. After just one summer of being a family of two, with just 24 years between us, a new dad appeared. I don't remember this, since I was only three years old. I always called him «dad». We are still friends and get on well; he never said a word in anger or laid a finger on me. Actually, he preferred not to interfere, but just help out financially. I can't say it was the most successful strategy, but I'm eternally grateful to him. He gave me space to grow up by myself, without trying to forge me in his own image. I didn't have to match up to his standards. Some forethought and a light-touch are valuable qualities…

Chapter 2. 1988. First Shocks

1988. Went for a bite to eat

In the summer of 1988, a funny little thing happened in Yevpatoria, Crimea. Well, it wasn't that funny… I got lost. My mother and aunt Ira left me on the beach while they went for a swim. I'm sure they asked some other responsible-looking lady on the beach in a wide-brimmed hat to watch over me. But I'm also sure that she barely took a bit of notice at what I was up to, she was more interested in the sun, the sea, and the beach. When they came back from their swim, I wasn't there. They called out, shouting for me… Nothing. They ran all over the place and spotted me walking along the tram tracks chewing on a tasty bun.

«Where did you get this from? Where were you?» asked mum.

«I went for a bite to eat…» I said.

Oh yes… a small little man, but a hearty eater. Thank God that ended well enough that it remained funny and relatively short.

1988. Fire

Another unpleasant story happened the very same summer. Perhaps even more serious: there was a fire. I remember clearly how my grandmother's room in her flat on the second floor of a five-storey brick building was on fire. Thankfully, Grandma and everybody else were fine. Cars, fumes, people rushing around – that's what impressed me the most. This was the first time I'd seen such a commotion and crowd of onlookers. Of course, I didn't really understand what was going on, but the general anxiety made a real impression on me. Since then, every time I see a fire, I literally go numb and mentally fall back to this episode.

1988. Promising to cut my tongue off

So, summer ended, and kindergarten began, leaving a deep incurable wound in my soul. For me, girls were always the epitome of divine beauty. I don't know who taught me that or when, but it's what I believed. So, what stood out most to me in my kindergarten years? A scruffy blonde girl in a black-and-white plaid dress, smeared with porridge. A real mess like I'd never seen before. Good God, this harsh reality broke my little, naïve, childish world. I started to refuse to go to kindergarten, kicking up a huge fuss, for fear that I would have to see her again.

There was one girl I liked. I remember neither her appearance nor her name, but it doesn't matter. It so happened that our little beds were next to each other during nap time, so I started a conversation with her. «Hello,» I would say, «How are you?» As if I was greeting a stranger. Of course, the kindergarten teacher was quickly on me, promising to cut my tongue off for speaking during nap time… It sounded so threatening and so convincing that you would believe it yourself even now. Ever since that day I use my words carefully, often choosing to keep quiet. Because who knows what might happen…

1989. Forgetfulness

The challenges to my young psyche did not end there.

One day, nobody picked me up from kindergarten. I sat there late into the night until a relative who worked there picked me up. What was I thinking about? Nothing. I just sat there, still as a statue, watching out the window. Outside, everything was quiet, snowflakes were falling and covering the oaks and pathways. It grew dark.

A similar thing occurred during the summer school holidays. I was out all day, and in the evening, nobody let me back inside the house. It wasn't a nasty joke or out of unkindness, just, there was nobody home. And I didn't have a key. At about 9 o'clock in the evening, my neighbour, Vera's mother from flat number 48, took me inside. We all watched a children's TV show together, had dinner and went to bed. I was given a place to sleep in with Vera's brother.

In both cases, many years later, I heard very convincing stories about what difficulties had befallen my parents that meant they couldn't come and pick me up or let me inside. But the harsh truth is simple: both my mother and my stepfather were, at some point in their lives, drunks. I don't exactly have evidence, but I'm sure that while these things were happening to me, they were at my stepfather's place in a nearby town or at someone else's flat. I'm not blaming anyone, but, as it I often say in my anecdotes: «it left its mark…».

1990. Stutterer

I started to stutter at the age of about five. It all happened very fast…

At that time, I was on holiday, staying with my late father's grandmother in Klimovsk, about two hours outside of central Moscow. I was taking a walk outside. At some point, my rumbly belly told me to go home, and instead of walking all the way around the fence to get back, I decided to take a shortcut by running quickly under other people's windows. I was fast, so fast that I ran through the entrance to the door and almost went headfirst into one of the nice old ladies from our apartment block. A loud cry echoed through the entranceway…

As it turned out, the old lady was not so nice, and I was a pest worse than the Colorado potato beetle… That bit I just ran through was actually her garden! I don't really remember what happened after that, but I was terrified. Like, off the charts terrified.

Another new page in my life had begun. I switched, of my own accord (or maybe adults encouraged me?) from communicating through speech to the written word. Throughout primary school, I had little contact with anyone and always found it difficult to talk to our teacher, Ms. Tatiana Lazarevna, in class.

A long time has passed since then. At work, I often have to speak a lot and perform to audiences of 10 to 50 to 100 people. And in rare moments of intense nervousness, it can be very difficult for me to start talking. I have to take a little pause, a deep breath of up to three seconds and… slo-w-ly pronounce the first word on an exhale with a little riff. Once the first word is out, the second word follows quite nicely. And before I know it, my mini moment of embarrassment is over.

Chapter 3. 1990. First Adventures

1990. A one-way trip up the tree

If my first shocks came from the outside world, about which there was little that I could do, then my first adventures were the fruit of my more or less conscious decisions. My growing inner world was catching up with the outside world, bringing about various activities.

One day my curiosity led me to a tree branch from which I couldn't climb down by myself. And I didn't even try to, which was probably for the best. There were a few things to note here. Firstly, this tree was not far away, only in the yard by the next house over from us. Secondly, the boys there said I should do it. Thirdly, although I knew these boys, they were hardly close friends, but they were older. And fourthly, I had been warned that while it might be easy to climb up, it's hard to get down. Then again, I'd also been taught that «you can do anything if you put your mind to it».

It wasn't that high up, just two or three metres from the ground. But this height stirred up interesting sensations in me, as I think most men will understand. It opened up a wonderful view in front of me. That said, I already lived on the sixth floor. What views could I possibly see from a tree that I couldn't I see from 16 metres high…?

So, up we climbed, sat for a while, then it was time to get down. After taking a little time on trying to get down, I realised that I couldn't do it by myself, and my friends had already gone. Thanks lads, older boys from the yard over, who I barely knew.

So, there I sat, waiting for something, not sure what. It was lunchtime, so I was beginning to get hungry… Should I shout for help? Nope. First of all, that would be too embarrassing. Second of all, I was a man, not an old lady at a market stall. I can't say that I was sitting there very long, I got lucky. My friends ran by and asked me where my piece of cheese was. I didn't get it at first, but then I realised they were joking, as if I were the crow from the fable «The Crow and the Fox» that we'd learnt at school. What they were saying was: I should ask for some help. It was lunchtime, so I asked them to call my mother. She soon came running out, bringing a big strong man with her who plucked me out of the tree just as easily as I'd gotten up there in the first place. When we got in, she didn't tell me off, she wasn't cross. I'd already learnt my lesson, no need to shout about it.

1990. As if falling from the second floor

That feeling I got from being up high in the tree was bugging me, I wanted more. Or maybe I'd just forgotten the previous adventure too quickly, as is often the case with children. This time I tried a ladder. Not like a firefighter's ladder, and not just a staircase, an ordinary ladder. There was one still in my dad's yard out in L'vovskaya, outside of Moscow.

Even now, despite modern health amp; safety regulations, playgrounds are full of dangers. The playground I played in as a kid was made of solid metal: harsh, solid, unyielding. Like life itself. And so, after having mastered what we basically considered Everest, I decided to climb this ladder, without any training or equipment. I almost got to the top before, just like in the movies, I suddenly slipped on the penultimate step and came crashing down backwards. I fell with a thud, got up, brushed myself off, and went home to eat pancakes. And that was the end of that.

Now, that's quite scary, thinking back. Falling from a height equivalent to the second floor of a block of flat is no joke. But back then? Ah, piece of cake. No one saw, it didn't hurt, all was well.

1990. Fall off the carousel

After that I'd realised that vertical ascents were not my forte and decided to experiment with horizontal movements. And it didn't take me long to sustain an injury: I got five holes in my bum… Allow me to explain.

It turns out that the harsh reality is this: if you sit and spin on a kids' roundabout, not facing the way you're going, then when you come to a sharp halt with your feet, your body is probably going to slide right off the seat and hit the ground like a sack of potatoes. Obvious? Not to every five-year-old. And landing on a board of nails at the bottom, well, that's an annoying detail.

I sent a terrible shrill cry echoing around the playground. Thank god I was only five with the vocabulary to suit, nowadays I would have screeched every swear word under the sun. My mum heard me straight away and came running. She'd been standing just around the corner the whole time…

She took me home, treated my wounds, comforted me, and didn't even tell me off. Mums are just great, aren't they?

1993. Left arm

Having suffered such a public and even slightly shameful fiasco in my horizontal adventure, I decided to return to try vertical ones again. In any case, I hadn't gotten that hurt. There were only a few things available to climb, so again, I tried a tree. But this time I had everything under control. The first branch, the second branch, the third… Oops… And we're back down in the dirt again, as if the floor was giving this brave little lad a pat on the back for trying.

As it turned out, I didn't have a parachute, nor a rescue catapult on me. Fail to prepare, prepare to fail: I dislocated my left arm. Nothing too serious. I mean it was tolerable, and no one was going to find out anyway… The next day, like a good little Soviet boy, I would be heading to a pioneer summer camp. But not just any camp, the summer camp in Crimea named in honour of Oleg Koshevoy[6]. What if they wouldn't let me go because of my arm?! I was hardly going to let that happen.

1993. Hospitals

I lay in hospital for the first time with pneumonia when was just one, but I certainly do not remember it. I only know about it from the stories grown-ups told me. But when doctors removed my adenoids at the age of seven – oh, yes, I won't be forgetting that one in a hurry.

In a large brightly lit room, there was a large table on which lay various white-enamel medical utensils and shiny tools. The soft summer sun shone through large clean windows, pleasantly and mysteriously illuminating the people dressed all in white, like angels. These angels circled around me, affectionately throwing a large white sheet over my chest and politely asking me to say «Ahhhhh». A stormy stream of warm scarlet blood spilled out of my mouth onto the white sheet and dripped down onto the floor.

And now I think: could they not have given me a heads up about that? I understand that doctors don't usually warn their patients to avoid panic, but my God, this scarred me for life…

1994. Bitten by a shepherd

Let's talk about my left arm again. Of course, it had already managed to heal after the last fall, but not for long. My power of deduction says it must have been 1994, but that's not that important.

It was summer, July. We went to visit my aunt Galya, who was widowed after my uncle, my mum's brother, Andrey Timanov, passed away. It was hot and we took the shortest path through the garden (a plot of 30 acres or so). Eventually, we saw our aunt entering the house. With joy, I rushed towards her. But as if to catch some kind of lawless maniac, a German shepherd grabbed my left arm by the teeth. He managed to bite right through the palm of my hand. Sticking out of the wound was some thick yellow thread – not from my t-shirt, oh no. It was a piece of muscle, or something.

Weirdly, the dog was usually well-behaved and had never harmed a child before. Perhaps he had just woken up or my movements were too loud and erratic. Well, either way, something wasn't quite right…

It was quite the family embarrassment. What do we do now? The next day we went to the hospital and got my hand treated. I was prescribed 40 injections to the stomach, which seemed over-the-top and downright troublesome to me and my mum, since the dog was our family's dog, it wasn't stray or rabid. So, we went to get an official document to certify that he was indeed rabies free, and as a result, I got off with only 2–3 injections to the stomach. It wasn't very pleasant, but I'd had worse…

1995. Sledging

I decided to give my arm a break and turn my attention to other body parts. This isn't going to end well. During the school holidays, I went out, without permission, to go sledding on the hill. Well, it wasn't really a hill, it was more like sneaking behind the local townhall and down towards the stream. The slope was fairly steep there. What we didn't know was that it was actually a pedestrian area, we barely even noticed the older ladies walking around with their shopping bags, blocking the runway…

At the time, I was ten years old and therefore far too old to be sledging the way I was used to (i.e., on my bum). I wasn't no toddler anymore. If I wanted to avoid being laughed at, I'd have to try balancing on the side of the sledge will going down the hill or going headfirst.

I decided to do it the way the others were – on my belly, headfirst. And I did so almost all day, until I had an unfortunate accident. Blockage on the runway, sledge jam, and a huge blow to the face as I smashed into the sledge in front of me. I walked home with my tail between my legs…