Полная версия

Полная версия- Рейтинг Литрес:5

Полная версия:

Гарриет Бичер-Стоу Uncle Tom's Cabin, Young Folks' Edition

- + Увеличить шрифт

- - Уменьшить шрифт

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Uncle Tom's Cabin, Young Folks' Edition

CHAPTER I

UNCLE TOM AND LITTLE HARRY ARE SOLD

VERY many years ago, instead of having servants to wait upon them and work for them, people used to have slaves. These slaves were paid no wages. Their masters gave them only food and clothes in return for their work.

When any one wanted servants he went to market to buy them, just as nowadays we buy horses and cows, or even tables and chairs.

If the poor slaves were bought by kind people they would be quite happy. Then they would work willingly for their masters and mistresses, and even love them. But very often cruel people bought slaves. These cruel people used to beat them and be unkind to them in many other ways.

It was very wicked to buy and sell human beings as if they were cattle. Yet Christian people did it, and many who were good and kind otherwise thought there was no wrong in being cruel to their poor slaves. 'They are only black people,' they said to themselves. 'Black people do not feel things as we do.' That was not kind, as black people suffer pain just in the same way as white people do.

One of the saddest things for the poor slaves was that they could never long be a happy family all together—father, mother, and little brothers and sisters—because at any time the master might sell the father or the mother or one of the children to some one else. When this happened those who were left behind were very sad indeed—more sad than if their dear one had died.

Uncle Tom was a slave. He was a very faithful and honest servant, and his master, Mr. Shelby, was kind to him. Uncle Tom's wife was called Aunt Chloe. She was Mr. Shelby's head cook, and a very good one too, she was. Nobody in all the country round could make such delicious pies and cakes as Aunt Chloe.

Uncle Tom and Aunt Chloe lived together in a pretty little cottage built of wood, quite close to Mr. Shelby's big house.

The little cottage was covered with climbing roses, and the garden was full of beautiful bright flowers and lovely fruit trees.

Uncle Tom and Aunt Chloe lived happily for many years in their little cottage, or cabin, as it was called. All day Uncle Tom used to work in the fields, while Aunt Chloe was busy in the kitchen at Mr. Shelby's house. When evening came they both went home to their cottage and their children, and were merry together.

Mr. Shelby was a good man, and kind to his slaves, but he was not very careful of his money. When he had spent all he had, he did not know what to do to get more. At last he borrowed money from a man called Haley, hoping to be able to pay it back again some day.

But that day never came. Haley grew impatient, and said, 'If you don't pay what you owe me, I will take your house and lands, and sell them to pay myself back all the money I have lent to you.'

So Mr. Shelby sold everything he could spare and gathered money together in every way he could think of, but still there was not enough.

Then Haley said, 'Give me that slave of yours called Tom—he is worth a lot of money.'

But Mr. Shelby knew that Haley was not a nice man. He knew he did not want Tom for a servant, but only wanted to sell him again, to make more money. So Mr. Shelby said, 'No, I can't do that. I never mean to sell any of my slaves, least of all Tom. He has been with me since he was a little boy.'

'Oh very well,' said Haley, 'I shall sell your house and lands, as I said I should.'

Mr. Shelby could not bear to think of that, so he agreed to let Haley have Tom. He made him promise, however, not to sell Tom again except to a kind master.

'Very well,' said Haley, 'but Tom isn't enough. I must have another slave.'

Just at this moment a little boy came dancing into the room where Mr. Shelby and Haley were talking.

He was a pretty, merry little fellow, the son of a slave called Eliza, who was Mrs. Shelby's maid.

'There now,' said Haley, 'give me that little chap, as well as Tom, and we will say no more about the money you owe me.'

'I can't,' said Mr. Shelby. 'My wife is very fond of Eliza, and would never hear of having Harry sold.'

'Oh, very well,' said Haley once more, 'I must just sell your house.'

So again Mr. Shelby gave in, and Haley went away with the promise that next morning Uncle Tom and little Harry should be given to him, to be his slaves.

CHAPTER II

ELIZA RUNS AWAY WITH LITTLE HARRY

Mr. Shelby was very unhappy because of what he had done. He knew his wife would be very unhappy too, and he did not know how to tell her.

He had to do it that night, however, before she went to bed.

Mrs. Shelby could hardly believe it. 'Oh, you do not mean this,' she said. 'You must not sell our good Tom and dear little Harry. Do anything rather than that. It is a wicked, wicked thing to do.

'There is nothing else I can do,' said Mr. Shelby. 'I have sold everything I can think of, and at any rate now that Haley has set his heart on having Tom and Harry, he would not take anything or anybody instead.'

Mrs. Shelby cried very much about it, but at last, though she was very, very unhappy she fell asleep.

But some one whom Mr. and Mrs. Shelby never thought of was listening to this talk.

Eliza was sitting in the next room. The door was not quite closed, so she could not help hearing what was said. As she listened she grew pale and cold and a terrible look of pain came into her face.

Eliza had had three dear little children, but two of them had died when they were tiny babies. She loved and cared for Harry all the more because she had lost the others. Now he was to be taken from her and sold to cruel men, and she would never see him again. She felt she could not bear it.

Eliza's husband was called George, and was a slave too. He did not belong to Mr. Shelby, but to another man, who had a farm quite near. George and Eliza could not live together as a husband and wife generally do. Indeed, they hardly ever saw each other. George's master was a cruel man, and would not let him come to see his wife. He was so cruel, and beat George so dreadfully, that the poor slave made up his mind to run away. He had come that very day to tell Eliza what he meant to do.

As soon as Mr. and Mrs. Shelby stopped talking, Eliza crept away to her own room, where little Harry was sleeping. There he lay with his pretty curls around his face. His rosy mouth was half open, his fat little hands thrown out over the bed-clothes, and a smile like a sunbeam upon his face.

'My baby, my sweet-one,' said Eliza, 'they have sold you. But mother will save you yet!'

She did not cry. She was too sad and sorrowful for that. Taking a piece of paper and a pencil, she wrote quickly.

'Oh, missis! dear missis! don't think me ungrateful—don't think hard of me, anyway! I heard all you and master said to-night. I am going to try to save my boy—you will not blame me I God bless and reward you for all your kindness!'

Eliza was going to run away.

She gathered a few of Harry's clothes into a bundle, put on her hat and jacket, and went to wake him.

Poor Harry was rather frightened at being waked in the middle of the night, and at seeing his mother bending over him, with her hat and jacket on.

'What is the matter, mother?' he said beginning to cry.

'Hush,' she said, 'Harry mustn't cry or speak aloud, or they will hear us. A wicked man was coming to take little Harry away from his mother, and carry him 'way off in the dark. But mother won't let him. She's going to put on her little boy's cap and coat, and run off with him, so the ugly man can't catch him.'

Harry stopped crying at once, and was good and quiet as a little mouse, while his mother dressed him. When he was ready, she lifted him in her arms, and crept softly out of the house.

It was a beautiful, clear, starlight night, but very cold, for it was winter-time. Eliza ran quickly to Uncle Tom's cottage, and tapped on the window.

Aunt Chloe was not asleep, so she jumped up at once, and opened the door. She was very much astonished to see Eliza standing there with Harry in her arms. Uncle Tom followed her to the door, and was very much astonished too.

'I'm running away, Uncle Tom and Aunt Chloe—carrying off my child,' said Eliza. 'Master sold him.'

'Sold him?' they both echoed, lifting up their hands in dismay.

'Yes, sold him,' said Eliza. 'I heard master tell missis that he had sold my Harry, and you, Uncle Tom. The man is coming to take you away to-morrow.'

At first Tom could hardly believe what he heard. Then he sank down, and buried his face in his hands.

'The good Lord have pity on us!' said Aunt Chloe. 'What has Tom done that master should sell him?'

'He hasn't done anything—it isn't for that. Master don't want to sell; but he owes this man money. If he doesn't pay him it will end in his having to sell the house and all the slaves. Master said he was sorry. But missis she talked like an angel. I'm a wicked girl to leave her so, but I can't help it. It must be right; but if it an't right, the good Lord will forgive me, for I can't help doing it.

'Tom,' said Aunt Chloe, 'why don't you go too? There's time.'

Tom slowly raised his head and looked sorrowfully at her.

'No, no,' he said. 'Let Eliza go. It is right that she should try to save her boy. Mas'r has always trusted me, and I can't leave him like that. It is better for me to go alone than for the whole place to be sold. Mas'r isn't to blame, Chloe. He will take care of you and the poor—'

Tom could say no more. Big man though he was, he burst into tears, at the thought of leaving his wife and dear little children, never to see them any more.

'Aunt Chloe,' said Eliza, in a minute or two, 'I must go. I saw my husband to-day. He told me he meant to run away soon, because his master is so cruel to him. Try to send him a message from me. Tell him I have run away to save our boy. Tell him to come after me if he can. Good-bye, good-bye. God bless you!'

Then Eliza went out again into the dark night with her little boy in her arms, and Aunt Chloe shut the door softly behind her.

CHAPTER III

THE MORNING AFTER

Next morning, when it was discovered that Eliza had run away with her little boy, there was great excitement and confusion all over the house.

Mrs. Shelby was very glad. 'Thank God!' she said. 'I hope Eliza will get right away. I could not bear to think of Harry being sold to that cruel man.'

Mr. Shelby was angry. 'Haley knew I didn't want to sell the child,' he said. 'He will blame me for this.'

One person only was quite silent, and that was Aunt Chloe. She went on, making the breakfast as if she heard and saw nothing of the excitement round her.

All the little black boys belonging to the house thought it was fine fun. Very soon, about a dozen young imps were roosting, like so many crows, on the railings, waiting for Haley to come. They wanted to see how angry he would be, when he heard the news.

And he was dreadfully angry. The little nigger boys thought it was grand. They shouted and laughed and made faces at him to their hearts' content.

At last Haley became so angry, that Mr. Shelby offered to give him two men to help him to find Eliza.

But these two men, Sam and Andy, knew quite well that Mrs. Shelby did not want Eliza to be caught, so they put off as much time as they could.

They let loose their horses and Haley's too. Then they frightened and chased them, till they raced like mad things all over the great lawns which surrounded the house.

Whenever it seemed likely that a horse would be caught, Sam ran up, waving his hat and shouting wildly, 'Now for it! Cotch him! Cotch him!' This frightened the horses so much that they galloped off faster than before.

Haley rushed up and down, shouting and using dreadful, naughty words, and stamping with rage all the time.

At last, about twelve o'clock, Sam came riding up with Haley's horse. 'He's cotched,' he said, seemingly very proud of himself. 'I cotched him!'

Of course, now it was too late to start before dinner. Besides, the horses were so tired with all their running about, that they had to have a rest.

When at last they did start, Sam led them by a wrong road. So the sun was almost setting before they arrived at the village where Haley hoped to find Eliza.

CHAPTER IV

THE CHASE

When Eliza left Uncle Tom's cabin, she felt very sad and lonely. She knew she was leaving all the friends she had ever had behind her.

At first Harry was frightened. Soon he grew sleepy. 'Mother, I don't need to keep awake, do I?' he said.

'No, my darling, sleep, if you want to.'

'But, mother, if I do get asleep, you won't let the bad man take me?'

'No!'

'You're sure, an't you, mother?'

'Yes, sure.'

Harry dropped his little weary head upon her shoulder, and was soon fast asleep.

Eliza walked on and on, never resting, all through the night. When the sun rose, she was many miles away from her old home. Still she walked on, only stopping, in the middle of the day, to buy a little dinner for herself and Harry at a farm-house.

At last, when it was nearly dark, she arrived at a village, on the banks of the river Ohio. If she could only get across that river, Eliza felt she would be safe.

She went to a little inn on the bank, where a kind-looking woman was busy cooking supper.

'Is there a boat that takes people across the river now?' she asked.

'No, indeed,' replied the woman. 'The boats has stopped running. It isn't safe, there be too many blocks of ice floating about.'

Eliza looked so sad and disappointed when she heard this, that the good woman was sorry for her. Harry too was so tired, that he began to cry.

'Here, take him into this room,' said the woman, opening the door into a small bed-room.

Eliza laid her tired little boy upon the bed, and he soon fell fast asleep. But for her there was no rest. She stood at the window, watching the river with its great floating blocks of ice, wondering how she could cross it.

As she stood there she heard a shout. Looking up she saw Sam. She drew back just in time, for Haley and Andy were riding only a yard or two behind him.

It was a dreadful moment for Eliza. Her room opened by a side door to the river. She seized her child and sprang down the steps towards it.

Haley caught sight of her as she disappeared down the bank. Throwing himself from his horse, and calling loudly to Sam and Andy, he was after her in a moment.

In that terrible moment her feet scarcely seemed to touch the ground. The next, she was at the water's edge.

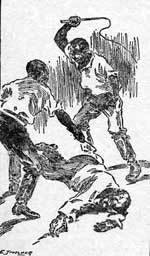

On they came behind her. With one wild cry and flying leap, she jumped right over the water by the shore, on to the raft of ice beyond. It was a desperate leap. Haley, Sam, and Andy cried out, and lifted up their hands in astonishment.

The great piece of ice pitched and creaked as her weight came upon it. But she stayed there not a moment. With wild cries she leaped to another and still another—stumbling—leaping—slipping—springing up again!

Her shoes were gone, her stockings cut from her feet by the sharp edges of the ice. Blood marked every step. But she knew nothing, felt nothing, till dimly, as in a dream, she saw the Ohio side, and a man helping her up the bank.

'Yer a brave gal, now, whoever ye are!' said the man.

'Oh, save me—do save me—do hide me,' she cried.

'Why, what's the matter?' asked the man.

'My child! this boy—mas'r sold him. There's his new mas'r,' she said, pointing to the other shore. 'Oh, save me.'

'Yer a right brave gal,' said the man. 'Go there,' pointing to a big white house close by. 'They are kind folks; they'll help you.'

'Oh, thank you, thank you,' said Eliza, as she walked quickly away. The man stood and looked after her wonderingly.

On the other side of the river Haley was standing perfectly amazed at the scene. When Eliza disappeared over the bank he turned and looked at Sam and Andy, with terrible anger in his eyes.

But Sam and Andy were glad, oh, so glad, that Eliza had escaped. They were so glad that they laughed till the tears rolled down their cheeks.

'I'll make ye laugh,' said Haley, laying about their heads with his riding whip.

They ducked their heads, ran shouting up the bank, and were on their horses before he could reach them.

'Good evening, mas'r,' said Sam. 'I berry much 'spect missis be anxious 'bout us. Mas'r Haley won't want us no longer.' Then off they went as fast as their horses could gallop.

It was late at night before they reached home again, but Mrs. Shelby was waiting for them. As soon as she heard the horses galloping up she ran out to the balcony.

'Is that you, Sam?' she called. 'Where are they?'

'Mas'r Haley's a-restin' at the tavern. He's drefful fatigued, missis.'

'And Eliza, Sam?'

'Come up here, Sam,' called Mr. Shelby, who had followed his wife, 'and tell your mistress what she wants to know.'

So Sam went up and told the wonderful story of how Eliza had crossed the river on the floating ice. Mr. and Mrs. Shelby found it hard to believe that such a thing was possible.

Mrs. Shelby was very, very glad that Eliza had escaped. She told Aunt Chloe to give Sam and Andy a specially good supper. Then they went to bed quite pleased with their day's work.

CHAPTER V

ELIZA FINDS A REFUGE

A lady and gentleman were sitting talking happily together in the drawing-room of the white house to which Eliza had gone. Suddenly their old black man-of-all-work put his head in at the door and said, 'Will missis come into the kitchen?'

The lady went. Presently she called to her husband, 'I do wish you would come here a moment.'

He rose and went into the kitchen.

There lay Eliza on two kitchen chairs. Her poor feet were all cut and bleeding, and she had fainted quite away. The master of the house drew his breath short, and stood silent.

His wife and the cook were trying to bring Eliza round. The old man had Harry on his knee, and was busy pulling off his shoes and stockings, to warm the little cold feet.

'Poor creature,' said the lady.

Suddenly Eliza opened her eyes. A dreadful look of pain came into her face. She sprang up saying, 'Oh, my Harry, have they got him?'

As soon as he heard her voice, Harry jumped from the old man's knee, and running to her side, put up his arms.

'Oh, he's here! he's here,' she said, kissing him. 'Oh, ma'am,' she went, on turning wildly to the lady of the house, 'do protect us, don't let them get him.'

'Nobody shall hurt you here, poor woman,' said the lady. 'You are safe; don't be afraid.'

'God bless you,' said Eliza, covering her face and sobbing, while Harry, seeing her crying, tried to get into her lap to comfort her.

'You needn't be afraid of anything; we are friends here, poor woman. Tell me where you come from and what you want,' said the lady.

'I came from the other side of the river,' said Eliza.

'When?' said the gentleman, very much astonished.

'To-night.'

'How did you come?'

'I crossed on the ice.'

'Crossed on the ice!' exclaimed every one.

'Yes,' said Eliza slowly, 'I did. God helped me, and I crossed on the ice. They were close behind me—right behind, and there was no other way.'

'Law, missis,' said the old servant, 'the ice is all in broken up blocks, a-swinging up and down in the water.'

'I know it is. I know it,' said Eliza wildly. 'But I did it. I would'nt have thought I could—I didn't think I could get over, but I didn't care. I could but die if I didn't. And God helped me.'

'Were you a slave?' said the gentleman.

'Yes, sir.'

'Was your master unkind to you?'

'No, sir.'

'Was your mistress unkind to you?'

'No, sir—no. My mistress was always good to me.'

'What could make you leave a good home, then, and run away, and go through such danger?'

'They wanted to take my boy away from me—to sell him—to sell him down south, ma'am. To go all alone—a baby that had never been away from his mother in his life. I couldn't bear it. I took him, and ran away in the night. They chased me, they were coming down close behind me, and I heard 'em. I jumped right on to the ice. How I got across I don't know. The first I knew, a man was helping me up the bank.'

It was such a sad story, that the tears came into the eyes of everyone who heard her tell it.

'Where do you mean to go to, poor woman?' asked the lady.

'To Canada, if I only knew where that was. Is it very far off, is Canada'? said Eliza, looking up in a simple, trusting way, to the kind lady's face.

'Poor woman,' said she again.

'Is it a great way off?' asked Eliza.

'Yes,' said the lady of the house sadly, 'it is far away. But we will try to help you to get there.' Eliza wanted to go to Canada, because it belonged to the British. They did not allow any one to be made a slave there. George, too, was going to try to reach Canada.

'Wife,' said the gentleman, when they had gone back again into their own sitting-room, 'we must get that poor woman away to-night. She is not safe here. I know some good people, far in the country, who will take care of her.'

So this kind gentleman got the carriage ready, and drove Eliza and her boy a long, long way, through the dark night, to a cottage far in the country. There he left her with a good man and his wife, who promised to be kind to her, and help her to go to Canada. He gave some money to the good man too, and told him to use it for Eliza.

CHAPTER VI

UNCLE TOM SAYS GOOD-BYE

The day after the hunt for Eliza was a very sad one in Uncle Tom's cabin. It was the day on which Haley was going to take Uncle Tom away.

Aunt Chloe had been up very early. She had washed and ironed all Tom's clothes, and packed his trunk neatly. Now she was cooking the breakfast,—the last breakfast she would ever cook for her dear husband. Her eyes were quite red and swollen with crying, and the tears kept running down her cheeks all the time.

'It's the last time,' said Tom sadly.

Aunt Chloe could not answer. She sat down, buried her face in her hands, and sobbed aloud.

'S'pose we must be resigned. But, O Lord, how can I? If I knew anything where you was goin', or how they'd treat you! Missis says she'll try and buy you back again in a year or two. But, Lor', nobody never comes back that goes down there.'

'There'll be the same God there, Chloe, that there is here.'

'Well,' said Aunt Chloe, 's'pose dere will. But the Lord lets drefful things happen sometimes. I don't seem to get no comfort dat way.'

'Let's think on our mercies,' said Tom, in a shaking voice.

'Mercies!' said Aunt Chloe, 'don't see any mercies in 't. It isn't right! it isn't right it should be so! Mas'r never ought to have left it so that ye could be took for his debts. Mebbe he can't help himself now, but I feel it's wrong. Nothing can beat that out of me. Such a faithful crittur as ye've been, reckonin' on him more than your own wife and chil'en.'

'Chloe! now, if ye love me, you won't talk so, when it is perhaps jest the last time we'll ever have together,' said Tom.

'Wall, anyway, there's wrong about it somewhere,' said Aunt Chloe, 'I can't jest make out where 'tis. But there is wrong somewhere, I'm sure of that.'