Gardiner Samuel Rawson

A Student's History of England, v. 1: B.C. 55-A.D. 1509

22. Dispute between Wilfrid and Colman. 664.—The lesson was all the better taught because those who taught it were monks. Monasticism brought with it an extravagant view of the life of self-denial, but those who had to be instructed needed to have the lesson written plainly so that a child might read it. The rough warrior or the rough peasant was more likely to abstain from drunkenness, if he had learned to look up to men who ate and drank barely enough to enable them to live; and he was more likely to treat women with gentleness and honour, if he had learned to look up to some women who separated themselves from the joys of married life that they might give themselves to fasting and prayer. Yet, great as the influence of the clergy was, it was in danger of being lessened through internal disputes amongst themselves. A very large part of England had been converted by the Celtic missionaries, and the Celtic missionaries, though their life and teaching was in the main the same as that of the Church of Canterbury and of the Churches of the Continent, differed from them in the shape of the tonsure and in the time at which they kept their Easter. These things were themselves unimportant, but it was of great importance that the young English Church should not be separated from the Churches of more civilised countries which had preserved much of the learning and art of the old Roman Empire. One of those who felt strongly the evil which would follow on such a separation was Wilfrid. He was scornful and self-satisfied, but he had travelled to Rome, and had been impressed with the ecclesiastical memories of the great city, and with the fervour and learning of its clergy. He came back resolved to bring the customs of England into conformity with those of the churches of the Continent. On his arrival, Oswiu, in 664, gathered an assembly of the clergy of the north headed by Colman, Aidan's successor, to discuss the point. Learned arguments were poured forth on either side. Oswiu listened in a puzzled way. Wilfrid boasted that his mode of keeping Easter was derived from Peter, and that Christ had given to Peter the keys of the kingdom of heaven. Oswiu at once decided to follow Peter, lest when he came to the gate of that kingdom Peter, who held the keys, should lock him out. Wilfrid triumphed, and the English Church was in all outward matters regulated in conformity with that of Rome.

23. Archbishop Theodore and the Penitential System.—In 668, four years after Oswiu's decision was taken, Theodore of Tarsus was consecrated Archbishop of Canterbury at Rome by the Pope himself. When he arrived in England the time had come for the purely missionary stage of the English Church to come to an end. Hitherto the bishops had been few, only seven in all England. Their number was now increased, and they were set to work no longer merely to convert the heathen, but to see that the clergy did their duty amongst those who had been already converted. Gradually, under these bishops, a parochial clergy came into existence. Sometimes the freemen of a hamlet, or of two or three hamlets together, would demand the constant residence of a priest. Sometimes a lord would settle a priest to teach his serfs. The parish clergy attacked violence and looseness of life in a way different from that of the monks. The monks had given examples of extreme self-denial. Theodore introduced the penitential system of the Roman Church, and ordered that those who had committed sin should be excluded from sharing in the rites of the Church until they had done penance. They were to fast, or to repeat prayers, sometimes for many years, before they were readmitted to communion. Many centuries afterwards good men objected that these penances were only bodily actions, and did not necessarily bring with them any real repentance. In the seventh century the greater part of the population could only be reached by such bodily actions. They had never had any thought that a murder, for instance, was anything more than a dangerous action which might bring down on the murderer the vengeance of the relations of the murdered man, which might be bought off with the payment of a weregild of a few shillings. The murderer who was required by the Church to do penance was being taught that a murder was a sin against God and against himself, as well as an offence against his fellow-men. Gradually—very gradually—men would learn from the example of the monks and from the discipline of penance that they were to live for something higher than the gratification of their own passions.

Saxon church at Bradford-on-Avon, Wilts.

24. Ealdhelm and Cædmon.—When a change is good in itself, it usually bears fruit in unexpected ways. Theodore was a scholar as well as a bishop. Under his care a school grew up at Canterbury, full of all the learning of the Roman world. That which distinguished this school and others founded in imitation of it was that the scholars did not keep their learning to themselves, but strove to make it helpful to the ignorant and the poor. They learnt architecture on the Continent in order to raise churches of stone in the place of churches of wood. One of these churches is still standing at Bradford-on-Avon. Its builder was Ealdhelm, the abbot of Malmesbury, a teacher of all the knowledge of the time. Ealdhelm, learned as he was, let his heart go forth to the unlearned. Finding that his neighbours would not listen to his sermons, he sang to them on a bridge to win them to higher things. Like all people who cannot read, the English of those days loved a song. In the north, Cædmon, a rude herdsman on the lands of the abbey which in later days was known as Whitby, was vexed with himself because he could not sing. When at ale-drinkings his comrades pressed him to sing a song, he would leave his supper unfinished and return home ashamed. One night in a dream he heard a voice bidding him sing of the Creation. In his sleep the words came to him, and they remained with him when he woke. He had become a poet—a rude poet, it is true, but still a poet. The gift which Cædmon had acquired never left him. He sang of the Creation and of the whole course of God's providence. To the end he was unable to compose any songs which were not religious.

25. Bede. 673—735.—Of all the English scholars of the time Bæda, usually known as 'the venerable Bede,' was the most remarkable. He was a monk of Jarrow on the Tyne. From his youth up he was a writer on all subjects embraced by the knowledge of his day. One subject he made his own. He was the first English historian. The title of his greatest work was the Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation. He told how that nation had been converted, and of the fortunes of its Church; but for him the Church included the whole nation, and he told of the doings of kings and people, as well as of priests and monks. In this he was a true interpreter of the spirit of the English Church. Its clergy did not stand aloof from the rulers of the state, but worked with them as well as for them. The bishops stepped into the place of the heathen priests in the Witenagemots of the kings, and counselled them in matters of state as well as in matters of religion.

26. Church Councils.—Bede recognised in the title of his book that there was such a thing as an English nation long before there was any political unity. Whilst kingdom was fighting against kingdom, Theodore in 673 assembled the first English Church council at Hertford. From that time such councils of the bishops and principal clergy of all England met whenever any ecclesiastical question required them to deliberate in common. The clergy at least did not meet as West Saxons or as Mercians. They met on behalf of the whole English Church, and their united consultations must have done much to spread the idea that, in spite of the strife between the kings, the English nation was really one.

Saxon horsemen (Harl. MS. 603.)

Group of Saxon warriors. (Harl. MS. 603.)

27. Struggle between Mercia and Wessex.—Many years passed away before the kingdoms could be brought under one king. North-humberland stood apart from southern England, and during the latter half of the seventh century Wessex grew in power. Wessex had been weak because it was seldom thoroughly united. Each district was presided over by an Ætheling, or chief of royal blood, and it was only occasionally that these Æthelings submitted to the king. From time to time a strong king compelled the obedience of the Æthelings and carried on the old struggle with the western Welsh. It was not till 710 that Ine succeeded in driving the Welsh out of Somerset, and about the same time a body of the West Saxons advancing through Dorset reached Exeter. They took possession of half the city for themselves, and left the remainder to the Welsh. Ine was, however, checked by fresh outbreaks of the subordinate Æthelings, and in 726 he gave up the struggle and went on a pilgrimage to Rome. Æthelbald, king of the Mercians, took the opportunity to invade Wessex, and made himself master of the country and over-lord of all the other kingdoms south of the Humber. In 754 the West Saxons rose against him and defeated him at Burford. After a few years his successor, Offa, once more took up the task of making the Mercian king over-lord of southern England. In 775, after a long struggle, he brought Kent as well as Essex under his sway. In 779 he defeated the West Saxons at Bensington, and pushed the Mercian frontier to the Thames. Further than that Offa did not venture to go, and, great as he was, the West Saxons within their shrunken limits continued to be independent of him. He turned his arms upon the Welsh, and drove them back from the Severn to the embankment which is known from his name as Offa's Dyke. The West Saxons, being freed from attack on the side of Mercia, overran Devon. Then there was a contest for the West Saxon crown between Beorhtric and Ecgberht. Beorhtric gained the upper hand, and entered into alliance with Offa by taking his daughter to wife. Ecgberht fled to the Continent.

28. Mohammedanism and the Carolingian Empire.—A great change had passed over Europe since the days when a Frankish princess, by her marriage with the Kentish Ethelberht, had smoothed the way for the introduction of Christianity into England. In the first part of the seventh century Mohammed had preached a new religion in Arabia. He taught that there was one God, and that Mohammed was his prophet. After his death his Arab followers spread as conquerors over the neighbouring countries. Before the end of the century they had subdued Persia, Syria, and Egypt, and were pushing westwards along the north coast of Africa. In 711 they crossed the Straits of Gibraltar. All Spain, with the exception of a hilly district in the north, soon fell into their hands, and in 717 they crossed the Pyrenees. There can be little doubt that, if they had subdued Gaul, Mohammedanism and not Christianity would for a long time have been the prevailing religion in Europe. From this Europe was saved by a great Frankish warrior, Charles Martel (the Hammer), who in 732 drove the invaders back at a great battle between Tours and Poitiers. Charles's son, Pippin, dethroned the reigning family and became king of the Franks. Pippin's son was Charles the Great, who before he died ruled over the whole of Gaul and Germany, over the north and centre of Italy, and the north-east of Spain. His rule was favoured both by the Frankish warriors and by the clergy, who were glad to see so strong a bulwark erected against the attacks of the Mohammedans. At that time the Roman Empire, which had never ceased to exist at Constantinople, fell into the hands of Irene, the murderess of her son. In 800 the Pope, refusing to acknowledge that the Empire could have so unworthy a head, placed the Imperial crown on the head of Charles as the successor of the old Roman Emperors.

29. Ecgberht's Rule. 802—839.—Though Charles did not directly govern England, he made his influence felt there. Offa had claimed his protection, and Ecgberht took refuge at his court. Ecgberht doubtless learned something of the art of ruling from him, and in 802 he returned to England. Beorhtric was by this time dead, and Ecgberht was accepted as king by the West Saxons. Before he died, in 839, he had made himself the over-lord of all the other kingdoms. He was never, indeed, directly king of all England. Kent, Sussex, and Essex were governed by rulers of his own family appointed by himself. Mercia, East Anglia, and North-humberland retained their own kings, ruling under Ecgberht as their over-lord. Towards the west Ecgberht's direct government did not reach beyond the Tamar, though the Cornish Celts acknowledged his authority, as did the Celts of Wales. The Celts of Strathclyde and the Picts and Scots remained entirely independent.

CHAPTER IV.

THE ENGLISH KINGSHIP AND THE STRUGGLE WITH THE DANES

LEADING DATES

First landing of the Danes 787

Treaty of Wedmore 878

Dependent alliance of the Scots with Eadward the Elder 925

Accession of Eadgar 959

1. The West Saxon Supremacy.—It was quite possible that the power founded by Ecgberht might pass away as completely as did the power which had been founded by Æthelfrith of North-humberland or by Penda of Mercia. To some extent the danger was averted by the unusual strength of character which for six generations showed itself in the family of Ecgberht. For nearly a century and a half after Ecgberht's death no ruler arose from his line who had not great qualities as a warrior or as a ruler. It was no less important that these successive kings, with scarcely an exception, kept up a good understanding with the clergy, and especially with the Archbishops of Canterbury, so that the whole of the influence of the Church was thrown in favour of the political unity of England under the West Saxon line. The clergy wished to see the establishment of a strong national government for the protection of the national Church. Yet it was difficult to establish such a government unless other causes than the goodwill of the clergy had contributed to its maintenance. Peoples who have had little intercourse except by fighting with one another rarely unite heartily unless they have some common enemy to ward off, and some common leader to look up to in the conduct of their defence.3

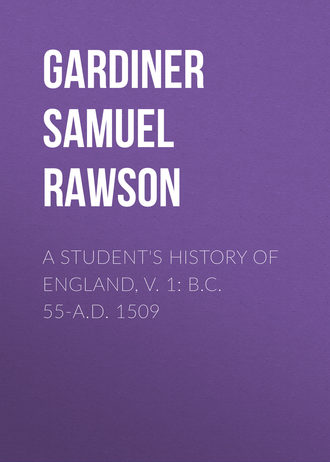

Remains of a Viking ship, from a cairn at Gokstad. (Now in the University at Christiania.)

2. The Coming of the Northmen.—The common enemy came from the north. At the end of the eighth century the inhabitants of Norway and Denmark resembled the Angles and Saxons three or four centuries before. They swarmed over the sea as pirates to plunder wherever they could find stored-up wealth along the coasts of Western Europe. The Northmen were heathen still and their religion was the old religion of force. They loved battle even more than they loved plunder. They held that the warrior who was slain in fight was received by the god Odin in Valhalla, where immortal heroes spent their days in cutting one another to pieces, and were healed of their wounds in the evening that they might join in the nightly feast, and be able to fight again on the morrow. He that died in bed was condemned to a chilly and dreary existence in the abode of the goddess Hela, whose name is the Norse equivalent of Hell.

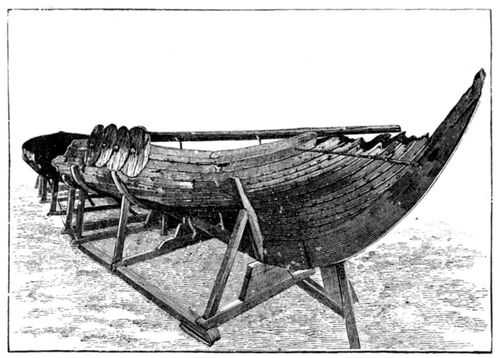

Gold ring of Æthelwulf.

3. The English Coast Plundered.—Since Englishmen had settled in England they had lost the art of seamanship. The Northmen therefore were often able to plunder and sail away. They could only be attacked on land, and some time would pass before the Ealdorman who ruled the district could gather together not only his own war-band, but the fyrd, or levy of all men of fighting age. When at last he arrived at the spot on the coast where the pirates had been plundering, he often found that they were already gone. Yet, as time went on, the Northmen took courage, and pushed far enough into the interior to be attacked before they could regain the coast. Their first landing had been in 787, before the time of Ecgberht. In Ecgberht's reign their attacks upon Wessex were so persistent that Ecgberht had to bring his own war-band to the succour of his Ealdormen. His son and successor, Æthelwulf, had a still harder struggle. The pirates spread their attacks over the whole of the southern and the eastern coast, and ventured to remain long enough on shore to fight a succession of battles. In 851 they were strong enough to remain during the whole winter in Thanet. The crews of no less than 350 ships landed in the mouth of the Thames sacked Canterbury and London. They were finally defeated by Æthelwulf at Aclea (Ockley), in Surrey. In 858 Æthelwulf died. Four of his sons wore the crown in succession; the two eldest, Æthelbald and Æthelberht, ruling only a short time.

4. The Danes in the North.—The task of the third brother, Æthelred, who succeeded in 866, was harder than his father's. Hitherto the Northmen had come for plunder, and had departed sooner or later. A fresh swarm of Danes now arrived from Denmark to settle on the land as conquerors. Though they did not themselves fight on horseback, they seized horses to betake themselves rapidly from one part of England to the other. Their first attack was made on the north, where there was no great affection for the West Saxon kings. They overcame the greater part of North-humberland. They beat down the resistance of East Anglia, and, fastening its king, Eadmund, to a tree, shot him to death with arrows. His countrymen counted him a saint, and a great monastery arose at Bury St. Edmunds in his honour. Everywhere the Danes plundered and burnt the monasteries, because the monks were weak, and their houses were rich with jewelled service books and golden plate. They next turned upon Mercia, and forced the Mercian under-king to pay tribute to them. Only Wessex, to which the smaller eastern states of Kent and Sussex had by this time been completely annexed, retained its independence.

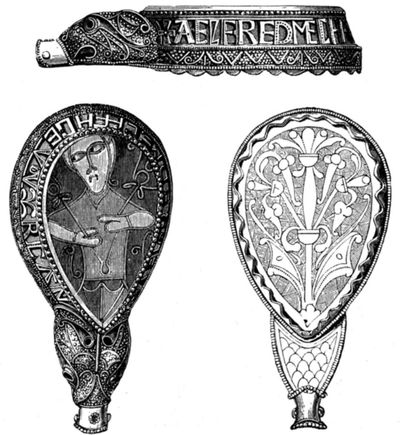

5. Ælfred's Struggle in Wessex. 871—878.—In Wessex Æthelred strove hard against the invaders. He won a great victory at Æscesdun (Ashdown, near Reading), on the northern slope of the Berkshire Downs. After a succession of battles he was slain in 871. Though he left sons of his own, he was succeeded by Ælfred, his youngest brother. It was not the English custom to give the crown to the child of a king if there was any one of the kingly family more fitted to wear it. Ælfred was no common man. In his childhood he had visited Rome, and had been hallowed as king by Pope Leo IV., though the ceremony could have had no weight in England. He had early shown a love of letters, and the story goes that when his mother offered a book with bright illuminations to the one of her children who could first learn to read it, the prize was won by Ælfred. During Æthelred's reign he had little time to give to learning. He fought nobly by his brother's side in the battles of the day, and after he succeeded him he fought nobly as king at the head of his people. In 878 the Danish host, under its king, Guthrum, beat down all resistance. Ælfred was no longer able to keep in the open country, and took refuge with a few chosen warriors in the little island of Athelney, in Somerset, then surrounded by the waters of the fen country through which the Parret flowed. After a few weeks he came forth, and with the levies of Somerset and Wilts and of part of Hants he utterly defeated Guthrum at Ethandun (? Edington, in Wiltshire), and stormed his camp.

Gold jewel of Ælfred found at Athelney. (Now in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.)

6. The Treaty of Chippenham, and its Results. 878.—After this defeat Guthrum and the Danes swore to a peace with Ælfred at Chippenham. They were afterwards baptised in a body at Aller, not far from Athelney. Guthrum with a few of his companions then visited Ælfred at Wedmore, a village near the southern foot of the Mendips, from which is taken the name by which the treaty is usually but wrongly known. By this treaty Ælfred retained no more than Wessex, with its dependencies, Sussex and Kent, and the western half of Mercia. The remainder of England as far north as the Tees was surrendered to the Danes, and became known as the Danelaw, because Danish and not Saxon law prevailed in it. Beyond the Tees Bernicia maintained its independence under an English king. Though the English people never again had to struggle for its very existence as a political body, yet, in 886, after a successful war, Ælfred wrung from Guthrum a fresh treaty by which the Danes surrendered London and the surrounding district. Yet, even after this second treaty, it might seem as if Ælfred, who only ruled over a part of England, was worse off than his grandfather, Ecgberht, who had ruled over the whole. In reality he was better off. In the larger kingdom it would have been almost impossible to produce the national spirit which alone could have permanently kept the whole together. In the smaller kingdom it was possible, especially as there was a strong West Saxon element in the south-west of Mercia in consequence of its original settlement by a West Saxon king after the battle of Deorham (see p. 35). Moreover, Ælfred, taking care not to offend the old feeling of local independence which still existed in Mercia, appointed his son-in-law, Æthelred, who was a Mercian, to govern it as an ealdorman under himself.

An English vessel. (Harl. MS. 603.)

7. Ælfred's Military Work.—Ælfred would hardly have been able to do so much unless his own character had been singularly attractive. Other men have been greater warriors or legislators or scholars than Ælfred was, but no man has ever combined in his own person so much excellence in war, in legislation, and in scholarship. As to war, he was not only a daring and resolute commander, but he was an organiser of the military forces of his people. One chief cause of the defeats of the English had been the difficulty of bringing together in a short time the 'fyrd,' or general levy of the male population, or of keeping it long together when men were needed at home to till the fields. Ælfred did his best to overcome this difficulty by ordering that half the men of each shire should be always ready to fight, whilst half remained at home. This new half-army, like his new half-kingdom, was stronger than the whole one had been before. To an improved army Ælfred added a navy, and he was the first English king who defeated the Danes at sea.

A Saxon house. (Harl. MS. 603.)

8. His Laws and Scholarship.—Ælfred was too great a man to want to make every one conform to some ideal of his own choosing. It was enough for him to take men as they were, and to help them to become better. He took the old laws and customs, and then, suggesting a few improvements, submitted them to the approval of his Witenagemot, the assembly of his bishops and warriors. He knew also that men's conduct is influenced more by what they think than by what they are commanded to do. His whole land was steeped in ignorance. The monasteries had been the schools of learning; and many of them had been sacked by the Danes, their books burnt, and their inmates scattered, whilst others were deserted, ceasing to receive new inmates because the first duty of Englishmen had been to defend their homes rather than to devote themselves to a life of piety. Latin was the language in which the services of the Church were read, and in which books like Bede's Ecclesiastical History were written. Without a knowledge of Latin there could be no intercourse with the learned men of the Continent, who used that language still amongst themselves. Yet when the Danes departed from Ælfred's kingdom, there were but very few priests who could read a page of Latin. Ælfred did his best to remedy the evil. He called learned men to him wherever they could be found. Some of these were English; others, like Asser, who wrote Ælfred's life, were Welsh; others again were Germans from beyond the sea. Yet Ælfred was not content. It was a great thing that there should be again schools in England for those who could write and speak Latin, the language of the learned, but his heart yearned for those who could not speak anything but their own native tongue. He set himself to be the teacher of these. He himself translated Latin books for them, with the object of imparting knowledge, not of giving, as a modern translator would do, the exact sense of the author. When, therefore, he knew anything which was not in the books, but which he thought it good for Englishmen to read, he added it to his translation. Even with this he was not content. The books of Latin writers which he translated taught men about the history and geography of the Continent. They taught nothing about the history of England itself, of the deeds and words of the men who had ruled the English nation. That these things might not be forgotten, he bade his learned men bring together all that was known of the history of his people since the day when they first landed as pirates on the coast of Kent. The Chronicle, as it is called, is the earliest history which any European nation possesses in its own tongue. Yet, after all, such a man as Ælfred is greater for what he was than for what he did. No other king ever showed forth so well in his own person the truth of the saying, 'He that would be first among you, let him be the servant of all.'

9. Eadward the Elder. 899—925.—In 899 Ælfred died. He had already fortified London as an outpost against the Danes, and he left to his son, Eadward, a small but strong and consolidated kingdom. The Danes on the other side of the frontier were not united. Guthrum's kingdom stretched over the old Essex and East Anglia, as well as over the south-eastern part of the old Mercia. The land from the Humber to the Nen was under the rule of Danes settled in the towns known to the English as the Five boroughs of Derby, Leicester, Lincoln, Stamford, and Nottingham. In the old Deira or modern Yorkshire was a separate Danish kingdom. Danes, in short, settled wherever we now find the place-names, such as Derby and Whitby, ending in the Danish termination 'by' instead of in the English terminations 'ton' or 'ham,' as in Luton and Chippenham. Yet even in these parts the bulk of the population was usually English, and the English population would everywhere welcome an English conqueror. A century earlier a Mercian or a North-humbrian had preferred independence to submission to a West Saxon king. They now preferred a West Saxon king to a Danish master, especially as the old royal houses were extinct, and there was no one but the West Saxon king to lead them against the Danes.

10. Eadward's Conquests.—Eadward was not, like his father, a legislator or a scholar, but he was a great warrior. In a series of campaigns he subdued the Danish parts of England as far north as the Humber. He was aided by his brother-in-law, Æthelred, and after Æthelred's death by his own sister, Æthelred's widow, Æthelflæd, the Lady of the Mercians, one of the few warrior-women of the world. Step by step the brother and sister won their way, not contenting themselves with victories in the open country, but securing each district as they advanced by the erection of 'burhs' or fortifications. Some of these 'burhs' were placed in desolate Roman strongholds, such as Chester. Others were raised, like that of Warwick, on the mounds piled up in past times by a still earlier race. Others again, like that of Stafford, were placed where no fortress had been before. Towns, small at first, grew up in and around the 'burhs,' and were guarded by the courage of the townsmen themselves. Eadward, after his sister's death, took into his own hands the government of Mercia, and from that time all southern and central England was united under him. In 922 the Welsh kings acknowledged his supremacy.

11. Eadward and the Scots.—Tradition assigns to Eadward a wider rule shortly before his death. In the middle of the ninth century the Picts and the intruding Scots (see p. 42) had been amalgamated under Keneth MacAlpin, the king of the Scots, and the new kingdom had since been welded together, just as Mercia and Wessex were being welded together by the attacks of the Danes. It is said that in 925 the king of the Scots, together with other northern rulers, chose Eadward 'to father and lord.' Probably this statement only covers some act of alliance formed by the English king with the king of Scots and other lesser rulers. Nothing was more natural than that the Scottish king, Constantine, should wish to obtain the support of Eadward against his enemies; and it was also natural that if Eadward agreed to support him, he would require some acknowledgment of the superiority of the English king; but what was the precise form of the acknowledgment must remain uncertain. In 925 Eadward died.

12. Æthelstan. 925—940.—Three sons of Eadward reigned in succession. The eldest, of illegitimate birth, was Æthelstan. Sihtric, the Danish king at York, owned him as over-lord, and on Sihtric's death in 926, Æthelstan took Danish North-humberland under his direct rule. The Welsh kings were reduced to make a fuller acknowledgment of his supremacy than they had made to his father. He drove the Welsh out of the half of Exeter which had been left to them, and confined them to the modern Cornwall beyond the Tamar. Great rulers on the Continent sought his alliance. The empire of Charles the Great had broken up. One of Æthelstan's sisters was given to Charles the Simple, the king of the Western Franks; another to Hugh the Great, Duke of the French and lord of Paris, who, though nominally the vassal of the king, was equal in power to his lord, and whose son was afterwards the first king of modern France. A third sister was given to Otto, the son of Henry, the king of the Eastern Franks, from whom, in due time, sprang a new line of Emperors. Æthelstan's greatness drew upon him the jealousy of the king of the Scots and of all the northern kings. In 937 he defeated them all in a great battle at Brunanburh, of which the site is unknown. His victory was celebrated in a splendid war-song.