Gardiner Samuel Rawson

A Student's History of England, v. 1: B.C. 55-A.D. 1509

19. Government of Suetonius Paullinus. 58.—When Suetonius Paullinus arrived to take up the government, he resolved to complete the conquest of the west by an attack on Mona (Anglesey). In Mona was a sacred place of the Druids, who gave encouragement to the still independent Britons by their murderous sacrifices and their soothsayings. When Suetonius attempted to land (61), a rabble of women, waving torches and shrieking defiance, rushed to meet him on the shore. Behind them the Druids stood calling down on the intruders the vengeance of the gods. At first the soldiers were terrified and shrunk back. Then they recovered courage, and put to the sword or thrust into the flames the priests and their female rout. The Romans were tolerant of the religion of the peoples whom they subdued, but they could not put up with the continuance of a cruel superstition whose upholders preached resistance to the Roman government.

20. Boadicea's Insurrection. 61.—At the very moment of success Suetonius was recalled hurriedly to the east. Roman officers and traders had misused the power which had been given them by the valour of Roman soldiers. Might had been taken for right, and the natives were stripped of their lands and property at the caprice of the conquerors. Those of the natives to whom anything was left were called upon to pay a taxation far too heavy for their means. When money was not to be found to satisfy the tax-gatherer, a Roman usurer was always at hand to proffer the required sum at enormous interest, after which the unhappy borrower who accepted the proposal soon found himself unable to pay the debt, and was stripped of all that he possessed to satisfy the cravings of the lender. Those who resisted this oppression were treated as the meanest criminals. Boadicea, the widow of Prasutagus, who had been the chief of the Iceni, was publicly flogged, and her two daughters were subjected to the vilest outrage. She called upon the whole Celtic population of the east and south to rise against the foreign tyrants. Thousands answered to her call, and the angry host rushed to take vengeance upon the colonists of Camulodunum. The colonists had neglected to fortify their city, and the insurgents, bursting in, slew by the sword or by torture men and women alike. The massacre spread wherever Romans were to be found. A Roman legion hastening to the rescue was routed, and the small force of cavalry attached to it alone succeeded in making its escape. Every one of the foot soldiers was slaughtered on the spot. It is said that 70,000 Romans perished in the course of a few days.

21. The Vengeance of Suetonius.—Suetonius was no mean general, and he hastened back to the scene of destruction. He called on the commander of the legion at Isca Silurum to come to his help. Cowardice was rare in a Roman army, but this officer was so unnerved by terror that he refused to obey the orders of his general, and Suetonius had to march without him. He won a decisive victory at some unknown spot, probably not far from Camulodunum, and 80,000 Britons are reported to have been slain by the triumphant soldiery. Boadicea committed suicide by poison. The commander of the legion at Isca Silurum also put an end to his own life, in order to escape the punishment which he deserved. Suetonius had restored the Roman authority in Britain, but it was to his failure to control his subordinates that the insurrection had been due, and he was therefore promptly recalled by the Emperor Nero. From that time no more is heard of the injustice of the Roman government.

22. Agricola in Britain. 78—84.—Agricola, who arrived as governor in 78, took care to deal fairly with all sorts of men, and to make the natives thoroughly satisfied with his rule. He completed the conquest of the country afterwards known as Wales, and thereby pushed the western frontier of Roman Britain to the sea. Yet from the fact that he found it necessary still to leave garrisons at Deva and Isca Silurum, it may be gathered that the tribes occupying the hill country were not so thoroughly subdued as to cease to be dangerous. Although the idea entertained by Ostorius of making a frontier on land towards the west had thus been abandoned, it was still necessary to provide a frontier towards the north. Even before Agricola arrived it had been shown to be impossible to stop at the line between the Mersey and the Humber. Beyond that line was the territory of the Brigantes, who had for some time occupied the position which in the first years of the Roman conquest had been occupied by the Iceni—that is to say, they were in friendly dependence upon Rome, without being actually controlled by Roman authority. Before Agricola's coming disputes had arisen with them, and Roman soldiers had occupied their territory. Agricola finished the work of conquest. He now governed the whole of the country as far north as to the Solway and the Tyne, and he made Eboracum, the name of which changed in course of time into York, the centre of Roman power in the northern districts. A garrison was established there to watch for any danger which might come from the extreme north, as the garrisons of Deva and Isca Silurum watched for dangers which might come from the west.

23. Agricola's Conquests in the North.—Agricola thought that there would be no real peace unless the whole island was subdued. For seven years he carried on warfare with this object before him. He had comparatively little difficulty in reducing to obedience the country south of the narrow isthmus which separates the estuary of the Clyde from the estuary of the Forth. Before proceeding further he drew a line of forts across that isthmus to guard the conquered country from attack during his absence. He then made his way to the Tay, but he had not marched far up the valley of that river before he reached the edge of the Highlands. The Caledonians, as the Romans then called the inhabitants of those northern regions, were a savage race, and the mountains in the recesses of which they dwelt were rugged and inaccessible, offering but little means of support to a Roman army. In 84 the Caledonians, who, like all barbarians when they first come in contact with a civilised people, were ignorant of the strength of a disciplined army, came down from their fortresses in the mountains into the lower ground. A battle was fought near the Graupian Hill, which seems to have been situated at the junction of the Isla and the Tay. Agricola gained a complete victory, but he was unable to follow the fugitives into their narrow glens, and he contented himself with sending his fleet to circumnavigate the northern shores of the island, so as to mark out the limits of the land which he still hoped to conquer. Before the fleet returned, however, he was recalled by the Emperor Domitian. It has often been said that Domitian was jealous of his success; but it is possible that the Emperor really thought that the advantage to be gained by the conquest of rugged mountains would be more than counterbalanced by the losses which would certainly be incurred in consequence of the enormous difficulty of the task.

Commemorative tablet of the Second Legion found at Halton Chesters on the Roman Wall.

24. The Roman Walls.—Agricola, in addition to his line of forts between the Forth and the Clyde, had erected detached forts at the mouth of the valleys which issue from the Highlands, in order to hinder the Caledonians from plundering the lower country. In 119 the Emperor Hadrian visited Britain. He was more disposed to defend the Empire than to extend it, and though he did not abandon Agricola's forts, he also built further south a continuous stone wall between the Solway and the Tyne. This wall, which, together with an earthwork of earlier date, formed a far stronger line of defence than the more northern forts, was intended to serve as a second barrier to keep out the wild Caledonians if they succeeded in breaking through the first. At a later time a lieutenant of the Emperor, Antoninus Pius, who afterwards became Emperor himself, connected Agricola's forts between the Forth and Clyde by a continuous earthwork. In 208 the Emperor Severus arrived in Britain, and after strengthening still further the earthwork between the Forth and Clyde, he attempted to carry out the plans of Agricola by conquering the land of the Caledonians. Severus, however, failed as completely as Agricola had failed before him, and he died soon after his return to Eboracum.

View of part of the Roman Wall.

Ruins of a Turret on the Roman Wall.

Part of the Roman Wall at Leicester.

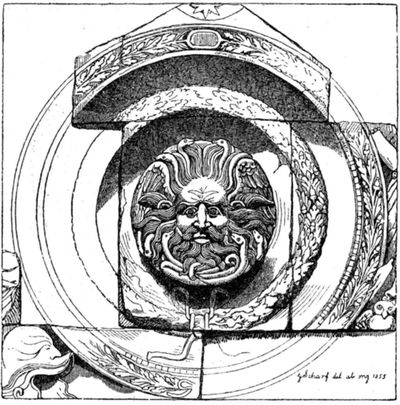

Pediment of a Roman temple found at Bath.

25. The Roman Province of Britain.—Very little is known of the history of the Roman province of Britain, except that it made considerable progress in civilisation. The Romans were great road-makers, and though their first object was to enable their soldiers to march easily from one part of the country to another, they thereby encouraged commercial intercourse. Forests were to some extent cleared away by the sides of the new roads, and fresh ground was thrown open to tillage. Mines were worked and country houses built, the remains of which are in some places still to be seen, and bear testimony to the increased well-being of a population which, excepting in the south-eastern part of the island, had at the arrival of the Romans been little removed from savagery. Cities sprang up in great numbers. Some of them were at first garrison towns, like Eboracum, Deva, and Isca Silurum. Others, like Verulamium, near the present St. Albans, occupied the sites of the old stockades once used as places of refuge by the Celts, or, like Lindum, on the top of the hill on which Lincoln Cathedral now stands, were placed in strongly defensible positions. Aquæ Sulis, the modern Bath, owes its existence to its warm medicinal springs. The chief port of commerce was Londinium, the modern London. Attempts which have been made to explain its name by the Celtic language have failed, and it is therefore possible that an inhabited post existed there even before the Celts arrived. Its importance was, however, owing to its position, and that importance was not of a kind to tell before a settled system of commercial intercourse sprang up. London was situated on the hill on which St. Paul's now stands. There first, after the Thames narrowed into a river, the merchant found close to the stream hard ground on which he could land his goods. The valley for some distance above and below it was then filled with a wide marsh or an expanse of water. An old track raised above the marsh crossed the river by a ford at Lambeth, but, as London grew in importance, a ferry was established where London Bridge now stands, and the Romans, in course of time, superseded the ferry by a bridge. It is, therefore, no wonder that the Roman roads both from the north and from the south converged upon London. Just as Eboracum was a fitting centre for military operations directed to the defence of the northern frontier, London was the fitting centre of a trade carried on with the Continent, and the place would increase in importance in proportion to the increase of that trade.

Roman altar from Rutchester.

26. Extinction of Tribal Antagonism.—The improvement of communications and the growth of trade and industry could not fail to influence the mind of the population. Wars between tribes, which before the coming of the Romans had been the main employment of the young and hardy, were now things of the past. The mutual hatred which had grown out of them had died away, and even the very names of Trinobantes and Brigantes were almost forgotten. Men who lived in the valley of the Severn came to look upon themselves as belonging to the same people as men who lived in the valleys of the Trent or the Thames. The active and enterprising young men were attracted to the cities, at first by the novelty of the luxurious habits in which they were taught to indulge, but afterwards because they were allowed to take part in the management of local business. In the time of the Emperor Caracalla, the son of Severus, every freeman born in the Empire was declared to be a Roman citizen, and long before that a large number of natives had been admitted to citizenship. In each district a council was formed of the wealthier and more prominent inhabitants, and this council had to provide for the building of temples, the holding of festivals, the erection of fortifications, and the laying out of streets. Justice was done between man and man according to the Roman law, which was the best law that the world had seen, and the higher Roman officials, who were appointed by the Emperor, took care that justice was done between city and city. No one therefore, wished to oppose the Roman government or to bring back the old times of barbarism.

27. Want of National Feeling.—Great as was the progress made, there was something still wanting. A people is never at its best unless those who compose it have some object for which they can sacrifice themselves, and for which, if necessary, they will die. The Briton had ceased to be called upon to die for his tribe, and he was not expected to die for Britain. Britain had become a more comfortable country to live in, but it was not the business of its own inhabitants to guard it. It was a mere part of the vast Roman Empire, and it was the duty of the Emperors to see that the frontier was safely kept. They were so much afraid lest any particular province should wish to set up for itself and to break away from the Empire, that they took care not to employ soldiers born in that province for its protection. They sent British recruits to guard the Danube or the Euphrates, and Gauls, Spaniards, or Africans to guard the wall between the Solway and the Tyne, and the entrenchment between the Forth and the Clyde. Britons, therefore, looked on their own defence as something to be done for them by the Emperors, not as something to be done by themselves. They lived on friendly terms with one another, but they had nothing of what we now call patriotism.

28. Carausius and Allectus. 288—296.—In 288 Carausius, with the help of some pirates, seized on the government of Britain and threw off the authority of the Emperor. He was succeeded by Allectus, yet neither Carausius nor Allectus thought of making himself the head of a British nation. They called themselves Emperors and ruled over Britain alone, merely because they could not get more to rule over.

29. Constantius and Constantine. 296—337.—Allectus was overthrown and slain by Constantius, who, however, did not rule, as Carausius and Allectus had done, by mere right of military superiority. The Emperor Diocletian (285—305) discovered that the whole Empire, stretching from the Euphrates to the Atlantic, was too extensive for one man to govern, and he therefore decreed that there should in future be four governors, two principal ones named Emperors (Augusti), and two subordinate ones named Cæsars. Constantius was first a Cæsar and afterwards an Emperor. He was set to govern Spain, Gaul, and Britain, but he afterwards became Emperor himself, and for some time established himself at Eboracum (York). Upon his death (306), his son Constantine, after much fighting, made himself sole Emperor (325), overthrowing the system of Diocletian. Yet in one respect he kept up Diocletian's arrangements. He placed Spain, Gaul, and Britain together under a great officer called a Vicar, who received orders from himself and who gave orders to the officers who governed each of the three countries. Under the new system, as under the old, Britain was not treated as an independent country. It had still to look for protection to an officer who lived on the Continent, and was therefore apt to be more interested in Gaul and Spain than he was in Britain.

30. Christianity in Britain.—When the Romans put down the Druids and their bloody sacrifices, they called the old Celtic gods by Roman names, but made no further alteration in religious usages. Gradually, however, Christianity spread amongst the Romans on the Continent, and merchants or soldiers who came from the Continent introduced it into Britain. Scarcely anything is known of its progress in the island. Alban is said to have been martyred at Verulamium, and Julius and Aaron at Isca Silurum. In 314 three British bishops attended a council held at Arles in Gaul. Little more than these few facts have been handed down, but there is no doubt that there was a settled Church established in the island. The Emperor Constantine acknowledged Christianity as the religion of the whole Empire. The remains of a church of this period have recently been discovered at Silchester.

31. Weakness of the Empire.—The Roman Empire in the time of Constantine had the appearance rather than the reality of strength. Its taxation was very heavy, and there was no national enthusiasm to lead men to sacrifice themselves in its defence. Roman citizens became more and more unwilling to become soldiers at all, and the Roman armies were now mostly composed of barbarians. At the same time the barbarians outside the Empire were growing stronger, as the tribes often coalesced into wide confederacies for the purpose of attacking the Empire.

32. The Picts and Scots.—The assailants of Britain on the north and the west were the Picts and Scots. The Picts were the same as the Caledonians of the time of Agricola. We do not know why they had ceased to be called Caledonians. The usual derivation of their name from the Latin Pictus, said to have been given them because they painted their bodies, is inaccurate. Opinions differ whether they were Goidels with a strong Iberian strain, or Iberians with a Goidelic admixture. They were probably Iberians, and at all events they were more savage than the Britons had been before they were influenced by Roman civilisation. The Scots, who afterwards settled in what is now known as Scotland, at that time dwelt in Ireland. Whilst the Picts, therefore, assailed the Roman province by land, and strove, not always unsuccessfully, to break through the walls which defended its northern frontier, the Scots crossed the Irish Sea in light boats to plunder and slay before armed assistance could arrive.

33. The Saxons.—The Saxons, who were no less deadly enemies of the Roman government, were as fierce and restless as the Picts and Scots, and were better equipped and better armed. At a later time they established themselves in Britain as conquerors and settlers, and became the founders of the English nation; but at first they were only known as cruel and merciless pirates. In their long flat-bottomed vessels they swooped down upon some undefended part of the coast and carried off not only the property of wealthy Romans, but even men and women to be sold in the slave-market. The provincials who escaped related with peculiar horror how the Saxons were accustomed to torture to death one out of every ten of their captives as a sacrifice to their gods.

34. Origin of the Saxons.—The Saxons were the more dangerous because it was impossible for the Romans to reach them in their homes. They were men of Teutonic race, speaking one of the languages, afterwards known as Low German, which were once spoken in the whole of North Germany. The Saxon pirates were probably drawn from the whole of the sea coast stretching from the north of the peninsula of Jutland to the mouth of the Ems, and if so, there were amongst them Jutes, whose homes were in Jutland itself; Angles, who inhabited Schleswig and Holstein; and Saxons, properly so called, who dwelt about the mouth of the Elbe and further to the west. All these peoples afterwards took part in the conquest of southern Britain, and it is not unlikely that they all shared in the original piratical attacks. Whether this was the case or not, the pirates came from creeks and inlets outside the Roman Empire, whose boundary was the Rhine, and they could therefore only be successfully repressed by a power with a good fleet, able to seek out the aggressors in their own homes and to stop the mischief at its source.

35. The Roman Defence.—The Romans had always been weak at sea, and they were weaker now than they had been in earlier days. They were therefore obliged to content themselves with standing on the defensive. Since the time of Severus, Britain had been divided, for purposes of defence, into Upper and Lower Britain. Though there is no absolute certainty about the matter, it is probable that Upper Britain comprised the hill country of the west and north, and that Lower Britain was the south-eastern part of the island, marked off by a line drawn irregularly from the Humber to the Severn.1 Lower Britain in the early days of the Roman conquest had been in no special need of military protection. In the fourth century it was exposed more than the rest of the island to the attacks of the Saxon pirates. Fortresses were erected between the Wash and Beachy Head at every point at which an inlet of the sea afforded an opening to an invader. The whole of this part of the coast became known as the Saxon Shore, because it was subjected to attacks from the Saxons, and a special officer known as the Count of the Saxon Shore was appointed to take charge of it. An officer known as the Duke of the Britains (Dux Britanniarum) commanded the armies of Upper Britain; whilst a third, who was a civilian, and superior in rank over the other two, was the Count of Britain, and had a general supervision of the whole country.

36. End of the Roman Government. 383—410.—In 383 Maximus, who was probably the Duke of the Britains, was proclaimed Emperor by his soldiers. If he could have contented himself with defending Britain, it would have mattered little whether he chose to call himself an Emperor or a Duke. Unhappily for the inhabitants of the island, not only did every successful soldier want to be an Emperor, but every Emperor wanted to govern the whole Empire. Maximus, therefore, instead of remaining in Britain, carried a great part of his army across the sea to attempt a conquest of Gaul and Spain. Neither he nor his soldiers ever returned, and in consequence the Roman garrison in the island was deplorably weakened. Early in the fifth century an irruption of barbarians gave full employment to the army which defended Gaul, so that it was impossible to replace the forces which had followed Maximus by fresh troops from the Continent. The Roman Empire was in fact breaking up. The defence of Britain was left to the soldiers who remained in the island, and in 409 they proclaimed a certain Constantine Emperor. Constantine, like Maximus, carried his soldiers across the Channel in pursuit of a wider empire than he could find in Britain. He was himself murdered, and his soldiers, like those of Maximus, did not return. In 410 the Britons implored the Emperor Honorius to send them help. Honorius had enough to do to ward off the attacks of barbarians nearer Rome, and announced to the Britons that they must provide for their own defence. From this time Britain ceased to form part of the Roman Empire.