Baring-Gould Sabine

A History of Sarawak under Its Two White Rajahs 1839-1908

Apart from this tendency, when under control the Malay character has much in common with the Mongol, being, under ordinary circumstances, gentle, peaceable, obedient, and loyal, but at the same time proud and sensitive, and with strangers suspicious and reserved.

The Malays can be faithful and trustworthy, and they are active and clever. Serious crime among them is not common now, nor is thieving. They have a bad propensity of running into debt, and obtaining advances under engagements which they never fulfil. They make good servants and valuable policemen. All the Government steamers are officered and manned throughout by Malays, and none could desire to have better crews. They are the principal fishermen and woodsmen. Morality is perhaps not a strong point with them, but drinking is exceptional, and gambling is not as prevalent as it was, nor do they indulge in opium smoking.

With regard to the Chinaman, it will be well to let the present Rajah speak from his own experience. He says that —

John Chinaman as a race are an excellent set of fellows, and a poor show would these Eastern countries make without their energetic presence. They combine many good, many dangerous, and it must be admitted, many bad qualities. They are given to be overbearing and insolent (unless severely kept down) nearly to as great a degree as Europeans of the rougher classes. They will cheat their neighbours and resort to all manner of deception on principle. But their redeeming qualities are comparative charitableness and liberality; a fondness for improvements; and, except in small mercantile affairs or minor trading transactions, they are honest.

They, in a few words, possess the wherewithal to be good fellows, and are more fit to be compared to Europeans than any other race of Easterns.

They have been excluded as much as possible from gaining a footing in Batavia,38 under the plea of their dangerous and usurious pursuits; but the probability is that they would have raised an unpleasant antagonism in the question of competition in that country. The Chinaman would be equal to the Master, or White Man, if both worked fairly by the sweat of his brow. As for their usury, it is not of so dangerous a character as that which prevails among the Javanese and the natives.

Upon my first arrival I was strongly possessed by the opinion that the Chinamen were all rascals and thieves – the character so generally attached to the whole race at home. But to be candid, and looking at both sides, I would as soon deal with a Chinese merchant in the East as with one who is European, and I believe the respectable class of Chinese to be equal in honesty and integrity to the white man.

The Chinese may be nearly as troublesome a people to govern as Europeans, certainly not more so; and their good qualities, in which they are not deficient, should be cherished and stimulated, while their bad ones are regulated by the discipline of the law under a just and liberal government. They are a people specially amenable to justice, and are happier under a stringent than a lenient system.

Of the Chinese the Sarawak Gazette (November 1, 1897) says: —

The characteristics of this extraordinary people must at once strike the minds of the most superficial of European residents in the East. Their wonderful energy and capacity for work; their power of accumulating wealth; their peculiar physical powers, which render them equally fertile, and their children equally vivacious, on the equator as in more temperate regions, and which enable them to rear a new race of natives under climatic conditions entirely different from those under which their forefathers were born, are facts with which we are all acquainted. Their mental endowments, too, are by no means to be despised, as nearly every year shows us, when the results of the examination for the Queen's Scholarship of the Straits Settlements are published, and some young Chinese boy departs for England to enter into educational competition with his European fellows.

Chinese get on well with all natives, with whom they intermarry, the mixed offspring being a healthy and good-looking type. They form the merchant, trading, and artisan classes, and they are the only agriculturists and mine labourers of any worth. Without these people a tropical country would remain undeveloped.

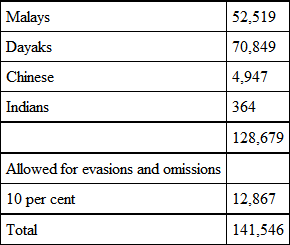

The only census that appears to have been attempted in Sarawak was taken in 1871. Judging by the report that was published in the Gazette this census was made in a very imperfect manner.39 Of the interior population it includes Sea-Dayaks, but no means were obtainable for ascertaining the numbers of Kayans, Kenyahs, and many other tribes that go to make up the population of the State. It makes no separate mention of the large coast population of the Melanaus, who were presumably lumped with the Malays.

The census gives the following figures: —

The report concedes it was the generally received opinion that the population was nearer 200,000, and if we include the Kayans, Kenyahs, etc., and accept the approximate correctness of the above figures, that estimate would be about correct.

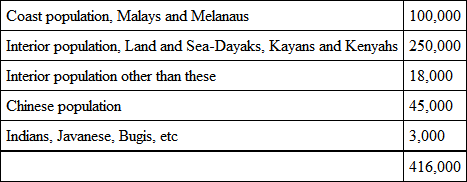

In 1871, the State extended as far as Kedurong Point only, but since that the territorial area has been nearly doubled. The population is now estimated at 500,000, though this is probably too liberal a calculation, and the following is a fairer estimate: —

The names by which the various tribes are known are those given to them by others, mostly by the coast people, or are taken from the name of the river on which they reside, or from which they came. Daya (as it should be spelt, and as it is pronounced) in the Melanau and Bruni Malay dialect means "land," "in-land." So we have Orang daya, an inlander. Ka-daya-an is contracted into Kayan; Ukit and Bukitan are from the Malay word bukit– a hill; and tanjong is the Malay for a cape or a point round which a river sweeps. Hence Orang Ukit or Bukitan, a hill-man,40 and Orang Tanjong, riverside people.

As in ancient Germany the districts were known by the names of the rivers that watered them, and each was a gau, so it is in Borneo, where the rivers are the roads of communication, and give their names to the districts and to the people that inhabit them. Indeed, in Borneo one can see precisely at this day what was the ancient Gau-verfassung in the German Empire.

The area of Sarawak is about 50,000 square miles, and the coast line about 500 miles.

The climate is hot and humid; it is especially moist during the N.E. monsoon, and less so during the S.W. monsoon. The former commences and the latter ends sometimes early and sometimes late in October, and in April the seasons again change. The months of most rain are December, January, and February; from February the rainfall decreases until July, the month of least rain, and increases gradually after that month. The average yearly rainfall is 160 inches. The maximum in any one year, 225.95 inches, was recorded in 1882, and the minimum 102.4 in 1888. The heaviest rainfall for one month, 69.25 inches, occurred in January, 1881, and the least,66 inches, in August, 1877. The most in one day was 15.3 inches on February 8, 1876. Rain falls on an average 226 days in the year. These notes are taken from observations made in Kuching extending over thirty years.41 At Sibu, the average rainfall for five years was 116 inches, at Baram 92 inches, and at Trusan 167 inches. Except in the sun at mid-day and during the early hours of the afternoon the heat is hardly ever oppressive, and the mornings, evenings and nights are generally cool. In 1906, the maximum average temperature was 91°.6, and the minimum 71°.2 Fahrenheit; the highest reading was 94° in May, and the lowest 69°.6 in July.42

In few countries are thunderstorms more severe than in Borneo, but deaths from lightning are not very common, and hail falls so rarely that when it does fall it is an awe-inspiring object to some natives. Archdeacon Perham records that during a very severe hailstorm in 1874 some Dayaks collected the hailstones under the impression that they were rare charms, whilst others fled from their house, believing that everybody and everything in it would be turned into a petrified rock, a woeful monument to future generations. To avert this catastrophe they boiled the hailstones and burnt locks of their hair.43

CHAPTER II

EARLY HISTORY

Borneo was known to the Arabs many centuries ago, and Sinbad the Sailor was fabled to have visited the island. It was then imagined that a ship might be freighted there with pearls, gold, camphor, gums, perfumed oils, spices, and gems, and this was not far from the truth.

When Genghis Khan conquered China, and founded his mighty Mogul Empire (1206-27), it is possible that he extended his rule over Borneo, where Chinese had already settled. Kublai Khan is said to have invaded Borneo with a large force in 1292; and that a Chinese province was subsequently established in northern Borneo, in which the Sulu islands were included, is evidenced by Bruni and Sulu traditions. The Celestials have left their traces in the name of Kina Balu (the Chinese Widow) given to the noble peak in the north of the island,44 and of the rivers Kina-batangan (the Chinese river) and Kina-bangun on the east coast of Borneo, and certain jars, mentioned in chapter I. p. 26, ornamented with the royal dragon of China, are treasured as heirlooms by the Dayaks. At Santubong, at the mouth of the Sarawak river, Chinese coins dating back to B.C. 600 and 112, and from A.D. 588 and onwards, have been found, with many fragments of Chinese pottery. The name Santubong is itself Chinese, San-tu-bong, meaning the "King of the Jungle" in the Kheh dialect, and the "Mountain of wild pig" in the Hokien dialect.

Besides the antique jars, the art of making which appears to have been lost, further evidence of an ancient Chinese trade may be found in the old and peculiar beads so treasured by the Kayans and Kenyahs. These are generally supposed to be Venetian, and to have been introduced by the Portuguese. Beccari (op. cit. p. 263) mentions that he had heard or read that the Malay word for a bead, manit (pronounced maneet), was a corruption of the Italian word moneta (money), which was used for glass beads at the time when the Venetians were the foremost traders in the world. But he points out "that the Venetians made their beads in imitation of the Chinese, who it appears had used them from the remotest times in their commercial transactions with the less civilized tribes of Southern Asia and the Malay islands." And it was by the Chinese these beads were probably introduced into Borneo; manit is but the Sanskrit word mani, meaning a bead.45

From the Kina-batangan river came the Chinese wife of Akhmed, the second Sultan of Bruni. She was the daughter of Ong Sum Ping, a Chinese envoy, and from her and Sultan Akhmed the Bruni sultans down to the present day, and for over twenty generations, trace their descent on the distaff side, for their daughter married the Arab Sherip Ali, who became Sultan in succession to his father-in-law, and they were the founders of the present dynasty.46 Sulu chronicles contain the same legend; and according to these Ong Sum Ping, or Ong Ti Ping, settled in the Kina-batangan A.D. 1375. He was probably a governor in succession to others.

The Hindu-Javan empire of Majapahit in Java certainly extended over Borneo, but it left there no such stately temples and palaces as those that remain in Java, and the only reminiscences of the Hindu presence in Sarawak are the name of a god, Jewata,47 which lingers among the Dayaks, a mutilated stone bull, two carved stones like the lingams of the Hindus; and at Santubong, on a large immovable rock situated up a small stream, is a rudely carved statue of a human figure nearly life-size, with outstretched arms, lying flat, face downwards, in an uncouth position, perhaps commemorative of some crime.48

Santubong is at the eastern mouth of the Sarawak river, and is prettily situated just inside the entrance, and at the foot of the isolated peak bearing the same name, which rises boldly out of the sea to a height of some 3000 feet. This place, which apparently was once a Chinese, and then a Hindu-Javan colony, is now a small fishing hamlet only, with a few European bungalows, being the sea-side resort of Kuching; close by are large cutch works. In ancient days, judging by the large quantity of slag that is to be seen here, iron must have been extensively mined.

Recently some ancient and massive gold ornaments, seal rings, necklets, etc., were exposed by a landslip at the Limbang station, which have been pronounced to be of Hindu origin; and ancient Hindu gold ornaments have been found at Santubong and up the Sarawak river.

Bruni had been a powerful kingdom, and had conquered Luzon and the Sulu islands before it became a dependency of Majapahit, but at the time of the death of the last Batara49 of that kingdom, Bruni ceased to send tribute. The empire of Majapahit fell in 147850 before the Mussulman Malays. The origin of the Malays is shrouded in obscurity; they are first heard of in Sumatra, in Menangkabau,51 from whence they emigrated in A.D. 1160 to Singapura, "the Lion city." They were attacked and expelled in 1252 by the princes of Majapahit, when they settled in Malacca. There they throve, and embraced the religion of Islam in 1276.

From Sumatra and the Malay peninsula the Malays continued to spread, and gradually to establish sultanates and states under them. The process by which this was effected was seldom by conquest, but by the peaceful immigration of a few families who settled on some unoccupied part of the coast within the mouth of a river. Then, in the course of time, they increased and spread to neighbouring rivers, and formed a state. By subjecting the aboriginal tribes of the interior, and by compulsion or consent, including weaker Malayan states of like origin, by degrees some of these states expanded into powerful sultanates with feudal princes under them.

So the Malayan kingdoms arose and gained power; and strengthened by the spirit of cohesion which their religion gave them, they finally overthrew the Hindu-Javan empire of Majapahit.

In Borneo there were sultans at Bruni, Sambas, Banjermasin, Koti, Belungan, Pasir, Tanjong, Berau, and Pontianak, and other small states under pangirans and sherips.

Exaggerated accounts of the "sweet riches of Borneo" had led the early Portuguese, Dutch, and English voyagers to regard the island, the Insula Bonæ Fortunæ of Ptolemy, as the El Dorado of the Eastern Archipelago; but these in turn found out their error, and, directing their attention to the more profitable islands in its neighbourhood, almost forsook Borneo until later years.

The Spaniards appear to have been the first Europeans to visit the island, as they were the first to make the voyage round the world, and to find the way to the Archipelago from the east, a feat which caused the Portuguese much uneasiness. They touched at Bruni in 1521, and Pigafetta says that there were then 25,000 families in the city, which on a low computation would give the population at 100,000; and he gives a glowing account of its prosperity. The Portuguese, under the infamous Jorge de Menezes, followed in 1526, and they were there again in 1530. They confirm Pigafetta as to the flourishing condition of the place. From 1530 the Portuguese kept up a regular intercourse with Bruni from Malacca, which the great Alfonso d'Albuquerque had conquered in 1511, until they were expelled from that place by the Dutch in 1641. Then they diverted the trade, which was chiefly in pepper, to their settlement at Macao, where they had placed a Factory in 1557, and from whence a Roman Catholic mission was established at Bruni by Fr. Antonio di Ventimiglia, who died there in 1691. It seems certain they had a Factory at Bruni, probably for a short time only, in the seventeenth century, though it is impossible now to do more than conjecture the date; but that they continued their trade with Bruni up to the close of the eighteenth century appears to be without doubt; and also that they had a Factory at Sambas out of which they were driven by the Dutch in 1609. On Mercator's map, alluded to in the first footnote of this chapter, are the words "Lave donde foÿ Don Manuel de Lima," or Lave where Don Manuel of Lima52 resided. Lave is Mempawa, sometimes spelt Mempava in recent English maps, a place between Sambas and Pontianak – so the Portuguese were even farther south than Sambas in the sixteenth century.

In 1565, the Spanish took possession of the Philippines, conquered Manila in 1571, and, five years later, according to both Spanish and Bruni records, were taking an active interest in Bruni affairs, which, however, does not appear to have lasted for long. In 1576, Saif ul Rejal was Sultan. In the Bruni records53 it is stated that a noble named Buong Manis, whose title was Pangiran Sri Lela (Sirela in the Spanish records), was goaded into rebellion by the Sultan's brother, Rajah Sakam, by the abduction of his daughter on the day of her wedding. To gain a footing in Bruni the Spaniards took advantage of this, and Don Francisco La Sande, the second Governor of the Philippines, conquered Bruni, and set Sri Lela on the throne. Four years later the Spaniards again had occasion to support their protégé with an armed force; but it ended in the rightful Sultan being restored through the efforts of the Rajah Sakam, aided by a Portuguese, who had become a Bruni pangiran,54 and the usurper taking refuge in the Belait, where he was slain. To close the history, so far as it is known to us, of the Spanish connection with Bruni, in 1645, in retaliation for piracies committed on the coasts of their colonies, the Spanish sent an expeditionary force to punish Bruni, which it appears was very effectually done.

The first Dutchman to visit Bruni was Olivier Van Noort, in 1600. He seems to have been impressed by the politeness and civility of the Bruni nobles, but, fortunately for himself, not to the extent of trusting them too much, for treachery was attempted. Nine years later, as we have noticed, the Portuguese had to make room for the Dutch at Sambas, and here the latter established a Factory, which was, however, abandoned in 1623. They returned to this part of Borneo in 1778, and established Factories at Pontianak, Landak, Mempawa, and Sukadana, but these proving unprofitable were abandoned in 1791. In 1818, an armed force was sent to re-establish these Factories, two years after Java had been restored to Holland by England, and from these, including Sambas, the Dutch Residency of Western Borneo has arisen.

A certain Captain Cowley appears to have been the first Englishman, of whom we know anything, to visit Borneo, or at least that part of it with which this history deals, and in 1665 he spent some little time at "a small island which lay near the north end of Borneo,"55 but he did not visit the mainland; perhaps, however, he may not have been the first. As far back as 1612, Sir Henry Middleton projected a voyage to Borneo. He died at Bantam in Java, where the East India Company had established a Factory in 1603, but it was not until 1682 that the Dutch expelled the English from that place, and from thence to Borneo is too simple an adventure not to have been attempted and accomplished by the daring old sea-dogs of those days. According to Dampier, a Captain Bowry was in Borneo in 1686;56 some English were captured by the Dutch when they took Sukadana in 1687; and there were probably others there before, but no settlement on the north and north-western shores was effected by the English until 1773, when the East India Company formed a settlement at Balambangan, an island north of Marudu Bay, the same probably as that on which Captain Cowley had stayed. This settlement, however, was but short lived, for in February 1775 it was attacked by a small force of Sulus and Lanuns led by a cousin of the Sultan of Sulu, Datu Teting. The garrison of English and Bugis was more than sufficient to have repelled the attack, but they were taken completely by surprise; the Resident and the few settlers managed to escape in what vessels they could find.57 A number of cannon and muskets, and considerable booty, fell into the hands of the raiders. The motive for this act was revenge; the English had behaved badly to the natives of the neighbouring islands, and Datu Teting had himself suffered the indignity of being placed in the stocks when on a visit to the settlement. The Company had established a Factory at Bruni as well, having obtained from the Sultan the monopoly of the pepper trade, and to this Factory the survivors retired, but some settled on the island of Labuan, where they made a village. In 1803, the Company again established themselves at Balambangan, but after a short occupation abandoned the island, together with the Factory at Bruni. No punishment followed Datu Teting's act, and British prestige in northern Borneo was destroyed.

This is briefly the whole history of British enterprise in that part of Borneo lying north of the equator, and it reflects little credit on the part played by our countrymen in Eastern affairs in those days.

We have shown that Bruni early in the fourteenth century possessed a population of at least 100,000. According to Sir Hugh Low, two hundred years after Pigafetta's visit, the population was estimated at 40,000, with a Chinese population in its neighbourhood of 30,000, engaged in planting pepper.58 In 1809, the city had shrunk to 3000 houses with a population of 15,000.59 In 1847, Low placed the population at 12,000; the Chinese had then disappeared, excepting a few who had been reduced to slavery. The population, still diminishing, is now under 8000.

On the picturesque hills that surround the town are still to be found traces of thriving plantations which formerly existed there, and which extended for many miles into the interior. These have totally disappeared, with the population which cultivated them. In 1291, two centuries before the first European vessel rounded the Cape,60 Ser Marco Polo visited the Archipelago. He gives us the first narrative we possess of the Chinese junk trade to the westward, and mentions a great and profitable traffic carried on by the Chinese with Borneo,61 and this trade throve for many years afterwards; even in 1776 the commerce with China was considerable,62 though then it must have been declining, for it had ceased before the close of that century. Hunt records that in his time there were still to be seen at Bruni old docks capable of berthing vessels of from 500-600 tons. Now the most striking feature of the place is its profound poverty. Nothing remains of its past glory and prosperity but its ancient dynasty.

Sir Hugh Low tells us that these old Malay kingdoms appear to have risen to their zenith of power and prosperity two hundred years after their conversion to Islam, and then their decline commenced, but he should have added half a century to this epoch. The late Rajah was of opinion that perhaps the introduction of Muhammadanism may have been the cause of their deterioration. Two hundred and fifty years after the conversion of the Malays to Muhammadanism, and under the ægis of this religion, all the Malayan States attained their zenith. This period was coetaneous with the appearance of what may fairly be described as their white peril, and the introduction of Muhammadanism, a religion which Christians, in their ignorance of its true precepts, are too apt wholly to condemn, brought with it the pernicious sherips, the pests of the Archipelago. The decay of the old Malayan kingdoms was due primarily to the rapacious and oppressive policy adopted by Europeans in their early dealings with these States, which was continued in a more modified form until within recent times. How this was brought about, and how the sherips contributed to it, is in the sequel.

Prior to the advent of the late Rajah in 1838, Sarawak appears to have attracted no attention, except that Gonsavo Pereira, who made the second Portuguese visit to Bruni in 1530, says that Lave (Mempawa), Tanjapura (which cannot be identified), and Cerava (Sarawak) were the principal ports, and contained many wealthy merchants; and Valentyn relates that in 1609 the Dutch found that Calca (Kalaka), Saribas, and Melanugo had fallen away from Borneo (Bruni) and placed themselves under the power of the king of Johore.63 Melanugo is also difficult to identify, but it may be that a transcriptive error has crept in somewhere, and that it refers to the Malanau districts beyond Kalaka.64

The Sarawak Malays claim their origin from the ancient Kingdom of Menangkabau in Sumatra. Fifteen generations back, one Datu Undi, whose title was Rajah Jarom, a prince of the royal house of Menangkabau, emigrated with his people to Borneo, and settled on the Sarawak river. This prince had seven children, the eldest being a daughter, the Datu Permisuri.65 She married a royal prince of Java (this was after the downfall of Majapahit), and from them in a direct line came the Datu Patinggi Ali, of whom more will be noticed in the sequel, and the lineage is now represented by his grandson, the present Datu Bandar of Sarawak.

The Datu Permisuri remained in Sarawak. Rajah Jarom's eldest son established himself in the Saribas; his third son in the Samarahan; the fourth in the Rejang;66 and the fifth up the right-hand branch of the Sarawak, from whence his people spread into the Sadong. These settlements increased within their original limits, but were not extended beyond the Rejang.

Beyond this the Malays of Sarawak know little; but that these settlements must have early succumbed to the rising power of Bruni is evident. But it is also evident that after that power had commenced to wane, its hold over Sarawak gradually weakened until it became merely nominal. In 1609, the year they established themselves at Sambas, the Dutch found that these districts had fallen away from Bruni, as we have noticed. There may have been, and probably were, spasmodic assertions of authority on the part of Bruni, but it seems fairly evident that the Sarawak Malays managed to maintain an independence more or less complete for many years, up to within a very short period of the late Rajah's arrival, and then they had placed themselves again under the sovereignty of the Sultan, only to be almost immediately driven into rebellion by Pangiran Makota, the Sultan's first and last governor of Sarawak.

Just a century after the Portuguese had shown the way, and had won for their king the haughty title of "Lord of the Navigation and Commerce of Ethiopia, Arabia, Persia, and India," the English and the Dutch appeared in the Archipelago. The latter under Houtman, who had learnt the way from the Portuguese under whom he had served, were the first, in 1595, if we exclude Drake, 1578, and Cavendish, ten years later, and both merely passed through the southern portion of the Archipelago on their way home on their voyages round the world.

During the seventeenth century the English confined their energies to buccaneering and trading, and established only two Factories, at Bantam 1603, and at Bencoolen 1685. The Dutch went in for conquest, established themselves strongly at Jakatra, renamed by them Batavia, in 1611, and then proceeded to drive the Portuguese out of their settlements. The power of Portugal had been humbled by Spain, and the courageous spirit of the old conquistadores had departed. One by one her settlements were wrested from her, and by the end of the century Holland was paramount in the Archipelago. Beyond one or two abortive descents upon Luzon, one, probably the last, under the famous Tasman, the Dutch had left the Spaniards undisturbed in the Philippines, but to the English was left Bencoolen only, Bantam having been taken away from them in 1682, and to the Portuguese a portion of the island of Timor.

During the latter half of the eighteenth century commenced the rise of Great Britain as a political power in the Malayan Peninsula and Archipelago. In 1760, her only settlements, those on the western coast of Sumatra, had been destroyed by the French, but these were re-established in 1763, and Bencoolen was fortified. In 1786, the colony at Penang (Prince Edward's island) was established; and nine years later Malacca was captured from the Dutch.

Early in the nineteenth century came the temporary downfall of Holland. In 1811, Java was taken by the British, and the Dutch settlements and dependencies passed into their hands, though these were soon to be restored. After subjugating the independent princes of the interior and introducing order throughout Java, which the Dutch had so far failed to accomplish, all her possessions in the Archipelago were restored to Holland in 1816; and in 1825 Bencoolen was exchanged for Malacca. Singapore was founded in 1819.

In Borneo south of the equator, excepting Sukadana, which has already been mentioned, Banjermasin had been the only country to attract attention, and in this formerly rich pepper country the Dutch and English were alternately established. As early as 1606, the former, with disastrous results, attempted to establish a Factory there, and after that experience they appear to have left the place severely alone, and the Banjers were free of the white peril for another century. Then, in 1702, the East India Company established a Factory there. As this venture is an interesting illustration of the methods adopted by the English, and an example of their common misconduct and mismanagement, we give a few particulars. The old Dutch chronicler, Valentyn, tells us how the Factor, Captain Moor, who lived in a house constructed on a raft, with only a wretched earth rampart ashore, and a handful of English and Bugis (of the Celebes) soldiers, laid a heavy hand on the people, but managed to hold his own, until in 1706 a Captain Barry commenced building a proper fort, but he died before it was completed. Then a surgeon, who was more interested in natural history than anything else, became Factor. The aggression of the English increased, and the Sultan drove them out with the loss of many men and two ships. Captain Beeckman, of the H.E.I. Company's service, who was there in 1713, ascertained that Captain Barry had been poisoned, and he tells us so hateful had their servants rendered the name of the Company to the Banjereens that he had to pretend his ships were private traders. They had promised the Sultan to build no forts nor make soldiers. They grossly ill-treated, and even murdered the natives, imposed duties, and finally insulted the Sultan, and attempted to capture the queen-mother. The English, taken by the natives, including a Captain Cockburn, were put to a cruel death.67