Various

Notes and Queries, Number 65, January 25, 1851

NOTES

TRADITIONAL ENGLISH BALLADS

The task of gathering old traditionary song is surely a pleasant and a lightsome one. Albeit the harvest has been plentiful and the gleaners many, still a stray sheaf may occasionally be found worth the having. But we must be careful not to "pick up a straw."

One of your corespondents recommends, as an addition to the value of your pages, the careful getting together of those numerous traditional ballads that are still sometimes to be met with, floating about various parts of the country. This advice is by no means to be disregarded, but I wish to point out the necessity of the contributors to the undertaking knowing something about ballad literature. An acquaintance with the ordinary published collections, at least, cannot be dispensed with. Without this knowledge we should be only multiplying copies of worthless trifles, or reprinting ballads that had already appeared in print.

The traditional copies of old black-letter ballads are, in almost all cases (as may easily be seen by comparison), much the worse for wear. As a proof of this I refer the curious in these matters to a volume of Traditional Versions of Old Ballads, collected by Mr. Peter Buchan, and edited by Mr. Dixon for the Percy Society. The Rev. Mr. Dyce pronounces this "a volume of forgeries;" but, acquitting poor Buchan (of whom more anon) of any intention to deceive, it is, to say the least of it, a volume of rubbish; inasmuch as the ballads are all worthless modern versions of what had appeared "centuries ago" in their genuine shape. Had these ballads not existed in print, we should have been glad of them in any form; but, in the present case, the publication of such a book (more especially by a learned society) is a positive nuisance.

Another work which I cannot refrain from noticing, called by one of the reviewers "A valuable contribution to our stock of ballad literature"? is Mr. Frederick Sheldon's Minstrelsy of the English Border. The preface to this volume promises much, as may be seen by the following passage:—

"It is now upwards of forty years since Sir Walter Scott published his Border Minstrelsy, and during his 'raids,' as he facetiously termed his excursions of discovery in Liddesdale, Teviotdale, Tyndale, and the Merse, very few ballads of any note or originality could possibly escape his enthusiastic inquiry; for, to his love of ballad literature, he added the patience and research of a genuine antiquary. Yet, no doubt many ballads did escape, and still remain scattered up and down the country side, existing probably in the recollection of many a sun-browned shepherd, or the weather-beaten brains of ancient hinds, or 'eldern' women: or in the well-thumbed and nearly illegible leaves of some old book or pamphlet of songs, snugly resting on the 'pot-head,' or sharing their rest with the 'Great Ha' Bible,' Scott's Worthies, or Blind Harry's lines. The parish dominie or pastor of some obscure village, amid the many nooks and corners of the Borders, possesses, no doubt, treasures in the ballad-ware that would have gladdened the heart of a Ritson, a Percy, or a Surtees; in the libraries, too, of many an ancient descendant of a Border family, some black-lettered volume of ballads, doubtlessly slumbers in hallowed and unbroken dust."

This reads invitingly; the writer then proceeds:—

"From such sources I have obtained may of the ballads in the present collection. Those to which I have stood godfather, and so baptized and remodelled, I have mostly met with in the 'broad-side' ballads, as they are called."

Although the writer here speaks of Ritson and Percy as if he were acquainted with their works, it is very evident that he had not looked into their contents. The name of Evans' Collection had probably never reached him. Alas! we look in vain for the tantalising "pamphlet of songs,"—still, perhaps, snugly resting on the "pot-head," where our author in his "poetical dream" first saw it. The "black-lettered volume of ballads" too, in the library of the "ancient descendant of a Border family," still remains in its dusty repository, untouched by the hand of Frederick Sheldon.

In support of the object of this paper I shall now point out "a few" of the errors of The Minstrelsy of the English Border.

P. 201. The Fair Flower of Northumberland:—

"It was a knight in Scotland born,

Follow my love, come over the Strand;

Was taken prisoner, and left forlorn

Even by the good Erle Northumberland."

This is a corrupt version of Thomas Deloney's celebrated ballad of "The Ungrateful Knight," printed in the History of Jack of Newbery, 1596, and in Ritson's Ancient Songs, 1790. A Scottish version may be found in Kinloch's Ballads, under the title of the "The Provost's Daughter." Mr. Sheldon knows nothing of this, but says,—

"This ballad has been known about the English Border for many years, and I can remember a version of it being sung by my grandmother!"

He also informs us that he has added the last verse but one, in order to make the "ends of justice" more complete!

P. 232. The Laird of Roslin's Daughter:—

"The Laird of Roslin's daughter

Walk'd through the wood her lane;

And by her came Captain Wedderburn,

A servant to the Queen."

This is a wretched version (about half the original length) of a well-known ballad, entitled "Captain Wedderburn's Courtship." It first appeared in print in The New British Songster, a collection published at Falkirk, in 1785. It was afterwards inserted in Jamieson's Popular Ballads and Songs, 1806; Kinloch's Ancient Ballads, 1826; Chambers' Scottish Ballads, 1829, &c. But hear what Mr. Sheldon has to say, in 1847:—

"This is a fragment of an apparently ancient ballad, related to me by a lady of Berwick-on-Tweed, who used to sing it in her childhood. I have given all that she was able to furnish me with. The same lady assures me that she never remembers having seen it in print [!!], and that she had learnt if from her nurse, together with the ballad of 'Sir Patrick Spens,' and several Irish legends, since forgotten."

P. 274. The Merchant's Garland:—

"Syr Carnegie's gane owre the sea,

And's plowing thro' the main,

And now must make a lang voyage,

The red gold for to gain."

This is evidently one of those ballads which calls Mr. Sheldon "godfather." The original ballad, which has been "baptized and remodelled," is called "The Factor's Garland." It begins in the following homely manner:—

"Behold here's a ditty, 'tis true and no jest

Concerning a young gentleman in the East,

Who by his great gaming came to poverty,

And afterwards went many voyages to sea."

P. 329. The rare Ballad of Johnnie Faa:—

"There were seven gipsies in a gang,

They were both brisk and bonny O;

They rode till they came to the Earl of Castle's house,

And here they sang so sweetly O."

This is a very hobbling version (from the recitation of a "gipsy vagabond") of a ballad frequently reprinted. It first appeared in Ramsay's Tea-Table Miscellany; afterwards in Finlay's and Chambers' Collections. None of these versions were known to Mr. Sheldon.

I have now extracted enough from the Minstrelsy of the English Border to show the mode of "ballad editing" as pursued by Mr. Sheldon. The instances are sufficient to strengthen my position.

One of the most popular traditional ballads still floating about the country, is "King Henrie the Fifth's Conquest:"—

"As our King lay musing on his bed,

He bethought himself upon a time,

Of a tribute that was due from France,

Had not been paid for so long a time."

It was first printed from "oral communication," by Sir Harris Nicolas, who inserted two versions in the Appendix to his History of the Battle of Agincourt, 2d edition, 8vo. 1832. It again appeared (not from either of Sir Harris Nicolas's copies) in the Rev. J.C. Tyler's Henry of Monmouth, 8vo. vol. ii. p. 197. And, lastly, in Mr. Dixon's Ancient Poems, Ballads, and Songs of the Peasantry of England, printed by the Percy Society in 1846. These copies vary considerably from each other, which cannot be wondered at, when we find that they were obtained from independent sources. Mr. Tyler does not allude to Sir Harris Nicolas's copies, nor does Mr. Dixon seem aware that any printed version of the traditional ballad had preceded his. The ballad, however, existed in a printed "broad-side" long before the publications alluded to, and a copy, "Printed and sold in Aldermary Church Yard," is now before me. It is called "King Henry V., his Conquest of France in Revenge for the Affront offered by the French King in sending him (instead of the Tribute) a ton of Tennis Balls."

An instance of the various changes and mutations to which, in the course of ages, a popular ballad is subject, exists in the "Frog's Wedding." The pages of the "NOTES AND QUERIES" testify to this in a remarkable degree. But no one has yet hit upon the original ballad; unless, indeed, the following be it, and I think it has every appearance of being the identical ballad licensed to Edward White in 1580-1. It is taken from a rare musical volume in my library, entitled Melismata; Musicall Phansies, fitting the Court, Citie, and Countrey Humours. Printed by William Stansby for Thomas Adams, 1611. 4to.

"THE MARRIAGE OF THE FROGGE AND THE MOUSE

"It was the Frogge in the well,

Humble-dum, humble dum;

And the merrie Mouse in the mill,

Tweedle, tweedle twino.

"The Frogge would a-wooing ride,

Humble-dum, &c.

Sword and buckler by his side,

Tweedle, &c.

"When he was upon his high horse set,

Humble-dum, &c.

His boots they shone as blacke as jet.

Tweedle, &c.

"When he came to the merry mill pin,

Humble-dum, &c.

Lady Mouse, beene you within?

Tweedle, &c.

"Then came out the dusty Mouse,

Humble-dum, &c.

I am Lady of this house,

Tweedle, &c.

"Hast thou any minde of me?

Humble-dum, &c.

I have e'ne great minde of thee,

Tweedle, &c.

"Who shall this marriage make?

Humble-dum, &c.

Our Lord, which is the Rat,

Tweedle, &c.

"What shall we have to our supper?

Humble-dum, &c.

Three beanes in a pound of butter,

Tweedle, &c.

"When supper they were at,

Humble-dum, &c.

The frogge, the Mouse, and even the Rat,

Tweedle, &c.

"Then came in Gib our Cat,

Humble-dum, &c.

And catcht the Mouse even by the backe,

Tweedle, &c.

"Then did they separate,

Humble-dum, &c.

And the Frogge leapt on the floore so flat,

Tweedle, &c.

"Then came in Dicke our Drake,

Humble-dum, &c.

And drew the Frogge even to the lake,

Tweedle, &c.

"The Rat ran up the wall,

Humble-dum, &c

A goodly company, the Divell goe with all,

Tweedle, &c."

From what I have shown, the reader will agree with me, that a collector of ballads from oral tradition should possess some acquaintance with the labours of his predecessors. This knowledge is surely the smallest part of the duties of an editor.

I remember reading, some years ago, in the writings of old Zarlino (an Italian author of the sixteenth century), an amusing chapter on the necessary qualifications for a "complete musician." The recollection of this forcibly returns to me after perusing the following extract from the preface to a Collection of Ballads (2 vols. 8vo. Edinburgh, 1828), by our "simple" but well-meaning friend, "Mr. Peter Buchan of Peterhead."

"No one has yet conceived, nor has it entered the mind of man, what patience, perseverance, and general knowledge are necessary for an editor of a Collection of Ancient Ballads; nor what mountains of difficulties he has to overcome; what hosts of enemies he has to encounter; and what myriads of little-minded quibblers he has to silence. The writing of explanatory notes is like no other species of literature. History throws little light upon their origin [the ballads, I suppose?], or the cause which gave rise to their composition. He has to grope his way in the dark: like Bunyan's pilgrim, on crossing the Valley of the Shadow of Death, he hears sounds and noises, but cannot, to a certainty, tell from whence they come, nor to what place they proceed. The one time, he has to treat of fabulous ballads in the most romantic shape; the next, legendary, with all its exploded, obsolete, and forgotten superstitions; also history, tragedy, comedy, love, war, and so on; all, perhaps, within the narrow compass of a few hours,—so varied must his genius and talents be."

After this we ought surely to rejoice, that any one hardy enough to become an Editor of Old Ballads is left amongst us.

EDWARD F. RIMBAULT.

THE FATHER OF PHILIP MASSINGER

Gifford was quite right in stating that the name of the father of Massinger, the dramatist, was Arthur, according to Oldys, and not Philip, according to Wood and Davies. Arthur Massinger (as he himself spelt the name, although others have spelt it Messenger, from its supposed etymology) was in the service of the Earl of Pembroke, who married the sister of Sir Philip Sidney, in whose family the poet Daniel was at one time tutor. I have before me several letters from him to persons of note and consequence, all signed "Arthur Massinger;" and to show his importance in the family to which he was attached, I need only mention, that in 1597, when a match was proposed between the son of Lord Pembroke and the daughter of Lord Burghley, Massinger, the poet's father, was the confidential agent employed between the parties. My purpose at present is to advert to a matter which occurred ten years earlier, and to which the note I am about to transcribe relates. It appears that in March, 1587, Arthur Massinger was a suitor for the reversion of the office of Examiner in the Court of the Marches toward South Wales, for which also a person of the name of Fox was a candidate; and, in order to forward the wishes of his dependent, the Earl of Pembroke wrote to Lord Burghley as follows:—

"My servant Massinger hathe besought me to ayde him in obteyning a reversion from her Majestie of the Examiner's office in this courte; whereunto, as I willingly have yielded, soe I resolved to leave the craving of your Lordship's furtheraunce to his owne humble sute; but because I heare a sonn of Mr. Fox (her Majestie's Secretary here) doth make sute for the same, and for the Mr. Sherar, who now enjoyethe it, is sicklie, I am boulde to desier your Lordship's honorable favour to my servaunte, which I shall most kindlie accepte, and he for the same ever rest bounde to praye for your Lordship. And thus, leaving further to trouble you, &c. 28. March, 1587. H. PEMBROKE."

The whole body of this communication, it is worth remark, is in the handwriting of Arthur Massinger (whose penmanship was not unlike that of his son), and the signature only that of the Earl, in whose family he was entertained. I have not been able to ascertain whether the application was successful; and it is possible that some of the records of the court may exist, showing either the death of Sherar, and by whom he was succeeded about that date, or that Sherar recovered from his illness. As I have before said, it is quite clear that Arthur Massinger was high in the confidence and service of Lord Pembroke ten years after the date of the preceding note.

I have a good deal more to say about Arthur Massinger, but I must take another time for the purpose.

THE HERMIT OF HOLYPORT.

TOUCHSTONE'S DIAL

(Vol. ii., p. 405.)

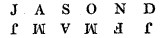

The conjecture of Mr. Knight, in his note to As You Like It, and to which your correspondent J.M.B. has so instructively drawn our attention, is undoubtedly correct. The "sun-ring" or ring-dial, was probably the watch of our forefathers some thousand years previous to the invention of the modern chronometer, and its history is deserving of more attention than has hitherto been paid to it. Its immense antiquity in Europe is proved by its still existing in the remotest and least civilised districts of North England, Scotland, and the Western Isles, Ireland, and in Scandinavia. I have in my possession two such rings, both of brass. The one, nearly half an inch broad, and two inches in diameter, is from the Swedish island of Gothland, and is of more modern make. It is held by the finger and thumb clasping a small brass ear or handle, to the right of which a slit in the ring extends nearly one-third of the whole length. A small narrow band of brass (about one-fifth of the width) runs along the centre of the ring, and of course covers the slit. This narrow band is movable, and has a hole in one part through which the rays of the sun can fall. On each side of the band (to the right of the handle) letters, which stand for the names of the months, are inscribed on the ring as follows:—

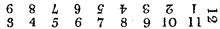

Inside the ring, opposite to these letters, are the following figures for the hours:—

The small brass band was made movable that the ring-click might be properly set by the sun at stated periods, perhaps once a month.

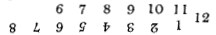

The second sun-ring, which I bought in Stockholm in 1847, also "out of a deal of old iron," is smaller and much broader than the first, and is perhaps a hundred years older; it is also more ornamented. Otherwise its fashion is the same, the only difference being in the arrangement of the inside figures, which are as follows:—

The ring recovered by Mr. Knight evidently agrees with the above. I hope Mr. K. will, sooner or later, present the curiosity to our national museum,—which will be driven at last, if not by higher motives, by the mere force of public opinion and public indignation, to form a regularly arranged and grand collection of our own British antiquities in every branch, secular and religious, from the earliest times, down through the middle ages, to nearly our own days. Such an archæological department could count not only upon the assistance of the state, but upon rich and generous contributions from British sources, individuals and private societies, at home and abroad, as well as foreign help, at least in the way of exchange. But any such plan must be speedily and well organised and well announced!

I give the above details, not only because they relate to a passage in our immortal bard, who has ennobled and perpetuated every word and fact in his writings, but because they illustrate the astronomical antiquities of our own country and our kindred tribes during many centuries. These sun-dials are now very scarce, even in the high Scandinavian North, driven out as they have been by the watch, in the same manner as the ancient clog1 or Rune-staff (the carved wooden perpetual almanac) has been extirpated by the printed calendar, and now only exists in the cabinets of the curious. In fifty years more sun-rings will probably be quite extinct throughout Europe. I hope this will cause you to excuse my prolixity. Will no astronomer among your readers direct his attention to this subject? Does anything of the kind still linger in the East?

GEORGE STEPHENS.

Stockholm.

DISCREPANCIES IN DUGDALE'S ACCOUNT OF SIR RALPH DE COBHAM

There are some difficulties in Dugdale's account of the Cobham family which it may be well to bring before your readers; especially as several other historians and genealogists have repeated Dugdale's account without remarking on its inconsistencies. In speaking of a junior branch of the family, he says, in vol. ii. p. 69., "There was also Ralphe de Cobham, brother of the first-mentioned Stephen." He only mentions one Stephen but names him twice, first at page 66., and again at 69. Perhaps he meant the above-mentioned Stephen. He continues:—

"This Ralphe took to wife Mary Countess of Norfolk, widdow of Thomas of Brotherton. Which Mary was Daughter to William Lord Ros, and first married to William Lord Braose of Brembre; and by her had Issue John, who 20 E. III., making proof of his age, and doing his Fealty, had Livery of his lands."

At page 64. of the same volume he states that Thomas de Brotherton died in 12 Edward III., which would be only eight years before his widow's son, by a subsequent husband, is said to have become of age. That he did become of age in this year we have unquestionable evidence. In Cal. Ing. P. Mortem, vol. iv. p. 444., we find this entry:—

"Anno 20 Edw. III. Johannes de Cobham, Filius et Hæres Radulphi de Cobeham defuncti. Probatio ætatis."

There is also abundant proof that Thomas de Brotherton died in 12 Edward III. The most natural way of removing this difficulty would be to conclude that John de Cobham was the son of Ralph by a previous marriage. But here we have another difficulty to encounter. He is not only called the son of Mary, Countess of Norfolk, or Marishall, by Dugdale, but in all contemporaneous records. See Rymer's Foed., vol. vi. p. 136.; Rot. Orig., vol. ii. p. 277.; Cal. Rot. Pat., p. 178., again at p. 179.; Cal. Ing. P. Mortem, vol. iii. pp. 7. 10. Being the son-in-law of the Countess, he was probably called her son to distinguish him from a kinsman of the same name, or because of her superior rank. She is frequently styled the widow, and sometimes the wife of Thomas de Brotherton, even after the death of her subsequent husband, Sir Ralph de Cobham. In the escheat at her death she is thus described:—

"Maria Comitissa Norfolc', uxor Thome de Brotherton, Comitis Norfolc', Relicta Radi de Cobeham, Militis."

It is remarkable that this discrepancy in Sir John Cobham's age, and the time of his supposed mother's marriage with his father, has never before, as far as my knowledge extends, been noticed by any of the numerous writers who have repeated Dugdale's account of this family.

Before concluding I will mention another mistake respecting the Countess which runs through most of our county histories where she is named. For a short period she became an inmate of the Abbey of Langley, and is generally stated to have entered it previously to her marriage with Sir Ralph de Cobham. Clutterbuck, in his History of Hertfordshire (vol. ii. p. 512.), for instance, relates the circumstance in these words:—

"In the 19th year of the reign of Edward III., she became a nun in the Abbey of Langley, in the country of Norfolk; but quitting that religious establishment, she married Sir Ralph Cobham, Knt., and died anno 36 Edward III."

By Cal. Ing. P. Mortem, vol. i. p. 328., we find that Ralph Cobham died 19th Edward III.2, that is, the same year in which the Countess entered the Abbey, from whence we may conclude that she retired there to pass in seclusion the period of mourning.

W. HASTINGS KELKE.