Various

Notes and Queries, Number 31, June 1, 1850

OUR SECOND VOLUME

We cannot resist the opportunity which the commencement of our Second Volume affords us, of addressing a few words of acknowledgment to our friends, both contributors and readers. In the short space of seven months, we have been enabled by their support to win for "NOTES AND QUERIES" no unimportant position among the literary journals of this country. We came forward for the purpose of affording the literary brotherhood of this great nation an organ through which they might announce their difficulties and requirements, through which such difficulties might find solution, and such requirements be supplied. The little band of kind friends who first rallied round us has been reinforced by a host of earnest men, who, at once recognising the utility of our purpose, and seeing in our growing prosperity how much love of letters existed among us, have joined us heart and hand in the great object we proposed to ourselves in our Prospectus; namely, that of making "NOTES AND QUERIES" by mutual intercommunication, "a most useful supplement to works already in existence—a treasury for enriching future editions of them—and an important contribution towards a more perfect history than we yet possess of our language, our literature, and those to whom we owe them."

Thanks, again and again, to the friends and correspondents, who, by their labours, are enabling us to accomplish this great end. To them be the honour of the work. We are content to say with the Arabian poet:

"With conscious pride we view the band

Of faithful friends that round us stand;

With pride exult, that we alone

Can join these scattered gems in one;

Rejoiced to be the silken line

On which these pearls united shine."

NOTES

PARISH REGISTERS.—STATISTICS

Among the good services rendered to the public by yourself and your correspondents, few, I think will be found more important than that of having drawn their attention to Mr. Wyatt Edgell's valuable suggestions on the transcription of Parochial Registers. The supposed impracticability of his plan has perhaps hitherto deterred those most competent to the work from giving it the consideration which it deserves. I believe the scheme to be perfectly practicable; and, as a first move in the work, I send you the result of my own dealings with the registers of my parish.

It is many years since I felt the desideratum which Mr. Edgell has brought before the public; and, by way of testing the practicability of transcribing, and printing the parochial registers of the entire kingdom in a form convenient for reference, I made an alphabetical transcript of my own, which is now complete. The modus operandi which I adopted was this:—1. I first transcribed, on separate slips of paper, each baptismal entry, with its date, and a reference to the page of the register, tying up the slips in the order in which the names were entered in the register; noting, as I proceeded, on another paper, the number of males and females in each year.

2. The slips being thus arranged, they came in their places handy for collation with the original. I then collated each, year by year; during the process depositing the slips one by one in piles alphabetically, according to the initial letter of the surnames.

3. This done, I sorted each pile in an order as strictly alphabetical as that used in dictionaries or ordinary indices.

4. I then transcribed them into a book, in their order, collating each page as the work proceeded.

5. I then took the marriages in hand, adopting the same plan; entering each of these twice, viz. both under the husband's and the wife's name.

6. Next, the burials, on the same plan.

7. I then drew up statistical tables of the number of baptisms, marriages, and burials in each year, males and females separately where the register appeared badly kept, making notes of the fact, and adding such observations as occasionally seemed necessary.

8. I then drew up lists of vicars, transcripts of miscellaneous records of events, and other casual entries that appeared in the register.1

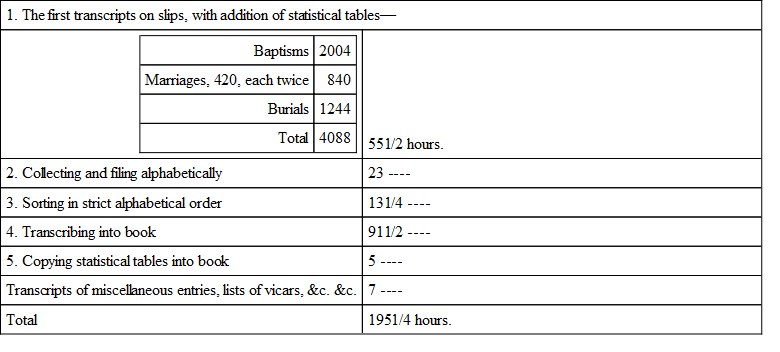

I noted, as I went on, the time occupied in each of these operations. It was as follows:—

My registers begin in the year 1558, and the present population of the parish is about 420, so that you have here an account of the labour necessary to complete an alphabetical transcript of the register of a rural parish of that extent in population.

I send you the result as a first step to a work of great national importance, and of inestimable value with relation to family descent, title to property long in abeyance, &c. &c. As to statistics, I doubt whether any data worthy of consideration can be obtained from these sources, owing to the constant irregularities which occur in keeping the registers.

No man, much less the minister of a parish, who has abundant calls upon his time, can be expected to sit down to the task of transcribing his registers through many consecutive hours; but there are few who could not give occasionally one or two hours to the work. In this way I effected my transcripts; the work of 195 hours being distributed through nearly five months—no great labour after all.

On an average, twelve words, with the figures, may be calculated for each entry, which will give for this parish about 500 folios. Each entry having been transcribed twice, we may call it, at a rough calculation, 1000 folios written out ready for printing.

If the authorities at the Registrar-General's office would give their attention to it, they must have there abundant data on which to form calculations as to the probable cost of the undertaking And I cannot help thinking that, setting aside printing as an after consideration, alphabetical transcripts, at least, might be obtained of all the parochial registers in the kingdom, and deposited in that office, at no insurmountable expense; and if the cost appear too heavy, the accomplishment of the work might be distributed through a given number of years; say ten, or even twenty.

Parliament might, perhaps, be induced to vote an annual grant for so important a work till it was accomplished; albeit, when we think of their niggardly denial of any thing to the printing, or even the conservation of the public records, sanguine hopes from that quarter can hardly be indulged.

To insure correctness, without which the scheme would be utterly valueless, I would propose that a certain number of competent transcribers be appointed for each county, either at a given salary, or at a remuneration of so much per entry, to copy the registers of those parishes the ministers of which are unwilling to do it, or feel themselves unequal to the task. The option, however, should always, in the first instance, be given to the minister, as the natural custos of the registers, and as one, from local knowledge, likely to do the work correctly. To each county there should also be appointed one or more competent persons as collators, to correct the errors of the transcribers.

I throw out these rough hints in the hope that some of your correspondents will furnish their ideas on the subject, till we at last arrive at a fully practicable plan of carrying out Mr. Wyatt Edgell's suggestions, and, at all events, obtain transcripts, if not printed copies, of every register in the kingdom.

L.B.L.

THE HUDIBRASTIC VERSE

"He that fights and runs away," &c.—Your correspondent MELANION may be assured that the orations of Demosthenes do not afford any trace of the proverbial senarius, ανηρ δ φευγων και παλιν μαχησεται; and it does not appear quite clear how the apophthegm containing it (which has been so generally attributed to Plutarch) has been concocted. Heeren, in doing full justice to the biographical talent of the Chæronean, has yet observed, "We may easily see that in his Lives he only occasionally indicates his authorities, because his own head was so often the source." It is in the life of Demosthenes that the story of his flight is told, but briefly; and for that part which relates to the inscription on the shield of Demosthenes, he says, 'ως ελεγε Πυθεας. The other life among those of the Ten Orators, the best critics think not to be Plutarch's; and the relation in it is too ridiculous for credit; yet it is repeated by Photius.

The first writer in which the story takes something of the form in which Erasmus gives it is Aulus Gellius (Noct. Att. l. xvii. c. 21.):—

"Post inde aliquanto tempore Philippus apud Chaeroneam proelio magno Athenienses vicit. Tum Demosthenes orator ex eo proelio salutem fuga quaesivit: quumque id ei, quod fugerat, probrose objiceretur; versu illo notissimo elusit, ανηρ δ φευγων, inquit, και παλιν μαχησεται."

We here see that the senarius is designated as a well-known verse, so that it must have been in the mouths of the people long before it was applied to this piece of gossip. I have hitherto not been able to trace it to an earlier writer.

The Apophthegmata of Erasmus were first published, I believe, in 1531, in six books. I have an edition printed by Frobenius, at Basle, in 1538, in which two more books are added; and, in an epistle prefixed to the seventh book, Erasmus says,—

"Prodiit opus, tanta aviditate distractum est, ut protinus à typographo coeperit efflagitare denuo."

He names twenty-one ancient Greek and Latin authors from which the apophthegms had been collected; and, with regard to what he has taken from Plutarch, he mentions the licence he has used:—

"Nos Plutarchum multis de causis sequi maluimus quam interpretari, explanare quam vertere."

It is from this book of Erasmus that the worthy Nicolas Udall selected his Two Bookes of Apophthegmes; and he tells his readers,—

"I have been so bold with mine author as to make the first booke and second booke, which he maketh third and fowerth."

Udall has occasionally added further explanations of his own to those translated from Erasmus. He promises, in good time, the remaining, books, but says,—

"I have thought better, with two of the eight, to minister unto you a taste of this bothe delectable and fruitefull recreation."

Those who are desirous of knowing at large the course pursued by Erasmus in the compilation of this amusing and once popular work, will find it fully stated in his preface; one passage of which will show the large licence he allowed himself:—

"Sed totum opus quodammodo meum feci, dum et explanatius effero qua Graece referuntur, interjectis interdum quæ apud alios autores additur comperissem," &c.

The only sure ground, as far as I can discover, for this gradually constructed legend, is the mention of the flight of Demosthenes by Æschines and Dinarchus. In the more amplified editions of Erasmus's Adages, after the publication of the Apophthegmata, he repeats the story in illustration of a Latin proverb (probably only a version of the Greek), "Vir fugiens et denuo pugnabitur;" and I find in some collections of the sixteenth century both the Latin and Greek given upon the authority of Plutarch! Langius, in his Polyanthea (a copious common-place book which would outweigh twenty of our late Laureate's) has given the apophthegm verbatim from Erasmus, and has boldly appended Plutarch's name. But the more extraordinary course is that which one Gualandi took, who published, at Venice, in 1568, in 4to., an omnium gatherum, in five books, from various sources, in which there is much taken from Erasmus, and yet the title is Apoftemmi di Plutarco. In this book, the whole of the twenty-three apophthegms of Erasmus which relate to Demosthenes are given, and two more added at the end. It appears that Philelphus, and after him Raphael Regius, had printed, in the fifteenth century, Latin collections under the title of Plutarch's Apophthegms, and, according to Erasmus, had both taken liberties with their original. I have not seen either of these Latin versions, of which there were several editions. As far as regards Demosthenes, I think we may fairly conclude that the story is apocryphal. The Greek proverbial verse was no doubt a popular saying, which Aulus Gellius thought might give a lively turn to his story, of which an Italian would say, "Se non vero è ben trovato."

S.W. SINGER.

Feb. 9. 1850.