Various

Notes and Queries, Number 29, May 18, 1850

OLIVER CROMWELL AS A FEOFFEE OF PARSON'S CHARITY, ELY

There is in Ely, where Cromwell for some years resided, an extensive charity known as Parson's Charity, of which he was a feoffee or governor. The following paper, which was submitted to Mr. Carlyle for the second or third edition of his work, contains all the references to the great Protector which are to be found in the papers now in the possession of the trustees. The appointment of Oliver Cromwell as a feoffee does not appear in any of the documents now remaining with the governors of the charity. The records of the proceedings if the feoffees of his time consist only of the collector's yearly accounts of monies received and expended, and do not show the appointments of the feoffees. These accounts were laid before the feoffees from time to time, and signed by them in testimony of their allowance.

Cromwell's name might therefore be expected to be found at the foot of some of them; but it unfortunately happens that, from the year 1622 to the year 1641, there is an hiatus in the accounts. At the end of Book No. 1., between forty and fifty leaves have been cut away, and at the commencement of Book no. 2. about twelve leaves more. Whether some collector of curiosities has purloined these leaves for the sale of any autographs of Cromwell contained in them, or whether their removal may be accounted for by the questions which arose at the latter end of the above period as to the application of the funds of the charity, cannot now be ascertained.

There are however, still in the possession of the governors of the charity, several documents which clearly show that from the year 1635 to the year 1641 Cromwell was a feoffee or governor, and took an active part in the management of the affairs of the charity. There is an original bond, dated the 30th of May, 1638, from one Robert Newborne to "Daniell Wigmore, Archdeacon of Ely, Oliver Cromwell, Esq., and the rest of the Corporation of Ely." The feoffees had then been incorporated by royal charter, under the title of "The Governors of the Lands and Possessions of the Poor of the City or Town of Ely."

There are some detached collectors' accounts extending over a portion of the interval between 1622 and 1641, and indorsed, "The Accoumpts of Mr. John Hand and Mr. William Cranford, Collectors of the Revenewes belonging to the Towne of Ely."

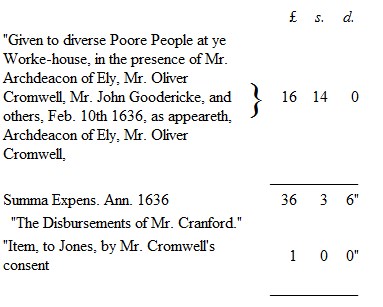

The following entries are extracted from these accounts:—

"The Disbursements of Mr. John Hand from the of August 1636 unto the of 1641."

"Anno 1636."

After several other items,—

Mr. Cranford's disbursements show no dates. His receipts immediately followed Mr. Hand's in point of dates.

About the year 1639 a petition was filed in the Court of Chancery by one Thomas Fowler, on behalf of himself and others, inhabitants of Ely, against the feoffees of Parson's Charity, and a commission for charitable uses was issued. The commissioners sat at Ely, on the 25th of January, 1641, and at Cambridge on the 3rd of March in the same year, when several of the feoffees with other persons were examined.

At the conclusion of the joint deposition of John Hand and William Cranford, two of the feoffees, is the following statement:—

"And as to the Profitts of the said Lands in theire tyme receaved, they never disposed of any parte thereof but by the direction and appointment of Mr. Daniell Wigmore, Archdeacon of Ely, Mr. William March, and Mr. Oliver Cromwell."

"These last two names were inserted att Camb. 8 Mar. 1641, by Mr. Hy. C."

The last name in the above note is illegible, and the last two names in the deposition are of a different ink and handwriting from the preceding part, but of the same ink and writing as the note.

An original summons to the feoffees, signed by the commissioners, is preserved. It requires them to appear before the commissioners at the Dolphin Inn, in Ely, on the 25th of the then instant January, to produce before the commissioners a true account "of the monies, fines, rents, and profits by you and every of you and your predecessors feoffees receaved out of the lands given by one Parsons for the benefitt of the inhabitants of Ely for 16 years past," &c. The summons is dated at Cambridge, the 13th of January, 1641, and is signed by the three commissioners,

"Tho. Symon.

Tho. Duckett.

Dudley Page."

The summons is addressed

"To Matthew, Lord Bishop of Ely,

Willm. Fuller, Deane of Ely, and to

Daniell Wigmore, Archdeacon of Ely.

William March, Esq.

Anthony Page, Esq.

Henry Gooderick, Gent.

Oliver Cromwell, Esq.

Willm. Anger.

Willm. Cranford.

John Hand, and

Willm. Austen."

Whether Cromwell attended the sitting of the commissioners does not appear.

The letter from Cromwell to Mr. John Hand, published in Cromwell's _Memoirs of Cromwell_, has not been in the possession of the feoffees for some years.

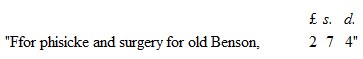

There is, however, an item in Mr. Hand's disbursements, which probably refers to the person mentioned in that letter. It is as follows:—

Cromwell's letter appears to be at a later date than this item.

John Hand was a feoffee for many years, and during his time executed, as was usual, the office of collector or treasurer. It may be gathered from the documents preserved that Cromwell never executed that office. The office was usually taken by the feoffees in turn then, as at the present time; but Cromwell most probably was called to a higher sphere of action before his turn arrived.

It is worthy of note, that Cromwell's fellow-trustees, the Bishop of Ely (who was the celebrated Matthew Wren), Fuller the Dean, and Wigmore the Archdeacon, were all severely handled during the Rebellion.

ARUN.

DR. SAM. PARR AND DR. JOHN TAYLOR, OF SHREWSBURY AND SHREWSBURY SCHOOL

Looking at the Index to the _Memoirs of Gilbert Wakefield_, edit. of 1804, I saw, under the letter T., the following entries:—

"Taylor, Rev. Dr. John, Tutor of Warrington Academy, i. 226.

–– his latinity, why faulty, ii. 449."

But I instantly suspected an error: for it was my belief that those two notices were designed for two distinct scholars. Accordingly, I revised both passages, and found that I was right in my conjecture. The facts are these:—In the former of the references, "The Rev. John Taylor, D.D.," is pointed out. The other individual, of the same name, was John Taylor, LL.D., a native of Shrewsbury, and a pupil of Shrewsbury School: HIS latinity it is which Dr. Samuel Parr [ut supr.] characterises as FAULTY: and for the defects of which he endeavours, successfully or otherwise, to account. So that whosoever framed the Index has here committed an oversight.

In the quotation which I proceed to make, Parr is assigning causes of what, as I think, he truly deemed blemishes in G. Wakefield's Latin style; and this is the language of the not unfriendly censor:—

"—None, I fear, of his [W.'s] Latin productions are wholly free from faults, which he would have been taught to avoid in our best public seminaries, and of which I have seen many glaring instances in the works of Archbishop Potter, Dr. John Taylor, Mr. Toup, and several eminent scholars now living, who were brought up in private schools."

But could Parr mean to rank Shrewsbury School among the "private schools?" I am not old enough to recollect what it was in the times of Taylor, J., the civilian, and the editor of Demosthenes. Its celebrity, however, in our own day, and through a long term of preceding years, is confessed. Dr. Parr's judgement in this case might be somewhat influenced by his prepossessions as an Harrovian.

N.

April, 1850.

PROVINCIAL WORDS

In Twelfth Night, Act ii. Scene 3., occur the words "Sneck up," in C. Knight's edition, or "Snick up," Mr. Collier's edition. These words appear most unaccountably to have puzzled the commentators. Sir Toby Belch uses them in reply to Malvolio, as,—

Enter MALVOLIO

"Mal. My masters, are you mad? or what are you? Have you no wit, manners, nor honesty, but to gabble like tinkers at this time of night? Do you make an alehouse of my lady's house, that you squeak out your cozier's catches without any mitigation or remorse of voice? Is there no respect of place, person, nor time, in you?

"Sir To. We did keep time, Sir, in our catches. Sneck up!"

"Sneck up," according to Mr. C. Knight, is explained thus:—

"A passage in Taylor, the Water Poet, would show that this means 'hang yourself.' A verse from his 'Praise of Hempseed' is given in illustration."

"Snick up," according to Mr. Collier, is said to be "a term of contempt," of which the precise meaning seems to have been lost. Various illustrations are given, as see his Note; but all are wide of the meaning.

Turn to Halliwell's Dictionary of Archaic and Provincial Words, 2d edition, and there is this explanation:—

"SNECK, that part of the iron fastening of a door which is raised by moving the latch. To sneck a door, is to latch it."

See also Burn's Poems: The Vision, Duan First, 7th verse, which is as follows:—

"When dick! the string the snick did draw,—

And jee! the door gaed to the wa';

An' by my ingle-lowe I saw,

Now bliezin' bright,

A tight, outlandish Hizzie, braw,

Come full in sight."

These quotations will clearly show that "sneck" or "snick" applies to a door; and that to sneck a door is to shut it. I think, therefore, that Sir Toby meant to say in the following reply:—

"We did keep time, Sir, in our catches. Sneck up!"

That is, close up, shut up, or, as is said now, "bung up,"—emphatically, "We kept true time;" and the probability is, that in saying this, Sir Toby would accompany the words with the action of pushing an imaginary door; or sneck up.

In the country parts of Lancashire, and indeed throughout the North of England, and it appears Scotland also, the term "sneck the door" is used indiscriminately with "shut the door" or "toin't dur." And there can be little doubt but that this provincialism was known to Shakspeare, as his works are full of such; many of which have either been passed over by his commentators, or have been wrongly noted, as the one now under consideration.

Shakspeare was essentially a man of the people; his learning was from within, not from colleges or schools, but from the universe and himself. He wrote the language of the people; that is, the common every-day language of his time: and hence mere classical scholars have more than once mistaken him, and most egregiously misinterpreted him, as I propose to show in some future Notes.

R.R.

FOLK LORE

Death-bed Superstition. (No. 20. p. 315.).—The practice of opening doors and boxes when a person dies, is founded on the idea that the ministers of purgatorial pains took the soul as it escaped from the body, and flattening it against some closed door (which alone would serve the purpose), crammed it into the hinges and hinge openings; thus the soul in torment was likely to be miserably pinched and squeezed by the movement on casual occasion of such door or lid: an open or swinging door frustrated this, and the fiends had to try some other locality. The friends of the departed were at least assured that they were not made the unconscious instruments of torturing the departed in their daily occupations. The superstition prevails in the North as well as in the West of England; and a similar one exists in the South of Spain, where I have seen it practised.

Among the Jews at Gibraltar, at which place I have for many years been a resident, there is also a strange custom when a death occurs in the house; and this consists in pouring away all the water contained in any vessel, the superstition being that the angel of death may have washed his sword therein.

TREBOR.

May Marriages.—It so happened that yesterday I had both a Colonial Bishop and a Home Archdeacon taking part in the services of my church, and visiting at my house; and, by a singular coincidence, both had been solicited by friends to perform the marriage ceremony not later than to-morrow, because in neither case would the bride-elect submit to be married in the month of May. I find that it is a common notion amongst ladies, that May marriages are unlucky.

Can any one inform me whence this prejudice arose?

ALFRED GATTY.

Ecclesfield, April 29. 1850.

[This superstition is as old as Ovid's time, who tells us in his Fasti,

"Nec viduæ tædis eadem, nec virginis apta

Tempora. Quæ nupsit non diuturna fuit.

Hac quoque de causa (si te proverbia tangunt),

Mense malas Maio nubere vulgus ait."

The last line, as our readers may remember, (see ante, No. 7. p. 97.), was fixed on the gates of Holyrood on the morning (16th of May) after the marriage of Mary Queen of Scots and Bothwell.]

Throwing Old Shoes at a Wedding.—At a wedding lately, the bridesmaids, after accompanying the bride to the hall-door, threw into the carriage, on the departure of the newly-married couple, a number of old shoes which they had concealed somewhere. On inquiry, I find this custom is not uncommon; I should be glad to be favoured with any particulars respecting its origin and meaning, and the antiquity of it.

ARUN.

[We have some NOTES on the subject of throwing Old Shoes after a person as a means of securing them good fortune, which we hope to insert in an early Number.]

Sir Thomas Boleyn's Spectre.—Sir Thomas Boleyn, the father of the unfortunate Queen of Henry VIII., resided at Blickling, distant about fourteen miles from Norwich, and now the residence of the dowager Lady Suffield. The spectre of this gentleman is believed by the vulgar to be doomed, annually, on a certain night in the year, to drive, for a period of 1000 years, a coach drawn by four headless horses, over a circuit of twelve bridges in that vicinity. These are Aylsham, Burgh, Oxnead, Buxton, Coltishall, the two Meyton bridges, Wroxham, and four others whose names I do not recollect. Sir Thomas carries his head under his arm, and flames issue from his mouth. Few rustics are hardy enough to be found loitering on or near those bridges on that night; and my informant averred, that he was himself on one occasion hailed by this fiendish apparition, and asked to open a gate, but "he warn't sich a fool as to turn his head; and well a' didn't, for Sir Thomas passed him full gallop like:" and he heard a voice which told him that he (Sir Thomas) had no power to hurt such as turned a deaf ear to his requests, but that had he stopped he would have carried him off.

This tradition I have repeatedly heard in this neighbourhood from aged persons when I was a child, but I never found but one person who had ever actually seen the phantom. Perhaps some of your correspondents can give some clue to this extraordinary sentence. The coach and four horses is attached to another tradition I have heard in the west of Norfolk; where the ancestor of a family is reported to drive his spectral team through the old walled-up gateway of his now demolished mansion, on the anniversary of his death: and it is said that the bricks next morning have ever been found loosened and fallen, though as constantly repaired. The particulars of this I could easily procure by reference to a friend.

E.S.T.

P.S. Another vision of Headless Horse is prevalent at Caistor Castle, the seat of the Fastolfs.

Shuck the Dog-fiend.—This phantom I have heard many persons in East Norfolk, and even Cambridgeshire, describe as having seen as a black shaggy dog, with fiery eyes, and of immense size, and who visits churchyards at midnight. One witness nearly fainted away at seeing it, and on bringing his neighbours to see the place where he saw it, he found a large spot as if gunpowder had been exploded there. A lane in the parish of Overstrand is called, after him, Shuck's Lane. The name appears to be a corruption of "shag," as shucky is the Norfolk dialect for "shaggy." Is not this a vestige of the German "Dog-fiend?"

E.S.T.