Various

Notes and Queries, Number 09, December 29, 1849

OUR PROGRESS

We have this week been called upon to take a step which neither our best friends nor our own hopes could have anticipated. Having failed in our endeavours to supply by other means the increasing demand for complete sets of our "NOTES AND QUERIES," we have been compelled to reprint the first four numbers.

It is with no slight feelings of pride and satisfaction that we record the fact of a large impression of a work like the present not having been sufficient to meet the demand,—a work devoted not to the witcheries of poetry or to the charms of romance, but to the illustration of matters of graver import, such as obscure points of national history, doubtful questions of literature and bibliography, the discussion of questionable etymologies, and the elucidation of old world customs and observances.

What Mr. Kemble lately said so well with reference to archæology, our experience justifies us in applying to other literary inquiries:—

"On every side there is evidence of a generous and earnest co-operation among those who have devoted themselves to special pursuits; and not only does this tend of itself to widen the general basis, but it supplies the individual thinker with an ever widening foundation for his own special study."

And whence arises this "earnest co-operation?" Is it too much to hope that it springs from an increased reverence for the Truth, from an intenser craving after a knowledge of it—whether such Truth regards an event on which a throne depended, or the etymology of some household word now familiar only to

"Hard-handed men who work in Athens here?"

We feel that the kind and earnest men who honour our "NOTES AND QUERIES" with their correspondence, hold with Bacon, that

"Truth, which only doth judge itself, teacheth that the inquiry of Truth, which is the love-making or wooing of it—the knowledge of Truth, which is the presence of it—and the belief of Truth, which is the enjoying of it—is the sovereign good of human nature."

We believe that it is under the impulse of such feelings that they have flocked to our columns—that the sentiment has found its echo in the breast of the public, and hence that success which has attended our humble efforts. The cause is so great, that we may well be pardoned if we boast that we have had both hand and heart in it.

And so, with all the earnestness and heartiness which befit this happy season, when

"No spirit stirs abroad;

The nights are wholesome; when no planet strikes,

No fairy takes, no witch hath power to charm,

So hallow'd and so gracious is the time,"

do we greet all our friends, whether contributors or readers, with the good old English wish,

A MERRY CHRISTMAS AND A HAPPY NEW YEAR!

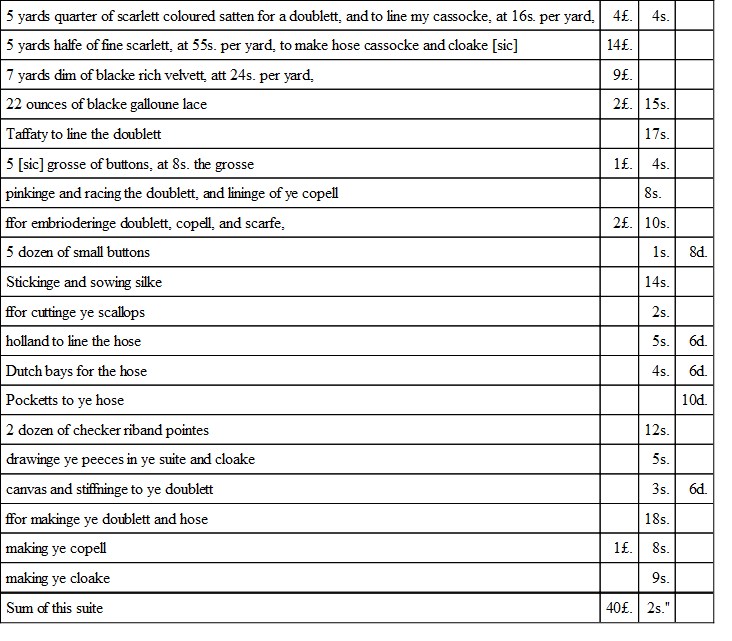

SIR E. DERING'S HOUSEHOLD BOOK

The muniment chests of our old established families are seldom without their quota of "household books." Goodly collections of these often turn up, with records of the expenditure and the "doings" of the household, through a period of two or more centuries. These documents are of incalculable value in giving us a complete insight into the domestic habits of our ancestors. Many a note is there, well calculated to illustrate the pages of the dramatist or the biographer, and even the accuracy of the historian's statements may often be tested by some of the details which find their way into these accounts; as for the more peculiar province of the antiquary, there is always a rich store of materials. Every change of costume is there; the introduction of new commodities, new luxuries, and new fashions, the varying prices of the passing age. Dress in all its minute details, modes of travelling, entertainments, public and private amusements, all, with their cost, are there: and last, though not least, touches of individual character ever and anon present themselves with the force of undisguised and undeniable truth. Follow the man through his pecuniary transactions with his wife and children, his household, his tenantry, nay, with himself, and you have more of his real character than the biographer is usually able to furnish. In this view, a man's "household book" becomes an impartial autobiography.

I would venture to suggest that a corner of your paper might sometimes be profitably reserved for "notes" from these household books; there can be little doubt that your numerous readers would soon furnish you with abundant contributions of most interesting matter.

While suggesting the idea, there happens to lie open before me the account-book of the first Sir Edward Dering, commencing with the day on which he came of age, when, though his father was still living, he felt himself an independent man.

One of his first steps, however, was to qualify this independence by marriage. If family tradition be correct, he was as heedless and impetuous in this the first important step of his life, as he seems to have been in his public career. The lady was Elizabeth, daughter of Sir Nicholas Tufton, afterwards created Earl of Thanet.

In almost the first page of his account-book he enters all the charges of this marriage, the different dresses he provided, his wedding presents, &c. As to his bride, the first pleasing intelligence which greeted the young knight, after passing his pledge to take her for "richer for poorer," was, that the latter alternative was his. Sir Nicholas had jockied the youth out of the promised "trousseau," and handed over his daughter to Sir Edward, with nothing but a few shillings in her purse. She came unfurnished with even decent apparel, and her new lord had to supply her forthwith with necessary clothing. In a subsequent page, when he comes to detail the purchases which he was, in consequence, obliged to make for his bride, he gives full vent to his feelings on this niggardly conduct of the father, and, in recording the costs of his own outfit, his very first words have a smack of bitterness in them, which is somewhat ludicrous—

"Medio de donte leporum

Surgit amari aliquid."

He seems to sigh over his own folly and vanity in preparing a gallant bridal for one who met it so unbecomingly.

"1619.

"My DESPERATE quarter! the 3d quarter from Michaelmas unto New Year's Day.

I must not occupy more of your space this week by extending these extracts. If likely to supply useful "notes" to your readers, they shall have, in some future number, the remainder of the bridegroom's wardrobe. In whatever niggardly array the bride came to her lord's arms, he, at least, was pranked and decked in all the apparel of a young gallant, an exquisite of the first water, for this was only one of several rich suits which he provided for his marriage outfit; and then follows a list of costly gloves and presents, and all the lavish outlay of this his "desperate quarter."

In some future number, too, if acceptable to your readers, you shall be furnished with a list of other and better objects of expenditure from this household book; for Sir Edward, albeit, as Clarendon depicts him, the victim of his own vanity, was worthy of better fame than is yet been his lot to acquire.

He was a most accomplished scholar and a learned antiquary. He had his foibles, it is true, but they were redeemed by qualities of high and enduring excellence. The eloquence of his parliamentary speeches has elicited the admiration of Southey; to praise them therefore now were superfluous. The noble library which he formed at Surrenden, and the invaluable collection of charters which he amassed there, during his unhappily brief career, testify to his ardour in literary pursuits. The library and a large part of the MSS. are unhappily dispersed. Of the former, all that remains to tell of what it once was, are a few scattered notices among the family records, and the titles of books, with their cost, as they are entered in the weekly accounts of our "household book." Of the latter there yet remain a few thousand charters and rolls, some of them of great interest, with exquisite seals attached. I shall be able occasionally to send you a few "notes" on these heads, from the "household book," and, in contemplating the remains of this unrivalled collection of its day, I can well bespeak the sympathy of every true-hearted "Chartist" and Bibliographer, in the lament which has often been mine—"Quanta fuisti cum tantæ sint reliquiæ!"

LAMBERT B. LARKING.Ryarsh Vicarage, Dec. 12. 1849.

BERKELEY'S THEORY OF VISION VINDICATED

In reply to the query of "B.G." (p. 107. of your 7th No.), I beg to say that Bishop Berkeley's Theory of Vision Vindicated does not occur either in the 4to. or 8vo. editions of his collected works; but there is a copy of it in the library of Trinity College, Dublin, from which I transcribe the full title as follows:—

"The Theory of Vision, or Visual Language, shewing the immediate Presence and Providence of a Deity, vindicated and explained. By the author of Alciphron, or The Minute Philosopher.

"Acts, xvii. 28.

"In Him we live, and move, and have our being.

"Lond. Printed for J. Tonson in the Strand.

"MDCCXXXIII."

Some other of the author's tracts have also been omitted in his collected works; but, as I am now answering "a Query," and not making "a Note," I shall reserve what I might say of them for another opportunity. The memory of Berkeley is dear to every member of this University; and therefore I hope you will permit me to say one word, in defence of his character, against Dugald Stewart's charge of having been "provoked," by Lord Shaftesbury's Characteristics, "to a harshness equally unwonted and unwarranted."

Mr. Stewart can scarcely suppose to have seen the book upon which he pronounces this most "unwarranted" criticism. The tract was not written in reply to the Characteristics, but was an answer to an anonymous letter published in the Daily Post-Boy of September 9th, 1732, which letter Berkeley has reprinted at the end of his pamphlet. The only allusion to the writer of this letter which bears the slightest tinge of severity occurs at the commencement of the tract. Those who will take the trouble of perusing the anonymous letter, will see that it was richly deserved; and I think it can scarcely, with any justice, be censured as unbecomingly harsh, or in any degree unwarranted. The passage is as follows:—

[After mentioning that an ill state of health had prevented his noticing this letter sooner, the author adds,] "This would have altogether excused me from a controversy upon points either personal or purely speculative, or from entering the lists of the declaimers, whom I leave to the triumph of their own passions. And indeed, to one of this character, who contradicts himself and misrepresents me, what answer can be made more than to desire his readers not to take his word for what I say, but to use their own eyes, read, examine, and judge for themselves? And to their common sense I appeal."

The remainder of the tract is occupied with a philosophical discussion of the subject of debate, in a style as cool and as free from harshness as Dugald Stewart could desire, and containing, as far as I can see, nothing inconsistent with the character of him, who was described by his contemporaries as the possessor of "every virtue under heaven."

JAMES H. TODD.Trin. Coll. Dublin, Dec. 20. 1849.