полная версия

Various

Cowboy Songs, and Other Frontier Ballads

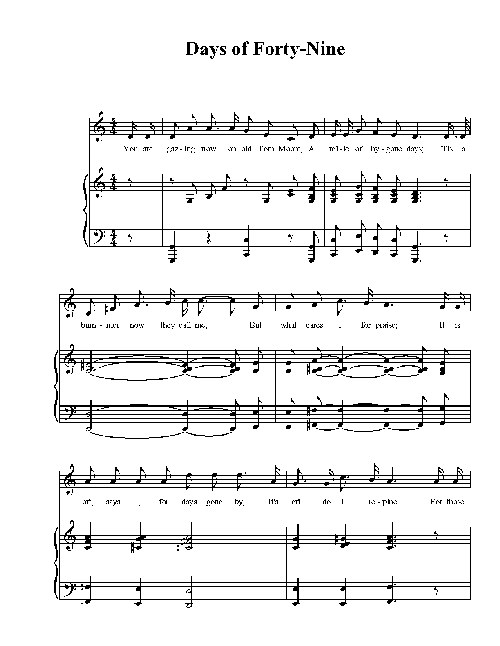

THE DAYS OF FORTY-NINE

We are gazing now on old Tom Moore,

A relic of bygone days;

'Tis a bummer, too, they call me now,

But what cares I for praise?

It's oft, says I, for the days gone by,

It's oft do I repine

For the days of old when we dug out the gold

In those days of Forty-Nine.

My comrades they all loved me well,

The jolly, saucy crew;

A few hard cases, I will admit,

Though they were brave and true.

Whatever the pinch, they ne'er would flinch;

They never would fret nor whine,

Like good old bricks they stood the kicks

In the days of Forty-Nine.

There's old "Aunt Jess," that hard old cuss,

Who never would repent;

He never missed a single meal,

Nor never paid a cent.

But old "Aunt Jess," like all the rest,

At death he did resign,

And in his bloom went up the flume

In the days of Forty-Nine.

There is Ragshag Jim, the roaring man,

Who could out-roar a buffalo, you bet,

He roared all day and he roared all night,

And I guess he is roaring yet.

One night Jim fell in a prospect hole,—

It was a roaring bad design,—

And in that hole Jim roared out his soul

In the days of Forty-Nine.

There is Wylie Bill, the funny man,

Who was full of funny tricks,

And when he was in a poker game

He was always hard as bricks.

He would ante you a stud, he would play you a draw,

He'd go you a hatful blind,—

In a struggle with death Bill lost his breath

In the days of Forty-Nine.

There was New York Jake, the butcher boy,

Who was fond of getting tight.

And every time he got on a spree

He was spoiling for a fight.

One night Jake rampaged against a knife

In the hands of old Bob Sine,

And over Jake they held a wake

In the days of Forty-Nine.

There was Monte Pete, I'll ne'er forget

The luck he always had,

He would deal for you both day and night

Or as long as he had a scad.

It was a pistol shot that lay Pete out,

It was his last resign,

And it caught Pete dead sure in the door

In the days of Forty-Nine.

Of all the comrades that I've had

There's none that's left to boast,

And I am left alone in my misery

Like some poor wandering ghost.

And as I pass from town to town,

They call me the rambling sign,

Since the days of old and the days of gold

And the days of Forty-Nine.

JOE BOWERS

My name is Joe Bowers,

I've got a brother Ike,

I came here from Missouri,

Yes, all the way from Pike.

I'll tell you why I left there

And how I came to roam,

And leave my poor old mammy,

So far away from home.

I used to love a gal there,

Her name was Sallie Black,

I asked her for to marry me,

She said it was a whack.

She says to me, "Joe Bowers,

Before you hitch for life,

You ought to have a little home

To keep your little wife."

Says I, "My dearest Sallie,

O Sallie, for your sake,

I'll go to California

And try to raise a stake."

Says she to me, "Joe Bowers,

You are the chap to win,

Give me a kiss to seal the bargain,"—

And I throwed a dozen in.

I'll never forget my feelings

When I bid adieu to all.

Sal, she cotched me round the neck

And I began to bawl.

When I begun they all commenced,

You never heard the like,

How they all took on and cried

The day I left old Pike.

When I got to this here country

I hadn't nary a red,

I had such wolfish feelings

I wished myself most dead.

At last I went to mining,

Put in my biggest licks,

Came down upon the boulders

Just like a thousand bricks.

I worked both late and early

In rain and sun and snow,

But I was working for my Sallie

So 'twas all the same to Joe.

I made a very lucky strike

As the gold itself did tell,

For I was working for my Sallie,

The girl I loved so well.

But one day I got a letter

From my dear, kind brother Ike;

It came from old Missouri,

Yes, all the way from Pike.

It told me the goldarndest news

That ever you did hear,

My heart it is a-bustin'

So please excuse this tear.

I'll tell you what it was, boys,

You'll bust your sides I know;

For when I read that letter

You ought to seen poor Joe.

My knees gave 'way beneath me,

And I pulled out half my hair;

And if you ever tell this now,

You bet you'll hear me swear.

It said my Sallie was fickle,

Her love for me had fled,

That she had married a butcher,

Whose hair was awful red;

It told me more than that,

It's enough to make me swear,—

It said that Sallie had a baby

And the baby had red hair.

Now I've told you all that I can tell

About this sad affair,

'Bout Sallie marrying the butcher

And the baby had red hair.

But whether it was a boy or girl

The letter never said,

It only said its cussed hair

Was inclined to be red.

THE COWBOY'S DREAM2

Last night as I lay on the prairie,

And looked at the stars in the sky,

I wondered if ever a cowboy

Would drift to that sweet by and by.

Roll on, roll on;

Roll on, little dogies, roll on, roll on,

Roll on, roll on;

Roll on, little dogies, roll on.

The road to that bright, happy region

Is a dim, narrow trail, so they say;

But the broad one that leads to perdition

Is posted and blazed all the way.

They say there will be a great round-up,

And cowboys, like dogies, will stand,

To be marked by the Riders of Judgment

Who are posted and know every brand.

I know there's many a stray cowboy

Who'll be lost at the great, final sale,

When he might have gone in the green pastures

Had he known of the dim, narrow trail.

I wonder if ever a cowboy

Stood ready for that Judgment Day,

And could say to the Boss of the Riders,

"I'm ready, come drive me away."

For they, like the cows that are locoed,

Stampede at the sight of a hand,

Are dragged with a rope to the round-up,

Or get marked with some crooked man's brand.

And I'm scared that I'll be a stray yearling,—

A maverick, unbranded on high,—

And get cut in the bunch with the "rusties"

When the Boss of the Riders goes by.

For they tell of another big owner

Whose ne'er overstocked, so they say,

But who always makes room for the sinner

Who drifts from the straight, narrow way.

They say he will never forget you,

That he knows every action and look;

So, for safety, you'd better get branded,

Have your name in the great Tally Book.

THE COWBOY'S LIFE3

The bawl of a steer,

To a cowboy's ear,

Is music of sweetest strain;

And the yelping notes

Of the gray cayotes

To him are a glad refrain.

And his jolly songs

Speed him along,

As he thinks of the little gal

With golden hair

Who is waiting there

At the bars of the home corral.

For a kingly crown

In the noisy town

His saddle he wouldn't change;

No life so free

As the life we see

Way out on the Yaso range.

His eyes are bright

And his heart as light

As the smoke of his cigarette;

There's never a care

For his soul to bear,

No trouble to make him fret.

The rapid beat

Of his broncho's feet

On the sod as he speeds along,

Keeps living time

To the ringing rhyme

Of his rollicking cowboy song.

Hike it, cowboys,

For the range away

On the back of a bronc of steel,

With a careless flirt

Of the raw-hide quirt

And a dig of a roweled heel!

The winds may blow

And the thunder growl

Or the breezes may safely moan;—

A cowboy's life

Is a royal life,

His saddle his kingly throne.

Saddle up, boys,

For the work is play

When love's in the cowboy's eyes,—

When his heart is light

As the clouds of white

That swim in the summer skies.

THE KANSAS LINE

Come all you jolly cowmen, don't you want to go

Way up on the Kansas line?

Where you whoop up the cattle from morning till night

All out in the midnight rain.

The cowboy's life is a dreadful life,

He's driven through heat and cold;

I'm almost froze with the water on my clothes,

A-ridin' through heat and cold.

I've been where the lightnin', the lightnin' tangled in my eyes,

The cattle I could scarcely hold;

Think I heard my boss man say:

"I want all brave-hearted men who ain't afraid to die

To whoop up the cattle from morning till night,

Way up on the Kansas line."

Speaking of your farms and your shanty charms,

Speaking of your silver and gold,—

Take a cowman's advice, go and marry you a true and lovely little wife,

Never to roam, always stay at home;

That's a cowman's, a cowman's advice,

Way up on the Kansas line.

Think I heard the noisy cook say,

"Wake up, boys, it's near the break of day,"—

Way up on the Kansas line,

And slowly we will rise with the sleepy feeling eyes,

Way up on the Kansas line.

The cowboy's life is a dreary, dreary life,

All out in the midnight rain;

I'm almost froze with the water on my clothes,

Way up on the Kansas line.

THE COWMAN'S PRAYER

Now, O Lord, please lend me thine ear,

The prayer of a cattleman to hear,

No doubt the prayers may seem strange,

But I want you to bless our cattle range.

Bless the round-ups year by year,

And don't forget the growing steer;

Water the lands with brooks and rills

For my cattle that roam on a thousand hills.

Prairie fires, won't you please stop?

Let thunder roll and water drop.

It frightens me to see the smoke;

Unless it's stopped, I'll go dead broke.

As you, O Lord, my herd behold,

It represents a sack of gold;

I think at least five cents a pound

Will be the price of beef the year around.

One thing more and then I'm through,—

Instead of one calf, give my cows two.

I may pray different from other men

But I've had my say, and now, Amen.

THE MINER'S SONG4

In a rusty, worn-out cabin sat a broken-hearted leaser,

His singlejack was resting on his knee.

His old "buggy" in the corner told the same old plaintive tale,

His ore had left in all his poverty.

He lifted his old singlejack, gazed on its battered face,

And said: "Old boy, I know we're not to blame;

Our gold has us forsaken, some other path it's taken,

But I still believe we'll strike it just the same.

"We'll strike it, yes, we'll strike it just the same,

Although it's gone into some other's claim.

My dear old boy don't mind it, we won't starve if we don't find it,

And we'll drill and shoot and find it just the same.

"For forty years I've hammered steel and tried to make a strike,

I've burned twice the powder Custer ever saw.

I've made just coin enough to keep poorer than a snake.

My jack's ate all my books on mining law.

I've worn gunny-sacks for overalls, and 'California socks,'

I've burned candles that would reach from here to Maine,

I've lived on powder, smoke, and bacon, that's no lie, boy, I'm not fakin',

But I still believe we'll strike it just the same.

"Last night as I lay sleeping in the midst of all my dream

My assay ran six ounces clear in gold,

And the silver it ran clean sixteen ounces to the seam,

And the poor old miner's joy could scarce be told.

I lay there, boy, I could not sleep, I had a feverish brow,

Got up, went back, and put in six holes more.

And then, boy, I was chokin' just to see the ground I'd broken;

But alas! alas! the miner's dream was o'er.

"We'll strike it, yes, we'll strike it just the same,

Although it's gone into some other's claim.

My dear old boy, don't mind it, we won't starve if we don't find it,

And I still believe I'll strike it just the same."

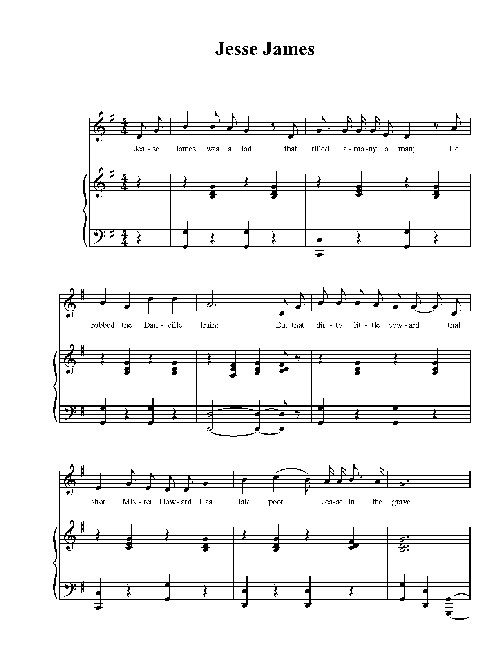

JESSE JAMES

Jesse James was a lad that killed a-many a man;

He robbed the Danville train.

But that dirty little coward that shot Mr. Howard

Has laid poor Jesse in his grave.

Poor Jesse had a wife to mourn for his life,

Three children, they were brave.

But that dirty little coward that shot Mr. Howard

Has laid poor Jesse in his grave.

It was Robert Ford, that dirty little coward,

I wonder how he does feel,

For he ate of Jesse's bread and he slept in Jesse's bed,

Then laid poor Jesse in his grave.

Jesse was a man, a friend to the poor,

He never would see a man suffer pain;

And with his brother Frank he robbed the Chicago bank,

And stopped the Glendale train.

It was his brother Frank that robbed the Gallatin bank,

And carried the money from the town;

It was in this very place that they had a little race,

For they shot Captain Sheets to the ground.

They went to the crossing not very far from there,

And there they did the same;

With the agent on his knees, he delivered up the keys

To the outlaws, Frank and Jesse James.

It was on Wednesday night, the moon was shining bright,

They robbed the Glendale train;

The people they did say, for many miles away,

It was robbed by Frank and Jesse James.

It was on Saturday night, Jesse was at home

Talking with his family brave,

Robert Ford came along like a thief in the night

And laid poor Jesse in his grave.

The people held their breath when they heard of Jesse's death,

And wondered how he ever came to die.

It was one of the gang called little Robert Ford,

He shot poor Jesse on the sly.

Jesse went to his rest with his hand on his breast;

The devil will be upon his knee.

He was born one day in the county of Clay

And came from a solitary race.

This song was made by Billy Gashade,

As soon as the news did arrive;

He said there was no man with the law in his hand

Who could take Jesse James when alive.

POOR LONESOME COWBOY

I ain't got no father,

I ain't got no father,

I ain't got no father,

To buy the clothes I wear.

I'm a poor, lonesome cowboy,

I'm a poor, lonesome cowboy,

I'm a poor, lonesome cowboy

And a long ways from home.

I ain't got no mother,

I ain't got no mother,

I ain't got no mother

To mend the clothes I wear.

I ain't got no sister,

I ain't got no sister,

I ain't got no sister

To go and play with me.

I ain't got no brother,

I ain't got no brother,

I ain't got no brother

To drive the steers with me.

I ain't got no sweetheart,

I ain't got no sweetheart,

I ain't got no sweetheart

To sit and talk with me.

I'm a poor, lonesome cowboy,

I'm a poor, lonesome cowboy,

I'm a poor, lonesome cowboy

And a long ways from home.

BUENA VISTA BATTLEFIELD

On Buena Vista battlefield

A dying soldier lay,

His thoughts were on his mountain home

Some thousand miles away.

He called his comrade to his side,

For much he had to say,

In briefest words to those who were

Some thousand miles away.

"My father, comrade, you will tell

About this bloody fray;

My country's flag, you'll say to him,

Was safe with me to-day.

I make a pillow of it now

On which to lay my head,

A winding sheet you'll make of it

When I am with the dead.

"I know 'twill grieve his inmost soul

To think I never more

Will sit with him beneath the oak

That shades the cottage door;

But tell that time-worn patriot,

That, mindful of his fame,

Upon this bloody battlefield

I sullied not his name.

"My mother's form is with me now,

Her will is in my ear,

And drop by drop as flows my blood

So flows from her the tear.

And oh, when you shall tell to her

The tidings of this day,

Speak softly, comrade, softly speak

What you may have to say.

"Speak not to her in blighting words

The blighting news you bear,

The cords of life might snap too soon,

So, comrade, have a care.

I am her only, cherished child,

But tell her that I died

Rejoicing that she taught me young

To take my country's side.

"But, comrade, there's one more,

She's gentle as a fawn;

She lives upon the sloping hill

That overlooks the lawn,

The lawn where I shall never more

Go forth with her in merry mood

To gather wild-wood flowers.

"Tell her when death was on my brow

And life receding fast,

Her looks, her form was with me then,

Were with me to the last.

On Buena Vista's bloody field

Tell her I dying lay,

And that I knew she thought of me

Some thousand miles away."

WESTWARD HO

I love not Colorado

Where the faro table grows,

And down the desperado

The rippling Bourbon flows;

Nor seek I fair Montana

Of bowie-lunging fame;

The pistol ring of fair Wyoming

I leave to nobler game.

Sweet poker-haunted Kansas

In vain allures the eye;

The Nevada rough has charms enough

Yet its blandishments I fly.

Shall Arizona woo me

Where the meek Apache bides?

Or New Mexico where natives grow

With arrow-proof insides?

Nay, 'tis where the grizzlies wander

And the lonely diggers roam,

And the grim Chinese from the squatter flees

That I'll make my humble home.

I'll chase the wild tarantula

And the fierce cayote I'll dare,

And the locust grim, I'll battle him

In his native wildwood lair.

Or I'll seek the gulch deserted

And dream of the wild Red man,

And I'll build a cot on a corner lot

And get rich as soon as I can.

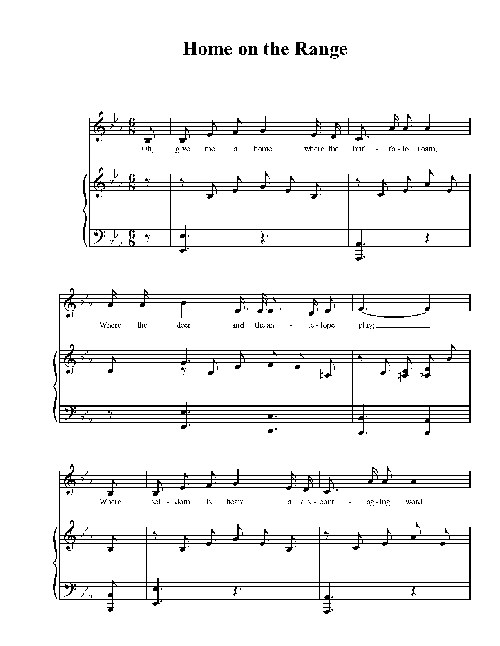

A HOME ON THE RANGE

Oh, give me a home where the buffalo roam,

Where the deer and the antelope play,

Where seldom is heard a discouraging word

And the skies are not cloudy all day.

Home, home on the range,

Where the deer and the antelope play;

Where seldom is heard a discouraging word

And the skies are not cloudy all day.

Where the air is so pure, the zephyrs so free,

The breezes so balmy and light,

That I would not exchange my home on the range

For all of the cities so bright.

The red man was pressed from this part of the West,

He's likely no more to return

To the banks of Red River where seldom if ever

Their flickering camp-fires burn.

How often at night when the heavens are bright

With the light from the glittering stars,

Have I stood here amazed and asked as I gazed

If their glory exceeds that of ours.

Oh, I love these wild flowers in this dear land of ours,

The curlew I love to hear scream,

And I love the white rocks and the antelope flocks

That graze on the mountain-tops green.

Oh, give me a land where the bright diamond sand

Flows leisurely down the stream;

Where the graceful white swan goes gliding along

Like a maid in a heavenly dream.

Then I would not exchange my home on the range,

Where the deer and the antelope play;

Where seldom is heard a discouraging word

And the skies are not cloudy all day.

Home, home on the range,

Where the deer and the antelope play;

Where seldom is heard a discouraging word

And the skies are not cloudy all day.

TEXAS RANGERS

Come, all you Texas rangers, wherever you may be,

I'll tell you of some troubles that happened unto me.

My name is nothing extra, so it I will not tell,—

And here's to all you rangers, I am sure I wish you well.

It was at the age of sixteen that I joined the jolly band,

We marched from San Antonio down to the Rio Grande.

Our captain he informed us, perhaps he thought it right,

"Before we reach the station, boys, you'll surely have to fight."

And when the bugle sounded our captain gave command,

"To arms, to arms," he shouted, "and by your horses stand."

I saw the smoke ascending, it seemed to reach the sky;

The first thought that struck me, my time had come to die.

I saw the Indians coming, I heard them give the yell;

My feelings at that moment, no tongue can ever tell.

I saw the glittering lances, their arrows round me flew,

And all my strength it left me and all my courage too.

We fought full nine hours before the strife was o'er,

The like of dead and wounded I never saw before.

And when the sun was rising and the Indians they had fled,

We loaded up our rifles and counted up our dead.

And all of us were wounded, our noble captain slain,

And the sun was shining sadly across the bloody plain.

Sixteen as brave rangers as ever roamed the West

Were buried by their comrades with arrows in their breast.

'Twas then I thought of mother, who to me in tears did say,

"To you they are all strangers, with me you had better stay."

I thought that she was childish, the best she did not know;

My mind was fixed on ranging and I was bound to go.

Perhaps you have a mother, likewise a sister too,

And maybe you have a sweetheart to weep and mourn for you;

If that be your situation, although you'd like to roam,

I'd advise you by experience, you had better stay at home.

I have seen the fruits of rambling, I know its hardships well;

I have crossed the Rocky Mountains, rode down the streets of hell;

I have been in the great Southwest where the wild Apaches roam,

And I tell you from experience you had better stay at home.

And now my song is ended; I guess I have sung enough;

The life of a ranger I am sure is very tough.

And here's to all you ladies, I am sure I wish you well,

I am bound to go a-ranging, so ladies, fare you well.

THE MORMON BISHOP'S LAMENT

I am a Mormon bishop and I will tell you what I know.

I joined the confraternity some forty years ago.

I then had youth upon my brow and eloquence my tongue,

But I had the sad misfortune then to meet with Brigham Young.

He said, "Young man, come join our band and bid hard work farewell,

You are too smart to waste your time in toil by hill and dell;

There is a ripening harvest and our hooks shall find the fool

And in the distant nations we shall train them in our school."

I listened to his preaching and I learned all the role,

And the truth of Mormon doctrines burned deep within my soul.

I married sixteen women and I spread my new belief,

I was sent to preach the gospel to the pauper and the thief.

'Twas in the glorious days when Brigham was our only Lord and King,

And his wild cry of defiance from the Wasatch tops did ring,

'Twas when that bold Bill Hickman and that Porter Rockwell led,

And in the blood atonements the pits received the dead.

They took in Dr. Robertson and left him in his gore,

And the Aiken brothers sleep in peace on Nephi's distant shore.

We marched to Mountain Meadows and on that glorious field

With rifle and with hatchet we made man and woman yield.

'Twas there we were victorious with our legions fierce and brave.

We left the butchered victims on the ground without a grave.

We slew the load of emigrants on Sublet's lonely road

And plundered many a trader of his then most precious load.

Alas for all the powers that were in the by-gone time.

What we did as deeds of glory are condemned as bloody crime.

No more the blood atonements keep the doubting one in fear,

While the faithful were rewarded with a wedding once a year.

As the nation's chieftain president says our days of rule are o'er

And his marshals with their warrants are on watch at every door,

Old John he now goes skulking on the by-roads of our land,

Or unknown he keeps in hiding with the faithful of our band.

Old Brigham now is stretched beneath the cold and silent clay,

And the chieftains now are fallen that were mighty in their day;

Of the six and twenty women that I wedded long ago

There are two now left to cheer me in these awful hours of woe.

The rest are scattered where the Gentile's flag's unfurled

And two score of my daughters are now numbered with the world.

Oh, my poor old bones are aching and my head is turning gray;

Oh, the scenes were black and awful that I've witnessed in my day.

Let my spirit seek the mansion where old Brigham's gone to dwell,

For there's no place for Mormons but the lowest pits of hell.