Various

Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 63, No. 391, May, 1848

CHAPTER IX

At this time we were living in what may be called a very respectable style for people who made no pretence to ostentation. On the skirts of a large village, stood a square red brick house, about the date of Queen Anne. Upon the top of the house was a balustrade; why, heaven knows – for nobody, except our great tom-cat Ralph, ever walked upon the leads – but so it was, and so it often is in houses from the time of Elizabeth, yea, even to that of Victoria. This balustrade was divided by low piers, on each of which was placed a round ball. The centre of the house was distinguishable by an architrave, in the shape of a triangle, under which was a niche, probably meant for a figure, but the figure was not forthcoming. Below this was the window (encased with carved pilasters) of my dear mother's little sitting-room; and lower still, raised on a flight of six steps, was a very handsome-looking door. All the windows, with smallish panes and largish frames, were relieved with stone copings; – so that the house had an air of solidity and well-to-do-ness about it – nothing tricky on the one hand, nothing decayed on the other. The house stood a little back from the garden gates, which were large, and set between two piers surmounted with vases. Many might object, that in wet weather you had to walk some way to your carriage; but we obviated that objection by not keeping a carriage. To the right of the house the enclosure contained a little lawn, a laurel hermitage, a square pond, a modest green-house, and half-a-dozen plots of mignionette, heliotrope, roses, pinks, sweet-william, &c. To the left spread the kitchen-garden, lying screened by espaliers yielding the finest apples in the neighbourhood, and divided by three winding gravel-walks, of which the extremest was backed by a wall, whereon, as it lay full south, peaches, pears, and nectarines sunned themselves early into well-remembered flavour. This walk was appropriated to my father. Book in hand, he would, on fine days, pace to and fro, often stopping, dear man, to jot down a pencil-note, gesticulate, or soliloquise. And there, when not in his study, my mother would be sure to find him. In these deambulations, as he called them, he had generally a companion so extraordinary, that I expect to be met with a hillalu of incredulous contempt when I specify it. Nevertheless I vow and protest that it is strictly true, and no invention of an exaggerating romancer. It happened one day that my mother had coaxed Mr Caxton to walk with her to market. By the way they passed a sward of green, on which sundry little boys were engaged upon the lapidation, or stoning, of a lame duck. It seemed that the duck was to have been taken to market, when it was discovered not only to be lame, but dyspeptic; perhaps some weed had disagreed with its ganglionic apparatus, poor thing. However that be, the good-wife had declared that the duck was good for nothing; and upon the petition of her children, it had been consigned to them for a little innocent amusement, and to keep them out of harm's way. My mother declared that she never before saw her lord and master roused to such animation. He dispersed the urchins, released the duck, carried it home, kept it in a basket by the fire, fed it and physicked it till it recovered; and then it was consigned to the square pond. But lo! the duck knew its benefactor; and whenever my father appeared outside his door, it would catch sight of him, flap from the pond, gain the lawn, and hobble after him, (for it never quite recovered the use of its left leg,) till it reached the walk by the peaches; and there sometimes it would sit, gravely watching its master's deambulations; sometimes stroll by his side, and, at all events, never leave him, till, at his return home, he fed it with his own hands; and, quacking her peaceful adieus, the nymph then retired to her natural element.

With the exception of my mother's dining-room, the principal sitting-rooms – that is, the study, the dining-room, and what was emphatically called the "best drawing-room," which was only occupied on great occasions – looked south. Tall beeches, firs, poplars, and a few oaks, backed the house, and indeed surrounded it on all sides but the south; so that it was well sheltered from the winter cold and the summer heat. Our principal domestic, in dignity and station, was Mrs Primmins, who was waiting gentlewoman, housekeeper, and tyrannical dictatrix of the whole establishment. Two other maids, a gardener, and a footman composed the rest of the serving household. Save a few pasture-fields, which he let, my father was not troubled with land. His income was derived from the interest of about £15,000, partly in the three per cents, partly on mortgage; and what with my mother and Mrs Primmins, this income always yielded enough to satisfy my father's single hobby for books, pay for my education, and entertain our neighbours, rarely, indeed, at dinner, but very often at tea. My dear mother boasted that our society was very select. It consisted chiefly of the clergyman and his family, two old maids who gave themselves great airs, a gentleman who had been in the East India service, and who lived in a large white house at the top of the hill; some half-a-dozen squires and their wives and children; Mr Squills, still a bachelor: And once a-year cards were exchanged – and dinners too – with certain aristocrats, who inspired my mother with a great deal of unnecessary awe; since she declared they were the most good-natured easy people in the world, and always stuck their cards in the most conspicuous part of the looking-glass frame over the chimney-place of the best drawing-room. Thus you perceive that our natural position was one highly creditable to us, proving the soundness of our finances and the gentility of our pedigree, of which – but more hereafter. At present I content myself with saying on that head, that even the proudest of the neighbouring squirearchs always spoke of us as a very ancient family. But all my father ever said, to evince pride of ancestry, was in honour of William Caxton, citizen and printer in the reign of Edward IV. – "Clarum et venerabile nomen!" an ancestor a man of letters might be justly vain of.

"Heus," said my father, stopping short, and lifting his eyes from the Colloquies of Erasmus, "salve multum, jucundissime."

Uncle Jack was not much of a scholar, but he knew enough Latin to answer, "Salve tantundem, mi frater."

My father smiled approvingly. "I see you comprehend true urbanity, or politeness, as we phrase it. There is an elegance in addressing the husband of your sister as brother. Erasmus commends it in his opening chapter, under the head of 'Salutandi formulæ.' And indeed," added my father thoughtfully, "there is no great difference between politeness and affection. My author here observes that it is polite to express salutation in certain minor distresses of nature. One should salute a gentleman in yawning, salute him in hiccuping, salute him in sneezing, salute him in coughing; – and that evidently because of your interest in his health; for he may dislocate his jaw in yawning, and the hiccup is often a symptom of grave disorder, and sneezing is perilous to the small blood-vessels of the head, and coughing is either a tracheal, bronchial, pulmonary, or ganglionic affection."

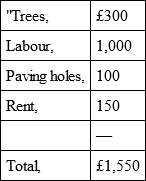

"Very true. The Turks always salute in sneezing, and they are a remarkably polite people," said Uncle Jack. "But, my dear brother, I was just looking with admiration at these apple-trees of yours. I never saw finer. I am a great judge of apples. I find, in talking with my sister, that you make very little profit of them. That's a pity. One might establish a cider orchard in this county. You can take your own fields in hand; you can hire more, so as to make the whole, say a hundred acres. You can plant a very extensive apple-orchard on a grand scale. I have just run through the calculations; they are quite startling. Take 40 trees per acre – that's the proper average – at 1s. 6d. per tree; 4000 trees for 100 acres £300;, labour of digging, trenching, say £10 an acre – total for 100 acres, £1000. Pave the bottoms of the holes, to prevent the tap-root striking down into the bad soil – oh, I am very close and careful, you see, in all minutiæ,! – always was – pave 'em with rubbish and stones, 6d. a hole; that, for 4000 trees the 100 acres is £100. Add the rent of the land, at 30s. an acre, £150. And how stands the total?" Here Uncle Jack proceeded rapidly ticking off the items with his fingers: —

That's your expense. Mark. – Now to the profit. Orchards in Kent realise £100 an acre, some even £150; but let's be moderate, say only £50 an acre, and your gross profit per year, from a capital of £1550, will be £5000. – £5000 a year. Think of that, brother Caxton. Deduct 10 per cent, or £500 a-year, for gardeners' wages, manure, &c., and the net product is £4500. Your fortune's made, man – it is made – I wish you joy!" And Uncle Jack rubbed his hands.

"Bless me, father," said eagerly the young Pisistratus, who had swallowed with ravished ears every syllable and figure of this inviting calculation, "Why, we should be as rich as Squire Rollick; and then, you know, sir, you could keep a pack of fox-hounds!"

"And buy a large library," added Uncle Jack, with more subtle knowledge of human nature as to its appropriate temptations. "There's my friend the archbishop's collection to be sold."

Slowly recovering his breath, my father gently turned his eyes from one to the other; and then, laying his left hand on my head, while with the right he held up Erasmus rebukingly to Uncle Jack, he said —

"See how easily you can sow covetousness and avidity in the youthful mind! Ah, brother!"

"You are too severe, sir. See how the dear boy hangs his head! Fie! – natural enthusiasm of his years – 'gay hope by fancy fed,' as the poet says. Why, for that fine boy's sake, you ought not to lose so certain an occasion of wealth, I may say, untold. For, observe, you will form a nursery of crabs; each year you go on grafting and enlarging your plantation, renting, nay, why not buying, more land? Gad, sir! in twenty years you might cover half the county; but say you stop short at 2000 acres, why, the net profit is £90,000 a-year. A duke's income – a duke's – and going a begging as I may say."

"But stop," said I modestly; "the trees don't grow in a year. I know when our last apple tree was planted – it is five years ago – it was then three years old, and it only bore one half bushel last autumn."

"What an intelligent lad it is! – Good head there. Oh, he'll do credit to his great fortune, brother," said Uncle Jack approvingly. "True, my boy. But in the meanwhile we could fill the ground, as they do in Kent, with gooseberries and currants, or onions and cabbages. Nevertheless, considering we are not great capitalists, I am afraid we must give up a share of our profits to diminish our outlay. So, harkye, Pisistratus – (look at him, brother – simple as he stands there, I think he's born with a silver spoon in his mouth) – harkye, now to the mysteries of speculation. Your father shall quietly buy the land, and then, presto! we will issue a prospectus, and start a company. Associations can wait five years for a return. Every year, meanwhile, increases the value of the shares. Your father takes, we say, fifty shares at £50 each, paying only an instalment of £2 a share. He sells 35 shares at cent per cent. He keeps the remaining 15, and his fortune's made all the same; only it's not quite so large as if he had kept the whole concern in his own hands. What say you now, brother Caxton? 'Visne edere pomum?' as we used to say at school."

"I don't want a shilling more than I have got," said my father, resolutely. "My wife would not love me better; my food would not nourish me more; my boy would not, in all probability, be half so hardy, or a tenth part so industrious; and – "

"But," interrupted Uncle Jack, pertinaciously, and reserving his grand argument for the last, "the good you would confer on the community – the progress given to the natural productions of your country, the wholesome beverage of cider, brought within cheap reach of the labouring classes. If it was only for your sake, should I have urged this question? should I now? is it in my character? But for the sake of the public! mankind! of our fellow-creatures! Why, sir, England could not get on if gentlemen like you had not a little philanthropy and speculation."

"Papæ!" exclaimed my father, "to think that England can't get on without turning Augustine Caxton into an apple-merchant! My dear Jack, listen. You remind me of a colloquy in this book; wait a bit – here it is —Pamphagus and Cocles– 'Cocles recognises his friend who had been absent for many years, by his eminent and remarkable nose. – Pamphagus says, rather irritably, that he is not ashamed of his nose. 'Ashamed of it! no, indeed,' says Cocles: 'I never saw a nose that could be put to so many uses!' 'Ha,' says Pamphagus, (whose curiosity is aroused,) 'uses! what uses?' Whereon (lepidissime frater!) Cocles, with eloquence rapid as yours, runs on with a countless list of the uses to which so vast a development of the organ can be applied. 'If the cellar was deep, it could sniff up the wine like an elephant's trunk, – if the bellows were missing, it could blow the fire, – if the lamp was too glaring, it could suffice for a shade, – it would serve as a speaking-trumpet to a herald, – it could sound a signal of battle in the field, – it would do for a wedge in wood-cutting, – a spade for digging, – a scythe for mowing, – an anchor in sailing; till Pamphagus cries out, 'Lucky dog that I am! and I never knew before what a useful piece of furniture I carried about with me.'" My father paused and strove to whistle, but that effort at harmony failed him – and he added, smiling, "So much for my apple trees, brother John. Leave them to their natural destination of filling tarts and dumplings."

Uncle Jack looked a little discomposed for a moment; but he then laughed with his usual heartiness, and saw that he had not yet got to my father's blind side. I confess that my revered parent rose in my estimation after that conference; and I began to see that a man may not be quite without common-sense, though he is a scholar. Indeed, whether it was that Uncle Jack's visit acted as a gentle stimulant to his relaxed faculties, or that I, now grown older and wiser, began to see his character more clearly, I date from those summer holidays the commencement of that familiar and endearing intimacy which ever after existed between my father and myself. Often I deserted the more extensive rambles of Uncle Jack, or the greater allurements of a cricket match in the village, or a day's fishing in Squire Rollick's preserves, for a quiet stroll with my father by the old peach wall; – sometimes silent, indeed, and already musing over the future, while he was busy with the past, but amply rewarded when, suspending his lecture, he would pour forth hoards of varied learning, rendered amusing by his quaint comments, and that Socratic satire which only fell short of wit because it never passed into malice. At some moments, indeed, the vein ran into eloquence; and with some fine heroic sentiment in his old books, his stooping form rose erect, his eye flashed; and you saw that he had not been originally formed and wholly meant for the obscure seclusion in which his harmless days now wore contentedly away.

CHAPTER IX

"Egad, sir, the county is going to the dogs! Our sentiments are not represented in parliament or out of it. The County Mercury has ratted, and be hanged to it! and now we have not one newspaper in the whole shire to express the sentiments of the respectable part of the community!"

This speech was made on the occasion of one of the rare dinners given by Mr and Mrs Caxton to the grandees of the neighbourhood, and uttered by no less a person than Squire Rollick, of Rollick Hall, chairman of the quarter sessions.

I confess that I, (for I was permitted on that first occasion not only to dine with the guests, but to outstay the ladies, in virtue of my growing years, and my promise to abstain from the decanters) – I confess, I say, that I, poor innocent, was puzzled to conjecture what sudden interest in the county newspaper could cause Uncle Jack to prick up his ears like a warhorse at the sound of the drum, and rush so incontinently across the interval between Squire Rollick and himself. But the mind of that deep and truly knowing man was not to be plumbed by a chit of my age. You could not fish for the shy salmon in that pool with a crooked pin and a bobbin, as you would for minnows; or, to indulge in a more worthy illustration, you could not say of him, as St Gregory saith of the streams of Jordan, "a lamb could wade easily through that ford."

"Not a county newspaper to advocate the rights of – " here my uncle stopped, as if at a loss, and whispered in my ear, "What are his politics?" "Don't know," answered I. Uncle Jack intuitively took down from his memory the phrase most readily at hand, and added, with a nasal intonation, "the rights of our distressed fellow-creatures!"

My father scratched his eyebrow with his forefinger, as he was apt to do when doubtful; the rest of the company – a silent set – looked up.

"Fellow-creatures!" said Mr Rollick – "fellow-fiddlesticks!"

Uncle Jack was clearly in the wrong box. He drew out of it cautiously – "I mean," said he, "our respectable fellow-creatures;" and then suddenly it occurred to him that a "County Mercury" would naturally represent the agricultural interest, and that if Mr Rollick said that the "County Mercury ought to be hanged," he was one of those politicians who had already begun to call the agricultural interest "a Vampire." Flushed with that fancied discovery, Uncle Jack rushed on, intending to bear along with the stream, thus fortunately directed, all the "rubbish"1 subsequently shot into Covent Garden and the Hall of Commerce.

"Yes, respectable fellow-creatures, men of capital and enterprise! For what are these country squires compared to our wealthy merchants? What is this agricultural interest that professes to be the prop of the land?"

"Professes!" cried Squire Rollick, "It is the prop of the land, and as for those manufacturing fellows who have bought up the Mercury – "

"Bought up the Mercury, have they, the villains!" cried Uncle Jack, interrupting the Squire, and now bursting into full scent – "Depend upon it, sir, it is a part of a diabolical system of buying up, which must be exposed manfully. – Yes, as I was saying, what is that agricultural interest which they desire to ruin? which they declare to be so bloated – which they call 'a vampire!' they the true blood-suckers, the venomous millocrats! Fellow-creatures, sir! I may well call distressed fellow-creatures, the members of that much suffering class of which you yourself are an ornament. What can be more deserving of our best efforts for relief, than a country gentleman like yourself, we'll say – of a nominal £5000 a-year – compelled to keep up an establishment, pay for his fox-hounds, support the whole population by contributions to the poor rates, support the whole church by tithes; all justice, jails, and prosecutions by the county rates, all thoroughfares by the highway rates – ground down by mortgages, Jews, or jointures; having to provide for younger children; enormous expenses for cutting his woods, manuring his model farm, and fattening huge oxen till every pound of flesh costs him five pounds sterling in oil-cake; and then the lawsuits necessary to protect his rights; plundered on all hands by poachers, sheep-stealers, dog-stealers, church-wardens, overseers, gardeners, gamekeepers, and that necessary rascal, his steward. If ever there was a distressed fellow-creature in the world, it is a country gentleman with a great estate."

My father evidently thought this an exquisite piece of banter; for by the corner of his mouth I saw that he chuckled inly.

Squire Rollick, who had interrupted the speech by sundry approving exclamations, particularly at the mention of poor rates, tithes, county rates, mortgages, and poachers, here pushed the bottle to Uncle Jack, and said civilly – "There's a great deal of truth in what you say, Mr Tibbets. The agricultural interest is going to ruin; and when it does, I would not give that for Old England!" and Mr Rollick snapped his finger and thumb. "But what is to be done – done for the county? There's the rub."

"I was just coming to that," quoth Uncle Jack. "You say that you have not a county paper that upholds your cause, and denounces your enemies."

"Not since the Whigs bought the – shire Mercury."

"Why, good heavens! Mr Rollick, how could you suppose that you will have justice done you, if at this time of day you neglect the press? The press, sir – there it is – air we breathe! What you want is a great national – no, not a national – A PROVINCIAL proprietary weekly journal, supported liberally and steadily by that mighty party whose very existence is at stake. Without such a paper, you are gone, you are dead, extinct, defunct, buried alive; with such a paper, well conducted, well edited by a man of the world, of education, of practical experience in agriculture and human nature, mines, corn, manure, insurances, acts of parliament, cattle shows, the state of parties, and the best interests of society – with such a man and such a paper, you will carry all before you. But it must be done by subscription, by association, by co-operation, by a grand provincial Benevolent Agricultural, Anti-innovating Society."

"Egad, sir, you are right!" said Mr Rollick, slapping his thigh; "and I'll ride over to our Lord-Lieutenant to-morrow. His eldest son ought to carry the county."

"And he will, if you encourage the press, and set up a journal," said Uncle Jack, rubbing his hands, and then gently stretching them out, and drawing them gradually together, as if he were already enclosing in that airy circle the unsuspecting guineas of the unborn association.

All happiness dwells more in the hope than the possession; and at that moment, I dare be sworn that Uncle Jack felt a livelier rapture, circum præcordia, warming his entrails, and diffusing throughout his whole frame of five feet eight the prophetic glow of the Magna Diva Moneta, than if he had enjoyed for ten years the actual possession of King Crœsus's privy purse.

"I thought Uncle Jack was not a Tory," said I to my father the next day.

My father, who cared nothing for politics, opened his eyes.

"Are you a Tory or a Whig, papa?"

"Um," said my father – "there's a great deal to be said on both sides of the question. You see, my boy, that Mrs Primmins has a great many moulds for our butter-pats; sometimes they come up with a crown on them, sometimes with the more popular impress of a cow. It is all very well for those who dish up the butter to print it according to their taste, or in proof of their abilities; it is enough for us to butter our bread, say grace, and pay for the dairy. Do you understand?"

"Not a bit, sir."

"Your namesake Pisistratus was wiser than you, then," said my father. "And now let us feed the duck. Where's your uncle?"

"He has borrowed Mr Squills's mare, sir, and gone with Squire Rollick to the great lord they were talking of."

"Oho!" said my father, "brother Jack is going to print his butter!"

And indeed Uncle Jack played his cards so well on this occasion, and set before the Lord-Lieutenant, with whom he had a personal interview, so fine a prospectus, and so nice a calculation, that before my holidays were over, he was installed in a very handsome office in the county town, with private apartments over it, and a salary of £500 a-year – for advocating the cause of his distressed fellow-creatures, including noblemen, squires, yeomanry, farmers, and all yearly subscribers in the New Proprietary Agricultural, Anti-innovating – shire Weekly Gazette. At the head of his newspaper Uncle Jack caused to be engraved a crown supported by a flail and a crook, with the motto "Pro rege et grege," and that was the way in which Uncle Jack printed his pats of butter.