Various

Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 56, Number 350, December 1844

These two reports saved the country – we trust we shall not hereafter be compelled to add, only for a time – from its great impending misfortune. The circulation in England became metallic, with what success it is not for us to say, whilst Scotland was allowed to retain her paper currency with at least most perfect satisfaction to herself. One pregnant fact, however, it would be unpardonable for us to omit – as showing the stability of the northern system when compared with that practised in the south – that at the last investigation before a committee of the House of Commons in 1841, it was stated, that whereas in Scotland the whole loss sustained by the public from bank failures, for a century and a half, amounted to L. 32,000, the loss to the public, during the previous year in London alone, was estimated at ten times that amount!

Since 1826, we have had eighteen years' further experience of the system, without either detecting derangement in its organization, or the slightest diminution of confidence on the part of the public. There has been no interference with the metallic currency of England. Forgery is a crime now utterly unknown, as is also coining, beyond the insignificant counterfeits of the silver issue. This, in fact, is a great advantage which we have above the English in point of security, since we are exempt from the risk of receiving into circulation either base or light sovereigns, and since the banks provide for the deterioration of their notes by tear and wear, whilst the holder of a light sovereign has to pay the difference between the standard and the deficient weight. When we reflect upon the small amount of the wages of a labouring man, it is manifest how important this branch of the subject is; for were gold allowed in Scotland to supersede the paper currency, a fresh and most dangerous impetus would be given to the crime of coining; and there cannot be a doubt, that in the remoter districts, where gold is utterly unknown, a most lamentable series of frauds would be perpetrated, with little risk of detection, but with the cruelest consequences to the poor and illiterate classes.

We are not, however, inclined to adopt the opinion expressed by the committee of the House of Commons, to the extent of admitting that it would be either politic or just to disturb the whole banking system of a country on account of private frauds, whether forgeries or the fabrication of counterfeit coin. If their opinion was a sound one, the weight of evidence is now upon our side of the argument; but we hold that the interests at stake are far too great to be affected by any such minor details. If any new circumstance has arisen "to affect the relations of trade and intercourse between Scotland and England," we at least are wholly unconscious of the occurrence, and, of course, it is the duty of those who meditate a change to point it out, in order that it may be thoroughly scrutinized. Internally, the business of the banks has been increasing, and, commensurate with that increase, there has been a vast addition to the number of branch banks spread over the face of the country; so that, whereas in 1825 there was but one office for every 13,170 individuals, in 1841 there was an office for every 6600 of the population. This is plainly the inevitable effect of competition; but lest that increase should be founded upon by our opponents as a proof of over-circulation, we shall say a few words upon the subject of the exchange between the banks themselves, which is a leading feature of our whole system, and the most complete check against over-trading which human ingenuity could devise. Fortunately we have ample data for our statement in the evidence tendered to the committee on banks of issue in 1841.

It is right, however, to premise that, strictly speaking, there are not more, nay, there are positively fewer banks in Scotland at the present moment than there were in 1825, though the amount of paid-up capital in the banks is more than doubled. It is the branches alone which make this astonishing increase. Now, as a branch is merely a local agency of the parent bank, established at a distance for the sake of outlying business, the number of parties engaged in banking who are responsible to the public is not thereby increased, nor is the amount in circulation extended. In fact, the multiplication of the branch banks has been of extraordinary benefit to the public, by affording the inhabitants of even the remotest districts a ready, easy, and favourite method of deposit, and by extinguishing all risks of credit. Further, it has this manifest advantage, that the manager of the branch bank has far greater facilities of ascertaining the character, habits, and pursuits of those persons who may have received the advantage of a cash-credit accommodation, and can immediately report to his superiors any circumstances which may render it advisable that the credit should be contracted or withdrawn. So far are we from holding that the multiplication of branch banks is any evil or incumbrance, that we look upon it as an increased security not only to the banker but the dealer. The latter, in fact, is the principal gainer; because a competition among the banks has always the effect of heightening the rate of interest given upon deposits, and of lowering the rates charged upon advances. Nor does this give any impetus to rash speculation on the part of the dealer, but directly the reverse. The deposits always increase with the advancing rate of interest; and experience has shown, that it is not until that rate declines to two per cent that deposited money is usually withdrawn, which is the signal of commencing speculation. To the mere speculator the banks afford no facilities, but the reverse. Their cash credits are only granted for the daily operations of persons actively engaged in trade, business, or commerce. So soon as that credit appears to be converted into a different channel, it is withdrawn, as alike dangerous to the user and unprofitable to the bank which has given it.

Of thirty-one banks in Scotland which issue notes, five only are chartered– that is, the responsibility of the proprietors in those established is confined to the amount of their subscribed capital. The remaining twenty-six are, with one or two exceptions, joint-stock banks, and the proprietors are liable to the public for the whole of the bank responsibilities to the last shilling of their private fortunes. The number of persons connected with these banks as shareholders is very great, almost every man of opulence in the country being a holder of stock to a greater or a less amount. That some jealousy must exist among so many competitors in a limited field, is an obvious matter of inference. Such jealousy, however, has only operated for the advantage of the public, by the maintenance of a common and vigilant watch upon the manner in which the affairs of each establishment are conducted, and against the intrusion of any new parties into the circle whose capital does not seem to warrant the likelihood of their ultimate stability. Accordingly, the Scottish bankers have arranged amongst themselves a mutual system of exchange, as stringent as if it had the force of statute, by means of which an over-issue of notes becomes a matter of perfect impossibility. Twice in every week the whole notes deposited with the different bank offices in Scotland are regularly interchanged. Now, with this system in operation, it is perfectly ludicrous to suppose that any bank would issue its paper rashly for the sake of an extended circulation. The whole notes in circulation throughout Scotland return to their respective banks in a period averaging from ten to eleven days in urban, and from a fortnight to three weeks in rural districts. In consequence of the rate of interest allowed by the banks, no person has any inducement to keep bank paper by him, but the reverse, and the general practice of the country is to keep the circulation at as low a rate as possible. The numerous branch banks which are situated up and down the country, are the means of taking the notes of their neighbours out of the circle as speedily as possible. In this way it is not possible for the circulation to be more than what is absolutely necessary for the transactions of the country.

If, therefore, any bank had been so rash as to grant accommodation without proper security, merely for the sake of obtaining a circulation, in ten days, or a fortnight at the furthest, it is compelled to account with the other banks for every note they have received. If it does not hold enough of their paper to redeem its own upon exchange, it is compelled to pay the difference in exchequer bills, a certain amount of which every bank is bound by mutual agreement to hold, the fractional parts of each thousand pounds being payable in Bank of England notes or in gold. In this way over-trading, in so far as regards the issue of paper, is so effectually guarded and controlled, that it would puzzle Parliament, with all its conceded conventional wisdom, to devise any plan alike so simple and expeditious.

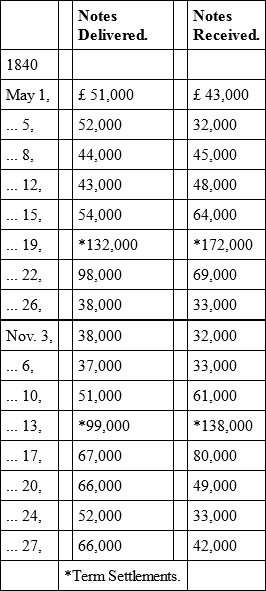

The amount of notes at present in circulation throughout Scotland is estimated at three millions, or at the very utmost three millions and a half. At certain times of the year, such as the great legal terms of Whitsunday and Martinmas, when money is universally paid over and received, there is, of course, a corresponding increase of issue for the moment which demands an extra supply of notes. It is never considered safe for a bank to have a smaller amount of notes in stock than the average amount which is out in circulation; so that the whole amount of bank-notes, both in circulation and in hand, may be calculated at seven millions. The fluctuation at the above terms is so remarkable, that we are tempted to give an account of the number of notes delivered and received by the bank of Scotland in exchange with other banks during the months of May and November 1840: —

It will be seen from the above table how rapidly the system of bank exchange absorbs the over-issue, and how instantaneously the paper drawn from one bank finds its way into the hands of another.

If further proof were required of the absurdity of the notion, that a paper circulation has a necessary tendency to over-issue, the following fact is conclusive. The banking capital in Scotland has more than doubled between the years 1825 and 1840 – a triumphant proof of their increased stability; whilst the circulation has been nearly stationary, but, if any thing, rather diminished than otherwise. We quote from a report to the Glasgow Chamber of Commerce.

"The first return of the circulation was made in Scotland in 1825. Every one knows the extraordinary advance which Scotland has made between that period and 1840; for instance, in the former of these years, she manufactured 55,000 bales of cotton, in the latter, 120,000 bales. In 1826, the produce of the iron furnaces was 33,500 tons; in 1840, about 250,000 tons. In 1826, the banking capital of Scotland was £4,900,000; in 1840, it was about £10,000,000; yet with all this progress in industry and wealth, the circulation of notes, which in 1825 varied from £3,400,000 to £4,700,000, was in 1839 from £2,960,000 to £3,670,000, and in the first three months of 1840, £2,940,000."

We are induced to dwell the more strongly upon these facts, because we have strong suspicions that our opponents will endeavour to get at our monetary system by raising the senseless cry of over-issue – senseless at any time as a political maxim, it being the grossest fallacy to maintain that an increased issue is the cause of national distress, unless, indeed, it were possible to suppose that bankers were madmen enough to dispense their paper without receiving a proper equivalent – not only senseless, but positively nefarious, when the clear broad fact stares them in the face, that Scotland has in fifteen years thrown double the amount of capital into its banking establishments, increased its productions in a threefold, and in some cases a sevenfold ratio, augmented its population by nearly half a million, (one-fifth part of the whole,) and yet kept its circulation so low as to exhibit an actual decrease.

If we were called upon to state the cause of this certainly singular fact, we should, without any hesitation, attribute it to the great increase of the bank branches. The establishment of a branch in a remote locality, has invariably, from the thrifty habits of the Scottish people, absorbed all the paper which otherwise would have been hoarded for a time, and left in the hands of the holders without any interest. It would thus seem, from practice, that the doctrines of the political economists upon this head are absolutely fallacious; that the increase of banks, supposing these banks to issue paper and to give interest on deposits, has a direct tendency to check over-circulation, and in fact does partially supersede it.

With these facts before us, we consider that the measure of last session, prohibiting any further issue of notes beyond those already taken out by the banks, is almost a dead letter. We have not the least fear, that under any circumstances there can be a call for a larger circulation; at the same time, we demur to the policy which ties our hands needlessly, and we object to all restriction where no case for restriction has been shown. We look upon that measure as especially unfair to the younger banks, whose circulation is not yet established, and whose progress has thus received a material check, from no fault of their own, but from want of ministerial notice. With every system where competition is the acknowledged principle, it is clearly impolitic to interfere; nor can we avoid the painful conviction, that this first measure, though comparatively light and generally unimportant, was put out by way of feeler, in order to test the temper of the Scottish people – to ascertain whether eighteen years of prosperity might not have made them a little more supple and pliable, and whether they were likely to oppose to innovation the same amount of obstinate resistance as before. It is dangerous to permit the smallest rent to be made in a wall, for, with dexterous management, that rent may be so widened, as to bring down the whole superstructure.

In the absence of any distinct charge against the Scottish banks, which were so honourably acquitted in 1826, we shall confine our further observations to the effects which must necessarily follow upon a change in the established currency. In doing so, we shall conjure up no phantoms of imaginary distress, but merely state the consequences as they have already been explained to Parliament by men who are far better able to judge than ourselves, and even – with deference be it said – than our legislators, of the substitution in Scotland of a metallic for a paper currency. That measure is to be considered, 1st, as it will affect the banks; 2dly, as it will affect the public.

The general effect of the change would be to derange the whole of the present system. The first result would probably be the abolition and withdrawal of all the branch banks throughout the kingdom. These offices are at present fed with notes which are payable at the office of the parent bank, whither, accordingly, they invariably return. These are supplied to them at no risk or expense, whereas the transmission of gold would not only be dangerous, but so expensive as entirely to swallow up the profits. Add to this, that the banks would no longer be able to allow interest on deposit accounts; at all events such interest would be merely fractional, and too insignificant to induce the continuance of the saving habit which now so fortunately prevails. In short, all the branch business would stagnate and die. The consequence of the removal of the branch banks would be the ruin of the Highlands.

Mr Kennedy's account of the profits of banking will explain the sweeping nature of the change. "A banker's profits are derived from two sources – the brokerage upon the deposit money, and the returns that he gets from his circulation. We have tried to estimate the amount of deposits in Scotch banks, and we calculate it at about thirty millions; that, at the brokerage of one and a half per cent, yields £450,000 annually. The currency we will take at three millions, and that, at 5 per cent, is £150,000: making a gross sum of £600,000, which is the whole profit derived from banking in Scotland. Out of that are to be deducted the whole of the charges. From these figures it will be perceived that the gross profit of the currency is a fourth part of the gross profit of banking; but the expense that falls upon the currency is not so large as the expense that falls upon the other portions of the banking business; so that I should be inclined to say that, upon the average, the profit derived from the circulation bore the proportion of a third to the aggregate profit of banking."

Assuming Mr Kennedy's calculation to be correct, the profit of £600,000, derived by the banks, would thus be reduced to £400,000 by the change of currency.

But the diminution would not rest there. The brokerage upon the deposits – that is, the difference between the rates of interest given and charged by the banks – on the present calculated amount of deposits, is £450,000. from which the charges are deducted. Now we have already seen that the banks find it necessary, in order to encourage deposits, to give a liberal rate of interest; and we have also seen that, whenever interest falls to two per cent, the deposits are gradually withdrawn, and a period of speculation begins. Let us hear Mr John Thomson, of the Royal Bank, on the effect of a gold currency on deposit accounts: – "I think, on the operating deposits, we could scarcely allow any interest, and on the more steady deposits, that the rate of interest would require to be very considerably reduced."

It follows, therefore, according to all experience, that, if no interest were allowed, the deposits would be generally withdrawn for investment elsewhere; and thus another serious reduction would be made from the already attenuated amount of the Scottish bankers' profits. But besides the loss of profit on the small notes, there would be a further loss sustained by the necessity of keeping up a large stock of gold in the coffers of the bank. Hear Mr Thomson again upon this subject: —

"It would occasion greater loss than the mere profit on the small notes, inasmuch as at present we have to keep on hand a large stock of small notes, to fill up in the circle those that are taken from it by tear and wear, and to meet occasional demands. The present mode of keeping up this stock, which consists of our own notes, is done at no expense; if we had to keep a corresponding stock of gold to keep up the circle in the same proportion, we would, perhaps, if there is £1000 dispersed in small notes, require to keep up a protecting fund of £500 to meet that, or something in that proportion. So that, upon the whole, if there was £1,800,000, which was the sum assumed of notes in circulation, withdrawn, we would require to fill up the place, £1,800,000, in gold, and in order to fill our coffers with a protecting stock, perhaps from seven to nine hundred thousand, to keep up the stock; and, in addition to that, there is the expense of transmission from one part of the country to another, and the bringing it from London."

The small note circulation is here estimated at £1,800,000 but there is no doubt that it is now considerably larger. Taking it, however, at Mr Thomson's calculation, what a fearful amount of unoccupied and inoperative capital is here! This, be it observed also, is only the first reserve, which at present is represented by the small notes of the bank. According to the later evidence of Mr Blair, the Scottish banks are in the habit of holding, besides this, a further reserve of gold and Bank of England notes, equal to a fourth of their circulation, without taking into account exchequer bills, or other convertible securities which bear interest.

Thus it follows, as a matter of course, that if the small notes were abolished, and a gold currency established, there would not be room in the country for one-fourth of the present number of banks. If the banks are removed, and more especially the branches, which must inevitably fall, we should like to know from any theoretical economist, even from Sir Robert Peel, how the country is to be supplied with money?

So much for the effect which the introduction of a metallic currency would have upon the banking establishments. Let us now see what would be the consequence of the change upon the interests of the public, who are the dealers.

Now, although we hold, that upon every principle of public expediency and justice, the legislature are bound to regard with particular tenderness the interests of a body of men, who, like the Scottish bankers, have not only established, but administered for such a long time, the monetary system of the country with stability, temperance, indulgence, and success, equally removed from weak facility and from grasping avidity of gain; we must, nevertheless, allow that the interests of the public are paramount to theirs, and that if it can be shown that the public will be gainers, although the bankers should be losers by the change, the sooner the metallic currency is established amongst us the better. Here is the true test of the clause in the Treaty of Union, providing that no alteration shall be made on laws which concern private right excepting for the evident utility of the subjects within Scotland. There shall be no interference with private rights if that interference is not to benefit the public; if it does so, private right must of course give way, according to a rule universally adopted by every civilized nation. In speaking of the public, we, of course, restrict ourselves to Scotland; for although the Treaty of Union is not, strictly speaking, a federal one, and in the larger points of policy and general government is very clearly one of incorporation, it has yet this important ingredient of federality in its conception, that the laws of each country and their administration are left separate and entire, as also their customs and usages, so long as the same do not interfere with one another. It is a sore point with the supporters of a metallic currency, and a sad discouragement to their theories, that they have never been able in any way to shake the confidence of the Scottish public in the stability of their national bankers. It was no use drawing invidious comparisons between a weighty glittering guinea, fresh started from the mint of Mammon, and the homely unpretending well-thumbed issue of the North; it was no use hinting that a system which professed to dispense with bullion must of necessity be a mere illusion, which would go down with the first blast of misfortune, as easily as its fragile notes could be dispersed before a breeze of wind. The shrewd Scotsman knew, what apparently the economist had forgotten, that the piece of gold exhibited by the latter was in itself but a representative, and not the reality of property; that the gold to be acquired must be bought; that all representation of wealth within a country must be conventional in order to have any value; and further, that however fragile the despised paper might appear, that it was by convention and by law the representative of things more weighty and more solid than metal – of the manufactures of the country, of its agricultural produce, and, finally, of the land itself; all which were mortgaged for its redemption. It was in vain to talk to him of the rates of foreign exchange in the mystic jargon of the Bourse. He knew well, that when the Scottish mint was abolished, and the bullion trade transferred to London, that branch of traffic was placed utterly beyond his reach. He knew further, that the circulation of Scotland did not ebb or flow in accordance with the fluctuation of foreign exchanges, but from causes which were always within the reach of his own ken and observance. All scrutiny beyond that he left to the bank, in the solvency of which he placed the most implicit confidence; and accordingly he dealt with it as freely and as confidently as his father and grandfather had done before him, and laughed the theories of the political economists to scorn. Such is no overcharged statement of the sentiments which the Scottish customer entertains; – is he right, or is he wrong? and how would the change affect him?

In the first place, he would receive no interest upon his deposit account. This point we have already touched upon, when proving that the banks would sustain great loss by the inevitable withdrawal of their deposits; but of course the profit to the bank is one thing, and the profit to the customer is another. An operating deposit account on which a fixed and universal rate of interest is paid, is a thing unknown in England. In that country, according to Mr John Gladstone, a Liverpool merchant, and a declared enemy to the Scottish currency, the bankers only give interest on deposits by special bargain, according to the length of time that these deposits shall be entrusted to their hands. This is clearly neither more nor less than permanent loan to the bank, and, like every other private contract, is arbitrary. But an operating deposit is a totally different matter, by which the circulation of the bank paper is promoted, and which acquires actual value from the frequency of its fluctuations. It is a system so easy in its working, that no householder in Scotland is without it; and for every shilling that he deposits in the bank, he receives regular interest, calculated from day to day, without any deduction or commission, at as high a rate as if he had left, for a stipulated period, a million of money unrecallable by him, to be employed in its trade by the bank. This is surely a great accommodation and encouragement to the trader. But see how the introduction of the metallic currency would affect us. Operating deposits there would be none; for, if the banker were not actually compelled to charge a certain per centage of commission, he would at least be able to pay no interest. Or let it be granted that, by great economy, (though we cannot well see how,) he could still afford to pay a diminished rate, the proportion would be too small to tempt the dealer to the constant system of deposit which now exists, and hoarding would be the inevitable result. Or suppose that the system of deposit should still continue in the large towns, what is to become of the country when the branch banks shall have been removed? A little topography might here be valuable, to correct the notions of the theorists, who would legislate precisely for the thinly inhabited districts of Kintail and Edderachylis, as they would for the town-covered surface of Lancashire.

But there would be more important losses to the public than the mere cessation of interest upon operating deposit accounts. All the witnesses who have been examined, agree that cash-credits must be immediately withdrawn. Of all the facilities that a mercantile country, or rather the foremost mercantile system of a country, can afford to industry, that of cash-credit is certainly the most unexceptionable. Take the case of a young man just about to start in business, whose connexion, habits, and education, are such as to give every possible augury for his future success. The res angustæ domi are probably hard upon him. He has no patrimony; his friends, though in fair credit, are not capitalists; and he has not of himself the opportunity of launching into trade, for the want of that one talent, which, if judiciously used, would in time multiply itself into ten. He cannot ask his friends to assist him in the discount of bills. Large as the affection of a Scotchman may be for some descriptions of paper, he has a kind of inherent repugnance to that sort of floating private currency, which in three or in six months is sure to return, coupled with an awkward protest, to his door. Probably in his own early experience, or in the days of his father, he has received a salutary lesson, better than a thousand treatises upon the law and practice of acceptance; and accordingly, while he will lend you his purse with readiness, he will not, for almost any consideration, subscribe his name to a bill. To persons thus situated, the accommodation granted by the bank cash-credits, is the greatest commercial boon that ever was devised; but as the committee of the House of Lords, in the report already quoted, has borne ample testimony in their favour, it is unnecessary for us to dwell with further minuteness on their utility.

We must again have recourse to Mr Thomson for an exposition of the reasons which, if a metallic currency were forced upon us, would lead to the discontinuance of the cash-credits. "I do not think the cash-credits would be maintained at all; the banker's profits might be made up by the charge of a commission on each credit; but it is not probable that the holders of accounts would pay at such a rate, if they could borrow money upon bills at a cheaper rate, which they would do. They would discount bills at five per cent. A banker would not be disposed to come under the obligation to give a running credit with a cash account, and thereby bind himself to keep in his hands a stock of gold to supply the daily operations of a cash-account, while he might find it perfectly convenient to discount a bill and give the money away at once." In short, it has been stated, and distinctly proved, that the difference to the trader between an operating cash-credit and accommodation by discount, is the difference between paying five and a quarter by discount, and two and a half per cent by cash-credit. Are our merchants and traders prepared or disposed to submit to such a sacrifice; more especially when it is considered, that a bank will often refuse to discount a bill for £100, when it would make no difficulty, from its opportunities of control, in granting a cash-credit for five times that amount?