Various

Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine — Volume 55, No. 342, April, 1844

To our surprise, the provisions on board the slaver were ample for the negroes, consisting of Monte Video dried beef, small beans, rice, and cassava flour. The cabin stores were profuse; lockers filled with ale and porter, barrels of wine, liqueurs of various sorts, cases of English pickles, raisins, &c. &c.; and its list of medicines amounted to almost the whole Materia Medica. On questioning the Spaniards as to the probability of extinguishing the slave-trade, their reply was, that though in the creeks of Brazil it might be difficult, yet it had grown a desperate adventure. Four vessels had been already taken on the east coast of Africa this year; but the venture is so lucrative, that the profits of a fifth which escaped, would probably more than compensate the loss of the four.

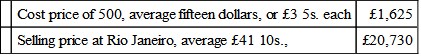

On the east coast negroes are paid for in money or coarse cottons, at the rate of eighteen dollars for men, and twelve for boys. At Rio Janeiro their value may be estimated at £52 for men, £41, 10s. for women, and £31 for boys. Thus, on a cargo of 500, at the mean price the profit will exceed £19,000—

While these enormous profits continue, it must be a matter of extreme difficulty to suppress the trade, especially while the principals, captains, and crews, have perfect impunity. At present, all that they suffer is the loss of their cargo. But if enactments were made, by which heavy fines and imprisonment were to be inflicted on the merchants to whom the expedition could be traced, and corporal punishment and transportation for life for the crews, and for the captains service as common sailors on board our frigates, we should soon find the ardour for the traffic diminished.

The voyage was slow from the frequent calms. By the 20th of April they had advanced only to the tropic, 350 miles. From day to day the sick among the negroes were dropping off. A large shark followed the ship, which they conceived might have gorged some of the corpses. He was caught, but the stomach was empty. When brought on the deck, he exhibited the usual and remarkable tenacity of life. Though his tail was chopped, and even his entrails taken out, in neither of which operations it exhibited any sign of sensation, yet no sooner was a bucket of salt water poured on it to wash the deck, than it began to flounder about and bite on all sides.

Symptoms of fever now began to appear on board, and the Portuguese cook died.

April 29.—A storm, the lightning intolerably vivid, flash succeeding flash with scarcely a sensible intermission; blue, red, and of a still more dazzling white, which made the eye shrink, lighting up every object on deck as clearly as at mid-day. All the winds of heaven seemed let loose, as it blew alternately from every point of the compass. The screams of distress from the sick and weak in the hold, were heard through the roar of the tempest. From the rolling and creaking, one might fancy every thing going asunder. The woman's shed on deck had been washed down, and the planks which formed its roof falling in a heap, a woman was found dead under the ruin.

May 1.—In this hemisphere, marking the approach of the cold weather, the naked negroes began to shiver, and their teeth to chatter.

May 3.—Another storm, with severe cold. Seven negroes were found dead this morning. The wretched beings had begun now to steal water and brandy from the hold. "None can tell," says the writer, "save he who has tried, the pangs of thirst which may excite them in that heated hold, many of them fevered by mortal disease. Their daily allowance of water is about a half pint in the morning, and the same quantity in the evening." This passage now became all storms. A heavy squall came on May 8, which continued next day a strong gale. The first object which met the eye in the morning, was three negroes dead on the deck.

May 11.—Another storm, heavier than any of the preceding ones. Towards evening the report of the helmsman was the gratifying one, that the heart of the gale was broke; yet a yellow haze overspread the setting sun, and it continued to blow as wildly as ever. Squalls rapidly succeeding each other mingled sea and air in one sheet of spray, blinding the eyes of the helmsman; waves towering high above us, tossing up the foam from their crests towards the sky, threatened to engulf the vessel at every moment. When the squalls, breaking heavily on the vessel, caused her to heel over, and the negroes to tumble one against each other in the hold, the shrieks of the sufferers through the darkness of the night, rising above the noise of the winds and waves, seemed of all horrors in this unhappy vessel the saddest. Dysentery now attacked the crew, and the boatswain's mate died. We pass over the melancholy details of this miserable voyage, in which disgusts and distresses of every kind seemed to threaten all on board with death, every day bringing its mortality. At last on Sunday, May 28th, the welcome sight of Cape Agulhas cheered them at the distance of ten miles. The weather was now fine, but the mortality continued, the fatal cases averaging four a-day. On the 1st of June eight were found dead in the morning; and, when the morning mist had cleared away, they found themselves within three miles of Simon's Bay. As soon as the Progresso anchored, the superintendent of the naval hospital came on board, and the writer descended with him for the last time to the slave hold. Accustomed as he had been to scenes of suffering, he was unable to endure a sight, surpassing all he could have conceived, he said, of human misery, and made a hasty retreat. The numbers who had died within the fifty days were 163. Even this was not all; for, on returning to the vessel next day, six corpses were added to the eight of the preceding day, and the fourteen were piled on deck for interment on the shore. A hundred of the healthiest negroes were landed at the pier to proceed in waggons to Cape Town; but though rescued from a state of extreme misery, the change seemed to excite anxiety and apprehension. Each of the men had received on landing a new warm jacket and trousers, and the women had each a new white blanket in addition to an under dress, and they were placed snugly in waggons; yet their countenances resembled those of condemned victims. Of the whole of the original cargo, not far short of one half had died. To what causes this horrible mortality must be imputed, it is not our purpose to decide; but that it did not arise from the original tendency of the negroes to sickness seems evident—the fact being, that of the fifty who were taken on board the frigate, but one had died at sea and one on shore. Within a few days the liberated negroes had acquired a more cheerful look, their first conception having been that they were to be devoured by the people of the country, and they were reluctant to eat, fearing that it was intended to fatten them for the purpose. However, the negroes in the colonies soon freed them from this apprehension.

We shall be rejoiced if the publicity given to this little but intelligent pamphlet by our means, may assist in drawing the attention of the influential classes to the subject. We fully believe that, if we were to look for the deepest misery that was ever inflicted in this world, and the greatest mass of it, we should find it in the slave-trade. It is the misery, not as in civilized life, of scattered individuals, but of multitudes, and a misery comprehending every other; sudden separation from every tie of the human heart, parent, child, spouse, and country; the misery of bodily affliction, disease, famine, storms, shipwreck, and ultimately slavery, with all its wretchedness of toil and tyranny for life. We certainly do not think it our duty to go to war for the object of teaching humanity to other nations. We must not attempt to heal the calamity of the African by the greatest of all calamities and crimes—an unnecessary war. But England has only to persevere sincerely and steadily, however calmly, and she will, by the blessing of that supreme Disposer of the ways of men, who desires the happiness of all his creatures, succeed in the extinction of a traffic which has brought a curse, and brings it at this hour, and will bring it deeper still, upon every nation which insults the laws of humanity and the dictates of religion, by dealing in the flesh and blood of man.

MOSLEM HISTORIES OF SPAIN. 3

THE ARABS OF CORDOVA

"The second day was that when Martel broke

The Mussulmen, delivering France opprest,

And in one mighty conflict, from the yoke

Of unbelieving Mecca saved the West."

SOUTHEY.

The Arab domination in Spain is the grand romance of European history. The splendid but mysterious fabric of Asiatic power and science is seen for age after age, like the fairy castle of St John, exalted far above the rugged plain of Frank semi-barbarism—till the spell is at last broken by the iron prowess of Christian chivalry; and the glittering edifice vanishes from the land as though it had never been, leaving, like the fabled structure of the poet, only a wreath of laurel to bind the brows of the victor. Yet though replete with gorgeous materials both for history and fiction, and stored not only with the recondite lore of Asia and Egypt, but with the borrowed treasures of ancient Greece, (long known to Christendom only by versions through an Arabic medium,) the language and literature of this marvellous people, and even their history, except so far as it related to their never-ceasing warfare with their Christian foes, remained, up to the middle of the last century, a sealed book to their Spanish successors. Coming into possession, like the Israelites of old, "of a land for which they did not labour, of cities which they built not, of vineyards and olive-yards which they planted not," the Spaniards not merely contemned, but persecuted with the fiercest bigotry, all that was left in the peninsula of the genius and learning of their predecessors. Eighty thousand volumes were publicly burned in one fatal auto-da-fé at Granada by order of Cardinal Ximenes, in whom the literature of his own language yet found a munificent patron; and so meritorious, did the deed appear in the eyes of his contemporaries, that the number has been magnified to an incredible amount by his biographers, in their zeal for the renown of their hero! So complete was the destruction or deportation4 of the seventy public libraries, which, a century and a half before the subjugation of the Moors, were open in different cities of Spain, that the valuable collection now in the Escurial owes its origin to the accidental capture, early in the seventeenth century, of three ships laden with books belonging to Muley Zidan, emperor of Morocco—and even of this casual prize so little was the value appreciated, that it was not till more than a hundred years later, and after three-fourths of the books had been consumed by fire in 1671, that the learned and diligent Casiri was commissioned to make a catalogue of the remainder. The result was the well-known Bibliotheca Arabico-Hispana Escurialensis, which appeared in 1760-70; and which, in the words of the present learned translator, "though hasty and superficial, and containing frequent unaccountable blunders, must, with all its imperfections, ever be valuable as affording palpable proof of the literary cultivation of the Spanish Arabs, and as containing the first glimpses of historical truth." Up to this time the only authority on Spanish history purporting to be drawn from Mohammedan sources, was the work of a Morisco named Miguel de Luna, written by command of the Inquisition; which was first printed at Granada in 1592, and has passed through many editions. Its value may be estimated from its placing the Mohammedan conquest of Spain in the time of Yakub Al-mansor, the actual date of whose reign was from A.D. 1184 to 1199; insomuch that Señor de Gayangos suggests, as a possible explanation of its glaring inaccuracies, that it was the writer's intention to hoax his employers. Casiri had, however, opened the door for further researches; and he was followed in the same path by Don Faustino de Borbon, whose works, valuable rather from the erudition which they display than from their judgment or critical acumen, have now become extremely scarce—and next by Don Antonio José Condé, one of the most zealous and laborious, if not the most accurate, of Spanish orientalists. His "History of the Domination of the Arabs and Moors in Spain," has been generally regarded as of high authority, and is in truth the first work on the subject drawn wholly from Arab sources; but it receives summary condemnation from Señor de Gayangos, for "the uncouth arrangement of the materials, the entire want of critical or explanatory notes, the unaccountable neglect to cite authorities, the numerous repetitions, blunders, and contradictions." These charges are certainly not without foundation; but they are in some measure accounted for by the trouble and penury in which the author's last years were spent, and the unfinished state in which the work was left at his death in 1820.

An authentic and comprehensive view of the Arab period, as described by their own writers, was therefore still a desideratum in European literature, which the publication before us may be considered as the first step towards supplying. The work of Al-Makkari, which has been taken as a text-book, is not so much an original history as a collection of extracts, sometimes abridged, and sometimes transcribed in full, from more ancient historians; and frequently giving two or three versions of the same event from different authorities—so that, though it can claim but little merit as a composition, it is of extreme value as a repository of fragments of authors in many cases now lost; and further, as the only "uninterrupted narrative of the conquests, wars, and settlements of the Spanish Moslems, from their first invasion of the Peninsula to their final expulsion." In the arrangement of his materials, the translator has departed considerably, and with advantage, from the original; giving the historical books in the form of a continuous narrative, and omitting several sections relating to matters of little interest—while the deficiencies and omissions of the author are supplied by an appendix, containing, in addition to a valuable body of original notes, copious extracts from numerous unpublished Arabic MSS. relating to Spain, which afford ample proof of the extent and diligence of his researches among the Oriental treasures of Paris and London. To those in the Escurial, however, he was denied access during his labours—an almost incredible measure of illiberality, which, if he be correct in ascribing it to his known intention of publishing in England, "ill suits a country" (as he justly remarks in the preface) "which has lately seen its archives and monastic libraries reduced to cinders, and scattered or sold in foreign markets, without the least struggle to rescue or secure them."

Ahmed Al-Makkari, the author or compiler of the present work, derived his surname from a village near Telemsan called Makkarah, where his family had been established since the conquest of Africa by the Arabs. He was born at Telemsan some time in the latter half of the sixteenth century, and educated by his uncle, who held the office of Mufti in that city; but having quitted his native country in 1618 on a pilgrimage to Mekka, he married and settled in Cairo. During a visit to Damascus in 1628, he was received with high distinction by Ahmed Ibn Shahin Effendi, the director of the college of Jakmak in that city, and a distinguished patron of literature; at whose suggestion (he tells us) he undertook this work. His original purpose had been only to write the life of Abu Abdullah Lisanuddin, a celebrated historian and minister in Granada, better known to Oriental scholars as Ibnu'l-Khattib; but having completed this, the thought struck him of adding, as a second part, an historical account of the Moslems of Spain. He had formerly written an extensive and elaborate work on this subject, composed (to use his own words) "in such an elevated and pleasing style, that had it been publicly delivered by the common crier, it would have made even the stones deaf:—but, alas! the whole of this we had left in Maghreb (Morocco) with the rest of our library.... However, we have done our best to make the present work as useful and complete as possible." It was probably the last literary undertaking of his life; since he was on the point of quitting Cairo to fix his residence in Damascus, when he died of a fever in the second Jomada of A.H. 1041, (Jan. 1632,) leaving a high reputation as a traditionist and doctor of the Moslem law.

The introductory chapter gives a sketch of the various nations which inhabited Andalus or Spain before the Arab conquest, prefaced by extracts from numerous writers eulogistic of a country "whose excellences" (as Al-Makkari himself declares) "are such and so many that they cannot easily be contained in a book ... so that one of their wise men, who knew that the country had been called the bird's tail, owing to the supposed resemblance of the earth to a bird with extended wings, remarked that that bird was the peacock, the principal beauty of which was in the tail." These panegyrics are not in all cases exactly consistent; for while the famous geographer, Obeydullah Al-Bekri, "compares his native country to Syria for purity of air and water, to China for mines and precious stones, &c. &c., and to Al-Ahwaz (a district in Persia) for the magnitude of its snakes"—the Sheikh Ahmed Al-Razi (better known as the historian Razis) praises its comparative freedom from wild beasts and reptiles. The name Andalus is derived by some authors from a great grandson of Noah so named, who settled there soon after the deluge; but Al-Makkari rather inclines, with Ibn Khaldun and other writers, to deduce it from the Andalosh, (Vandals,) "a tribe of barbarians," who appear to be considered as the earliest inhabitants; but who, having incurred the divine wrath by their wickedness and idolatry, were all cut off by a terrible drought, which left the land for a hundred years an uninhabited desert. A colony then arrived from Africa, under a chief named Batrikus, eleven generations of whose descendants reigned for one hundred and fifty-seven years; after which they were all annihilated by the "barbarians of Rome, who invaded and conquered the country; and it was after their king Ishban, son of Titus, that Andalus was called Ishbaniah," (Hispania.) As Ishban is just after said to have "plundered and demolished Ilia, which is the same as Al-Kods the illustrious," (Jerusalem,) it is obvious that the name must be a corruption of Vespasian, who is thus made the son instead of the father of Titus. We are told that authors differ whether it was on this occasion, or at the former capture of Jerusalem by Bokht-Nasser, (Nebuchadnezzar,) at which a king of Spain named Berian was also present, that the table constructed by the genii for Solomon, and which Tarik afterwards found at Toledo, was transported to Spain—and Al-Makkari professes himself, as well he may, unable to reconcile the different accounts. Fifty-five kings descended from Ishban, whose race was dispossessed ("about the time of the Messiah, on whom be peace!") by a people called Bishtilikat, (Visigoths?) under a king called Talubush, (Ataulphus?) whom Al-Makkari holds to have been the same people as the "barbarians of Rome," though "there are not wanting authors who make the Goths and the Bishtilikat only one nation." After holding possession during the reigns of twenty-seven monarchs, they were in turn subdued by the Goths, whose royal residence was "Toleyalah, (Toledo,) though Isbiliah (Seville) continued to be the abode of the sciences." The Gothic kings are said to have been thirty-six;—but the only one particularized by name is "Khoshandinus, (Constantine,) who not only embraced Christianity himself, but called on his subjects to do the same, and is held by the Christians as the greatest king they ever had.... Several kings of his posterity reigned after him, till Andalus was finally subdued by the Arabs, by whose means God was pleased to make manifest the superiority of Islam over every other religion."

With the Arab, conquest the authentic history commences; and the accounts given from the Moslem writers of this memorable event, which first gave the followers of the Prophet a footing in Europe, differ in no material point from the eloquent narrative of Gibbon. Al-Makkari, however, does not fail to inform us, that predictions had been rife from long past ages, which foretold the invasion and conquest of the country by a fierce people from Africa; and potent were the spells and talismans constructed to ward off the danger, "by the Greek kings who reigned in old times." Several of these are described with due solemnity; and among them we find the tale of the visit paid by Roderic5 to the magic tower at Toledo, which has been rendered familiar by the pages of Scott and Southey. We shall not here recapitulate the well-known incidents of the wrongs and revenge of Count Yllan, or Julian, the first landing of Tarif at Tarifa, the second expedition sent by Musa under Tarik Ibn Zeyad, and the death or disappearance of the Gothic king on the fatal day of Guadalete.6 So complete was the discomfiture of the Christians, that the kingdom fell, without a second blow, before the victors of a single field; and was overrun with such rapidity, that from the inability of the conquerors to garrison the cities which surrendered, they were entrusted for the time to the guard of the Jews!—a singular circumstance, which, when coupled with the statement that many of the Berbers (of whom the invading army was almost wholly composed) were recent converts from Judaism,7 would apparently imply that the conquest was facilitated by a previous correspondence. The subjugation of the country was completed by the arrival of Musa himself, who reduced Seville and the other towns which still held out, and is even said to have crossed the Pyrenees and sacked Narbonne;8 but this is not mentioned by any Christian writer, and is referred by the translator to his invasion of Catalonia, which the Arabs considered as part of "the land of the Franks." After the first fury of conquest had subsided, the Christians who remained in their homes were permitted to live unmolested, on payment of the capitation-tax; but peculiar privileges were accorded to the Jews, and the hold of the Moslems on the country was strengthened by the vast influx of settlers, not only from Africa, but from Syria and Arabia, who were attracted by the reports of the riches and fertility of the new province. Nearly all the tribes of Arabia are enumerated by Al-Makkari as represented in Spain; and the feuds of the two great divisions, the Beni-Modhar9 or race of Adnan, and the Beni-Kahttan or Arabs of Yemen, gave rise to most of the civil wars which subsequently desolated Andalus.

The spoil of the vanquished kingdom was immense—the accumulation of long years of luxury and freedom from foreign invasion in a country which, both from the fertility of the soil and the abundance of the precious metals, was then probably the richest in Europe. Whatever degree of credit we may attach to the famous table of Solomon, "said by some to be of pure gold, and by others green emerald," and the gems and ornaments of which are described with full Oriental luxuriance, every account referring to the booty acquired in the principal cities, gives ample evidence of the riches and splendour of the Visigoths. "The plunder found at Toledo10 was beyond calculation. It was common for the lowest men in the army to find magnificent gold chains, and long strings of pearls and rubies. Among other precious objects were found 170 diadems of the purest red gold, set with every sort of precious stone; several measures full of emeralds, rubies, and other gems; and an immense number of gold and silver vases. Such was the eagerness for plunder, and the ignorance of some, especially the Berbers, that when two or more of this nation fell upon an article which they could not conveniently divide, they would cut it in pieces, whatever the material might be, and share it among them." Some of the victorious army seized some ships in the eastern ports, and set sail for their homes with their plunder; but they were speedily overtaken by a tremendous storm, and all perished in the waves—a manifest token, we are given to understand, of the Divine vengeance for the abandonment of the holy warfare under the banners of Islam.

Musa was on his march into Galicia to crush the last embers of national resistance, when his progress was checked by a peremptory summons from the Khalif, to answer at Damascus the charges forwarded against him by Tarik, whom he had unjustly disgraced and punished. Being convicted of falsehood, on the production by Tarik of the missing foot of the table of Solomon, the merit of finding which had been claimed by Musa, he was tortured and deprived of his riches; and the head of his gallant son Abdulaziz, whom he had left in command in Spain, was shown to him in public by the Khalif Soliman, the successor of Walid, with the cruel demand if he knew whose it was. "I do," was the father's reply: "it is the head of one who fasted and prayed; may the curse of Allah fall on it if he who slew him is a better man than he!" But though Musa was thus arrested in the last stage of his conquering career, so complete was the prostration of the Christians, that the viceroys who succeeded Abdulaziz, overlooking or disregarding this yet unsubdued corner of Spain, at once poured their forces across the Pyrenees, seeking new fields of conquest and glory in the countries of the Franks. But the antagonists whom they here encountered, unlike the luxurious Goths of Spain, still preserved the barbarian valour which they had brought from their German forests. And As-Samh, (the Zama of the Christian writers,) the first Saracen general who obtained a footing in France, "fell a martyr to the faith," with nearly his whole army, in a battle with Eudo, Duke of Aquitaine, before Toulouse, May 10, A.D. 721. But the fiery zeal of the Moslems was only stimulated by this reverse. In the course of the ten following years, their dominion was established as far as the Rhone and Garonne; till, in 732, the torrent of invasion, headed by the Wali Abdurrahman, burst into the heart of the country; and the battle, decisive of the destinies of France, and perhaps of Europe, was fought between Tours and Poitiers, in October of that year, (Ramadhan, A.H. 114.) Few details are given by the Arab writers of the seven days' conflict, in which the ranks of the Moslems were shattered by the iron arm of Charles Martel; "and the army of Abdurrahman was cut to pieces at a spot called Balatt-ush-Shohadá, (the Pavement of the Martyrs,) he himself being in the number of the slain." Some confusion here appears, as the same epithet had been applied to the former battle near Toulouse; but this "disastrous day" of Tours virtually extinguished the schemes of Arab conquest in France, though it was not till many years later that they were completely dislodged from Narbonne, and their other acquisitions between the Garrone and the Pyrenees.

Meanwhile the Christian remnant, left unmolested in the Asturian and Galician mountains, gradually recovered courage: and in 717-18, "a despicable barbarian," (as he is termed by Ibn Hayyan, a writer often cited by Al-Makkari,) "named Belay, (Pelayo or Pelagius,) rose in Galicia; and from that moment the Christians began to resist the Moslems, and to defend their wives and daughters; for till then they had not shown the least inclination to do so." "Would to God," piously subjoins Al-Makkari, "that the Moslems had then extinguished at once the sparkles of a fire destined to consume their whole dominion in those parts! But they said—'What are thirty barbarians, perched on a rock? they must inevitably die!'" The spark, which contained the germ of the future independence of Spain, was thus suffered to remain and spread, while the swords of the Moslems were occupied in France; and its growth was further favoured by the anarchy and civil dissensions which broke out among the conquerors. While the leaders of the different Arab factions contested, sword in hand, the viceroyalty of Spain, the Berbers (whose conversion to Islam was apparently yet but imperfect) rose in furious revolt both in Spain and Africa, and were only overpowered by a fresh army sent by the Khalif Hisham from Syria. But the arrival of these reinforcements added new fuel to the old feuds of the Beni-Modhar, and the Yemenis or Beni-Kahttan; and a desperate civil war raged till 746, when the Khalif's lieutenant, the Emir Abu'l-Khattar, who supported the Yemenis, was killed in a pitched battle fought near Cordova. The leader of the victorious tribe, Yusuf Al-Fehri,11 now assumed supreme power, which he exercised nearly ten years as an independent ruler, without reference to the court of Damascus. The state of affairs in the East, indeed, left little leisure to the Umeyyan khalifs to attend to the regulation of a remote province. Their throne was already tottering before the arms and intrigues of the Abbasides, whose black banners, under the guidance of the formidable Abu-Moslem, were even now bearing down from Khorassan upon Syria. The unpopular cause of the Beni-Umeyyah, who were detested for the murder of the grandsons of the Prophet under the second of their line, was lost in a single battle; and the death of Merwan, the last khalif of the race, was followed by the unsparing proscription of the whole family. "Every where they were seized and put to death without mercy; and few escaped the search made by the emissaries of As-Seffah, (the bloodshedder, the surname of the first Abbaside khalif,) in every province of the empire."