Various

Adventures in Many Lands

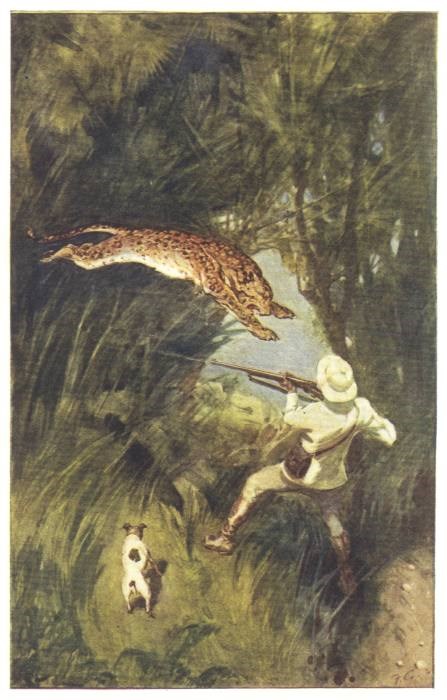

THE WOUNDED ANIMAL SUDDENLY SPRANG OUT AT ME.

I

A TERRIBLE ADVENTURE WITH HYENAS

There are many mighty hunters, and most of them can tell of many very thrilling adventures personally undergone with wild beasts; but probably none of them ever went through an experience equalling that which Arthur Spencer, the famous trapper, suffered in the wilds of Africa.

As the right-hand man of Carl Hagenbach, the great Hamburg dealer in wild animals, for whom Spencer trapped some of the finest and rarest beasts ever seen in captivity, thrilling adventures were everyday occurrences to him. The trapper's life is infinitely more exciting and dangerous than the hunter's, inasmuch as the latter hunts to kill, while the trapper hunts to capture, and the relative risks are not, therefore, comparable; but Spencer's adventure with the "scavenger of the wilds," as the spotted hyena is sometimes aptly called, was something so terrible that even he could not recollect it without shuddering.

He was out with his party on an extended trapping expedition, and one day he chanced to get separated from his followers; and, partly overcome by the intense heat and his fatigue, he lay down and fell asleep—about the most dangerous thing a solitary traveller in the interior of Africa can do. Some hours later, when the scorching sun was beginning to settle down in the west, he was aroused by the sound of laughter not far away.

For the moment he thought his followers had found him, and were amused to find him taking his difficulties so comfortably; but hearing the laugh repeated he realised at once that no human being ever gave utterance to quite such a sound; in fact, his trained ear told him it was the cry of the spotted hyena. Now thoroughly awake, he sat up and saw a couple of the ugly brutes about fifty yards away on his left. They were sniffing at the air, and calling. He knew that they had scented him, but had not yet perceived him.

In such a position, as sure a shot and one so well armed as Spencer was, a man who knew less about wild animals and their habits would doubtless have sent the two brutes to earth in double quick time, and thus destroyed himself. But Spencer very well knew from their manner that they were but the advance-guard of a pack. The appearance of the pack, numbering about one hundred, coincided with his thought. To tackle the whole party was, of course, utterly out of the question; to escape by flight was equally out of the question, for hyenas are remarkably fast travellers.

His only possible chance of escape, therefore, was to hoodwink them, if he could, by feigning to be dead; for it is a characteristic of the hyena to reject flesh that is not putrid. He threw himself down again, and remained motionless, hoping the beasts would think him, though dead, yet unfit for food. It was an off-chance, and he well knew it; but there was nothing else to be done.

In a couple of seconds the advance-guard saw him, and, calling to their fellows, rushed to him. The pack answered the cry and instantly followed. Spencer felt the brutes running over him, felt their foul breath on his neck, as they sniffed at him, snapping, snarling, laughing; but he did not move. One of them took a critical bite at his arm; but he did not stir. They seemed nonplussed. Another tried the condition of his leg, while many of them pulled at his clothes, as if in impotent rage at finding him so fresh. But he did not move; in an agony of suspense he waited motionless.

Presently, to his amazement, he was lifted up by two hyenas, which fixed their teeth in his ankle and his wrist, and, accompanied by the rest, his bearers set off with him swinging between them, sometimes fairly carrying him, sometimes simply dragging him, now and again dropping him for a moment to refix their teeth more firmly in his flesh. Believing him to be dead, they were conveying him to their retreat, there to devour him when he was in a fit condition. He fully realised this, but he was powerless to defend himself from such a fate.

How far they carried him Spencer could not tell, for from the pain he was suffering from his wounds, and the dreadful strain of being carried in such a manner, he fell into semi-consciousness from time to time; but the distance must have been considerable, for night was over the land and the sky sparkling with stars before the beasts finally halted; and then they dropped him in what he knew, by the horrible and overpowering smell peculiar to hyenas, was the cavern home of the pack. Here he lay throughout the awful night, surrounded by his captors, suffering acutely from his injuries, thirst, and the vile smell of the place.

When morning broke he found that the pack had already gone out in search of more ready food, leaving him in charge of two immense brutes, which watched him narrowly all through the day; for, unarmed as he was, and exhausted, he knew it would be suicide to attempt to tackle his janitors. He could only wait on chance. Once or twice during the day the beasts tried him with their teeth, giving unmistakable signs of disgust at the poor progress he was making. At nightfall they tried him again, and, being apparently hungry, one of them deserted its post and went off, like the others, in search of food.

This gave the wretched man a glimmering of hope, for he knew that the hyena dislikes its own company, and that the remaining beast would certainly desert if the pack remained away long enough. But for hour after hour the animal stayed on duty, never going farther than the mouth of the cave. When the second morning broke, however, the hyena grew very restless, going out and remaining away for brief periods. But it always returned, and every time it did so Spencer naturally imagined it had seen the pack returning, and that the worst was in store for him. But at length, about noon, the brute went out and did not come back.

Spencer waited and waited, fearing to move lest the creature should only be outside, fearing to tarry lest he should miss his only chance of escaping. After about an hour of this suspense he crept to the mouth of the cave. No living creature was within sight. He got upon his faltering feet, and hurried away as fast as his weakness would permit; but his condition was so deplorable that he had not covered a mile when he collapsed in a faint.

Fortune, however, favours the brave; and although he fell where he might easily have remained for years without being discovered, he was found the same day by a party of Boers, who dressed his wounds, gave him food and drink (which he had not touched for two days), and helped him by easy stages to the coast.

Being a man of iron constitution, he made a rapid and complete recovery, but his wrist, ankle, arms, and thigh still bear the marks of the hideous teeth which, but for his marvellous strength of will, would have torn him, living, to shreds.

II

THE VEGA VERDE MINE

Jim Cayley clambered over the refuse-heaps of the mine, rejoicing in a tremendous appetite which he was soon to have the pleasure of satisfying.

There was also something else.

Little Toro, the kiddy from Cuba—"Somebody's orphan," the Spaniards of the mine called him, with a likely hit at the truth—little Toro had been to the Lago Frio with Jim, to see that he didn't drown of cramp or get eaten by one of the mammoth trout, and had hinted at dark doings to be wrought that very day, at closing time or thereabouts.

Hitherto, Jim had not quite justified his presence at the Vega Verde mine, some four thousand feet above sea-level in these wilds of Asturias. To be sure, he was there for his health. But Mr. Summerfield, the other engineer in partnership with Alfred Cayley, Jim's brother, had, in a thoughtless moment, termed Jim "an idle young dog," and the phrase had stuck. Jim hadn't liked it, and tried to say so. Unfortunately, he stammered, and Don Ferdinando (Mr. Summerfield) had laughed and gone off, saying he couldn't wait.

Now it was Jim's chance. He felt that this was so, and he rejoiced in the sensation as well as in his appetite and the thought of the excellent soup, omelette, cutlets, and other things which it was Mrs. Jumbo's privilege to be serving to the three Englishmen (reckoning Jim in the three) at half-past one o'clock precisely.

Toro had made a great fuss about his news. He was drying Jim at the time, and Jim was saying that he didn't suppose any other English fellow of fifteen had had such a splendid bathe. There were snow-peaks in the distance, slowly melting into that lake, which well deserved its name of "Cold."

"Don Jimmy," said young Toro, pausing with the towel, "what do you think?"

"Think?" said Jimmy. "That I—I—I—I'll punch your black head for you if you don't finish this j—j—j—job, and b—b—b—be quick about it."

He wasn't really fierce with the Cuban kiddy. The Cuban kiddy himself knew that, and grinned as he made for Jim's shoulder.

"Yes, Don Jimmy," he said; "don't you worry about that. But I'm telling you a straight secret this time—no figs about it."

Toro had picked up some peculiar English by association with the Americans who had swamped his native land after the great war. Still, it was quite understandable English.

"A s—s—s—straight secret! Then j—j—just out with it, or I'll p—p—p—punch your head for that as well," said Jimmy, rushing his words.

He often achieved remarkable victories over his affliction by rushing his words. He could do this best with his inferiors, when he hadn't to trouble to think what words he ought to use. At school he made howling mistakes just because of his respectful regard for the masters and that sort of thing. They didn't seem to see how he suffered in his kindly consideration of them.

It was same with Don Ferdinando. Mr. Summerfield was a very great engineering swell when he was at home in London. Jimmy couldn't help feeling rather awed by him. And so his stammering to Don Ferdinando was something "so utterly utter" (as his brother said) that no fellow could listen to it without manifest pain, mirth, or impatience. In Don Ferdinando's case, it was generally impatience. His time was worth pounds a minute or so.

"All right," said Toro. "And my throat ain't drier than your back now, Don Jimmy; so you can put your clothes on and listen. They're going to bust the mine this afternoon—that's what they're going to do; and they'd knife me if they knew I was letting on."

"What?" cried Jimmy.

"It's a fact," said Toro, dropping the towel and feeling for a cigarette. "They're all so mighty well sure they won't be let go down to Bavaro for the Saint Gavino kick-up to-morrow that they've settled to do that. If there ain't no portering to do, they'll be let go. That's how they look at it. They don't care, not a peseta between 'em, how much it costs the company to get the machine put right again; not them skunks don't. What they want is to have a twelve-hour go at the wine in the valley. You won't tell of me, Don Jimmy?"

"S—s—snakes!" said Jimmy.

Then he had started to run from the Lago Frio, with his coat on his arm. Dressing was a quick job in those wilds, where at midday in summer one didn't want much clothing.

"No, I won't let on!" he had cried back over his shoulder.

Toro, the Cuban kiddy, sat down on the margin of the cold blue lake and finished his cigarette reflectively. White folks, especially white English-speaking ones, were rather unsatisfactory. He liked them, because as a rule he could trust them. But Don Jimmy needn't have hurried away like that. He, Toro, hoped to have had licence to draw his pay for fully another hour's enjoyable idleness. As things were, however, Don Alonso, the foreman, would be sure to be down on him if he were two minutes after Don Jimmy among the red-earth heaps and the galvanised shanties of the calamine mine on its perch eight hundred feet sheer above the Vega Verde.

Jim Cayley was a few moments late for the soup after all.

"I s—s—say!" he began, as he bounced into the room.

"Say nothing, my lad!" exclaimed Don Alfredo, looking up from his newspaper.

[Words missing in original] mail had just arrived—an eight-mile climb, made daily, both ways, by one of the gang.

Mrs. Jumbo, the moustached old Spanish lady who looked after the house, put his soup before Jimmy.

"Eat, my dear," she said in Spanish, caressing his damp hair—one of her many amiable yet detested little tricks, to signify her admiration of Jim's fresh complexion and general style of beauty.

"But it's—it's—it's most imp—p—p–"

Don Ferdinando set down his spoon. He also let the highly grave letter from London which he was reading slip into his soup.

"I tell you what, Cayley," he said, "if you don't crush this young brother of yours, I will. This is a matter of life or death, and I must have a clear head to think it out."

"I was only saying," cried Jim desperately. But his brother stopped him.

"Hold your tongue, Jim," he said. "We've worry enough to go on with just at present. I mean it, my lad. If you've anything important to proclaim, leave it to me to give you the tip when to splutter at it. I'm solemn."

When Don Alfredo said he was "solemn," it often meant that he was on the edge of a most unbrotherly rage. And so Jim concentrated upon his dinner. He made wry faces at Mrs. Jumbo and her strokings, and even found fault with the soup when she asked him sweetly if it were not excellent. All this to relieve his feelings.

The two engineers left Jim to finish his dinner by himself. Jim's renewed effort of "I say, Alf!" was quenched by the upraised hands of both engineers.

Outside they were met by Don Alonso, the foreman, a very smart and go-ahead fellow indeed, considering that he was a Spaniard.

"They'll strike, señores!" said Don Alonso, with a shrug. "It can't be helped, I'm afraid. It's all Domecq's doing, the scoundrel! Why didn't you dismiss him, Don Alfredo, after that affair of Moreno's death? There's not a doubt he killed Moreno, and he hasn't a spark of gratitude or goodness in his nature."

"He's a capable hand," said Alfred Cayley.

"Too much so, by half," said Don Ferdinando. "If he were off the mine, Elgos, we should run smoothly, eh?"

"I'll answer for that, señor," replied the foreman. "As it is, he plays his cards against mine. His influence is extraordinary. There'll not be a man here to-morrow; Saint Gavino will have all their time and money."

"You don't expect any active mischief, I hope?" suggested Don Ferdinando.

The foreman thought not. He had heard no word of any.

"Very well, then. I'll settle Domecq straight off," said Don Ferdinando.

He returned to the house and pocketed his revolver. They had to be prepared for all manner of emergencies in these wilds of Asturias, especially on the eves and morrows of Saints' days. But it didn't at all follow that because Don Ferdinando pocketed his shooter he was likely to be called upon to use it.

The three were separating after this when a lad in a blue cotton jacket rose lazily from behind a heap of calamine just to the rear of them, and swung off towards the machinery on the edge of the precipice.

"Pedro!" called the foreman, and, returning, the lad was asked if he had been listening.

He vowed that such a thought had not entered his head. He had been asleep; that was all.

"Very good!" said the foreman. "You may go, and it's fifty cents off your wage list that your sleep out of season has cost you."

Discipline at the mine had to be of the strictest. Any laxity, and the laziest man was bound to start an epidemic of laziness.

Don Ferdinando set off for the Vega, eight hundred feet sheer below the mine. It was a ticklish zigzag, just to the left of the transporting machinery, with twenty places in which a slip would mean death.

Domecq was working down below, lading the stuff into bullock-carts.

Alfred Cayley disappeared into one of the upper galleries, to see how they were panning out.

The snow mountains and the afternoon sun looked down upon a very pleasing scene of industry—blue-jacketed workers and heaps of ore; and upon Jim Cayley also, who had enjoyed his dinner so thoroughly that he didn't think so much as before about his rejected information.

But now again the Cuban kiddy drifted towards him, making for the zigzag.

Jim hailed him.

"Can't stop, Don Jimmy!" said Toro. But when he was some yards down, he beckoned to Jim, who quickly joined him.

They conferred on the edge of a ghastly precipice.

"I'm off down to tell Domecq that it's going to be done at two-thirty prompt," said Toro.

"What's going to be d—done?" asked Jimmy.

"What I told you about. They've cut the 'phone down to the 'llano' as a start. But that's nothing. You just go and squat by the engine and see what happens. Guess they'll not mind you."

To tell the truth, Jim was a trifle dazed. He didn't grapple the ins and outs of a conspiracy of Spanish miners just for the sake of a holiday. And as Toro couldn't wait (it was close on half-past two), Jim thought he might as well act on his advice. He liked to see the big buckets of ore swinging off into space from the mine level and making their fearful journey at a thrilling angle, down, down until, as mere specks, they reached the transport and washing department of the mine in the Vega. Two empty buckets came up as two full ones went down, travelling with a certain sublimity along the double rope of woven wire.

Jim sat down at a distance. He saw one cargo get right off—no more.

Then he noticed that the men engaged at the engine were confabulating. He saw a gleam of instruments. Also he saw another full bucket hitched on and sent down at the run. And then he saw the men furtively at work at something.

Suddenly the cable snapped, flew out, yards high!

Jim saw this—and something more. Looking instantly towards the Vega he saw the return bucket, hundreds of feet above the level, toss a somersault as it was freed of its tension and—this was horrible!—pitch a man head-foremost into the air.

He cried out at the sight, and so did the rascals who had done their rattening for a comparatively innocent purpose.

But when he and a dozen others had made the desperate descent of the zigzag, they found that the dead man was Domecq. Even the miners had no love for this arch-troubler, and, in trying to avoid Don Ferdinando, the sight of whom, coming down the track, had warned him of danger, Domecq had done the mine the best turn possible.

Toro's own warning was of course much too late.

The tragedy had a great effect. Saint Gavino was neglected after all, and it was in very humble spirits that the ringleaders of the plot confessed their sins and agreed to suffer the consequences.

Jim by-and-by tried to tell his brother and Don Ferdinando that if only they had listened to him at dinner the "accident" might not have happened. But he stammered so much again (Don Ferdinando was as stern as a headmaster) that he shut up.

"It's—it's—nothing particu—ticu—ticular, Mr. Summerfield!" he explained.

Don Ferdinando was anything but depressed about Domecq's death; and Jim didn't want to damp his spirits. Of course, if Domecq had really killed another fellow only a few weeks ago, as was rumoured, he deserved the fate that had overtaken him.

III

A VERY NARROW SHAVE

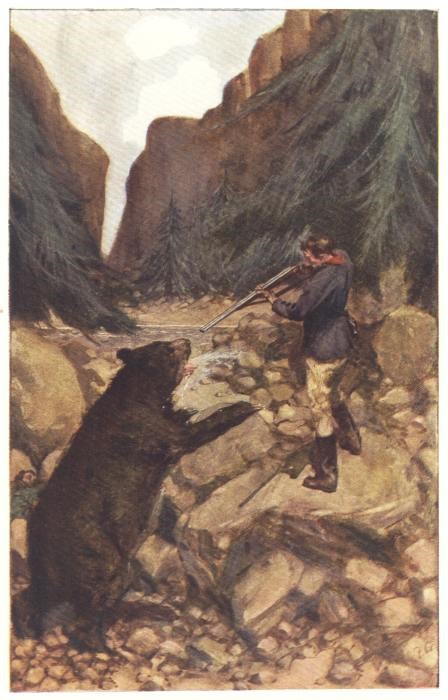

One winter's day in San Francisco my friend Halley, an enthusiastic shot who had killed bears in India, came to me and said, "Let's go south. I'm tired of towns. Let's go south and have some real tip-top shooting."

In the matter of sport, California in those days—thirty years ago—differed widely from the California of to-day. Then, the sage brush of the foot-hills teemed with quail, and swans, geese, duck (canvas-back, mallard, teal, widgeon, and many other varieties) literally filled the lagoons and reed-beds, giving magnificent shooting as they flew in countless strings to and fro between the sea and the fresh water; whilst, farther inland, snipe were to be had in the swamps almost "for the asking." On the plains were antelope, and in the hills and in the Sierra Nevadas, deer and bears, both cinnamon and grizzly. Verily a sportsman's paradise!

The next day saw us on board the little Arizona, bound for San Pedro, a forty-hours' trip down the coast. We took with us only shot-guns, meaning to try for nothing but small game. At San Pedro, the port for Los Angeles (Puebla de los Angeles, the "Town of the Angels"), we landed, and after a few days' camping by some lagoons near the sea, where we shot more duck than could easily be disposed of, we made our way to that little old Spanish settlement, where we hired a horse and buggy to take us inland.

Our first stopping-place was at a sheep-ranche, about fifty miles from Los Angeles, a very beautiful property, well grassed and watered, and consisting chiefly of great plains through which flowed a crystal-clear river, and surrounded on very side by the most picturesque of hills, 1,000 to 1,500 feet in height.

The ranche was owned by a Scotsman, and his "weather-board" house was new and comfortable, but we found ourselves at the mercy of the most conservative of Chinese cooks, whom no blandishments could induce to give us at our meals any of the duck or snipe we shot, but who stuck with unwearying persistency to boiled pork and beans. And on boiled pork and beans he rang the changes, morning, noon, and night; that is to say, sometimes it was hot, and sometimes it was cold, but it was ever boiled pork and beans. At its best it is not a diet to dream about (though I found that a good deal of dreaming could be done upon it), and as we fancied, after a few days, that any attraction which it might originally have possessed had quite faded and died, we resolved to push on elsewhere.

The following night we reached a little place at the foot of the higher mountains called Temescal, a very diminutive place, consisting, indeed, of but one small house. The surroundings, however, were very beautiful, and the presence of a hot sulphur-spring, bubbling up in the scrub not one hundred yards from the house, and making a most inviting natural bath, coupled with the favourable reports of game of all kinds to be got, induced us to stop. And life was very pleasant there in the crisp dry air, for the quail shooting was good, the scenery and weather perfect, everything fresh and green and newly washed by a two days' rain, the food well cooked, and, nightly, after our day's shooting, we rolled into the sulphur-spring and luxuriated in the hot water.

But Halley's soul began to pine for higher things, for bigger game than quail and duck. "Look here," he said to me one day, "this is all very well, you know, but why shouldn't we go after the deer amongst the hills? We've got some cartridges loaded with buckshot. And, my word! we might get a grizzly."

"All right," I said, "I'm on, as far as deer are concerned, but hang your grizzlies. I'm not going to tackle them with a shot-gun."

So it was arranged that next morning, before daylight, we should go, with a boy to guide us, up one of the numerous cañons in the mountains, to a place where we were assured deer came down to drink.

It was a cold, clear, frosty morning when we started, the stars throbbing and winking as they seem to do only during frost, and we toiled, not particularly gaily, up the bed of a creek, stumbling in the darkness and barking our shins over more boulders and big stones than one would have believed existed in all creation. Just before dawn, when the grey light was beginning to show us more clearly where we were going, we saw in the sand of the creek fresh tracks of a large bear, the water only then beginning to ooze into the prints left by his great feet, and I can hardly say that I gazed on them with the amount of enthusiasm that Halley professed to feel.

But bear was not in our contract, and we hurried on another half-mile or so, for already we were late if we meant to get the deer as they came to drink; and presently, on coming to a likely spot, where the cañon forked, Halley said, "This looks good enough. I'll stop here and send the boy back; you can go up the fork about half a mile and try there."

And on I went, at last squatting down to wait behind a clump of manzanita scrub, close to a small pool where the creek widened.

It was as gloomy and impressive a spot as one could find anywhere out of a picture by Doré. The sombre pines crowded in on the little stream, elbowing and whispering, leaving overhead but a gap of clear sky; on either hand the rugged sides of the cañon sloped steeply up amongst the timber and thick undergrowth, and never the note of a bird broke a silence which seemed only to be emphasised by the faint sough of the wind in the tree tops. Minute dragged into minute, yet no deer came stealing down to drink, and rapidly the stillness and heart-chilling gloom were getting on my nerves; when, far up the steep side of the cañon opposite to me there came a faint sound, and a small stone trickled hurriedly down into the water.

"At last!" I thought. "At last!" And with a thumping heart and eager eye I crouched forward, ready to fire, yet feeling somewhat of a sneak and a coward at the thought that the poor beast had no chance of escape. Lower and nearer came the sound of the something still to me invisible, but the sound, slight though it was, gave, somehow, the impression of bulk, and the strange, subdued, half-grunting snuffle was puzzling to senses on the alert for deer. Lower and nearer, and then—out into the open by the shallow water he strolled—no deer, but a great grizzly.

My first instinct was to fire and "chance it," but then in stepped discretion (funk, if you will), and I remembered that at fifteen or twenty yards buckshot would serve no end but to wound and rouse to fury such an animal as a grizzly, who, perhaps of all wild beasts, is the most tenacious of life; and I remembered, too, tales told by Californians of death, or ghastly wounds, inflicted by grizzlies.

My finger left the trigger, and I sat down—discreetly, and with no unnecessary noise. He was not in a hurry, but rooted about sedately amongst the undergrowth, now and again throwing up his muzzle and sniffing the air in a way that made me not unthankful that the faint breeze blew from him to me, and not in the contrary direction.

In due time—an age it seemed—after a false start or two, he went off up stream, and I, wisely concluding that this particular spot was, for the present, an unlikely one for deer, followed his example, and rejoined Halley, who was patiently waiting where we had parted.

"I've just seen a grizzly, Halley," I said.

"Have you?" he almost yelled in his excitement. "Come on! We'll get him."

"I don't think I want any more of him," said I, with becoming modesty. "I'm going to see if I can't stalk a deer amongst the hills. They're more in my line, I think."

Halley looked at me—pity, a rather galling pity, in his eye—and, turning, went off alone after the bear, muttering to himself, whilst I kept on my course downstream, over the boulders, certain in my own mind that no more would be seen of that bear, and keeping a sharp look-out on the surrounding country in case any deer should show themselves.

I had gone barely half a mile when, on the spur of a hill, a long way off, I spotted a couple of deer browsing on the short grass, and I was on the point of starting what would have been a long and difficult, but very pretty, stalk when I heard a noise behind me.

Looking back, I saw Halley flying from boulder to boulder, travelling as if to "make time" were the one and only object of his life—running after a fashion that a man does but seldom.

I waited till he was close to me, till his wild eyes and gasping mouth bred in me some of his panic, and then, after a hurried glance up the creek, I, too, turned and fled for my life.

For there, lumbering and rolling heavily along, came the bear, gaining at every stride, though evidently sorely hurt in one shoulder. But my flight ended almost as it began, for a boulder, more rugged than its fellows, caught my toe and sent me sprawling, gun and cartridge-bag and self in an evil downfall.

I picked myself up and grabbed for my gun, and, even as I got to my feet, the racing Halley tripped and rolled over like a shot rabbit. It was too late for flight now, and I jumped for the nearest big boulder, scrambling up and facing round just in time to see the bear, fury in his eyes, raise his huge bulk and close with Halley, who was struggling to his feet. Before I could fire down came the great paw, and poor Halley collapsed, his head, mercifully, untouched, but the bone of the upper arm showing through the torn cloth and streaming blood.

I fired ere the brute could damage him further, fired my second barrel almost with the first, but with no apparent result except to rouse the animal to yet greater fury, and he turned, wild with rage, and came at me. A miserably insignificant pebble my boulder seemed then, and I remember vaguely and hopelessly wondering why I hadn't climbed a tree. But there was small time for speculation, as I hurriedly, and with hands that seemed to be "all thumbs," tried to slip in a couple of fresh cartridges.

As is generally the case when one is in a tight place, one of the old cases jammed and would not come out—they had been refilled, and had, besides, been wet a few days before, and my hands were clumsy in my haste—and so, finally, I had to snap up the breech on but one fresh cartridge, throw up the gun, and fire, as the bear was within ten feet of me.

I fired, more by good luck, I think, than anything else, down his great, red, gaping mouth, and jumped for life as he crashed on to the rock where I had stood, crashed and lay, furiously struggling, the blood pouring from his mouth and throat, for the buckshot, at quarters so close, had inflicted a wound ten times more severe than would have been caused by a bullet.

I FIRED DOWN HIS GREAT, RED, GAPING MOUTH AND JUMPED FOR LIFE.

It was quite evident that the bear was done, but, for the sake of safety—it does not do to leave anything to chance with such an animal—I put two more shots into his head, and he ceased to struggle, a great shudder passed over his enormous bulk, the muscles relaxed, and he lay dead.