Самсон Хохотов

Formosa. Country of success

懷著極大的敬意, 向您推薦我的書。

略尽绵薄之力,

幫助國際友人更了解與認識台灣,

對台灣旅遊業的發展作出一點貢獻。

林巴虎

I dedicate this book to my friend Princess Michael of Kent, born Baroness Marie-Christine Anne Agnes Hedwig Ida von Reibnitz, who once helped me open a new page in my life.

Geography, Topography, Population and Language

Taiwan is a large island located in the Pacific Ocean near the eastern coast of mainland China. Since 1949, it has been functioning as an independent state, the Republic

of China. The coast of Taiwan is washed by the East China Sea to the North, the South China Sea and the Philippine Sea to the South and the Pacific Ocean to the East.

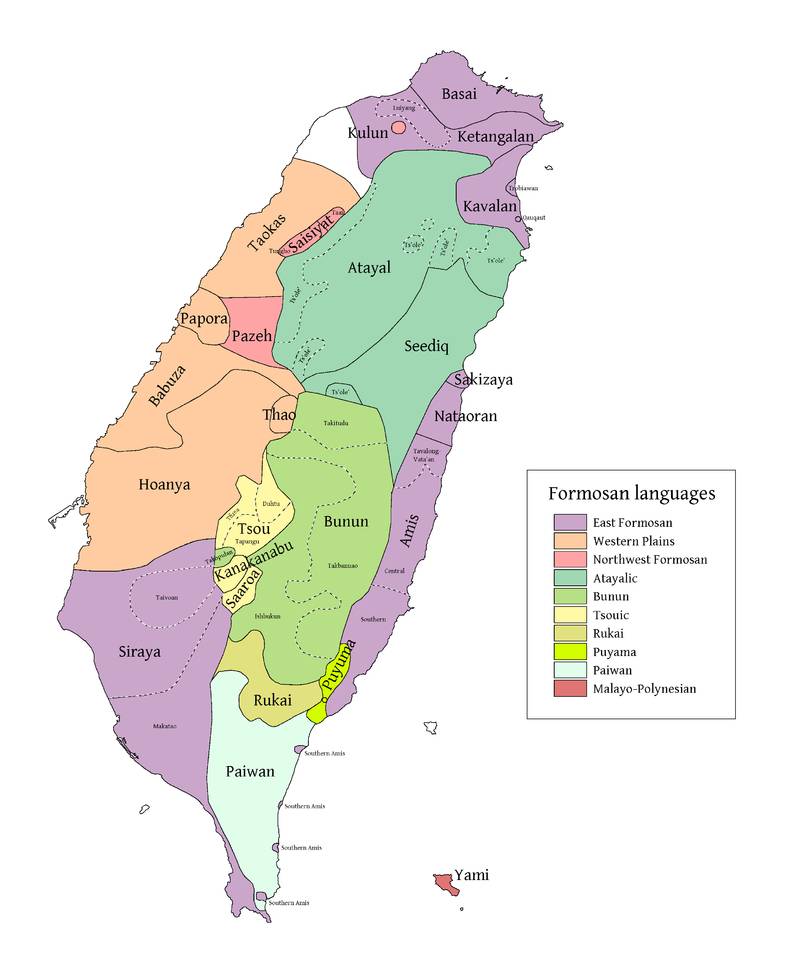

The island stretches for 394 km north to south, and is approximately 140 km across, giving an area of about 35,834 square kilometres. The length of the coastline is 1566 km. The eastern shores of the main island of Taiwan are steep, while in the west they are mostly flat with gently sloping plains. In the north, there are several (and, according to the latest updated information), dormant volcanoes. The Taiwan Mountains, covered with forests, stretch along the entire island. The highest of these is Mount Yushan at 3952m. In the west, there is a coastal plain and 90% of the island's population lives here. It is known that Aborigines lived in Taiwan about 10,000 years ago while, in contrast, the inhabitants of mainland China only began to settle in masse about 100 years ago. Today, about 10% of Taiwan residents speak the dialects of the Austronesian languages and these repre sent the indigenous population.

These aboriginal languages were once on the brink of extinction however, over the last 30 years or so, the authorities have been carefully preserving all ethnic groups of the population, actively helping them to develop the cultural heritage of their ancestors, and especially their languages.

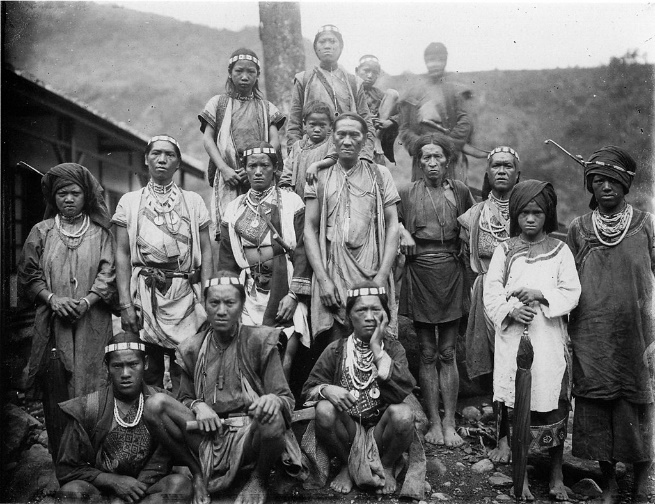

An example of this is the people of the eastern coast of Taiwan who are called the Gaoshan.

There was a time when only a few living native speakers remained amongst the Gaoshan however the creation of a special Center for the Support of Ethnic Cultures

in 2000 has led to a complete revival of the language and this, in turn, has made it possible to open several radio and TV channels transmitting in the local dialect. Nowadays residents who speak a language belonging to the Austronesian family can easily switch to more widely used dialects while still retaining

their own. The dialect of most Taiwanese is

known as Hokhlo, the modern name for which is now Taiwan Hua or Guo Yu.

The Taiwan Hua dialects have their origin from the Fujian Province of China where this language group is known as Minnan Hua or Tai Yu.

Although Guo Yu was adopted as the country’s official language, about 70 per cent of the island's population use Tai Yu which is mainly spoken in the family circle and it also remains the language of communication within the framework of the village and other social communities.

While Tai Yu has no official status it can widely be found on subways and advertisements in the capital as well as in some non-state newspapers, books, online publications and shop window inscriptions.

When it comes to written language the people of Taiwan use traditional Chinese characters in addition to a Zhu Yin

writing system developed by Western philologists and which is based on the Latin alphabet. There is also another language, that is very different from the usual Chinese. To

some, it may seem similar to the Cantonese dialect and there

are several million native speakers of this dialect of Chinese left.

It is called the Hakka language and its speakers belong to a Chinese clan group. This name is translated as "guest". The endurance and self-confidence of these people were shaped and further developed by their long travels and wanderings among hostile tribes back home in northern China. The proximity to Fujian ensured that many people from here, which has a considerable population of Hakka, migrated to Taiwan.

Until 1945, Japanese was the official language in Taiwan and taught in schools. But after the end of World War II in 1945, Guo Yu became the official language and began to be taught in schools. The hill tribes speak the Taiwanese languages of the Austronesian family and Guo Yu, while the lowland Taiwanese completely switched over to Guo Yu. The indigenous population of Taiwan of Austronesian origin includes the Aborigines, whose total number is about 550,000 people. Plains Aborigines can be found in the west and north of Taiwan, while Mountain Aborigines inhabit the central and southern parts of the island and the eastern plains.

These have mostly preserved their original culture and languages.

According to official data, plains tribes (from south to north)

:

Siraya

Mattauw

Soelangh

Baccloangh

Sinckan

Taivoan

Hoanya

Lioa

Arikun

Babuza

Papora

Pazeh

Taokas

Ketangalan (Luilan)

Basai

Kaukaut

Trobivan

Kavalan (Cabaran)

Hill tribes include (from north to

South):

Saysiyat

Atayal

Truku (Taroko or Sedek)

Thao

Tzou

Kanakhabu

Saaroa

Bunun

Rukai

Ami (Pantsakh)

Puyuma

Paiwan

Officially, Yami (Taoist) is also referred to as Gaoshan. Yami live on a small island of Lanyu South-East of Taiwan. They speak the Austronesian language Yami, which resembles the Filipino language, Tagalog.

History of settlement

The history of Taiwan, with the appearance of the first humans, goes back as far as the

Upper Paleolithic period.

In the Taiwan Strait, near the Pescadores Islands (the Penghu Islands), fishermen fished out the jaw of an ancient man who belonged to the species Homo erectus. The first humans appeared in Taiwan around 50,000 BC. Some scientists claim the Negro-Australoids to be the first settlers in Taiwan since the Paleolithic, regarding archaeological and

has disappeared over time. Almost simultaneously with the Negroids, the Indonesians settled in Taiwan. The  Austronesians are believed to have reached Taiwan, the Korean Peninsula, Northeast China and Japan by sea.

Austronesians are believed to have reached Taiwan, the Korean Peninsula, Northeast China and Japan by sea.

Scientists generally believe that Java and Sulawesi provided the principal source of Austronesian migration. Additionally, Oceania is another source of migration, as evidenced by the megaliths at the eastern coast of Taiwan and anthropological observations.

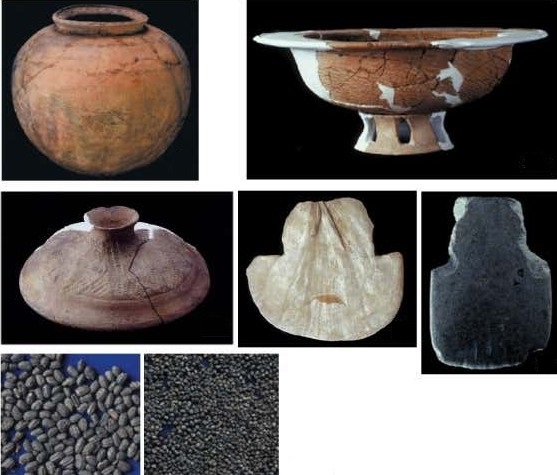

The resettlement was not simultaneous but occurred in waves throughout the Neolithic period, as evidenced by the Corded Ware finds. Recently, researchers have concluded that both processes took place in Taiwan migration and autochthonous development. The migrants had adapted to the new conditions, and their descendants became aborigines.

The earliest archaeological culture in Taiwan was the Changbin culture, named after the place of finds in the east of Taiwan. Sites of ancient Taiwanese have also been located in other locations in Taiwan, especially in Tainan County and in

the Taipei Basin. Most likely, they were representatives of the Australoid race and inhabited all of Southeast Asia between 10 and 45 thousand years ago.

It is Taiwan that is the ancestral home of the Austronesian languages. In around 8000 years B.C. and as evidenced by archaeological finds, Austronesian native-speakers initially migrated from the east coast of China to Taiwan.

Native speakers of these languages only later, according to the data of historical linguistics, began to migrate from the island of Taiwan by sea throughout Oceania. This migration is understood to have started about 6,000 years ago and occurred in several stages. Taiwan's Neolithic past is the Dabenken culture (2700-5000 BC).

The first Taiwanese crops were yams and taro. From the 2nd millennium B.C., the natives of Taiwan began to breed dogs and pigs. The oldest evidence of life in Taiwan is the skeleton of a young woman with a child in her arms found near the city of Taichung. Following scientific analysis, the age of the fossils is around 4800 years, and therefore they belong to the Neolithic era. The earliest mention of the island of Taiwan was in Chinese sources of the 3rd century BC. This information is, however, very scarce. The Chinese, being close neighbours, were in no hurry to colonize the island.

By the third century, when life on the island was relatively- well established, military expeditions by the Chinese began. Crafts had developed, and agricultural plants grew. The early Iron Age on the island, represented by the Jingpu culture, dates back to the 1st millennium BC.

Over time, the local ceramic pottery tradition disappeared. Local craftsmen learned how to make products from porcelain and metal. The Taiwanese achieved sophistication in the production of copper bells that scare away evil spirits.

And in the 1st millennium AD, iron knives and spearheads are already appearing. These items belong to the Nyaosun culture.

Production of plain red-brown ceramics (without ornaments) begins.

The development of navigation, characteristic of the rest of the Austronesians, fades into the background, while the development of the island is becoming the main priority in the life of the Taiwanese. Despite the difficulties, little by little the Taiwanese natives selflessly mastered even the remote mountainous regions.

The ancient Chinese chronicles Hou Han Shu and San Go Zhi contain the first mentions of an island called Yizhou (the island of the barbarians).

Since the Sui period (years 581 through 618), Taiwan is more often called Lucyu (after the name of a small kingdom in the southwestern part of the island).

The island has been found under its modern name in written sources since 1599. Trade and navigation across the Taiwan Strait between mainland China and the island began long before the Chinese explored it.

The first Chinese military expedition to Taiwan was noticed in the year 230.

In 610, the 10,000-strong Chinese army made a new campaign against Taiwan and Penghuledao, after which links between China and these islands became more regular. Taiwan was officially incorporated into China (as part of the Fujian province) during the twelfth century. During the twelfth to fourteenth centuries, the Chinese tried to gain a foothold in Taiwan, partially mixing with the local population.

In 1360, due to the increasing military importance of the island, the Office of Oversight was founded on it, which was the first Chinese local governing body in Taiwan. During this period, the flow of immigration to the island from the provinces of Fujian and Guangdong increased. The process of the development by the Chinese accelerated, and agriculture and crafts developed. The indigenous tribes were then subsequently forced into the mountainous areas, and the Chinese settlers began to develop fertile coastal lands and coastal-water fishing.

Since the 16th century, the island has become attractive to many. First came the Japanese feudal lords and pirates, who made vain attempts to gain a foothold in Jilong, Kaohsiung, Hualien. These were all successfully repelled. In 1550, a Portuguese ship was sailing not far from Taiwan. The enchanted Portuguese seafarers immediately gave the island  a name, Formosa (Beautiful). In 1550, a Portuguese

a name, Formosa (Beautiful). In 1550, a Portuguese

ship was sailing not far from Taiwan. The enchanted Portuguese seafarers immediately gave the island a name – Formosa (Beautiful).

There is an assumption that the first European who saw the island was Dutchman Jan Huygen van Linschoten (1563 – 8 February 1611).

In 1592 being a navigator (and passing by an island with lush greenery and mountain peaks on a Portuguese sailing ship), he marked it in the logbook as "Formosa".

"Taiwan" has been in use since the early 17th century. In the early 17th century, the Dutch brought buffaloes to Taiwan. Thanks to this, the natives began to use draught cattle.

In 1622 the island came under the control of the Dutch from the East India Company. From 1626, Taiwan started to arouse burning interest in Spain, which intended to send its warships to the shores of the "wonderful" island. Moreover, Spain has managed to gain a foothold in northern Taiwan.

In 1626 Spain sent a fleet of warships from Manila to northern Taiwan and established a small colony named "Spanish Formosa". Fort San Salvador was established to counterbalance Dutch rule in southern Taiwan and protect Spain's interests in the shipping route between China's Fujian province and Manila in the Philippines.

However, in 1642, after several years of battles, the fort was handed over to the Dutch.

The unfolding struggle between Spain and Holland for the possession of the island ended in 1642 to satisfy the interests of the latter.

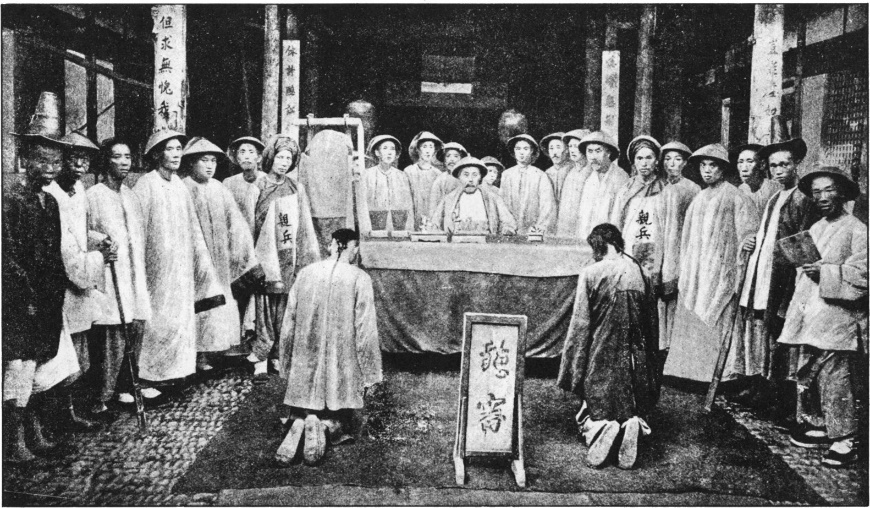

In September 1652, a major uprising of the local aboriginal population under the leadership of Guo Hua broke out against the Dutch colonialists. Inspired rebels tracked scattered groups of Dutchmen appearing in different parts of the island, fighting with them to the death.

There is a mention of a large pit, dug by the rebels in the north of the island and covered up with poles, turves and grass, into which they managed to lure a group of Dutch sailors.

The pit was then re-filled with earth and twigs. Ultimately the forces were unequal, the rebels crushed, and only the northern and southwestern regions of Taiwan remained under the control of the East India Company.

Fort San Salvador has not disappeared without a trace. And we owe this to archaeologists.

In the city of Jilong, a Spanish-Taiwanese expedition found Fort San Salvador, built during the Spanish occupation of Taiwan in 1626-1642. The researchers discovered some Neolithic artefacts, such as bones and shells, plus some items from later periods. A porcelain vial from the Qing Dynasty and which was intended for medicine particularly caught the

attention of the archaeologists. Due to the excavations, the previously planned construction of public parking lots has been discontinued, according to the Mayor of Jilong, Lin Yu-chan

. He noted that these archaeological excavations were very significant. “This is a truly exciting moment in the history of Jilong,” concluded the Mayor.

Arable farming, cattle breeding, crafts, hunting

Horticulture began to develop.

The most widespread crops were cereals (millet, rice), legumes (peas, various beans), and tuberous species (taro, sweet potatoes, yams).

The production of irrigated rice, sugar cane, onions and ginger increased throughout the 17th,18th, & 19th centuries with the crops being harvested twice per year.

The Dutch also introduced the local people to the technology of growing tobacco.

The communal fields were cultivated by women under the guidance of certain men who were known as the “elders of the

field”. In addition to this, every woman and every man worked on their plots.

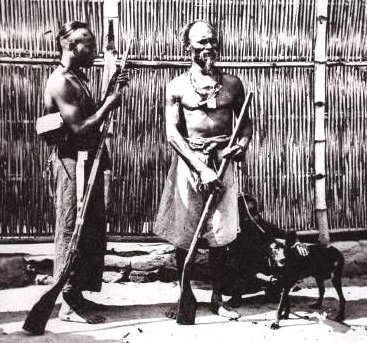

Fishing, crab and oyster catching in the 17th century were exclusively women’s occupations, whereas in the 18 and 19th centuries it became men’s work. For fishing bows and harpoons were used and they set up nets and made dams. But the main occupation for men was hunting. They hunted singly and in groups. Sometimes hunters of 2 or 3 neighbouring communities could unite. They hunted collectively either with stakes and dogs or with the help of snares. The prey was divided-up in the following way: the hunters kept the heads, bones, horns and skins of animals, and the remainder of the meat among all residents. Domestic animals included pigs,  dogs and chickens. Some homeowners had cats. In the 19th century, horses were imported from China but were used only for riding. The food was usually cooked by women. A hearth was made of stones outside the house. Meat was rare on the table. The entrails of animals were salted and salt treatment was also used for unscaled fish. Salt was extracted by evaporating seawater in troughs. They ate with their hands, sometimes helping themselves with coconut shells. Starting from the 18th century, they began to use sticks and porcelain bowls.

dogs and chickens. Some homeowners had cats. In the 19th century, horses were imported from China but were used only for riding. The food was usually cooked by women. A hearth was made of stones outside the house. Meat was rare on the table. The entrails of animals were salted and salt treatment was also used for unscaled fish. Salt was extracted by evaporating seawater in troughs. They ate with their hands, sometimes helping themselves with coconut shells. Starting from the 18th century, they began to use sticks and porcelain bowls.

Grains were ground using a mortar and pestle.

Rice, sweet potatoes and peas were spiced using red pepper. Fruit (bananas, oranges, persimmons) played a secondary role.

Beginning in the 3rd century, they used weapons made of deer antlers, whereas in the 16th century, they began to buy iron arrowheads and knives from the Chinese and daggers from the Japanese.

By the 17th century, they began to smelt iron and make weapons themselves.

Boats were hollowed out of wood. Bamboo was used to make vessels for storing grain and water. Often water was stored in gourds.

The Taiwanese were engaged in spinning, weaving and basket weaving. Bamboo fibres and hemp were used for weaving. Weaving was a man's business. Houses were built from bamboo on a loose foundation. The roof was covered with thatch. They climbed into the house by a ladder. Every five years the houses were demolished and new ones were built. Weapons, objects of labour and household items were all kept in the house. They slept on reindeer skins. Since the 19th century, wealthier people began to use beds. Cowrie shells, necklaces of coral, bamboo, stone, feathers and bone bracelets were all used for decoration. Hair was plucked-out at the temples. The tattoo symbolized affiliation with a particular tribe, clan or age group. Soot and madder plant sap were both used as paint.

Men got married at the age of 21. The groom's relatives engaged in matchmaking. It was necessary to present a gift to the groom's parents or the bride's girlfriends. In some communities, the bride and groom exchanged broken front teeth. Accepting the gift meant agreeing to the marriage. Economic ties were weak, and families easily broke up at the initiative of either side.

Violation of religious prohibitions was considered the most serious of crimes for which there was a fine in the form of rice, meat, skins or wine. Theft, murder, and adultery were considered crimes. In such cases, the custom of revenge was in effect.

The plaintiff and the defendant fought a duel. For his wife’s adultery, the husband took 2 or 3 pigs from the opponent. The Taiwanese worshipped the spirits of the mountains and the sea and sacrificed to them with meat and fish, sprinkling them with water. If a person died in battle the bodily remains were sacrificed to the spirits. The corpse was placed in a small hut, built on the branches of a tree, and shot at with bows or covered with a pile of stones into which a flag was placed.

As we can see, the cult of ancestors, fetishism, and animism was widespread among the tribes. The interpretation of dreams was also popular. The tribal pantheon had paired Deities. We believe that they symbolized both masculine and feminine principles.

The main Deities were Tamagisanchak – the god of rain, and Takarupada – the goddess of thunder, representing beauty and fertility.

Hamo and Pagatao were associated with a solar cult. All tribes believed in good and evil spirits of nature, semi-mythical heroes. The cult of human ancestors and the cult of plant ancestors were widespread. The agricultural cycle was associated with seven holidays accompanied by ritual libations and orgies.

In the 19th century, the funeral rites changed, the body of the deceased being interred without ceremony in an undesignated place. Some tribes preserved legends about the flood, after which the surviving brother and sister became husband and wife and many aborigines descended from them. In folklore, many stories were about shooting at the sun. This plot is reminiscent of the Chinese legend about the archer Yi, the sun and the moon pursuing each other and the immaculate conception, the emergence of agriculture, hunting, fishing, plants and animals.

Conquerors

Dutch Formosa existed until 1661. This year, the Dutch Fort Zeeland (Taiwan), headed by the Swede Frederick Coyett, capitulated to an army of refugees from China, who had

remained loyal to the overthrown Ming dynasty and led by Admiral Koxinga. Today Fort Zeeland is part of the Anlin district of Tainan.

At that time, Taiwan was called Dongning. Under Koxinga and his descendants, the Chinese population of Taiwan (or the so-called then Dongning increased to 200,000 people.

Supporters of Zheng Chenggong created an independent state on the island to fight the Manchus. The latter at this time overthrew the Ming dynasty in China and established their own

Qing dynasty. Subsequently, it took the Manchus 22 years to subdue Taiwan to the Qing dynasty emperors in 1683 following an economic blockade and with the help of

the Dutch. The island, in 1683, was included in the Chinese province of Fujian.

The eastern shores of the island remained uninhabited throughout the 18th century. In the 19th century, Amoy traders sowed the entire territory of Taiwan with rice and tea that they mainly exported to Japan.

The 1842 census showed that Taiwan had 2.5 million inhabitants.

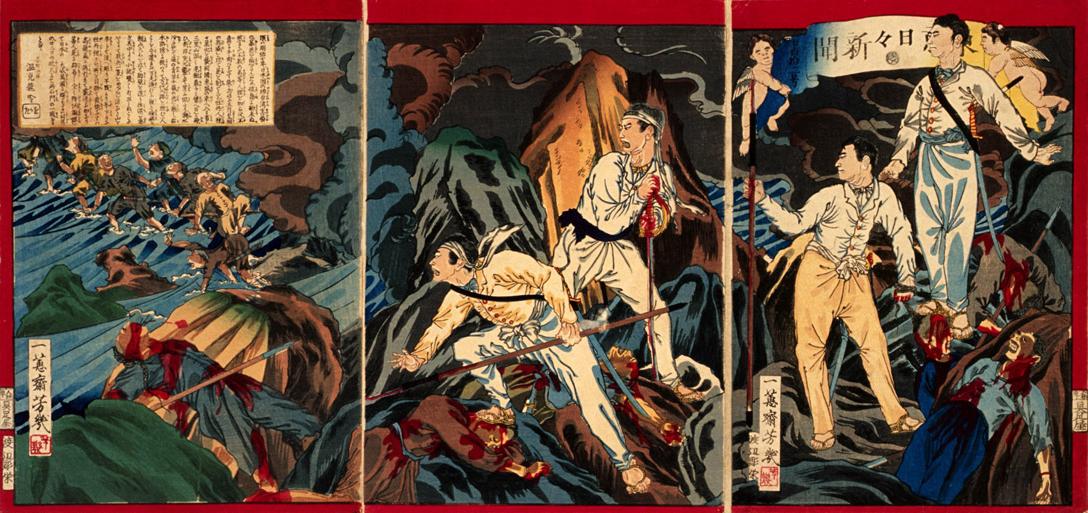

May and June of 1874 marked the so-called Taiwan campaign – the Japanese military operation on the island of Taiwan, which was then under the sovereignty of the Qing dynasty. The campaign was a reaction to the killing of  Japanese nationals (the Ryukyu State trading junk team) by Taiwanese aborigines. Japanese troops managed to capture the southern part of the island and demanded that the Qing dynasty assume responsibility for the killings.

Japanese nationals (the Ryukyu State trading junk team) by Taiwanese aborigines. Japanese troops managed to capture the southern part of the island and demanded that the Qing dynasty assume responsibility for the killings.

Great Britain held the role of intermediary, and Japan withdrew its troops in exchange for the payment of reparations by the Chinese.

Shipwrecks were not uncommon off the southern coast of Taiwan and led to the growth of sea robberies, acts of piracy restricted to attacks on ships washed ashore or stopped in calm waters near the coastline.

In Taiwan, which by 1871 was under the sovereignty of the Chinese Qing dynasty, a diplomatic incident took place. Residents of Taiwanese tribes of the Mudan village killed 54 Japanese fishermen from the Miyakojima island of the Ryukyu  archipelago.

archipelago.

In Taiwan, which by 1871 was under the sovereignty of the Chinese Qing dynasty, a diplomatic incident took place. Residents of Taiwanese tribes of the Mudan village killed 54 Japanese fishermen from the Miyakojima island of the Ryukyu archipelago.

The fishermen were accidentally washed ashore by a wave to the southeastern coast of Taiwan.

The main instigators of the massacre were natives from the Kuarut and Bo-otang tribes.

The 12 surviving crew members were rescued by the Chinese and taken to Taiwan, from where they were handed over to Fujian officials. Later, by agreement, they were sent home.

Ryukyu Archipelago Governor Oyama Tsunayoshi, deputy head of Kagoshima Province, reported to the Japanese central government, calling for revenge. Prudently perhaps, any decision on the issue was postponed.

In 1873, a second similar incident occurred when Taiwanese natives attacked a Japanese ship from the village of Kashiwa, Okayama Prefecture. The ship was wrecked in Taiwanese waters and four crew members were beaten to death.

This event infuriated the Japanese public, which actively demanded the most decisive measures from the authorities. Foreign Minister Soejima Taeomi, sent to the court of Emperor Qing, received an audience with Emperor Tongzhi and appealed to the Chinese side with a demand to compensate for the losses.

Responding, the Qing Dynasty Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that although Taiwan belongs to China, the Taiwanese aborigines are southern barbarians who do not recognize the Qing emperor's supreme power.

Therefore, the latter is not responsible for their actions.

We should note, that until 1895, that is before the transfer of the island to Japan under the Shimonoseki Treaty, the island was divided into two zones:

– the western plains, where the main population was made up of migrants from mainland China; here also lived the indigenous agricultural population – “plain settlers” (pinbu);

– the eastern mountainous zone, where since the 17th century there were restrictions on Chinese migration (the so-called fenshanming – a decree on the closure of the mountains). There was no Chinese administration there, and the local population (Shenfan or Gaoshan – "highlanders") was ruled by elders.

Meanwhile, in Japan, public discontent was growing fuelled by political crisis, unpopular reforms and the outbreak of the Saga uprising.

Encouraged by the Americans, the Japanese government decided to use the recent incidents as an excuse to relieve social tension within the country and carry out a punitive expedition.

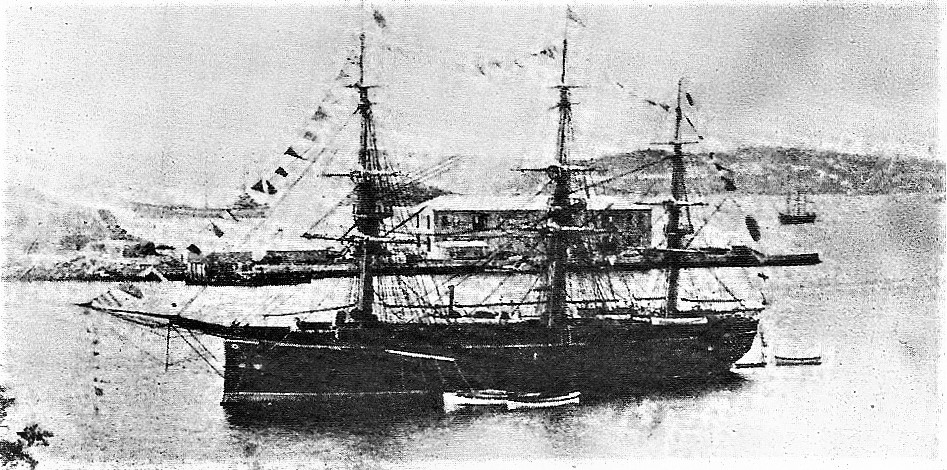

In April 1874, the Imperial Adviser Okumu Shigenobu, was appointed head of the Taiwan appanage office, and Lieutenant General Tsugumichi Saigo was appointed the commander of the troops of this office. In addition to the ground forces, impressive naval forces were also involved, including the armoured corvette Ryujo, built in England not long before these events. But at the last moment, the government halted preparations due to protests from the British and US ambassadors, who said the invasion of Taiwan "would destabilize peace in the Far East."

Despite international pressure, in mid-May 1874, the 3,000-strong contingent of the Imperial Japanese Army under the command of Tsugumichi Saigo unauthorizedly set off to Taiwan. A little later, the Japanese authorities were forced to recognize the legitimacy of the campaign. On 22 May 1874, the Japanese gathered their troops in the Taiwanese port of Sheliao and began punitive action against the Paivan aborigines.

The natives reacted to the Japanese in a quite unfriendly manner, and they gave rise to the opening of hostilities by killing several Japanese soldiers, who carelessly went for a walk away from the camp. The next day, General Saigo sent a detachment of troops into the mountains, which, having destroyed the village and massacred most of the male population of the village, returned to the camp with very few casualties. After that, many tribes laid down their arms and voluntarily surrendered to the Japanese. Just a few mountain villages remained hostile.

The desire to weaken the enemy with a decisive blow prompted Saigo to direct his power against them, as the most powerful and stubborn of all his opponents. On June 13, the Japanese army, divided into three groups, entered the hostile territory from different directions. The Japanese moved without encountering strong resistance. But their situation was not easy. Natural conditions seriously complicated their path: torrential rain, typical for this time of year, flooding of rivers and their rapid flow, lack of roads and unfamiliar area entailed many hardships and difficulties.

And the health of the members of the expedition was adversely affected by constant dampness, intense heat and exhausting work. Many fell ill with fever.

The highlanders avoided open combat, which was unequal for them, while firing at the Japanese with impunity from behind the inaccessible rocks, and disturbing them with unexpected attacks. The combat losses of the Japanese were rather small – only 12 men. But 561 Japanese soldiers died of malaria. The Qing dynasty demanded the immediate withdrawal of Japanese troops from Taiwan.

Terashima, who succeeded Soejima as foreign minister, fearing diplomatic complications, sent Japanese Ambassador Okubo Toshimichi to Nagasaki to suspend the expedition.

In August 1874, Okubo arrived in China, where he began negotiations with Zongliyamen (Foreign Ministry).

The parties were irreconcilable, and these negotiations came to an impasse. Eventually, a compromise was agreed upon with the mediation of the British ambassador to China, Thomas Wade.

China was preoccupied with preparations for war with Yettishar (a Muslim state in Xinjiang that emerged following the Dungan uprising).

On October 31, Japan and Qing concluded a truce, under which Japan had to withdraw its troops from Taiwan, and the Chinese had to pay compensation to injured Japanese sailors and relatives of the victims. It was the first international treaty to recognize Japan's sovereignty over the Ryukyu archipelago. The inhabitants of Ryukyu were now subjects of Japan.

They had to pay approximately 18.7 tons of silver to Japan as an indemnity plus twice as much again to compensate the families of the dead sailors.

In addition to this, they had to pay 75 tons of silver for expenses incurred by the Japanese government for laying roads and erecting buildings on the island.

From that time, the Qing authorities were responsible for policing all cases of sea robbery both on the island and in Chinese waters.

Japan provided Formosa to the Chinese and had to leave the island by December 20, 1874.

One day after the departure of the Japanese expedition, the camp was reduced to ashes, the Chinese burning everything they had bought, considering it to be humiliating to use.

In 1875, Taipei became the capital of northern Taiwan. In 1886 Taiwan was singled out as a separate province of China. The defeat in the war with the Japanese forced the Qing government to cede Taiwan to Japan in 1895.

Under the terms of the Shimonoseki Peace Treaty, Taiwan came under the control of the Japanese administration. Having settled on the island, the Japanese first began to study the local tribes.

They call these tribes "takasago" (as the Japanese read "gaoshan"). The Japanese conduct scientific research and classifications and took control of the island.

Following the outbreak of World War II, some villages were converted into paramilitary camps by the Japanese.

Thus, they prepared the local population for service in the Japanese army. Two raid companies were formed from the Aborigines under the command of Japanese commanders, who took part in the battles in the Pacific Ocean, New Guinea, and the Philippines.

They also took part in raids on the American airfield at Browen. During this raid, a Taiwanese suicide squad named "Kaoru Group" was supposed to blow up American planes. The task was only partially completed.

Generally, these Takasago units were distinguished by their good training and excellent fighting qualities.

Local patriots tried to organize Taiwan, as an independent state, “the Republic of Taiwan ". However, this attempt failed. The new Qing government was defeated in the war with the Japanese and ceded Taiwan to Japan in 1895.