Henty George Alfred

With Kitchener in the Soudan: A Story of Atbara and Omdurman

"Well, I am glad to have heard this, for you know the sort of men interpreters generally are. From the lad's appearance and manner, there is no shadow of doubt that his mother was a lady. I thought it more than probable that she had married beneath her, and that her husband was of the ordinary interpreter class. Now, from what you have said, I see that it is probable he came of a much better family. Well, you may be sure that I shall do what I can for the lad."

Gregory joined him, as he left the bank.

"I think, Hilliard, we had best go to the tailor, first. His shop is not far from here. As you want to get your things in three days, it is as well to have that matter settled, at once."

The two suits, each consisting of khaki tunic, breeches, and putties, were ordered.

"You had better have breeches," he said. "It is likely you will have to ride, and knickerbockers look baggy."

This done, they went to Shepherd's Hotel.

"Sit down in the verandah," Captain Ewart said, "until I get rid of my regimentals. Even a khaki tunic is not an admirable garment, when one wants to be cool and comfortable."

In a few minutes he came down again, in a light tweed suit; and, seating himself in another lounging chair, two cooling drinks were brought in; then he said:

"Now we will talk about your outfit, and what you had best take up. Of course, you have got light underclothing, so you need not bother about that. You want ankle boots–and high ones–to keep out the sand. You had better take a couple of pairs of slippers, they are of immense comfort at the end of the day; also a light cap, to slip on when you are going from one tent to another, after dark. A helmet is a good thing in many ways, but it is cumbrous; and if there are four or five men in a tent, and they all take off their helmets, it is difficult to know where to stow them away.

"Most likely you will get a tent at Dongola, but you can't always reckon upon that, and you may find it very useful to have a light tente d'abri made. It should have a fly, which is useful in two ways. In the first place, it adds to the height and so enlarges the space inside; and in the next place, you can tie it up in the daytime, and allow whatever air there is to pass through. Then, with a blanket thrown over the top, you will find it cooler than a regimental tent.

"Of course, you will want a sword and a revolver, with a case and belt. Get the regulation size, and a hundred rounds of cartridges; you are not likely ever to use a quarter of that number, but they will come in for practice.

"Now, as to food. Of course you get beef, biscuit, or bread, and there is a certain amount of tea, but nothing like enough for a thirsty climate, especially when–which is sometimes the case–the water is so bad that it is not safe to drink, unless it has been boiled; so you had better take up four or five pounds of tea."

"I don't take sugar, sir."

"All the better. There is no better drink than tea, poured out and left to cool, and drunk without sugar. You might take a dozen tins of preserved milk, as many of condensed cocoa and milk, and a couple of dozen pots of jam. Of course, you could not take all these things on if you were likely to move, but you may be at Dongola some time, before there is another advance, and you may as well make yourself as comfortable as you can; and if, as is probable, you cannot take the pots up with you, you can hand them over to those who are left behind. You will have no trouble in getting a fair-sized case taken up, as there will be water carriage nearly all the way.

"A good many fellows have aerated waters sent up, but hot soda water is by no means a desirable drink–not to be compared with tea kept in porous jars; so I should not advise you to bother about it. You will want a water bottle. Get the largest you can find. It is astonishing how much water a fellow can get down, in a long day's march.

"Oh! As to your boots, get the uppers as light as you can–the lighter the better; but you must have strong soles–there are rocks in some places, and they cut the soles to pieces, in no time. The sand is bad enough. Your foot sinks in it, and it seems to have a sort of sucking action, and very often takes the sole right off in a very short time.

"I suppose you smoke?"

"Cigarettes, sir."

"I should advise you to get a pipe, in addition, or rather two or three of them. If they get broken, or lost in the sand, there is no replacing them; and if you don't take to them, yourself, you will find them the most welcome present you can give, to a man who has lost his.

"I should advise you to get a lens. You don't want a valuable one, but the larger the better, and the cheapest that you can buy; it will be quite as good as the best, to use as a burning glass. Matches are precious things out there and, with a burning glass, you will only have to draw upon your stock in the evening.

"Now, do you ride? Because all the white officers with the Egyptian troops do so."

"I am sorry to say that I don't, sir. I have ridden donkeys, but anyone can sit upon a donkey."

"Yes; that won't help you much. Then I should advise you to use all the time that you can spare, after ordering your outfit, in riding. No doubt you could hire a horse."

"Yes; there is no difficulty about that."

"Well, if you will hire one, and come round here at six o'clock tomorrow morning, I will ride out for a couple of hours with you, and give you your first lesson. I can borrow a horse from one of the staff. If you once get to sit your horse, in a workman-like fashion, and to carry yourself well, you will soon pick up the rest; and if you go out, morning and evening, for three hours each time, you won't be quite abroad, when you start to keep up with a column of men on foot.

"As to a horse, it would be hardly worth your while to bother about taking one with you. You will be able to pick one up at Dongola. I hear that fugitives are constantly coming in there, and some of them are sure to be mounted. However, you had better take up a saddle and bridle with you. You might as well get an Egyptian one; in the first place because it is a good deal cheaper, and in the second because our English saddles are made for bigger horses. You need not mind much about the appearance of your animal. Anything will do for riding about at Dongola, and learning to keep your seat. In the first fight you have with Dervish horsemen, there are sure to be some riderless horses, and you may then get a good one, for a pound or two, from some Tommy who has captured one."

"I am sure I am immensely obliged to you, Captain Ewart. That will indeed be an advantage to me."

On leaving the hotel Gregory at once made all his purchases, so as to get them off his mind; and then arranged for the horse in the morning. Then he went home, and told the old servant the change that had taken place in his position.

"And now, what about yourself, what would you like to do?"

"I am too old to go up with you, and cook for you."

"Yes, indeed," he laughed; "we shall be doing long marches. But it is not your age, so much. As an officer, it would be impossible for me to have a female servant. Besides, you want quiet and rest. I have been round to the landlord, to tell him that I am going away, and to pay him a month's rent, instead of notice. I should think the best way would be for you to take a large room for yourself, or two rooms not so large–one of them for you to live in, and the other to store everything there is here. I know that you will look after them, and keep them well. Of course, you will pick out all the things that you can use in your room. It will be very lonely for you, living all by yourself, but you know numbers of people here; and you might engage a girl to stay with you, for some small wages and her food. Now, you must think over what your food and hers will cost, and the rent. Of course, I want you to live comfortably; you have always been a friend rather than a servant, and my mother had the greatest trust in you."

"You are very good, Master Gregory. While you have been away, today, I have been thinking over what I should do, when you went away. I have a friend who comes in, once a week, with fruit and vegetables. Last year, you know, I went out with her and stayed a day. She has two boys who work in the garden, and a girl. She came in today, and I said to her:

"'My young master is going away to the Soudan. What do you say to my coming and living with you, when he has gone? I can cook, and do all about the house, and help a little in the garden; and I have saved enough money to pay for my share of food.'

"She said, 'I should like that, very well. You could help the boys, in the field.'

"So we agreed that, if you were willing, I should go. I thought of the furniture; but if you do not come back here to live, it would be no use to keep the chairs, and tables, and beds, and things. We can put all Missy's things, and everything you like to keep, into a great box, and I could take them with me; or you could have them placed with some honest man, who would only charge very little, for storage."

"Well, I do think that would be a good plan, if you like these people. It would be far better than living by yourself. However, of course I shall pay for your board, and I shall leave money with you; so that, if you are not comfortable there, you can do as I said, take a room here.

"I think you are right about the furniture. How would you sell it?"

"There are plenty of Greek shops. They would buy it all. They would not give as much as you gave for it. Most of them are great rascals."

"We cannot help that," he said. "I should have to sell them when I come back and, at any rate, we save the rent for housing them. They are not worth much. You may take anything you like, a comfortable chair and a bed, some cooking things, and so on, and sell the rest for anything you can get, after I have gone. I will pack my dear mother's things, this evening."

For the next two days, Gregory almost lived on horseback; arranging, with the man from whom he hired the animals, that he should change them three times a day. He laid aside his black clothes, and took to a white flannel suit, with a black ribbon round his straw hat; as deep mourning would be terribly hot, and altogether unsuited for riding.

"You will do, lad," Captain Ewart said to him, after giving him his first lesson. "Your fencing has done much for you, and has given you an easy poise of body and head. Always remember that it is upon balancing the body that you should depend for your seat; although, of course, the grip of the knees does a good deal. Also remember, always, to keep your feet straight; nothing is so awkward as turned-out toes. Besides, in that position, if the horse starts you are very likely to dig your spurs into him.

"Hold the reins firmly, but don't pull at his head. Give him enough scope to toss his head if he wants to, but be in readiness to tighten the reins in an instant, if necessary."

Each day, Gregory returned home so stiff, and tired, that he could scarcely crawl along. Still, he felt that he had made a good deal of progress; and that, when he got up to Dongola, he would be able to mount and ride out without exciting derision. On the morning of the day on which he was to start, he went to say goodbye to Mr. Murray.

"Have you everything ready, Hilliard?" the banker asked.

"Yes, sir. The uniform and the tent are both ready. I have a cork bed, and waterproof sheet to lay under it; and, I think, everything that I can possibly require. I am to meet Captain Ewart at the railway, this afternoon at five o'clock. The train starts at half past.

"I will draw another twenty-five pounds, sir. I have not spent more than half what I had, but I must leave some money with our old servant. I shall have to buy a horse, too, when I get up to Dongola, and I may have other expenses, that I cannot foresee."

"I think that is a wise plan," the banker said. "It is always well to have money with you, for no one can say what may happen. Your horse may get shot or founder, and you may have to buy another. Well, I wish you every luck, lad, and a safe return."

"Thank you very much, Mr. Murray! All this good fortune has come to me, entirely through your kindness. I cannot say how grateful I feel to you."

Chapter 5: Southward

At the hour named, Gregory met Captain Ewart at the station. He was now dressed in uniform, and carried a revolver in his waist belt, and a sword in its case. His luggage was not extensive. He had one large bundle; it contained a roll-up cork bed, in a waterproof casing. At one end was a loose bag; which contained a spare suit of clothes, three flannel shirts, and his underclothing. This formed the pillow. A blanket and a waterproof sheet were rolled up with it. In a small sack was the tente d'abri, made of waterproof sheeting, with its two little poles. It only weighed some fifteen pounds. His only other luggage consisted of a large case, with six bottles of brandy, and the provisions he had been recommended to take.

"Is that all your kit?" Captain Ewart said, as he joined him.

"Yes, sir. I hope you don't think it is too much."

"No; I think it is very moderate, though if you move forward, you will not be able to take the case with you, The others are light enough, and you can always get a native boy to carry them. Of course, you have your pass?"

"Yes, sir. I received it yesterday, when I went to headquarters for the letter to General Hunter."

"Then we may as well take our places, at once. We have nearly an hour before the train starts; but it is worth waiting, in order to get two seats next the window, on the river side. We need not sit there till the train starts, if we put our traps in to keep our places. I know four or five other officers coming up, so we will spread our things about, and keep the whole carriage to ourselves, if we can."

In an hour, the train started. Every place was occupied. Ewart had spoken to his friends, as they arrived, and they had all taken places in the same compartment. The journey lasted forty hours, and Gregory admitted that the description Captain Ewart had given him, of the dust, was by no means exaggerated. He had brought, as had been suggested, a water skin and a porous earthenware bottle; together with a roll of cotton-wool to serve as a stopper to the latter, to keep out the dust. In a tightly fitting handbag he had an ample supply of food for three days. Along the opening of this he had pasted a strip of paper.

"That will do very well for your first meal, Hilliard, but it will be of no good afterwards."

"I have prepared for that," Gregory said. "I have bought a gum bottle, and as I have a newspaper in my pocket, I can seal it up after each meal."

"By Jove, that is a good idea, one I never thought of!"

"The gum will be quite sufficient for us all, up to Assouan. I have two more bottles in my box. That should be sufficient to last me for a long time, when I am in the desert; and as it won't take half a minute to put a fresh paper on, after each meal, I shall have the satisfaction of eating my food without its being mixed with the dust."

There was a general chorus of approval, and all declared that they would search every shop in Assouan, and endeavour to find gum.

"Paste will do as well," Ewart said, "and as we can always get flour, we shall be able to defy the dust fiend as far as our food goes.

"I certainly did not expect that old campaigners would learn a lesson from you, Hilliard, as soon as you started."

"It was just an idea that occurred to me," Gregory said.

The gum bottle was handed round, and although nothing could be done for those who had brought their provisions in hampers, three of them who had, like Gregory, put their food in bags, were able to seal them up tightly.

It was now May, and the heat was becoming intolerable, especially as the windows were closed to keep out the dust. In spite of this, however, it found its way in. It settled everywhere. Clothes and hair became white with it. It worked its way down the neck, where the perspiration changed it into mud. It covered the face, as if with a cake of flour.

At first Gregory attempted to brush it off his clothes, as it settled upon them, but he soon found that there was no advantage in this. So he sat quietly in his corner and, like the rest, looked like a dirty white statue. There were occasional stops, when they all got out, shook themselves, and took a few mouthfuls of fresh air.

Gregory's plan, for keeping out the dust from the food, turned out a great success; and the meals were eaten in the open air, during the stoppages.

On arriving at Assouan, they all went to the transport department, to get their passes for the journey up the Nile, as far as Wady Halfa. The next step was to go down to the river for a swim and, by dint of shaking and beating, to get rid of the accumulated dust.

Assouan was not a pleasant place to linger in and, as soon as they had completed their purchases, Captain Ewart and Gregory climbed on to the loaded railway train, and were carried by the short line to the spot where, above the cataract, the steamer that was to carry them was lying. She was to tow up a large barge, and two native craft. They took their places in the steamer, with a number of other officers–some newcomers from England, others men who had been down to Cairo, to recruit. They belonged to all branches of the service, and included half a dozen of the medical staff, three of the transport corps, gunners, engineers, cavalry, and infantry. The barges were deep in the water, with their cargoes of stores of all kinds, and rails and sleepers for the railway, and the steamer was also deeply loaded.

The passage was a delightful one, to Gregory. Everything was new to him. The cheery talk and jokes of the officers, the graver discussion of the work before them, the calculations as to time and distance, the stories told of what had taken place during the previous campaign, by those who shared in it, were all so different from anything he had ever before experienced, that the hours passed almost unnoticed. It was glorious to think that, in whatever humble capacity, he was yet one of the band who were on their way up to meet the hordes of the Khalifa, to rescue the Soudan from the tyranny under which it had groaned, to avenge Gordon and Hicks and the gallant men who had died with them!

Occasionally, Captain Ewart came up and talked to him, but he was well content to sit on one of the bales, and listen to the conversation without joining in it. In another couple of years he, too, would have had his experiences, and would be able to take his part. At present, he preferred to be a listener.

The distance to Wady Halfa was some three hundred miles; but the current was strong, and the steamer could not tow the boats more than five miles an hour, against it. It was sixty hours, from the start, before they arrived.

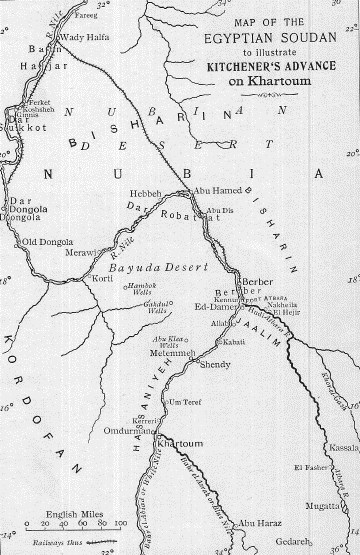

Gregory was astonished at the stir and life in the place. Great numbers of native labourers were at work, unloading barges and native craft; and a line of railway ran down to the wharves, where the work of loading the trucks went on briskly. Smoke pouring out from many chimneys, and the clang of hammers, told that the railway engineering work was in full swing. Vast piles of boxes, cases, and bales were accumulated on the wharf, and showed that there would be no loss of time in pushing forward supplies to Abu Hamed, as soon as the railway was completed to that point.

Wady Halfa had been the starting point of a railway, commenced years before. A few miles have been constructed, and several buildings erected for the functionaries, military and civil; but Gordon, when Governor of the Soudan, had refused to allow the province to be saddled with the expenses of the construction, or to undertake the responsibility of carrying it out.

In 1884 there was some renewal of work and, had Gordon been rescued, and Khartoum permanently occupied, the line would no doubt have been carried on; but with the retirement of the British troops, work ceased, and the great stores of material that had been gathered there remained, for years, half covered with the sand. In any other climate this would have been destructive, but in the dry air of Upper Egypt they remained almost uninjured, and proved very useful, when the work was again taken up.

It was a wonderful undertaking, for along the two hundred and thirty-four miles of desert, food, water, and every necessary had to be carried, together with all materials for its construction. Not only had an army of workmen to be fed, but a body of troops to guard them; for Abu Hamed, at the other end of the line, for which they were making, was occupied by a large body of Dervishes; who might, at any moment, swoop down across the plain.

Had the Sirdar had the resources of England at his back, the work would have been easier, for he could have ordered from home new engines, and plant of every description; but it was an Egyptian work, and had to be done in the cheapest possible way. Old engines had to be patched up, and makeshifts of all kinds employed. Fortunately he had, in the chief engineer of the line, a man whose energy, determination, and resource were equal to his own. Major Girouard was a young officer of the Royal Engineers and, like all white officers in the Egyptian service, held the rank of major. He was a Canadian by birth, and proved, in every respect, equal to the onerous and responsible work to which he was appointed.

However, labour was cheap, and railway battalions were raised among the Egyptian peasants, their pay being the same as that of the soldiers. Strong, hearty, and accustomed to labour and a scanty diet, no men could have been more fitted for the work. They preferred it to soldiering; for although, as they had already shown, and were still further to prove, the Egyptian can fight, and fight bravely; he is, by nature, peaceable, and prefers work, however hard. In addition to these battalions, natives of the country and of the Soudan, fugitives from ruined villages and desolated plains, were largely employed.

The line had now been carried three-quarters of the distance to Abu Hamed, which was still in the hands of the Dervishes. It had been constructed with extraordinary rapidity, for the ground was so level that only occasional cuttings were needed. The organization of labour was perfect. The men were divided into gangs, each under a head man, and each having its own special work to do. There were the men who unloaded the trucks, the labourers who did the earth work, and the more skilled hands who levelled it. As fast as the trucks were emptied, gangs of men carried the sleepers forward, and laid them down roughly in position; others followed, and corrected the distance between each. The rails were then brought along and laid down, with the fish plates, in the proper places; men put these on, and boys screwed up the nuts. Then plate layers followed and lined the rails accurately; and, when this was done, sand was thrown in and packed down between the sleepers.

By this division of labour, the line was pushed on from one to two miles a day, the camp moving forward with the line. Six tank trucks brought up the water for the use of the labourers, daily, and everything worked with as much regularity as in a great factory at home. Troops of friendly tribesmen, in our pay, scoured the country and watched the wells along the road, farther to the east, so as to prevent any bands of Dervishes from dashing suddenly down upon the workers.

At Wady Halfa, Captain Ewart and two or three other officers left the steamer, to proceed up the line. Gregory was very sorry to lose him.

"I cannot tell you, Captain Ewart," he said, "how deeply grateful I feel to you, for the immense kindness you have shown me. I don't know what I should have done, had I been left without your advice and assistance in getting my outfit, and making my arrangements to come up here."

"My dear lad," the latter said, "don't say anything more. In any case, I should naturally be glad to do what I could, for the son of a man who died fighting in the same cause as we are now engaged in. But in your case it has been a pleasure, for I am sure you will do credit to yourself, and to the mother who has taken such pains in preparing you for the work you are going to do, and in fitting you for the position that you now occupy."

As the officers who had come up with them in the train from Cairo were all going on, and had been told by Ewart something of Gregory's story, they had aided that officer in making Gregory feel at home in his new circumstances; and in the two days they had been on board the boat, he had made the acquaintance of several others.

The river railway had now been carried from Wady Halfa to Kerma, above the third cataract. The heavy stores were towed up by steamers and native craft. Most of the engines and trucks had been transferred to the desert line; but a few were still retained, to carry up troops if necessary, and aid the craft in accumulating stores.

One of these trains started a few hours after the arrival of the steamer at Wady Halfa. Gregory, with the officers going up, occupied two horse boxes. Several of them had been engaged in the last campaign, and pointed out the places of interest.

At Sarras, some thirty miles up the road, there had been a fight on the 29th of April, 1887; when the Dervish host, advancing strong in the belief that they could carry all before them down to the sea, were defeated by the Egyptian force under the Sirdar and General Chermside.

The next stop of the train was at Akasheh. This had been a very important station, before the last advance, as all the stores had been accumulated here when the army advanced. Here had been a strongly entrenched camp, for the Dervishes were in force, fifteen miles away, at Ferket.

"It was a busy time we had here," said one of the officers, who had taken a part in the expedition. "A fortnight before, we had no idea that an early move was contemplated; and indeed, it was only on the 14th of March that the excitement began. That day, Kitchener received a telegram ordering an immediate advance on Dongola. We had expected it would take place soon; but there is no doubt that the sudden order was the result of an arrangement, on the part of our government with Italy, that we should relieve her from the pressure of the Dervishes round Kassala by effecting a diversion, and obliging the enemy to send a large force down to Dongola to resist our advance.

"It was a busy time. The Sirdar came up to Wady Halfa, and the Egyptian troops were divided between that place, Sarras, and Akasheh. The 9th Soudanese were marched up from Suakim, and they did the distance to the Nile (one hundred and twenty miles) in four days. That was something like marching.

"Well, you saw Wady Halfa. For a month, this place was quite as busy. Now, its glories are gone. Two or three huts for the railway men, and the shelters for a company of Egyptians, represent the whole camp."

As they neared Ferket the officer said:

"There was a sharp fight out there on the desert. A large body of Dervishes advanced, from Ferket. They were seen to leave by a cavalry patrol. As soon as the patrol reached camp, all the available horse, two hundred and forty in number, started under Major Murdoch. Four miles out, they came in sight of three hundred mounted Dervishes, with a thousand spearmen on foot.

"The ground was rough, and unfavourable for a cavalry charge; so the cavalry retired to a valley, between two hills, in order to get better ground. While they were doing so, however, the Dervishes charged down upon them. Murdoch rode at them at once, and there was a hand-to-hand fight that lasted for twenty minutes. Then the enemy turned, and galloped off to the shelter of the spearmen. The troopers dismounted and opened fire; and, on a regiment of Soudanese coming up, the enemy drew off.

"Eighteen of the Dervishes were killed, and eighty wounded. Our loss was very slight; but the fight was a most satisfactory one, for it showed that the Egyptian cavalry had, now, sufficient confidence in themselves to face the Baggara.

"Headquarters came up to Akasheh on the 1st of June. The spies had kept the Intelligence Department well informed as to the state of things at Ferket. It was known that three thousand troops were there, led by fifty-seven Emirs. The ground was carefully reconnoitred, and all preparation made for an attack. It was certain that the Dervishes also had spies, among the camel drivers and camp followers, but the Sirdar kept his intentions secret, and on the evening of June 5th it was not known to any, save three or four of the principal officers, that he intended to attack on the following morning. It was because he was anxious to effect a complete surprise that he did not even bring up the North Staffordshires.

"There were two roads to Ferket–one by the river, the other through the desert. The river column was the strongest, and consisted of an infantry division, with two field batteries and two Maxims. The total strength of the desert column, consisting of the cavalry brigade, camel corps, a regiment of infantry, a battery of horse artillery, and two Maxims–in all, two thousand one hundred men–were to make a detour, and come down upon the Nile to the south of Ferket, thereby cutting off the retreat of the enemy.

"Carrying two days' rations, the troops started late in the afternoon of the 6th, and halted at nine in the evening, three miles from Ferket. At half-past two they moved forward again, marching quietly and silently; and, at half-past four, deployed into line close to the enemy's position. A few minutes later the alarm was given; and the Dervishes, leaping to arms, discovered this formidable force in front of them; and at the same time found that their retreat was cut off, by another large body of troops in their rear; while, on the opposite bank of the river, was a force of our Arab allies.