Henty George Alfred

Through Three Campaigns: A Story of Chitral, Tirah and Ashanti

Then he examined and tried on the uniform of the dead sepoy; which Robah had, that evening, received from the risaldar. It fitted him fairly well. In addition to the regular uniform there was a posteen, or sheepskin coat; loose boots made of soft skin, so that the feet could be wrapped up in cloth before they were put on; and putties, or leggings, consisting of a very long strip of cloth terminating with a shorter strip of leather. These things had been served out that day to the troops, and were to be put on over the usual leg wrappings when they came to snow-covered country. They were to be carried with the men's kits till required. For ordinary wear there were the regular boots, which were strapped on like sandals.

"Well, I think I ought to be able to stand anything in the way of cold, with this sheepskin coat and the leggings, together with my own warm underclothing."

"You are sure," Robah said, "that you understand the proper folding of your turban?"

"I think so, Robah. I have seen them done up hundreds of times but, nevertheless, you shall give me a lesson when you join me tomorrow. We shall have plenty of time for it.

"Now, can you think of anything else that would be useful? If so, you can buy it tomorrow before you come out to meet me."

"No, sahib. There are the warm mittens that have been served out for mountain work; and you might take a pair of your own gloves to wear under them for, from all I hear, you will want them when you are standing out all night on picket work, among the hills."

"No, I won't take the gloves, Robah. With two pairs on, my fingers would be so muffled that I should not be able to do good shooting."

"Well, it will be cold work, for it is very late in the season and, you know, goggles have been served out to all the men to save them from snow blindness, from which they would otherwise suffer severely. I have been on expeditions in which a third of the men were quite blind, when they returned to camp."

"It must look very rum to see a whole regiment marching in goggles," Lisle laughed; "still, anything is better than being blinded."

"I shall see you sometimes, sahib; for the major engaged me, this morning, to go with him as his personal servant, as his own man is in feeble health and, though I am now getting on in years, I am still strong enough to travel with the regiment."

"I am delighted, indeed, to hear that, Robah. I shall be very glad to steal away sometimes, and have a chat with you. It will be a great pleasure to have someone I can talk to, who knows me. Of course, the native officer in command of my company will not be able to show me any favour, nor should I wish him to do so. It seems like keeping one friend, while I am cut off from all others; though I dare say I shall make some new ones among the sepoys. I have no doubt you will be very comfortable with the major."

"Yes, sahib, I am sure that he is a kind master. I shall be able, I hope, sometimes to give you a small quantity of whisky, to mix with the water in your bottle."

"No, no, Robah, when the baggage is cut down there will be very little of that taken and, however much there might be, I could not accept any that you had taken from the major's store. I must fare just the same as the others."

"Well, sahib, I hope that, at any rate, you will carry a small flask of it under your uniform. You may not want it but, if you were wounded and lying in the snow, it would be very valuable to you for, mixed with the water in your bottle, and taken from time to time, it would sustain you until you could be carried down to camp."

"That is a very good idea, Robah, and I will certainly adopt it. I will carry half a pint about with me, for emergencies such as you describe. If I do not want it, myself, it may turn out useful to keep up some wounded comrade. It will not add much to the load that I shall have to carry, and which I expect I shall feel, when we first march. As I am now, I think I could keep up with the best marcher in the regiment but, with the weight of the clothes and pouches, a hundred and twenty rounds of ammunition, and my rifle, it will be a very different thing; and I shall be desperately tired, by the time we get to the end of the day's march.

"Now it is twelve o'clock, and time to turn in, for we march at five."

The next morning, when the sick convoy started, the white officers came up to say goodbye to Lisle; and all expressed their regret that he could not accompany the regiment. The butler had gone on ahead and, as soon as Lisle slipped away, he came up to him and assisted him to make his toilet. He stained him from head to foot, dyed his hair, and fastened in it some long bunches of black horse hair, which he would wear in the Punjabi fashion on the top of his head. With the same dye he darkened his eyelashes and, when he had put on his uniform, he said:

"As far as looks go, sahib, it is certain that no one would suspect that you were not a native. There is a large bottle of stain. You will only have to do yourself over, afresh, about once in ten days. A little of this mixed with three times the amount of water will be sufficient for, if you were to put it on by itself, it would make you a great deal too dark."

They spent the day in a grove and, when evening approached, returned to camp.

"And now, goodbye, sahib! The regiment will march tomorrow morning, at daybreak. I may not have an opportunity of seeing you again, before we start. I hope I have done right, in aiding you in your desire to accompany the expedition; but I have done it for the best, and you must not blame me if harm comes of it."

"That you may be sure I will not, and I am greatly obliged to you. Now, for the present, goodbye!"

Chapter 2: The Start

The havildar was on the lookout for Lisle when he entered the camp; but he did not know him, in his changed attire and stained face, until the lad spoke to him.

"You are well disguised, indeed, sahib," he said. "I had no idea that it was you. Now, my instructions are to take you to Gholam Singh's tent."

Here Lisle found the risaldar and the other two native officers. He saluted as he entered. The risaldar examined him carefully, before speaking.

"Good!" he said; "I did not think that a white sahib could ever disguise himself to pass as a native, though I know that it has been done before now. Certainly I have no fear of any of the white officers finding that you are not what you seem to be. I am more afraid, however, of the men. Still, even if they guessed who you are, they would not, I am sure, betray you.

"Here are your rifle and bayonet. These complete your outfit. I see that you have brought your kit with you. It is rather more bulky than usual, but will pass with the rest.

"The subadar will take you down to the men's lines. I have arranged that you shall be on the baggage guard, at first, so that you will gradually begin to know a few men of your company. They will report to the rest the story you tell them, and you will soon be received as one of themselves.

"I will see that that sack of yours goes with the rest of the kits in the baggage waggon. These officers of your company all understand that you are to be treated like the rest of the men, and not to be shown any favour. At the same time, when in camp, if there is anything that you desire, or any complaint you have to make, you can talk quietly to one of them; and he will report it to me, in which case you may be sure that I shall set the matter right, if possible."

"I don't think there is any fear of that, risaldar. I am pretty well able to take care of myself. My father gave me many lessons in boxing; and I fancy that, although most of the men are a great deal bigger and stronger than I am, I shall be able to hold my own."

"I hope so, Bullen," the havildar said gravely, "but I trust that there will be no occasion to show your skill. We Punjabis are a quiet race of men; and though, of course, quarrels occasionally occur among us, they generally end in abuse, and very seldom come to blows. The greater portion of the regiment has been with us for some years. They know each other well, and are not given to quarrelling. They will scarcely even permit their juniors to go to extremes, and I need not say that the officers of the company would interfere, at once, if they saw any signs of a disturbance.

"I have had a meal cooked, which I hope you will eat with us. It is the last you are likely to be able to enjoy, for some time. We shall feel honoured if you will sit down with us."

An excellent repast was served, and Lisle did it full justice. Then the officers all shook him by the hand, and he started with the subadar for the men's lines, with hearty thanks to the others. When they arrived at the huts, the subadar led the way in.

"Here is a new comrade," he said, as some of the men roused themselves from the ground on his entrance. "He is a cousin of Mutteh Ghar, and bears the same name. It seems that he has served in another regiment, for a short time; but was discharged, owing to sickness. He has now perfectly recovered health, and has come to join his cousin; who, on his arrival, he finds to be dead. He is very anxious to accompany the regiment and, as he understands his work, the risaldar has consented to let him go, instead of remaining behind at the depot.

"He is, of course, much affected by the loss of his cousin; and hopes that he will not be worried by questions. He will be on baggage guard tomorrow, and so will be left alone, until he recovers somewhat from his disappointment and grief."

"I will see to it, subadar," one of the sergeants said. "Mutteh Ghar was a nice young fellow, and we shall all welcome his cousin among us, if he is at all like him."

"Thank you, sergeant! I am sure you will all like him, when you come to know him; for he is a well-spoken young fellow, and I hope that he will make as good a soldier. Good night!"

So saying, he turned and left the tent.

Half an hour later, Lisle was on parade. There were but eight British officers; including the colonel, major, and adjutant, and one company officer to each two companies. The inspection was a brief one. The company officer walked along the line, paying but little attention to the men; but carefully scrutinizing their arms, to see that they were in perfect order. The regiment was put through a few simple manoeuvres; and then dismissed, as work in earnest would begin on the following morning.

Four men in each company were then told off to pack the baggage in the carts. Lisle was one of those furnished by his company. There was little talk while they were at work. In two hours the carts were packed. Then, as they returned to the lines, his three comrades entered into conversation with him.

"You are lucky to be taken," one said, "being only a recruit. I suppose it was done so that you might fill the place of your cousin?"

"Yes, that was it. They said that I had a claim; so that, if I chose, I could send money home to his family."

"They are good men, the white officers," another said. "They are like fathers to us, and we will follow them anywhere. We lately lost one of them, and miss him sorely. However, they are all good.

"We are all glad to be going on service. It is dull work in cantonments."

On arriving at the lines of the company, one of them said:

"The risaldar said that you will take your cousin's place. He slept in the same hut as I. You will soon find yourself at home with us."

He introduced Lisle to the other occupants of the hut, eighteen in number. Lisle then proceeded to follow the example of the others, by taking off his uniform and stripping to the loincloth, and a little calico jacket. He felt very strange at first, accustomed though he was to see the soldiers return to their native costume.

"Your rations are there, and those of our new comrade," one of the party said.

Several fires were burning, and Lisle followed the example of his comrade, and took the lota which formed part of his equipment, filled it with water, and put it in the ashes; adding, as soon as it boiled, the handful of rice, some ghee, and a tiny portion of meat. In an hour the meal was cooked and, taking it from the fire, he sat down in a place apart; as is usual among the native troops, who generally have an objection to eat before others.

"Those who have money," his comrade said, "can buy herbs and condiments of the little traders, and greatly improve their mess."

This Lisle knew well.

"I have a few pice," he said, "but must be careful till I get my pay."

As soon as night fell all turned in, as they were to start at daylight.

"Here is room for you at my side, comrade," the sergeant said. "You had better get to sleep, as soon as you can. Of course, you have your blanket with you?"

"Yes, sergeant."

Lisle rolled himself in his blanket and lay down, covering his face, as is the habit of all natives of India. It was some time before he went to sleep. The events of the day had been exciting, and he was overjoyed at finding that his plan had so far succeeded. He was now one of the regiment and, unless something altogether unexpected happened, he was certain to take part in a stirring campaign.

While it was still dark, he was aroused by the sound of a bugle.

"The men told off to the baggage guard will at once proceed to pack the waggons," the sergeant said.

Lisle at once got up and put on his uniform, as did three other men in the tent. The kits and baggage had already been packed, the night before; and the men of the guard, consisting of a half company, proceeded to the waggons. Half an hour afterwards, another bugle roused the remainder of the regiment, and they soon fell in.

It was broad daylight when they started, the baggage followed a little later. The havildar who was in charge of them was, fortunately, one of those of Lisle's company. There was but little talk at the hurried start. Two men accompanied each of the twelve company waggons. Half the remainder marched in front, and the others behind. Lisle had been told off to the first waggon.

It was a long march, two ordinary stages being done in one. As the animals were fresh, the transport arrived at the camping ground within an hour of the main column. Accustomed though he was to exercise, Lisle found the weight of his rifle, pouches, and ammunition tell terribly upon him. He was not used to the boots and, before half the journey was completed, began to limp. The havildar, noticing this, ordered him to take his place on the top of the baggage on his waggon.

"It is natural that you should feel it, at first, Mutteh Ghar," he said. "You will find it easy enough to keep up with them, after a few days' rest."

Lisle was thankful, indeed, for he had begun to feel that he should never be able to hold on to the end of the march. He remained on the baggage for a couple of hours, and then again took his place by the side of the waggon; receiving an approving nod from the havildar, as he did so.

When the halt was called, the men at once crowded round the waggons. The kits were distributed and, in a few minutes, the regiment had the appearance of a concourse of peaceable peasants. No tents had been taken with them. Waterproof sheets had been provided and, with these, little shelters had been erected, each accommodating three men. The sergeant told Lisle off to share one of these shelters with two other men. A party meanwhile had gone to collect firewood and, in half an hour, the men were cooking their rice.

"Well, how did you like the march?" one of them said to Lisle.

"I found it very hard work," Lisle said, "but the havildar let me ride on the top of one of the waggons for a couple of hours and, after that, I was able to march in with the rest."

"It was a rough march for a recruit," the other said, "but you will soon get used to that. Grease your feet well before you put on your bandages. You will find that that will ease them very much, and that you will not get sore feet, as you would if you marched without preparation."

Lisle took the advice, and devoted a portion of his rations for the purpose, the last thing at night; and found that it abated the heat in his feet, and he was able to get about in comfort.

Each soldier carried a little cooking pot. Although the regiment was composed principally of Punjabis, many of the men were of different nationalities and, although the Punjabis are much less particular about caste than the people of Southern India, every man prepared his meal separately. The rations consisted of rice, ghee, a little curry powder, and a portion of mutton. From these Lisle managed to concoct a savoury mess, as he had often watched the men cooking their meals.

The sergeant had evidently chosen two good men to share the tent with Lisle. They were both old soldiers, not given to much talking; and were kind to their young comrade, giving him hints about cooking and making himself comfortable, and abstaining from asking many questions. They were easily satisfied with his answers and, after the meal was eaten, sat down with him and talked of the coming campaign. Neither of them had ever been to Chitral, but they knew by hearsay the nature of the road, and discussed the probability of the point at which serious opposition would begin; both agreeing that the difficulties of crossing the passes, now that these would be covered with snow, would be far greater than any stand the tribesmen might make.

"They are tough fighters, no doubt," one of them said; "and we shall have more difficulty, with them, than we have ever had before; for they say that a great many of them are armed with good rifles, and will therefore be able to annoy us at a distance, when their old matchlocks would have been useless."

"And they are good shots, too."

"There is no doubt about that; quite as good as we are, I should say. There will be a tremendous lot of flanking work to keep them at a distance but, when it comes to anything like regular fighting, we shall sweep them before us.

"From what I hear, however, we shall only have three or four guns with us. That is a pity for, though the tribesmen can stand against a heavy rifle fire, they have a profound respect for guns. I expect, therefore, that we shall have some stiff fighting.

"How do you like the prospect, Mutteh Ghar?"

"I don't suppose I shall mind it when I get accustomed to it," Lisle said. "It was because I heard that the regiment was about to advance that I hurried up to join. I don't think I should have enlisted, had it been going to stay in the cantonment."

"That is the right spirit," the other said approvingly. "It is the same with all of us. There is no difficulty in getting recruits, when there is fighting to be done. It is the dull life in camp that prevents men from joining. We have enlisted twice as many men, in the past three months, as in three years before."

So they talked till night fell and then turned in; putting Lisle between them, that being the warmest position.

In the morning the march was resumed in the same order, Lisle again taking his place with the baggage guard. The march this time was only a single one; but it was long, nevertheless. Lisle was able to keep his place till the end, feeling great benefit from the ghee which he had rubbed on his feet. The havildar, at starting, said a few cheering words to him; and told him that, when he felt tired, he could put his rifle and pouch in the waggon, as there was no possibility of their being wanted.

His two comrades, when they heard that he had accomplished the march without falling out, praised him highly.

"You have showed good courage in holding on," one of them said. "The march was nothing to us seasoned men, but it must have been trying to you, especially as your feet cannot have recovered from yesterday. I see that you will make a good soldier, and one who will not shirk his work. Another week, and you will march as well as the best of us."

"I hope so," Lisle said. "I have always been considered a good walker. As soon as I get accustomed to the weight of the rifle and pouch, I have no doubt that I shall get on well enough."

"I am sure you will," the other said cordially, "and I think we are as good marchers as any in India. We certainly have that reputation and, no doubt, it was for that reason we were chosen for the expedition, although there are several other regiments nearer to the spot.

"From what I hear, Colonel Kelly will be the commanding officer of the column, and we could not wish for a better. I hear that there is another column, and a much stronger one, going from Peshawar. That will put us all on our mettle, and I will warrant that we shall be the first to arrive there; not only because we are good marchers, but because the larger the column, the more trouble it has with its baggage.

"Baggage is the curse of these expeditions. What has to be considered is not how far the troops can go, but how far the baggage animals can keep up with them. Some of the animals are no doubt good, but many of them are altogether unfitted for the work. When these break down they block a whole line; and often, even if the march is a short one, it is very late at night before the last of the baggage comes in; which means that we get neither kit, blankets, nor food, and think ourselves lucky if we get them the next morning.

"The government is, we all think, much to blame in these matters. Instead of procuring strong animals, and paying a fair price for them; they buy animals that are not fit to do one good day's march. Of course, in the end this stinginess costs them more in money, and lives, than if they had provided suitable animals at the outset."

Lisle had had a great deal of practice with the rifle, and had carried away several prizes shot for by the officers; but he was unaccustomed to carry one for so many hours, and he felt grateful, indeed, when a halt was sounded. Fires were lighted, and food cooked; and then all lay down, or sat in groups in the shade of a grove. The sense of the strangeness of his condition had begun to wear off, and he laughed and talked with the others, without restraint.

Up to the time when he joined the regiment, Lisle had heard a good deal of the state of affairs at Chitral; and his impression of the natives was that they were as savage and treacherous a race as was to be found in Afghanistan and Kashmir. Beyond that, he had not interested himself in the matter; but now, from the talk of his companions, he gained a pretty clear idea of the situation.

Old Aman-ul-mulk had died in August, 1892. He had reigned long; and had, by various conquests and judicious marriages, raised Chitral to a position of importance. The Chitralis are an Aryan race, and not Pathans; and have a deep-rooted hatred of the Afghans.

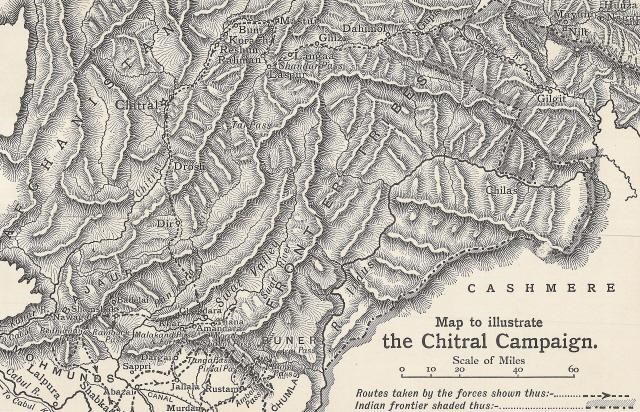

In 1878 Aman placed Chitral under the nominal suzerainty of the Maharajah of Kashmir and, Kashmir being one of the tributary states of the Indian Empire, this brought them into direct communication with the government of India; and Aman received with great cordiality two missions sent to him. When he died, his eldest son Nizam was away from Chitral; and the government was seized by his second son, Afzul; who, however, was murdered by his uncle, Sher Afzul. Nizam at once hurried to Chitral; and Sher Afzul fled to Cabul, Nizam becoming the head of the state or, as it was called, Mehtar. Being weak, he asked for a political officer to reside in his territory; and Captain Younghusband, with an escort of Sikhs, was accordingly sent to Mastuj, a fort in Upper Chitral.

However, in November Nizam was also murdered, by a younger brother, Amir. Amir hurried to Chitral, and demanded recognition from Lieutenant Gurdon; who was, at the time, acting as assistant British agent. He replied that he had no power to grant recognition, until he was instructed by the government in India. Amir thereupon stopped his letters, and for a long time he was in imminent danger, as he had only an escort of eight Sikhs.

On the 8th of January, fifty men of the 14th Sikhs marched down from Mastuj and, on the 1st of February, Mr. Robertson, the British agent, arrived from Gilgit. He had with him an escort of two hundred and eighty men of the 4th Kashmir Rifles, and thirty-three Sikhs; and was accompanied by three European officers. When he arrived he heard that Umra Khan had, at the invitation of Amir, marched into Chitral; but that his progress had been barred by the strong fort of Drosh. As the Chitralis hate the Pathans, they were not inclined to yield to the orders of Amir to surrender the fort, and were consequently attacked. The place, however, was surrendered by the treachery of the governor. Amir then advanced, and was joined by Sher Afzul.

Mr. Robertson wrote to Amir Khan, saying that he must leave the Chitral territory. Amir paid no attention to the order, and Mr. Robertson reported this to the government of India. They issued, in March, 1895, a proclamation warning the Chitralis to abstain from giving assistance to Amir Khan, and intimating that a force sufficient to overcome all resistance was being assembled; but that as soon as it had attained its object, it would be withdrawn.

The Chitralis, who now preferred Sher Afzul to Amir, made common cause with the former. Mr. Robertson learned that men were already at work, breaking up the road between Chitral and Mastuj; and accordingly moved from the house he had occupied to the fort, which was large enough to receive the force with him.

On the 1st of March, all communications between Mr. Robertson and Mastuj had ceased; and troops were at once ordered to assemble, to march to his relief. It was clearly impossible for our agent to retire as, in order to do so, he would have to negotiate several terrible passes, where a mere handful of men could destroy a regiment. Thus it was that the Pioneers had been ordered to break up their cantonment, and advance with all speed to Gilgit.

Hostilities had already begun. A native officer had started, with forty men and sixty boxes of ammunition, for Chitral; and had reached Buni, when he received information that his advance was likely to be opposed. He accordingly halted and wrote to Lieutenant Moberley, special duty officer with the Kashmir troops in Mastuj. The local men reported to Moberley that no hostile attack upon the troops was at all likely but, as there was a spirit of unrest in the air, he wrote to Captain Ross, who was with Lieutenant Jones, and requested him to make a double march into Mastuj. This Captain Ross did and, on the evening of the 4th of March, started to reinforce the little body of men that was blocked at Buni.

On the same day a party of sappers and miners, under Lieutenants Fowler and Edwards, also marched forward to Mastuj. When Captain Ross arrived at Buni he found that all was quiet, and he therefore returned to Mastuj, with news to that effect. The party of sappers were to march, the next morning, with the ammunition escort.

On the evening of that day a note was received from Lieutenant Edwards, dated from a small village two miles beyond Buni, saying that he heard that he was to be attacked in a defile, a short distance away. He started with a force of ninety-six men, in all. They carried with them nine days' rations, and one hundred and forty rounds of ammunition.

Captain Ross at once marched for Buni, and arrived there the same evening. Here he left a young native officer and thirty-three rank and file while, with Lieutenant Jones and the rest of his little force, he marched for Reshun, where Lieutenant Edwards' party were detained. They halted in the middle of the day; and arrived, at one o'clock, at a hamlet halfway to Reshun.

Shortly after starting, they were attacked. Lieutenant Jones, one of the few survivors of the party, handed in the following report of this bad business.

"Half a mile after leaving Koragh the road enters a narrow defile. The hills on the left bank consist of a succession of large stone shoots, with precipitous spurs in between. The road at the entrance to the defile, for about one hundred yards, runs quite close to the river; after that it lies along a narrow maidan, some thirty or forty yards in width, and is on the top of the river bank, which is here a cliff. This continues for about half a mile, then it ascends a steep spur.

"When the advanced party reached about halfway up this spur, it was fired on from a sangar which had been built across the road and, at the same time, men appeared on all the mountain tops and ridges, and stones were rolled down all the shoots. Captain Ross, who was with the advanced guard, fell back on the main body. All the coolies dropped their loads and bolted, as soon as the first shot was fired. Captain Ross, after looking at the enemy's position, decided to fall back upon Koragh; as it would have been useless to go on to Reshun, leaving an enemy in such a position behind us."

Captain Ross ordered Lieutenant Jones to fall back with ten men, seize the lower end of the defile, and cover the retreat. No fewer than eight of his men were wounded, as he fell back. Captain Ross, on hearing this, ordered him to return, and the whole party took refuge in two caves, it being the intention of their commander to wait there until the moon rose, and then try to force his way out.

But when they started, they were assailed from above with such a torrent of rocks that they again retired to the caves. They then made an attempt to get to the top of the mountain, but their way was barred by a precipice; and they once more went back to the cave, where they remained all the next day.

It was then decided to make an attempt to cut their way out. They started at two in the morning. The enemy at once opened fire, and many were killed, among them Captain Ross himself. Lieutenant Jones with seventeen men reached the little maidan, and there remained for some minutes, keeping up a heavy fire on the enemy on both banks of the river, in order to help more men to get through.

Twice the enemy attempted to charge, but each time retired with heavy loss. Lieutenant Jones then again fell back, two of his party having been killed and one mortally wounded, and the lieutenant and nine sepoys wounded. When they reached Buni they prepared a house for defence, and remained there for seven days until reinforcements came up.