- Рейтинг Литрес:4.2

Полная версия:

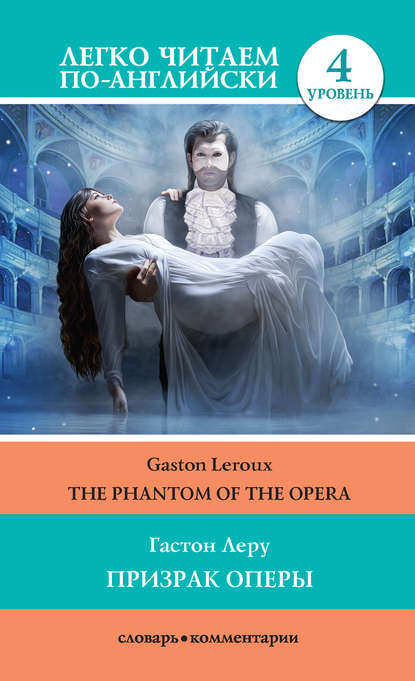

Гастон Леру Призрак оперы / The Phantom of the Opera

- + Увеличить шрифт

- - Уменьшить шрифт

Гастон Леру / Gaston Leroux

Призрак оперы / The Phantom of the Opera

© Матвеев С.А., адаптация текста, комментарий, словарь, 2019

© ООО «Издательство АСТ»

Prologue

The Opera ghost really existed. He was not, as was long believed, a creature of the imagination of the artists, the superstition of the managers, or a product of the absurd and impressionable brains of the young ladies and their mothers. Yes, he existed in flesh and blood.

I began to study the archives of the National Academy of Music[1]. The events do not date more than thirty years back. The truth was slow to enter my mind, at last, I received the proof that my presentiments had not deceived me, and I was rewarded for all my efforts on the day when I acquired the certainty that the Opera ghost was more than a mere shade.

On that day, I had spent long hours in the library. I had just left the library in despair, when I met the delightful acting-manager [2]of our National Academy, who was chatting with a lively old man, to whom he introduced me gaily. The acting-manager knew all about my investigations and how eagerly and unsuccessfully I had been trying to discover the whereabouts of the examining magistrate [3]M. Faure[4]. Nobody knew what had become of him, alive or dead; and here he was back from Canada, where he had spent fifteen years, and the first thing he had done, on his return to Paris, was to come to the Opera. The old man was M. Faure himself.

We spent an evening together and he told me the whole Chagny [5]case as he had understood it at the time. But he could not tell me what became of Christine Daae [6]or the viscount. When I mentioned the ghost, he only laughed. He had listened to the evidence of a witness who declared that he had often met the ghost. This witness was none other than the man whom all Paris called the “Persian.” The magistrate took him for a visionary.

I was interested by this story of the Persian. I wanted to find this valuable and eccentric witness. My luck began to improve and I discovered him in his little flat in the Rue de Rivoli[7], where he had lived ever since and where he died five months after my visit. The Persian had told me all that he knew about the ghost and had handed me the proofs of the ghost’s existence—including the strange correspondence of Christine. I was no longer able to doubt. No, the ghost was not a myth!

I went into the past history of the Persian and found that he was an upright man, incapable of inventing a story.

So, with my papers in hand, I went over the ghost’s vast domain, the huge building which he had made his kingdom. Later, when digging in the substructure of the Opera, the workmen found a corpse. I was at once able to prove that this corpse was that of the Opera ghost.

But we will return to the corpse and what ought to be done with it. For the present, I must conclude this very necessary introduction by thanking M. Mifroid (who was the commissary of police called in for the first investigations after the disappearance of Christine Daae), M. Remy, the late secretary, M. Mercier, the late acting-manager, M. Gabriel, the late chorus-master[8], and more particularly Mme. la Baronne de Castelot-Barbezac[9], who was once the “little Meg[10]” of the story (and who is not ashamed of it). All these were of the greatest assistance to me; and, thanks to them, I shall be able to reproduce those hours of sheer love and terror, in their smallest details, before the reader’s eyes.

Chapter I

It was the evening on which MM. Debienne and Poligny[11], the managers of the Opera, were giving a last gala performance to mark their retirement. Suddenly the dressing-room of La Sorelli[12], one of the principal dancers, was invaded by half-a-dozen young ladies of the ballet, who had come up from the stage. They rushed in amid great confusion. Sorelli, who wished to be alone for a moment, looked around angrily at the mad and tumultuous crowd. It was the little girl who gave the explanation in a trembling voice:

“It’s the ghost!” And she locked the door.

Sorelli was very superstitious. She shuddered when she heard the little girl speak of the ghost, called her a “silly little fool” and then asked for details:

“Have you seen him?”

“As plainly as I see you now!” said the little girl: “If that’s the ghost, he’s very ugly!”

“Oh, yes!” cried the chorus of ballet-girls.

And they all began to talk together. The ghost had appeared to them in the shape of a gentleman in dress-clothes, who had suddenly stood before them in the passage. He seemed to have come straight through the wall.

“Pooh!” said one of them. “You see the ghost everywhere!”

And it was true. For several months, there had been nothing discussed at the Opera but this ghost in dress-clothes. He was like a shadow, he spoke to nobody, to him nobody dared speak and he vanished, no one knowing how or where. He made no noise in walking. When he did not show himself, he betrayed his presence by accident, comic or serious.

After all, who had seen him? You meet so many men dressed in black at the Opera who are not ghosts. But this suit had a peculiarity of its own. It covered a skeleton. At least, so the ballet-girls said. And, of course, it had a death’s head[13].

Was all this serious? The truth is that the idea of the skeleton came from the description of the ghost given by Joseph Buquet[14], the chief scene-shifter[15], who had really seen the ghost. He had seen him for a second—for the ghost had run away. Joseph said:

“He is extraordinarily thin. His eyes are very deep, you just see two big black holes, as in a dead man’s skull. His skin, which is stretched across his bones like a drumhead, is not white, but yellow. His nose is so little worth talking about that you can’t see it; and the absence of that nose is a horrible thing to look at. All the hair he has is three or four long dark locks on his forehead and behind his ears.”

This chief scene-shifter was a serious, sober, steady man. His words were received with interest and amazement; and soon there were other people to say that they too had met a man with a death’s head on his shoulders. And then, one after the other, there came a series of incidents so curious and so inexplicable that the very shrewdest people began to feel uneasy.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «Литрес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на Литрес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Примечания

1

National Academy of Music – Национальная академия музыки (французский оперный театр в Париже)

2

acting-manager – администратор

3

examining magistrate – судебный следователь

4

Faure – Фор

5

Chagny – Шаньи

6

Christine Daae – Кристина Даэ

7

Rue de Rivoli – улица Риволи

8

chorus-master – хормейстер

9

Mme. la Baronne de Castelot-Barbezac – баронесса де Кастело-Барбезак

10

little Meg – крошка Мег

11

MM. Debienne and Poligny – господа Дебьенн и Полиньи

12

the dressing-room of La Sorelli – гримёрная Сорелли

13

death’s head – череп

14

Joseph Buquet – Жозеф Бюке

15

the chief scene-shifter – старший машинист сцены