Dodd George

The History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8

Bareilly, we have just seen, was one of the towns from which fugitive ladies were sent for safety to Nynee Tal; and now the town of Boodayoun, on the road from Agra to Bareilly, comes for notice under similar conditions. Considering that the course of public events often receives illustration of a remarkable kind from the experience of single individuals, we shall treat the affairs of Boodayoun in connection with the strange adventures of one of the Company’s civil servants – adventures not so deeply distressing as those of the fugitives from Delhi, but continued during a much longer period, and bringing to light a much larger number of facts connected with the feelings and position of the natives in the disturbed districts. The wanderer, Mr Edwards, collector of the Boodayoun district, was more than three months in reaching Cawnpore from Boodayoun – a distance scarcely over a hundred miles by road. About the middle of May, the districts on both sides of the Ganges becoming very disturbed, Mr Edwards sent his wife and child for refuge to Nynee Tal. He was the sole European officer in charge of the Boodayoun district, and felt his anxieties deepen as rumours reached him of disturbances in other quarters. At the end of the month, news of the revolt at Bareilly added to his difficulties; for the mutineers and a band of liberated prisoners were on their way from that place to Boodayoun. Mr Edwards expresses his opinion that the mutiny was aggravated by the laws, or the course adopted by the civil courts, concerning landed property. Landed rights and interests were sold by order of the courts for petty debts; they were bought by strangers, who had no particular sympathy with the people; and the old landowners, regarded with something like affection by the peasantry, were thrown into a discontented state. Evidence was soon afforded that these dispossessed landowners joined the mutineers, not from a political motive, but to seize hold of their old estates during a time of turmoil and violence. ‘The danger now is, that they can never wish to see the same government restored to power; fearing, as they naturally must, that they will have again to give up possession of their estates.’ This subject, of landed tenure in India, will call for further illustration in future pages, in relation to the condition of the people.

Narrowly escaping peril himself, Mr Edwards, on the 1st of June, saw that flight was his only chance. There were two English indigo-planters in the neighbourhood, together with another European, who determined to accompany him wherever he went, thinking their safety would be thereby increased. This embarrassed him, for friendly natives who might shelter one person, would probably hesitate to receive four; and so it proved, on several occasions. He started off on horseback, accompanied by the other three, and by a faithful Sikh servant, Wuzeer Singh, who never deserted him through all his trials. The worldly wealth of Mr Edwards at this moment consisted of the clothes on his back, a revolver, a watch, a purse, and a New Testament. During the first few days they galloped from village to village, just as they found the natives favourable or hostile; often forced to flee when most in need of food and rest. They crossed the Ganges two or three times, tracing out a strange zigzag in the hope of avoiding dangers. The wanderers then made an attempt to reach Futteghur. They suffered much, and one life was lost, in this attempt; the rest, after many days, reached Futteghur, where Mr Probyn was the Company’s collector. Native troops were mutinying, or consulting whether to mutiny; Europeans were departing; and it soon became evident that Futteghur would no longer be a place of safety either for Probyn or for Edwards. Flight again became necessary, and under more anxious circumstances, for a lady and four children were to be protected; but how to flee, and whither, became anxious questions. Day after day passed, before a friendly native could safely plan an escape for them by boat; enemies and marauders were on every side; and at last the danger became so imminent that it was resolved to cross the Ganges, and seek an asylum in a very desolate spot, out of the way of the mutineers. Here was presented a curious exemplification of ‘lucky’ and ‘unlucky’ days as viewed by the natives. ‘A lucky day having been found for our start,’ says Mr Edwards, ‘we were to go when the moon rose; but this moon-rise was not till three o’clock on the morning after that fixed for the start. This the Thakoors were not at first aware of. I was wakened about eleven o’clock by one of them, who said that the fact had just come to his knowledge, and that it was necessary that something belonging to us should start at once, as this would equally secure the lucky influence of the day, even though we ourselves should not start till next morning. A table-fork was accordingly given him, with which he went off quite satisfied, and which was sent by a bearer towards the village we were to proceed to.’ Under the happy influence of this table-fork, the wanderers set forth by night, Mrs Probyn and her children riding on an elephant, and the men walking on roads almost impassable with mud. They reached the stream; they crossed in a boat; they walked some distance amid torrents of rain, Mr Edwards ‘carrying poor baby;’ and then they reached the village, Runjpoonah, destined for their temporary home. What a home it was! ‘The place intended for the Probyns was a wretched hovel occupied by buffaloes, and filthy beyond expression, the smell stifling, and the mud and dirt over our ankles. My heart sank within me as I laid down my little charge on a charpoy.’ By the exercise of ingenuity, an extemporaneous chamber was fitted up in the roof. During a long sojourn here in the rainy season, Mr Edwards wrote a letter to his wife at Nynee Tal, under the following odd circumstances: ‘I had but a small scrap of paper on which to write my two notes, and just the stump of a lead-pencil: we had neither pens nor ink. In the middle of my writing, the pencil-point broke; and when I commenced repointing it, the whole fell out, there being just a speck of lead left. I was in despair; but was fortunately able to refix the atom, and to finish two short notes – about an inch square each: it was all the man could conceal about him. I then steeped the notes in a little milk, and put them out to dry in the sun. At once a crow pounced on one and carried it off, and I of course thought it was lost for ever. Wuzeer Singh, however, saw and followed the creature, and recovered the note after a long chase.’ Several weeks passed; ‘poor baby’ died; then an elder child – both sinking under the privations they had had to endure: their anxious mother, with all her tender solicitude, being unable further to preserve them. Mr Edwards, who was one of those that thought the annexation of Oude an unwise measure, said, in relation to a rumour that Oude had been restored to its king: ‘I would rejoice at such an equitable measure at another time; but now it would be, if true, a sign of a falling cause and of great weakness, which is I fear our real case.’ On another occasion, he heard ‘more rumours that the governor-general and the King of Oude had arrived at Cawnpore; and that Oude is then formally to be made over to the king.’ Whether Oudians or not, everywhere he found the Mohammedans more hostile to the British than the Hindoos; and in some places the two bodies of religionists fought with each other. After many more weeks of delays and disappointments, the fugitives were started off down the Ganges to Cawnpore. In effecting this start, the ‘lucky-day’ principle was again acted on. ‘The astrologer had fixed an hour for starting. As it was not possible for us to go at the fortunate moment and secure the advantage, a shirt of mine and some garments of those who were to accompany me, were forwarded to a village some way on the road, which is considered equivalent to ourselves starting.’ Half-a-dozen times on their voyage were they in danger of being shot by hostile natives on shore; but the fidelity and tact of the natives who had befriended them carried them through all their perils. At length they reached Cawnpore on the 1st of September, just three calendar months after Mr Edwards took his hasty departure from Boodayoun.

This interesting train of adventures we have followed to its close, as illustrating so many points connected with the state of India at the time; but now attention must be brought back to the month of May.

West of the Rohilcund district, and northwest of Allygurh and its neighbouring cluster of towns, lie Meerut and Delhi, the two places at which the atrocities were first manifested. Meerut, after the departure of the three mutinous regiments on the night of the 10th of May, and the revolt of the Sappers and Miners a few days afterwards, remained unmolested. Major-general Hewett was too strong in European troops to be attacked, although his force took part in many operations against the rebels elsewhere. Several prisoners, proved to have been engaged in the murderous work of the 10th, were hanged. On the other hand, many sowars of the 3d native cavalry, instead of going to Delhi, spread terror among the villagers near Meerut. One of the last military dispatches of the commander-in-chief was to Hewett, announcing his intention to send most of his available troops from Kurnaul by Bhagput and Paniput, to Delhi, and requesting Hewett to despatch from Meerut an auxiliary force. This force he directed should consist of two squadrons of carabiniers, a wing of the 60th Rifles, a light field-battery, a troop of horse-artillery, a corps of artillerymen to work the siege-train, and as many sappers as he could depend upon. General Anson calculated that if he left Umballa on the 1st of June, and if Hewett sent his force from Meerut on the 2d, they might meet at Bhagput on the 5th, when a united advance might be made upon Delhi; but, as we shall presently see, the hand of death struck down the commander-in-chief ere this plan could be carried out; and the force from Meerut was placed at the disposal of another commander, under circumstances that will come under notice in their proper place.

Delhi, like Cawnpore, must be treated apart from other towns. The military proceedings connected with its recapture were so interesting, and carried on over so long a period; it developed resources so startlingly large among the mutineers, besieging forces so lamentably small on the part of the British – that the whole will conveniently form a subject complete in itself, to be treated when collateral events have been brought up to the proper level. Suffice it at present to say, that the mutineers over the whole of the north of India looked to the retention of Delhi as their great stronghold, their rock of defence; while the British saw with equal clearness that the recapture of that celebrated city was an indispensable preliminary to the restoration of their prestige and power in India. All the mutineers from other towns either hastened to Delhi, or calculated on its support to their cause, whatever that cause may have been; all the available British regiments, on the other hand, few indeed as they were, either hastened to Delhi, or bore it in memory during their other plans and proceedings.

Just at the time when the services of a military commander were most needed in the regions of which Agra is the centre, and when it was necessary to be in constant communication with the governor-general and authorities, General Anson could not be heard of; he was supposed at Calcutta to be somewhere between Simla and Delhi; but dâks and telegraphs had been interfered with, and all remained in mystery as to his movements. Lawrence at Lucknow, Ponsonby at Benares, Wheeler at Cawnpore, Colvin at Agra, Hewett at Meerut, other commanders at Allahabad, Dinapoor, and elsewhere – all said in effect: ‘We can hold our own for a time, but not unless Delhi be speedily recaptured. Where is the commander-in-chief?’ Viscount Canning sent messages in rapid succession, during the second half of the month of May, entreating General Anson to bring all his power to bear on Delhi as quickly as possible. Duplicate telegrams were sent by different routes, in hopes that one at least might reach its destination safely; and every telegram told the same story – that British India was in peril so long as Delhi was not in British hands, safe from murderers and marauders. Major-general Sir Henry Barnard, military commander of the Umballa district, received telegraphic news on the 11th of May of the outrages at Meerut and Delhi; and immediately sent an aid-de-camp to gallop off with the information to General Anson at Simla, seventy or eighty miles distant. The commander-in-chief at once hastened from his retirement among the hills. Simla, as was noticed in a former page, is one of the sanataria for the English in India, spots where pure air and moderate temperature restore to the jaded body some of the strength, and to the equally jaded spirits some of the elasticity, which are so readily lost in the burning plains further south. The poorer class among the Europeans cannot afford the indulgence, for the cost is too great; but the principal servants of the Company often take advantage of this health-restoring and invigorating climate – where the average temperature of the year is not above 55° F. The question has been frequently discussed, and is not without cogency, whether the commander-in-chief acted rightly in remaining at that remote spot during the first twenty weeks in the year, when so many suspicious symptoms were observable among the native troops at Calcutta, Dumdum, Barrackpore, Berhampore, Lucknow, Meerut, and Umballa. He could know nothing of the occurrences at those places but what the telegraphic wires and the postal dâks told him; nevertheless, if they told him the truth, and all the truth, it seems difficult to understand, unless illness paralysed his efforts, why he, the chief of the army, remained quiescent at a spot more than a thousand miles from Calcutta.

Startled by the news, the commander-in-chief quitted Simla, and hastened to Umballa, the nearest military station on the great Indian highway. It then became sensibly felt, both by Anson and Barnard, how insufficient were the appliances at their disposal. The magazines at Umballa were nearly empty of stores and ammunition; the reserve artillery-wagons were at Phillour, eighty miles away; the native infantry were in a very disaffected state; the European troops were at various distances from Umballa; the commissariat officers declared it to be almost impossible to move any body of troops, in the absence of necessary supplies for a column in the field; and the medical officers dwelt on the danger of marching troops in the hot season, and on the want of conveyance for sick and wounded. In short, almost everything was wanting, necessary for the operations of an army. The generals set to work, however; they ordered the 2d European Fusiliers to hasten from Subathoo to Umballa; the Nusseree Battalion to escort a siege-train and ammunition from Phillour to Umballa; six companies of the Sappers and Miners to proceed from Roorkee to Meerut; and the 4th Irregular Cavalry to hold themselves in readiness at Hansi. Anson at the same time issued the general order, already adverted to, inviting the native regiments to remain true to their allegiance, explaining the real facts concerning the cartridges, and reiterating the assurances of non-intervention with the religious and caste scruples of the men. On the 17th there were more than seven regiments of troops at Umballa – namely, the Queen’s 9th Lancers, the 4th Light Cavalry Lancers, the Queen’s 75th foot, the 1st and 2d European Fusiliers, the 5th and 60th native infantry, and two troops of European horse-artillery; but the European regiments were all far short of their full strength. Symptoms soon appeared that the 5th and 60th native infantry were not to be relied upon for fidelity; and General Anson thereupon strengthened his force at Umballa with such European regiments as were obtainable. He was nevertheless in great perplexity how to shape his course; for so many wires had been cut and so many dâks stopped, that he knew little of the progress of events around Delhi and Agra. Being new to India and Indian warfare, also, and having received his appointment to that high command rather through political connections than in reference to any experience derived from Asiatic campaigning, he was dependent on those around him for suggestions concerning the best mode of grappling with the difficulties that were presented. These suggestions, in all probability, were not quite harmonious; for it has long been known that, in circumstances of emergency, the civil and military officers of the Company, viewing occurrences under different aspects or from different points of view, often arrived at different estimates as to the malady to be remedied, and at different suggestions as to the remedy to be applied. At the critical time in question, however, all the officers, civil as well as military, assented to the conclusion that Delhi must be taken at any cost; and on the 21st of May, the first division of a small but well-composed force set out from Umballa on the road to Delhi. General Anson left on the 25th, and arrived on the 26th at Kurnaul, to be nearer the scene of active operations; but there death carried him off. He died of cholera on the next day, the 27th of May.

With a governor-general a thousand miles away, the chief officers at and near Kurnaul settled among themselves as best they could, according to the rules of the service, the distribution of duties, until official appointments could be made from Calcutta. Major-general Sir Henry Barnard became temporary commander, and Major-general Reid second under him. When the governor-general received this news, he sent for Sir Patrick Grant, a former experienced adjutant-general of the Bengal army, from Madras, to assume the office of commander-in-chief; but the officers at that time westward of Delhi – Barnard, Reid, Wilson, and others – had still the responsibility of battling with the rebels. Sir Henry Barnard, as temporary chief, took charge of the expedition to Delhi – with what results will be shewn in the proper place.

The regions lying west, northwest, and southwest of Delhi have this peculiarity, that they are of easier access from Bombay or from Kurachee than from Calcutta. Out of this rose an important circumstance in connection with the Revolt – namely, the practicability of the employment of the Bombay native army to confront the mutinous regiments belonging to that of Bengal. It is difficult to overrate the value of the difference between the two armies. Had they been formed of like materials, organised on a like system, and officered in a like ratio, the probability is that the mutiny would have been greatly increased in extent – the same motives, be they reasonable or unreasonable, being alike applicable to both armies. Of the degree to which the Bombay regiments shewed fidelity, while those of Bengal unfurled the banner of rebellion, there will be frequent occasions to speak in future pages. The subject is only mentioned here to explain why the western parts of India are not treated in the present chapter. There were, it is true, disturbances at Neemuch and Nuseerabad, and at various places in Rajpootana, the Punjaub, and Sinde; but these will better be treated in later pages, in connection rather with Bombay than with Calcutta as head-quarters. Enough has been said to shew over how wide an area the taint of disaffection spread during the month of May – to break out into something much more terrible in the next following month.

Notes

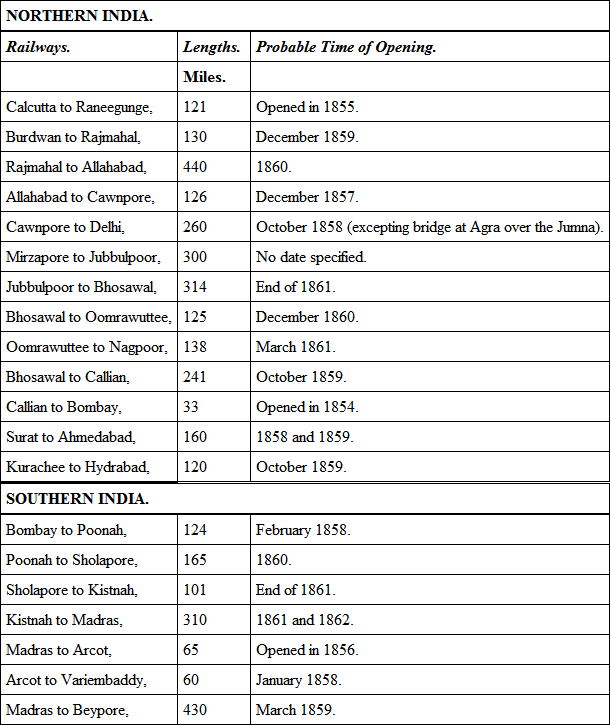

Indian Railways.– An interesting question presents itself, in connection with the subject of the present chapter – Whether the Revolt would have been possible had the railways been completed? The rebels, it is true, might have forced up or dislocated the rails, or might have tampered with the locomotives. They might, on the other hand, if powerfully concentrated, have used the railways for their own purposes, and thus made them am auxiliary to rebellion. Nevertheless, the balance of probability is in favour of the government – that is, the government would have derived more advantage than the insurgents from the existence of railways between the great towns of India. The difficulties, so great as to be almost insuperable, in transporting troops from one place to another, have been amply illustrated in this and the preceding chapters; we have seen how dâk and palanquin bearers, bullocks and elephants, ekahs and wagons, Ganges steamers and native boats, were brought into requisition, and how painfully slow was the progress made. The 121 miles of railway from Calcutta to Raneegunge were found so useful, in enabling the English soldiers to pass swiftly over the first part of their journey, that there can hardly be a doubt of the important results which would have followed an extension of the system. Even if a less favourable view be taken in relation to Bengal and the Northwest Provinces, the advantages would unquestionably have been on the side of the government in the Bombay and Madras presidencies, where disaffection was shewn only in a very slight degree; a few days would have sufficed to send troops from the south of India by rail, viâ Bombay and Jubbulpoor to Mirzapore, in the immediate vicinity of the regions where their services were most needed.

Although the Raneegunge branch of the East Indian Railway was the only portion open in the north of India, there was a section of the main line between Allahabad and Cawnpore nearly finished at the time of the outbreak. This main line will nearly follow the course of the Ganges, from Calcutta up to Allahabad; it will then pass through the Doab, between the Ganges and the Jumna, to Agra; it will follow the Jumna from Agra up to Delhi; and will then strike off northwestward to Lahore – to be continued at some future time through the Punjaub to Peshawur. During the summer of 1857, the East India Company prepared, at the request of parliament, an exact enumeration of the various railways for which engineering plans had been adopted, and for the share-capital of which a minimum rate of interest had been guaranteed by the government. The document gives the particulars of about 3700 miles of railway in India; estimated to cost £30,231,000; and for which a dividend is guaranteed to the extent of £20,314,000, at a rate varying from 4½ to 5 per cent. The government also gives the land, estimated to be worth about a million sterling. All the works of construction are planned on a principle of solidity, not cheapness; for it is expected they will all be remunerative. Arrangements are everywhere made for a double line of rails – a single line being alone laid down until the traffic is developed. The gauge is nine inches wider than the ‘narrow gauge’ of English railways. The estimated average cost is under £9000 per mile, about one-fourth of the English average.

Leaving out of view, as an element impossible to be correctly calculated, the amount of delay arising from the Revolt, the government named the periods at which the several sections of railway would probably be finished. Instead of shewing the particular portions belonging respectively to the five railway companies – the East Indian, the Great Indian Peninsula, the Bombay and Central India, the Sinde, and the Madras – we shall simply arrange the railways into two groups, north and south, and throw a few of the particulars into a tabulated form.

The plans for an Oude railway were drawn up, comprising three or four lines radiating from Lucknow; but the project had not, at that time, assumed a definite form.

’Headman’ of a Village.– It frequently happened, in connection with the events recorded in the present chapter, that the headman of a village either joined the mutineers against the British, or assisted the latter in quelling the disturbances; according to the bias of his inclination, or the view he took of his own interests. The general nature of the village-system in India requires to be understood before the significancy of the headman’s position can be appreciated. Before the British entered India, private property in land was unknown; the whole was considered to belong to the sovereign. The country was divided, by the Mohammedan rulers, into small holdings, cultivated each by a village community under a headman; for which a rent was paid. For convenience of collecting this rent or revenue, zemindars were appointed, who either farmed the revenues, or acted simply as agents for the ruling power. When the Marquis of Cornwallis, as governor-general, made great changes in the government of British India half a century ago, he modified, among other matters, the zemindary; but the collection of revenue remained.

Whether, as some think, villages were thus formed by the early conquerors; or whether they were natural combinations of men for mutual advantage – certain it is that the village-system in the plains of Northern India was made dependent in a large degree on the peculiar institution of caste. ‘To each man in a Hindoo village were appointed particular duties which were exclusively his, and which were in general transmitted to his descendants. The whole community became one family, which lived together and prospered on their public lands; whilst the private advantage of each particular member was scarcely determinable. It became, then, the fairest as well as the least troublesome method of collecting the revenue to assess the whole village at a certain sum, agreed upon by the tehsildar (native revenue collector) and the headman. This was exacted from the latter, who, seated on the chabootra, in conjunction with the chief men of the village, managed its affairs, and decided upon the quota of each individual member. By this means, the exclusive character of each village was further increased, until they have become throughout nearly the whole of the Indian peninsula, little republics; supplied, owing to the regulations of caste, with artisans of nearly every craft, and almost independent of any foreign relations.’14

Not only is the headman’s position and duties defined; but the whole village may be said to be socially organised and parcelled out by the singular operation of the caste principle. Each village manages its internal affairs; taxes itself to provide funds for internal expenses, as well as the revenue due to the state; decides disputes in the first instance; and punishes minor offences. Officers are selected for all these duties; and there is thus a local government within the greater government of the paramount state. One man is the scribe of the village; another, the constable or policeman; a third, the schoolmaster; a fourth, the doctor; a fifth, the astrologer and exorciser; and so of the musician, the carpenter, the smith, the worker in gold or jewels, the tailor, the worker in leather, the potter, the washerman – each considers that he has a prescriptive right to the work in his branch done within the village, and to the payment for that work; and each member of his family participates in this prescriptive right. This village-system is so interwoven with the habits and customs of the Hindoos, that it outlives all changes going on around. Sir T. Metcalfe, who knew India well, said: ‘Dynasty after dynasty tumbles down; revolution succeeds to revolution; Hindoo, Patan, Mogul, Mahratta, Sikh, English, are all masters in turn; but the village community remains the same. In times of trouble they arm and fortify themselves. If a hostile army passes through the country, the village communities collect their cattle within their walls, and let the enemy pass unprovoked. If plunder and devastation be directed against themselves, and the force employed be irresistible, they flee to friendly villages at a distance; but when the storm has passed over, they return and resume their occupations. If a country remain for a series of years the scene of continued pillage and massacre, so that the village cannot be inhabited, the scattered villages nevertheless return whenever the power of peaceable possession revives. A generation may pass away, but the succeeding generation will return. The sons will take the places of their fathers; the same site for their village, the same positions for the houses, the same lands will be reoccupied by the descendants of those who were driven out when the village was depopulated; and it is not a trifling matter that will drive them out, for they will often maintain their post through times of disturbance and convulsion, and acquire strength sufficient to resist pillage and oppression with success. This union of the village communities, each one forming a separate little state in itself, has, I conceive, contributed more than any other cause to the preservation of the people of India through all the revolutions and changes which they have suffered.’15

It is easily comprehensible how, in village communities thus compactly organised, the course of proceeding adopted by the headman in any public exigency becomes of much importance; since it may be a sort of official manifestation of the tendencies of the villagers generally.