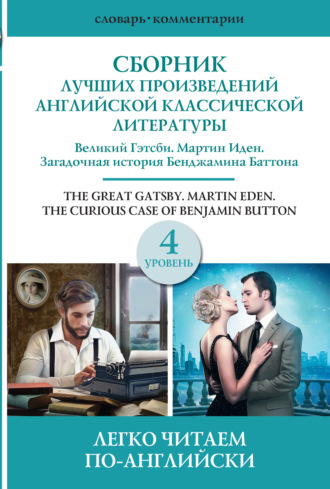

Фрэнсис Скотт Фицджеральд

Сборник лучших произведений американской классической литературы. Уровень 4

“They're such beautiful shirts,” she sobbed, her voice muffled in the thick folds. “It makes me sad because I've never seen such – such beautiful shirts before.”

Daisy put her arm through his abruptly. I began to walk about the room, examining various objects. A large photograph of an elderly man in yachting costume attracted me, hung on the wall over his desk.

“Who's this?”

“That's Mr. Dan Cody[46], old sport. He's dead now. He used to be my best friend years ago.”

There was a small picture of Gatsby, also in yachting costume – taken apparently when he was about eighteen.

“I adore it!” exclaimed Daisy.

After the house, we were to see the grounds and the swimming pool, and the hydroplane and the midsummer flowers – but outside Gatsby's window it began to rain again so we stood in a row looking at the corrugated surface of the Sound.

Almost five years! His hand took hold of hers and as she said something low in his ear he turned toward her with a rush of emotion. They had forgotten me, Gatsby didn't know me now at all. I looked once more at them and went out of the room, leaving them there together.

Chapter 6

James Gatz[47] – that was his name. He had changed it at the age of seventeen and at the specific moment – when he saw Dan Cody's yacht. It was James Gatz who had been loafing along the beach that afternoon, but it was already Jay Gatsby who borrowed a row-boat and informed Cody that a wind might catch him and break him up in half an hour.

His parents were unsuccessful farm people – his imagination had never really accepted them as his parents at all. So he invented Jay Gatsby, and to this conception he was faithful to the end.

Dan Cody was fifty years old then, he was a millionaire, and an infinite number of women tried to separate him from his money. To the young Gatz the yacht represented all the beauty and glamour in the world. Cody asked him a few questions and found that he was clever, and extravagantly ambitious. A few days later he bought him a blue coat, six pairs of white trousers and a yachting cap.

He was employed as a steward, skipper, and secretary. The arrangement lasted five years during which the boat went three times around the continent. In Boston Dan Cody died.

He told me all this very much later.

For several weeks I didn't see him or hear his voice on the phone. But finally I went over to his house one Sunday afternoon. I hadn't been there two minutes[48] when somebody brought Tom Buchanan in for a drink.

“I'm delighted to see you,” said Gatsby. “Sit right down. Have a cigarette or a cigar.” He walked around the room quickly, ringing bells. “I'll have something to drink for you in just a minute.”

He was profoundly affected by the fact that Tom was there.

“I believe we've met somewhere before, Mr. Buchanan. I know your wife,” continued Gatsby.

“That so?[49]“

Tom turned to me.

“You live near here, Nick?”

“Next door.”

“That so?”

Tom was evidently perturbed at Daisy's running around alone, for on the following Saturday night he came with her to Gatsby's party. Daisy's voice was playing murmurous tricks in her throat.

“These things excite me SO,” she whispered.

“Look around,” suggested Gatsby. “You must see the faces of many people you've heard about.”

Daisy and Gatsby danced. I remember being surprised[50] by his graceful, conservative fox-trot – I had never seen him dance[51] before. Then they came to my house and sat on the steps for half an hour while at her request I remained watchfully in the garden.

The party was over. I sat on the front steps with them while they waited for their car. It was dark here in front of the house.

“Who is this Gatsby anyhow?” demanded Tom suddenly. “Some big bootlegger?”

“Where'd you hear that?” I inquired.

“I didn't hear it. I imagined it. A lot of these newly rich people are just big bootleggers, you know.”

“Not Gatsby,” I said shortly.

He was silent for a moment.

“I'd like to know who he is and what he does,” insisted Tom. “And I think I'll make a point of finding out[52].”

“I can tell you right now,” answered Daisy. “He owned some drug stores, a lot of drug stores. He built them up himself.”

The dilatory limousine came rolling up the drive.

“Good night, Nick,” said Daisy.

Gatsby was silent.

“I feel far away from her,” he said.

He wanted nothing less of Daisy than that she should go to Tom and say, “I never loved you.”

“You can't repeat the past.”

“Can't repeat the past?” he cried incredulously. “Why of course[53] you can!”

He looked around him wildly, as if the past were lurking here in the shadow of his house.

“I'm going to fix everything just the way it was before,” he said, nodding determinedly.

Chapter 7

It was when curiosity about Gatsby was at its highest that the lights in his house failed to go on one Saturday night – and, as obscurely as it had begun, his career as Trimalchio[54] was over.

Only gradually did I become aware that the automobiles which turned expectantly into his drive stayed for just a minute and then drove sulkily away. Wondering if he were sick I went over to find out – an unfamiliar butler with a villainous face squinted at me suspiciously from the door.

“Is Mr. Gatsby sick?”

“Nope.” After a pause he added “sir” in a dilatory, grudging way.

“I hadn't seen him around, and I was rather worried. Tell him Mr. Carraway came over.”

“Who?” he demanded rudely.

“Carraway.”

“Carraway. All right, I'll tell him.” Abruptly he slammed the door.

My Finn informed me that Gatsby had dismissed every servant in his house a week ago and replaced them with half a dozen others, who never went into West Egg Village to be bribed by the tradesmen, but ordered moderate supplies over the telephone. The grocery boy reported that the kitchen looked like a pigsty, and the general opinion in the village was that the new people weren't servants at all.

Next day Gatsby called me on the phone.

“Going away?” I inquired.

“No, old sport.”

“I hear you fired all your servants.”

“I wanted somebody who wouldn't gossip. Daisy comes over quite often – in the afternoons.”

He was calling up at Daisy's request – would I come to lunch at her house tomorrow? Miss Baker would be there. Half an hour later Daisy herself telephoned and seemed relieved to find that I was coming. I couldn't believe that they would choose this occasion for a scene[55].

The next day I stood before the Buchanans' house.

“Madame expects you in the salon!” cried the servant.

Gatsby stood in the center of the crimson carpet and gazed around with fascinated eyes. Daisy watched him and laughed, her sweet, exciting laugh.

We were silent. Tom opened the door, blocked out its space for a moment with his thick body, and hurried into the room.

“Mr. Gatsby! I'm glad to see you, sir… Nick…”

“Make us a cold drink,” cried Daisy.

As he left the room again she got up and went over to Gatsby and pulled his face down kissing him on the mouth.

“You know I love you,” she murmured. “I don't care!”

Daisy sat back upon the couch.

“It's so hot,” said Daisy. “Let's all go to town! Who wants to go to town?”

“Let's go! Come on, come on!” said Tom.

“I can't say anything in his house, old sport,” said Gatsby to me. “Her voice is full of money,” he said suddenly.

That was it. I'd never understood before. It was full of money.

“Shall we all go in my car?” suggested Gatsby.

“Well, you take mine and let me drive your car to town,” offered Tom.

“I don't think there's much gas,” said Gatsby.

Daisy walked close to Gatsby, touching his coat with her hand. Jordan and Tom and I got into the front seat of Gatsby's car.

“You think I'm pretty dumb, don't you?” suggested Tom. “Perhaps I am, but I have a – almost a second sight, sometimes. I've made a small investigation of this fellow,” he continued. “I'd been making a small investigation of his past.”

“And you found he was an Oxford man,” said Jordan helpfully.

“An Oxford man!” He was incredulous. “Like hell he is![56]”

“Listen, Tom. Why did you invite him to lunch?” demanded Jordan.

“Daisy invited him; she knew him before we were married!”

The car began to make strange sounds. I remembered Gatsby's caution about gasoline.

“There's a garage right here,” objected Jordan.

Tom threw on both brakes impatiently and we came to a dusty stop under Wilson's sign.

“Let's have some gas!” cried Tom roughly. “What do you think we stopped for – to admire the view?”

“I'm sick,” said Wilson without moving. “I've been sick all day.”

“Well, shall I help myself?” Tom demanded.

With an effort Wilson left the shade and unscrewed the cap of the tank. In the sunlight his face was green.

“I've been here too long. I want to get away. My wife and I want to go west.”

“Your wife does!” exclaimed Tom.

“She's been talking about it for ten years. I'm going to get her away. I learned something,” remarked Wilson. “That's why I want to get away.”

Tom was feeling the hot whips of panic. His wife and his mistress were slipping from his control.

“You follow me to the south side of Central Park, in front of the Plaza,” said he.

Several times he turned his head and looked back for their car. I think he was afraid they would dart down a side street and out of his life forever.

We all decided to take the suite in the Plaza Hotel.

The room was large and stifling. Daisy went to the mirror and stood with her back to us, fixing her hair.

“It's a great suite,” whispered Jordan respectfully and every one laughed.

“Open another window,” commanded Daisy, without turning around.

“The thing to do is to forget about the heat,” said Tom impatiently. “You make it ten times worse by crabbing about it.”

He unrolled the bottle of whiskey from the towel and put it on the table.

“Why not let her alone, old sport?” remarked Gatsby. “You're the one that wanted to come to town.”

There was a moment of silence.

“Where'd you pick that up – this 'old sport'?”

“Now see here, Tom,” said Daisy, turning around from the mirror, “if you're going to make personal remarks I won't stay here a minute.”

“By the way, Mr. Gatsby, I understand you're an Oxford man.”

“Not exactly.”

“Oh, yes. It was in nineteen-nineteen, I only stayed five months. That's why I can't really call myself an Oxford man.”

Daisy rose, smiling faintly, and went to the table.

“Open the whiskey, Tom,” she ordered. “Then you won't seem so stupid to yourself.”

“Wait a minute,” said Tom, “I want to said Mr. Gatsby some words.”

“Go on,” Gatsby said politely.

“I suppose the latest thing is to sit back and let Mr. Nobody from Nowhere[57] make love to your wife!” “I know I'm not very popular. I don't give big parties.”

Angry as I was[58], I was tempted to laugh whenever he opened his mouth.

“I've got something to tell YOU, old sport, – ” began Gatsby. But Daisy interrupted helplessly.

“Please don't! Please let's all go home. Why don't we all go home?”

“That's a good idea.” I got up. “Come on, Tom. Nobody wants a drink.”

“I want to know what Mr. Gatsby has to tell me.”

“Your wife doesn't love you,” said Gatsby. “She's never loved you. She loves me.”

“You must be crazy!” exclaimed Tom automatically.

Gatsby sprang to his feet, vivid with excitement.

“She never loved you, do you hear?” he cried. “She only married you because I was poor and she was tired of waiting for me. It was a terrible mistake, but in her heart she never loved any one except me!”

At this point Jordan and I tried to go but Tom and Gatsby insisted with competitive firmness that we remain – as though neither of them had anything to conceal and it would be a privilege to partake vicariously of their emotions.

“Sit down, Daisy.” Tom's voice groped unsuccessfully for the paternal note. “What's been going on? I want to hear all about it.”

“I told you what's going on,” said Gatsby. “Going on for five years – and you didn't know.”

Tom turned to Daisy sharply.

“You've been seeing this fellow[59] for five years?”

“Not seeing,” said Gatsby. “No, we couldn't meet. But both of us loved each other all that time, old sport, and you didn't know. I used to laugh sometimes – ” but there was no laughter in his eyes, “to think that you didn't know.”

“Oh – that's all.” Tom tapped his thick fingers together like a clergyman and leaned back in his chair.

“You're crazy!” he exploded. “I can't speak about what happened five years ago, because I didn't know Daisy then – and I'll be damned if I see how you got within a mile of her unless you brought the groceries to the back door. But all the rest of that's a God Damned lie. Daisy loved me when she married me and she loves me now.”

“No,” said Gatsby, shaking his head.

“She does, though. The trouble is that sometimes she gets foolish ideas in her head and doesn't know what she's doing.” He nodded sagely. “And what's more, I love Daisy too. Once in a while I go off on a spree and make a fool of myself, but I always come back, and in my heart I love her all the time.”

“You're revolting,” said Daisy. She turned to me, and her voice, dropping an octave lower, filled the room with thrilling scorn: “Do you know why we left Chicago? I'm surprised that they didn't treat you to the story of that little spree.”

Gatsby walked over and stood beside her.

“Daisy, that's all over now,” he said earnestly. “It doesn't matter any more. Just tell him the truth – that you never loved him – and it's all wiped out forever.”

She looked at him blindly. “Why, – how could I love him – possibly?”

“You never loved him.”

She hesitated. Her eyes fell on Jordan and me with a sort of appeal, as though she realized at last what she was doing – and as though she had never, all along, intended doing anything at all. But it was done now. It was too late.

“I never loved him,” she said, with perceptible reluctance.

“Not that day I carried you down from the Punch Bowl to keep your shoes dry?” There was a husky tenderness in his tone. “…Daisy?”

“Please don't.” Her voice was cold, but the rancour was gone from it. She looked at Gatsby. “There, Jay,” she said – but her hand as she tried to light a cigarette was trembling. Suddenly she threw the cigarette and the burning match on the carpet.

“Oh, you want too much!” she cried to Gatsby. “I love you now – isn't that enough? I can't help what's past.” She began to sob helplessly. “I did love him once – but I loved you too.”

Gatsby's eyes opened and closed.

“You loved me TOO?” he repeated.

“Even that's a lie,” said Tom savagely. “She didn't know you were alive. Why, – there're things between Daisy and me that you'll never know, things that neither of us can ever forget.”

The words seemed to bite physically into Gatsby.

“I want to speak to Daisy alone,” he insisted. “She's all excited now – ”

“Even alone I can't say I never loved Tom,” she admitted in a pitiful voice. “It wouldn't be true.”

“Of course it wouldn't,” agreed Tom.

She turned to her husband.

“As if it mattered to you,” she said.

“Of course it matters. I'm going to take better care of you from now on.”

“You don't understand,” said Gatsby, with a touch of panic. “You're not going to take care of her any more.”

“I'm not?” Tom opened his eyes wide and laughed. He could afford to control himself now. “Why's that?”

“Daisy's leaving you.”

“Nonsense.”

“I am, though,” she said with a visible effort.

“She's not leaving me!” Tom's words suddenly leaned down over Gatsby.

“Certainly not for a common swindler who'd have to steal the ring he put on her finger.”

“I won't stand this!” cried Daisy. “Oh, please let's get out.”

“Who are you, anyhow?” broke out Tom. “I've made a little investigation into your affairs. I found out what your 'drug stores' were.” He turned to us and spoke rapidly. “He sold alcohol over the counter.”

“What about it[60], old sport?” said Gatsby politely.

“Don't you call me 'old sport'!” cried Tom.

I glanced at Daisy who was staring terrified between Gatsby and her husband and at Jordan who had begun to balance an invisible but absorbing object on the tip of her chin. Then I turned back to Gatsby – and was startled at his expression. He looked – and this is said in all contempt for the babbled slander of his garden – as if he had “killed a man.” For a moment the set of his face could be described in just that fantastic way.

It passed, and he began to talk excitedly to Daisy, denying everything, defending his name against accusations that had not been made. But with every word she was drawing further and further into herself, so he gave that up and only the dead dream fought on as the afternoon slipped away, trying to touch what was no longer tangible, struggling unhappily, undespairingly, toward that lost voice across the room.

The voice begged again to go.

“PLEASE, Tom! I can't stand this any more.”

Her frightened eyes told that whatever intentions, whatever courage she had had, were definitely gone.

“You two start on home, Daisy,” said Tom. “In Mr. Gatsby's car.”

She looked at Tom, alarmed now, but he insisted with magnanimous scorn.

“Go on. He won't annoy you. I think he realizes that his presumptuous little flirtation is over.”

They were gone, without a word, snapped out, made accidental, isolated, like ghosts even from our pity.

After a moment Tom got up and began wrapping the unopened bottle of whiskey in the towel.

“Want any of this stuff? Jordan?…Nick?”

I didn't answer.

“Nick?” He asked again.

“What?”

“Want any?”

“No… I just remembered that today's my birthday.”

I was thirty. Before me stretched the portentous menacing road of a new decade.

It was seven o'clock when we got into the coupe with him and started for Long Island. Tom talked incessantly, exulting and laughing, but his voice was as remote from Jordan and me as the foreign clamor on the sidewalk or the tumult of the elevated overhead. Human sympathy has its limits and we were content to let all their tragic arguments fade with the city lights behind. Thirty – the promise of a decade of loneliness, a thinning list of single men to know, a thinning brief-case of enthusiasm, thinning hair. But there was Jordan beside me who, unlike Daisy, was too wise ever to carry well-forgotten dreams from age to age. As we passed over the dark bridge her wan face fell lazily against my coat's shoulder and the formidable stroke of thirty died away with the reassuring pressure of her hand.

So we drove on toward death through the cooling twilight.

The young Greek Michaelis[61] was the principal witness at the inquest. He had slept through the heat until after five, when he went to the garage and found George Wilson sick in his office. Michaelis advised him to go to bed but Wilson refused. While his neighbour was trying to persuade him some noise broke out overhead.

“I've got my wife locked in up there[62],” explained Wilson calmly. “She's going to stay there till the day after tomorrow and then we're going to move away.”

Michaelis was astonished; they had been neighbours for four years and Wilson had never seemed capable of such a statement[63]. He was his wife's man and not his own.

So naturally Michaelis tried to find out what had happened, but Wilson wouldn't say a word. Michaelis took the opportunity to get away, intending to come back later. But he didn't.

A little after seven he was heard Mrs. Wilson's voice, loud and scolding, downstairs in the garage.

“Beat me!” he heard her cry. “Throw me down and beat me, you dirty little coward!”

A moment later she rushed out into the dusk, waving her hands and shouting; before he could move from his door the business was over[64].

The “death car” as the newspapers called it, didn't stop; it came out of the gathering darkness and then disappeared around the next bend. Michaelis wasn't even sure of its colour – somebody told the first policeman that it was yellow. Myrtle Wilson was lying dead. Her mouth was wide open.

We saw the three or four automobiles and the crowd when we were still some distance away.

“Wreck!” said Tom. “That's good. Wilson'll have a little business at last. We'll take a look, just a look.”

Then he saw Myrtle's body.

“What happened – that's what I want to know!”

“Auto hit her. Instantly killed. She ran out in a road. Son-of-a-bitch didn't even stop the car.”

“I know what kind of car it was!”

Tom drove slowly until we were beyond the bend. In a little while I saw that the tears were overflowing down his face.

“The coward!” he whimpered. “He didn't even stop his car.”

The Buchanans' house floated suddenly toward us through the dark trees. Tom stopped beside the porch.

I hadn't gone twenty yards when I heard my name and Gatsby stepped from between two bushes into the path.

“What are you doing?” I inquired.

“Just standing here, old sport. Did you see any trouble on the road?” he asked after a minute.

“Yes.”

He hesitated.

“Was she killed?”

“Yes.”

“I thought so; I told Daisy I thought so. I got to West Egg by a side road,” he went on, “and left the car in my garage. I don't think anybody saw us but of course I can't be sure. Who was the woman?” he inquired.

“Her name was Wilson. Her husband owns the garage. How did it happen? Was Daisy driving?”

“Yes,” he said after a moment, “but of course I'll say I was. You see, when we left New York she was very nervous – and this woman rushed out… It all happened in a minute but it seemed to me that she wanted to speak to us, thought we were somebody she knew.”