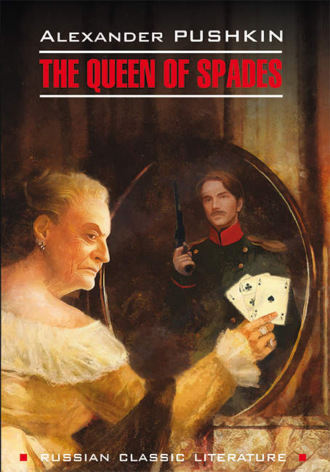

Александр Пушкин

Пиковая дама / The Queen of Spades

© КАРО, 2017

Все права защищены

The Queen Of Spades

Translated by H. Twitchell

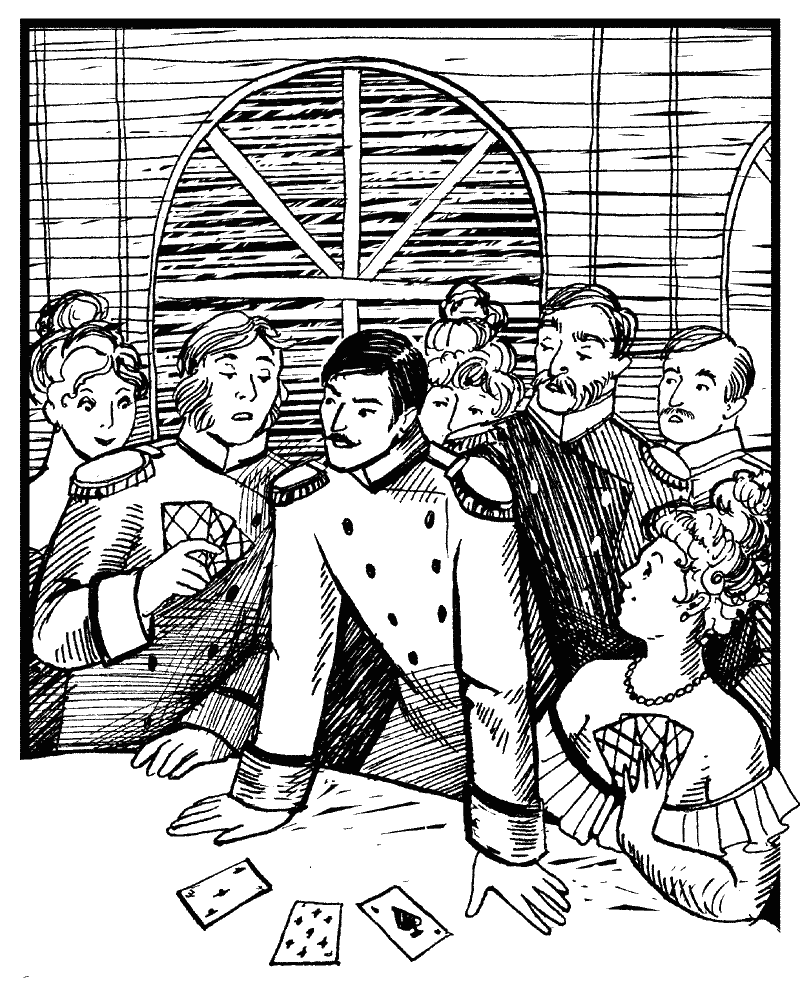

At the house of Naroumov, a cavalry officer, the long winter night had been passed in gambling. At five in the morning breakfast was served to the weary players. The winners ate with relish; the losers, on the contrary, pushed back their plates and sat brooding gloomily. Under the influence of the good wine, however, the conversation then became general.

“Well, Sourine?” said the host inquiringly.

“Oh, I lost as usual. My luck is abominable. No matter how cool I keep, I never win.”

“How is it, Herman, that you never touch a card?” remarked one of the men, addressing a young officer of the Engineering Corps. “Here you are with the rest of us at five o’clock in the morning, and you have neither played nor bet all night.”

“Play interests me greatly,” replied the person addressed, “but I hardly care to sacrifice the necessaries of life for uncertain superfluities.”

“Herman is a German, therefore economical; that explains it,” said Tomsky. “But the person I can’t quite understand is my grandmother, the Countess Anna Fedorovna.”

“Why?” inquired a chorus of voices.

“I can’t understand why my grandmother never gambles.”

“I don’t see anything very striking in the fact that a woman of eighty refuses to gamble,” objected Naroumov.

“Have you never heard her story?”

“No —”

“Well, then, listen to it. To begin with, sixty years ago my grandmother went to Paris, where she was all the fashion. People crowded each other in the streets to get a chance to see the ‘Muscovite Venus,’ as she was called. All the great ladies played faro, then. On one occasion, while playing with the Duke of Orleans, she lost an enormous sum. She told her husband of the debt, but he refused outright to pay it. Nothing could induce him to change his mind on the subject, and grandmother was at her wits’ ends. Finally, she remembered a friend of hers, Count Saint-Germain. You must have heard of him, as many wonderful stories have been told about him. He is said to have discovered the elixir of life, the philosopher’s stone, and many other equally marvelous things. He had money at his disposal, and my grandmother knew it. She sent him a note asking him to come to see her. He obeyed her summons and found her in great distress. She painted the cruelty of her husband in the darkest colors, and ended by telling the Count that she depended upon his friendship and generosity.

“‘I could lend you the money,’ replied the Count, after a moment of thoughtfulness, ‘but I know that you would not enjoy a moment’s rest until you had returned it; it would only add to your embarrassment. There is another way of freeing yourself.’

“‘But I have no money at all,’ insisted my grandmother.

“‘There is no need of money. Listen to me.’

“The Count then told her a secret which any of us would give a good deal to know.”

The young gamesters were all attention. Tomsky lit his pipe, took a few whiffs, then continued:

“The next evening, grandmother appeared at Versailles at the Queen’s gaming-table. The Duke of Orleans was the dealer. Grandmother made some excuse for not having brought any money, and began to punt. She chose three cards in succession, again and again, winning every time, and was soon out of debt.”

“A fable,” remarked Herman; “perhaps the cards were marked.”

“I hardly think so,” replied Tomsky, with an air of importance.

“So you have a grandmother who knows three winning cards, and you haven’t found out the magic secret.”

“I must say I have not. She had four sons, one of them being my father, all of whom are devoted to play; she never told the secret to one of them. But my uncle told me this much, on his word of honor. Tchaplitzky, who died in poverty after having squandered millions, lost at one time, at play, nearly three hundred thousand rubles. He was desperate and grandmother took pity on him. She told him the three cards, making him swear never to use them again. He returned to the game, staked fifty thousand rubles on each card, and came out ahead, after paying his debts.”

As day was dawning the party now broke up, each one draining his glass and taking his leave.

The Countess Anna Fedorovna was seated before her mirror in her dressing-room. Three women were assisting at her toilet. The old Countess no longer made the slightest pretensions to beauty, but she still clung to all the habits of her youth, and spent as much time at her toilet as she had done sixty years before. At the window a young girl, her ward, sat at her needlework.

“Good afternoon, grandmother,” cried a young officer, who had just entered the room. “I have come to ask a favor of you.”

“What, Pavel?”

“I want to be allowed to present one of my friends to you, and to take you to the ball on Tuesday night.”

“Take me to the ball and present him to me there.”

After a few more remarks the officer walked up to the window where Lisaveta Ivanovna sat.

“Whom do you wish to present?” asked the girl.

“Naroumov; do you know him?”

“No; is he a soldier?”

“Yes.”

“An engineer?”

“No; why do you ask?”

The girl smiled and made no reply.

Pavel Tomsky took his leave, and, left to herself, Lisaveta glanced out of the window. Soon, a young officer appeared at the corner of the street; the girl blushed and bent her head low over her canvas.

This appearance of the officer had become a daily occurrence. The man was totally unknown to her, and as she was not accustomed to coquetting with the soldiers she saw on the street, she hardly knew how to explain his presence. His persistence finally roused an interest entirely strange to her. One day, she even ventured to smile upon her admirer, for such he seemed to be.

The reader need hardly be told that the officer was no other than Herman, the would-be gambler, whose imagination had been strongly excited by the story told by Tomsky of the three magic cards.

“Ah,” he thought, “if the old Countess would only reveal the secret to me. Why not try to win her good-will and appeal to her sympathy?”

With this idea in mind, he took up his daily station before the house, watching the pretty face at the window, and trusting to fate to bring about the desired acquaintance.

One day, as Lisaveta was standing on the pavement about to enter the carriage after the Countess, she felt herself jostled and a note was thrust into her hand. Turning, she saw the young officer at her elbow. As quick as thought, she put the note in her glove and entered the carriage. On her return from the drive, she hastened to her chamber to read the missive, in a state of excitement mingled with fear. It was a tender and respectful declaration of affection, copied word for word from a German novel. Of this fact, Lisa was, of course, ignorant.

The young girl was much impressed by the missive, but she felt that the writer must not be encouraged. She therefore wrote a few lines of explanation and, at the first opportunity, dropped it, with the letter, out of the window. The officer hastily crossed the street, picked up the papers and entered a shop to read them.

In no wise daunted by this rebuff, he found the opportunity to send her another note in a few days. He received no reply, but, evidently understanding the female heart, he presevered, begging for an interview. He was rewarded at last by the following:

“To-night we go to the ambassador’s ball. We shall remain until two o’clock. I can arrange for a meeting in this way. After our departure, the servants will probably all go out, or go to sleep. At half-past eleven enter the vestibule boldly, and if you see any one, inquire for the Countess; if not, ascend the stairs, turn to the left and go on until you come to a door, which opens into her bedchamber. Enter this room and behind a screen you will find another door leading to a corridor; from this a spiral staircase leads to my sitting-room. I shall expect to find you there on my return.”

Herman trembled like a leaf as the appointed hour drew near. He obeyed instructions fully, and, as he met no one, he reached the old lady’s bedchamber without difficulty. Instead of going out of the small door behind the screen, however, he concealed himself in a closet to await the return of the old Countess.

The hours dragged slowly by; at last he heard the sound of wheels. Immediately lamps were lighted and servants began moving about. Finally the old woman tottered into the room, completely exhausted. Her women removed her wraps and proceeded to get her in readiness for the night. Herman watched the proceedings with a curiosity not unmingled with superstitious fear. When at last she was attired in cap and gown, the old woman looked less uncanny than when she wore her ball-dress of blue brocade.

She sat down in an easy chair beside a table, as she was in the habit of doing before retiring, and her women withdrew. As the old lady sat swaying to and fro, seemingly oblivious to her surroundings, Herman crept out of his hiding-place.

At the slight noise the old woman opened her eyes, and gazed at the intruder with a half-dazed expression.

“Have no fear, I beg of you,” said Herman, in a calm voice. “I have not come to harm you, but to ask a favor of you instead.”

The Countess looked at him in silence, seemingly without comprehending him. Herman thought she might be deaf, so he put his lips close to her ear and repeated his remark. The listener remained perfectly mute.

“You could make my fortune without its costing you anything,” pleaded the young man; “only tell me the three cards which are sure to win, and:”

Herman paused as the old woman opened her lips as if about to speak.

“It was only a jest; I swear to you, it was only a jest,” came from the withered lips.

“There was no jesting about it. Remember Tchaplitzky, who, thanks to you, was able to pay his debts.”

An expression of interior agitation passed over the face of the old woman; then she relapsed into her former apathy.

“Will you tell me the names of the magic cards, or not?” asked Herman after a pause.

There was no reply.

The young man then drew a pistol from his pocket, exclaiming: “You old witch, I’ll force you to tell me!”

At the sight of the weapon the Countess gave a second sign of life. She threw back her head and put out her hands as if to protect herself; then they dropped and she sat motionless.

Herman grasped her arm roughly, and was about to renew his threats, when he saw that she was dead!

* * *

Seated in her room, still in her ball-dress, Lisaveta gave herself up to her reflections. She had expected to find the young officer there, but she felt relieved to see that he was not.

Strangely enough, that very night at the ball, Tomsky had rallied her about her preference for the young officer, assuring her that he knew more than she supposed he did.

“Of whom are you speaking?” she had asked in alarm, fearing her adventure had been discovered.

“Of the remarkable man,” was the reply. “His name is Herman.”

Lisa made no reply.

“This Herman,” continued Tomsky, “is a romantic character; he has the profile of a Napoleon and the heart of a Mephistopheles. It is said he has at least three crimes on his conscience. But how pale you are.”

“It is only a slight headache. But why do you talk to me of this Herman?”

“Because I believe he has serious intentions concerning you.”

“Where has he seen me?”

“At church, perhaps, or on the street.”

The conversation was interrupted at this point, to the great regret of the young girl. The words of Tomsky made a deep impression upon her, and she realized how imprudently she had acted. She was thinking of all this and a great deal more when the door of her apartment suddenly opened, and Herman stood before her. She drew back at sight of him, trembling violently.

“Where have you been?” she asked in a frightened whisper.

“In the bedchamber of the Countess. She is dead,” was the calm reply.

“My God! What are you saying?” cried the girl.

“Furthermore, I believe that I was the cause of her death.”

The words of Tomsky flashed through Lisa’s mind.

Herman sat down and told her all. She listened with a feeling of terror and disgust. So those passionate letters, that audacious pursuit were not the result of tenderness and love. It was money that he desired. The poor girl felt that she had in a sense been an accomplice in the death of her benefactress. She began to weep bitterly. Herman regarded her in silence.

“You are a monster!” exclaimed Lisa, drying her eyes.

“I didn’t intend to kill her; the pistol was not even loaded.

“How are you going to get out of the house?” inquired Lisa. “It is nearly daylight. I intended to show you the way to a secret staircase, while the Countess was asleep, as we would have to cross her chamber. Now I am afraid to do so.”

“Direct me, and I will find the way alone,” replied Herman.

She gave him minute instructions and a key with which to open the street door. The young man pressed the cold, inert hand, then went out.

The death of the Countess had surprised no one, as it had long been expected. Her funeral was attended by every one of note in the vicinity. Herman mingled with the throng without attracting any especial attention. After all the friends had taken their last look at the dead face, the young man approached the bier. He prostrated himself on the cold floor, and remained motionless for a long time. He rose at last with a face almost as pale as that of the corpse itself, and went up the steps to look into the casket. As he looked down it seemed to him that the rigid face returned his glance mockingly, closing one eye. He turned abruptly away, made a false step, and fell to the floor. He was picked up, and, at the same moment, Lisaveta was carried out in a faint.

Herman did not recover his usual composure during the entire day. He dined alone at an out-of-the-way restaurant, and drank a great deal, in the hope of stifling his emotion. The wine only served to stimulate his imagination. He returned home and threw himself down on his bed without undressing.

During the night he awoke with a start; the moon shone into his chamber, making everything plainly visible. Some one looked in at the window, then quickly disappeared. He paid no attention to this, but soon he heard the vestibule door open. He thought it was his orderly, returning late, drunk as usual. The step was an unfamiliar one, and he heard the shuffling sound of loose slippers.

The door of his room opened, and a woman in white entered. She came close to the bed, and the terrified man recognized the Countess.

“I have come to you against my will,” she said abruptly; “but I was commanded to grant your request. The tray, seven, and ace in succession are the magic cards. Twenty-four hours must elapse between the use of each card, and after the three have been used you must never play again.”

The fantom then turned and walked away. Herman heard the outside door close, and again saw the form pass the window.

He rose and went out into the hall, where his orderly lay asleep on the floor. The door was closed. Finding no trace of a visitor, he returned to his room, lit his candle, and wrote down what he had just heard.

Two fixed ideas cannot exist in the brain at the same time any more than two bodies can occupy the same point in space. The tray, seven, and ace soon chased away the thoughts of the dead woman, and all other thoughts from the brain of the young officer. All his ideas merged into a single one: how to turn to advantage the secret paid for so dearly. He even thought of resigning his commission and going to Paris to force a fortune from conquered fate. Chance rescued him from his embarrassment.

* * *

Tchekalinsky, a man who had passed his whole life at cards, opened a club at St. Petersburg. His long experience secured for him the confidence of his companions, and his hospitality and genial humor conciliated society.

The gilded youth flocked around him, neglecting society, preferring the charms of faro to those of their sweethearts. Naroumov invited Herman to accompany him to the club, and the young man accepted the invitation only too willingly.

The two officers found the apartments full. Generals and statesmen played whist; young men lounged on sofas, eating ices or smoking. In the principal salon stood a long table, at which about twenty men sat playing faro, the host of the establishment being the banker.

He was a man of about sixty, gray-haired and respectable. His ruddy face shone with genial humor; his eyes sparkled and a constant smile hovered around his lips.

Naroumov presented Herman. The host gave him a cordial handshake, begged him not to stand upon ceremony, and returned, to his dealing. More than thirty cards were already on the table. Tchekalinsky paused after each coup, to allow the punters time to recognize their gains or losses, politely answering all questions and constantly smiling.

After the deal was over, the cards were shuffled and the game began again.

“Permit me to choose a card,” said Herman, stretching out his hand over the head of a portly gentleman, to reach a livret. The banker bowed without replying.

Herman chose a card, and wrote the amount of his stake upon it with a piece of chalk.

“How much is that?” asked the banker; “excuse me, sir, but I do not see well.”

“Forty thousand rubles,” said Herman coolly.

All eyes were instantly turned upon the speaker.

“He has lost his wits,” thought Naroumov.

“Allow me to observe,” said Tchekalinsky, with his eternal smile, “that your stake is excessive.”

“What of it?” replied Herman, nettled. “Do you accept it or not?”

The banker nodded in assent. “I have only to remind you that the cash will be necessary; of course your word is good, but in order to keep the confidence of my patrons, I prefer the ready money.”

Herman took a bank-check from his pocket and handed it to his host. The latter examined it attentively, then laid it on the card chosen.

He began dealing: to the right, a nine; to the left, a tray.

“The tray wins,” said Herman, showing the card he held:a tray.

A murmur ran through the crowd. Tchekalinsky frowned for a second only, then his smile returned. He took a roll of bank-bills from his pocket and counted out the required sum. Herman received it and at once left the table.

The next evening saw him at the place again. Every one eyed him curiously, and Tchekalinsky greeted him cordially.

He selected his card and placed upon it his fresh stake. The banker began dealing: to the right, a nine; to the left, a seven.

Herman then showed his card:a seven spot. The onlookers exclaimed, and the host was visibly disturbed. He counted out ninety-four-thousand rubles and passed them to Herman, who accepted them without showing the least surprise, and at once withdrew.

The following evening he went again. His appearance was the signal for the cessation of all occupation, every one being eager to watch the developments of events. He selected his card:an ace.

The dealing began: to the right, a queen; to the left, an ace.

“The ace wins,” remarked Herman, turning up his card without glancing at it.

“Your queen is killed,” remarked Tchekalinsky quietly.

Herman trembled; looking down, he saw, not the ace he had selected, but the queen of spades. He could scarcely believe his eyes. It seemed impossible that he could have made such a mistake. As he stared at the card it seemed to him that the queen winked one eye at him mockingly.

“The old woman!” he exclaimed involuntarily.

The croupier raked in the money while he looked on in stupid terror. When he left the table, all made way for him to pass; the cards were shuffled, and the gambling went on.

Herman became a lunatic. He was confined at the hospital at Oboukov, where he spoke to no one, but kept constantly murmuring in a monotonous tone: “The tray, seven, ace! The tray, seven, queen!”

The Daughter of the Commandant

Translated by Milne Home

Chapter I. Sergeant of the Guards

My father, Andréj Petróvitch Grineff, after serving in his youth under Count Münich[1], had retired in 17… with the rank of senior major. Since that time he had always lived on his estate in the district of Simbirsk, where he married Avdotia, the eldest daughter of a poor gentleman in the neighbourhood. Of the nine children born of this union I alone survived; all my brothers and sisters died young. I had been enrolled as sergeant in the Séménofsky regiment by favour of the major of the Guard, Prince Banojik, our near relation. I was supposed to be away on leave till my education was finished. At that time we were brought up in another manner than is usual now.

From five years old I was given over to the care of the huntsman, Savéliitch[2], who from his steadiness and sobriety was considered worthy of becoming my attendant. Thanks to his care, at twelve years old I could read and write, and was considered a good judge of the points of a greyhound. At this time, to complete my education, my father hired a Frenchman, M. Beaupré, who was imported from Moscow at the same time as the annual provision of wine and Provence oil. His arrival displeased Savéliitch very much.

“It seems to me, thank heaven,” murmured he, “the child was washed, combed, and fed. What was the good of spending money and hiring a ‘moussié,’ as if there were not enough servants in the house?”

Beaupré, in his native country, had been a hairdresser, then a soldier in Prussia, and then had come to Russia to be “outchitel,” without very well knowing the meaning of this word[3]. He was a good creature, but wonderfully absent and hare-brained. His greatest weakness was a love of the fair sex. Neither, as he said himself, was he averse to the bottle, that is, as we say in Russia, that his passion was drink. But, as in our house the wine only appeared at table, and then only in liqueur glasses, and as on these occasions it somehow never came to the turn of the “outchitel” to be served at all, my Beaupré soon accustomed himself to the Russian brandy, and ended by even preferring it to all the wines of his native country as much better for the stomach. We became great friends, and though, according to the contract, he had engaged himself to teach me French, German, and all the sciences, he liked better learning of me to chatter Russian indifferently. Each of us busied himself with our own affairs; our friendship was firm, and I did not wish for a better mentor. But Fate soon parted us, and it was through an event which I am going to relate.

The washerwoman, Polashka, a fat girl, pitted with small-pox, and the one-eyed cow-girl, Akoulka, came one fine day to my mother with such stories against the “moussié,” that she, who did not at all like these kind of jokes, in her turn complained to my father, who, a man of hasty temperament, instantly sent for that rascal of a Frenchman. He was answered humbly that the “moussié” was giving me a lesson. My father ran to my room. Beaupré was sleeping on his bed the sleep of the just. As for me, I was absorbed in a deeply interesting occupation. A map had been procured for me from Moscow, which hung against the wall without ever being used, and which had been tempting me for a long time from the size and strength of its paper. I had at last resolved to make a kite of it, and, taking advantage of Beaupré’s slumbers, I had set to work.

My father came in just at the very moment when I was tying a tail to the Cape of Good Hope.

At the sight of my geographical studies he boxed my ears sharply, sprang forward to Beaupré’s bed, and, awaking him without any consideration, he began to assail him with reproaches. In his trouble and confusion Beaupré vainly strove to rise; the poor “outchitel” was dead drunk. My father pulled him up by the collar of his coat, kicked him out of the room, and dismissed him the same day, to the inexpressible joy of Savéliitch.

Thus was my education finished.

I lived like a stay-at-home son (nédorossíl)[4], amusing myself by scaring the pigeons on the roofs, and playing leapfrog with the lads of the courtyard[5], till I was past the age of sixteen. But at this age my life underwent a great change.

One autumn day, my mother was making honey jam in her parlour, while, licking my lips, I was watching the operations, and occasionally tasting the boiling liquid. My father, seated by the window, had just opened the Court Almanack, which he received every year. He was very fond of this book; he never read it except with great attention, and it had the power of upsetting his temper very much. My mother, who knew all his whims and habits by heart, generally tried to keep the unlucky book hidden, so that sometimes whole months passed without the Court Almanack falling beneath his eye. On the other hand, when he did chance to find it, he never left it for hours together. He was now reading it, frequently shrugging his shoulders, and muttering, half aloud —

“General! He was sergeant in my company. Knight of the Orders of Russia! Was it so long ago that we —”

At last my father threw the Almanack away from him on the sofa, and remained deep in a brown study, which never betokened anything good.

“Avdotia Vassiliévna,”[6] said he, sharply addressing my mother, “how old is Petróusha[7]?”

“His seventeenth year has just begun,” replied my mother. “Petróusha was born the same year our Aunt Anastasia Garasimofna[8] lost an eye, and that – ”

“All right,” resumed my father; “it is time he should serve. ’tis time he should cease running in and out of the maids’ rooms and climbing into the dovecote.”

The thought of a coming separation made such an impression on my mother that she dropped her spoon into her saucepan, and her eyes filled with tears. As for me, it is difficult to express the joy which took possession of me. The idea of service was mingled in my mind with the liberty and pleasures offered by the town of Petersburg. I already saw myself officer of the Guard, which was, in my opinion, the height of human happiness.

My father neither liked to change his plans, nor to defer the execution of them. The day of my departure was at once fixed. The evening before my father told me that he was going to give me a letter for my future superior officer, and bid me bring him pen and paper.

“Don’t forget, Andréj Petróvitch,” said my mother, “to remember me to Prince Banojik; tell him I hope he will do all he can for my Petróusha.”

“What nonsense!” cried my father, frowning. “Why do you wish me to write to Prince Banojik?”

“But you have just told us you are good enough to write to Petróusha’s superior officer.”

“Well, what of that?”

“But Prince Banojik is Petróusha’s superior officer. You know very well he is on the roll of the Séménofsky regiment.”

“On the roll! What is it to me whether he be on the roll or no? Petróusha shall not go to Petersburg! What would he learn there? To spend money and commit follies. No, he shall serve with the army, he shall smell powder, he shall become a soldier and not an idler of the Guard, he shall wear out the straps of his knapsack. Where is his commission? Give it to me.”

My mother went to find my commission, which she kept in a box with my christening clothes, and gave it to my father with, a trembling hand. My father read it with attention, laid it before him on the table, and began his letter.

Curiosity pricked me.

“Where shall I be sent,” thought I, “if not to Petersburg?”

I never took my eyes off my father’s pen as it travelled slowly over the paper. At last he finished his letter, put it with my commission into the same cover, took off his spectacles, called me, and said:

“This letter is addressed to Andréj Karlovitch R., my old friend and comrade. You are to go to Orenburg[9] to serve under him.”

All my brilliant expectations and high hopes vanished. Instead of the gay and lively life of Petersburg, I was doomed to a dull life in a far and wild country. Military service, which a moment before I thought would be delightful, now seemed horrible to me. But there was nothing for it but resignation. On the morning of the following day a travelling kibitka stood before the hall door. There were packed in it a trunk and a box containing a tea service, and some napkins tied up full of rolls and little cakes, the last I should get of home pampering.

My parents gave me their blessing, and my father said to me:

“Good-bye, Petr’; serve faithfully he to whom you have sworn fidelity; obey your superiors; do not seek for favours; do not struggle after active service, but do not refuse it either, and remember the proverb, ’take care of your coat while it is new, and of your honour while it is young.’”

My mother tearfully begged me not to neglect my health, and bade Savéliitch take great care of the darling. I was dressed in a short “touloup”[10] of hareskin, and over it a thick pelisse of foxskin. I seated myself in the kibitka with Savéliitch, and started for my destination, crying bitterly.

I arrived at Simbirsk during the night, where I was to stay twenty-four hours, that Savéliitch might do sundry commissions entrusted to him. I remained at an inn, while Savéliitch went out to get what he wanted. Tired of looking out at the windows upon a dirty lane, I began wandering about the rooms of the inn. I went into the billiard room. I found there a tall gentleman, about forty years of age, with long, black moustachios, in a dressing-gown, a cue in his hand, and a pipe in his mouth. He was playing with the marker, who was to have a glass of brandy if he won, and, if he lost, was to crawl under the table on all fours. I stayed to watch them; the longer their games lasted, the more frequent became the all-fours performance, till at last the marker remained entirely under the table. The gentleman addressed to him some strong remarks, as a funeral sermon, and proposed that I should play a game with him. I replied that I did not know how to play billiards. Probably it seemed to him very odd. He looked at me with a sort of pity. Nevertheless, he continued talking to me. I learnt that his name was Iván Ivánovitch[11] Zourine, that he commanded a troop in the ::th Hussars, that he was recruiting just now at Simbirsk, and that he had established himself at the same inn as myself. Zourine asked me to lunch with him, soldier fashion, and, as we say, on what Heaven provides. I accepted with pleasure; we sat down to table; Zourine drank a great deal, and pressed me to drink, telling me I must get accustomed to the service. He told good stories, which made me roar with laughter, and we got up from table the best of friends. Then he proposed to teach me billiards.